Monster

A monster is often a type of grotesque creature, whose appearance frightens and whose powers of destruction threaten the human world's social or moral order.

A monster can also be like a human, but in folklore, they are commonly portrayed as the lowest class, as mutants, deformed, supernatural, and otherworldly.

Animal monsters are outside the moral order, but sometimes have their origin in some human violation of the moral law (e.g. in the Greek myth, Minos does not sacrifice to Poseidon the white bull which the god sent him, so as punishment Poseidon makes Minos' wife, Pasiphaë, fall in love with the bull. She copulates with the beast, and gives birth to the man with a bull's head, the Minotaur). Human monsters are those who by birth were never fully human (Medusa and her Gorgon sisters) or who through some supernatural or unnatural act lost their humanity (werewolves, Frankenstein's monster), and so who can no longer, or who never could, follow the moral law of human society.

Monsters pre-date written history, and the academic study of the particular cultural notions expressed in a society's ideas of monsters is known as monstrophy.[1]

Monsters have appeared in literature and in feature-length films. Well-known monsters in fiction include Count Dracula, Frankenstein's monster, werewolves, mummies, and zombies.

Etymology

Monster derives from the Latin monstrum, itself derived ultimately from the verb moneo ("to remind, warn, instruct, or foretell"), and denotes anything "strange or singular, contrary to the usual course of nature, by which the gods give notice of evil," "a strange, unnatural, hideous person, animal, or thing," or any "monstrous or unusual thing, circumstance, or adventure." [2]

Cultural heritage

In the words of Tina Marie Boyer, assistant professor of medieval German literature at Wake Forest University, "monsters do not emerge out of a cultural void; they have a literary and cultural heritage".[3]

In the religious context of ancient Greeks and Romans, monsters were seen as signs of "divine displeasure", and it was thought that birth defects were especially ominous, being "an unnatural event" or "a malfunctioning of nature".[4]

Monsters are not necessarily abominations however. The Roman historian Suetonius, for instance, describes a snake's absence of legs or a bird's ability to fly as monstrous, as both are "against nature".[5] Nonetheless, the negative connotations of the word quickly established themselves, and by the playwright and philosopher Seneca's time, the word had extended into its philosophical meaning, "a visual and horrific revelation of the truth".[6]

In spite of this, mythological monsters such as the Hydra and Medusa are not natural beings, but divine entities. This seems to be a holdover from Proto-Indo-European religion and other belief systems, in which the divisions between "spirit," "monster," and "god" were less evident.

Monsters in fiction

Prose fiction

The history of monsters in fiction is long, for example Grendel in the epic poem Beowulf is an archetypal monster, deformed, brutal, with enormous strength and raiding a human settlement nightly to slay and feed on his victims. The modern literary monster has its roots on examples such as the monster in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and the vampire in Bram Stoker's Dracula.

Monsters are a staple of fantasy fiction, horror fiction or science fiction (where the monsters are often extraterrestrial in nature). There is also a burgeoning subgenre of erotic fiction involving monsters, monster erotica.

Film

Pre–World War II monster films

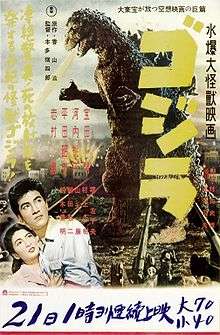

.jpg)

During the age of silent films, monsters tended to be human-sized, e.g. Frankenstein's monster, the Golem, werewolves and vampires. The film Siegfried featured a dragon that consisted of stop-motion animated models, as in RKO's King Kong, the first giant monster film of the sound era.

Universal Studios specialized in monsters, with Bela Lugosi's reprisal of his stage role, Dracula, and Boris Karloff playing Frankenstein's monster. The studio also made several lesser films, such as Man-Made Monster, starring Lon Chaney, Jr. as a carnival side-show worker who is turned into an electrically charged killer, able to dispatch victims merely by touching them, causing death by electrocution.

There was also a variant of Dr. Frankenstein, the mad surgeon Dr. Gogol (played by Peter Lorre), who transplanted hands that were reanimated with malevolent temperaments, in the film Mad Love.

Werewolves were introduced in films during this period, and similar creatures were presented in Cat People. Mummies were cinematically depicted as fearsome monsters as well. As for giant creatures, the cliffhanger of the first episode of the 1936 Flash Gordon serial did not use a costumed actor, instead using real-life lizards to depict a pair of battling dragons via use of camera perspective. However, the cliffhanger of the ninth episode of the same serial had a man in a rubber suit play the Fire Dragon, which picks up a doll representing Flash in its claws. The cinematic monster cycle eventually wore thin, having a comedic turn in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

Post–World War II monster films

In the post–World War II era, however, giant monsters returned to the screen with a vigor that has been causally linked to the development of nuclear weapons. One early example occurred in the American film The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, which was about a dinosaur that attacked a lighthouse. Subsequently, there were Japanese film depictions, (Godzilla, Gamera), British depictions (Gorgo), and even Danish depictions (Reptilicus), of giant monsters attacking cities. A recent depiction of a giant monster is depicted in J. J. Abrams's Cloverfield, which was released in theaters January 18, 2008. The intriguing proximity of other planets brought the notion of extraterrestrial monsters to the big screen, some of which were huge in size (such as King Ghidorah and Gigan), while others were of a more human scale. During this period, the fish-man monster Gill-man was developed in the film series Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Britain's Hammer Film Productions brought color to the monster movies in the late 1950s. Around this time, the earlier Universal films were usually shown on American television by independent stations (rather than network stations) by using announcers with strange personas, who gained legions of young fans. Although they have since changed considerably, movie monsters did not entirely disappear from the big screen as they did in the late 1940s.

Occasionally, monsters are depicted as friendly or misunderstood creatures. King Kong and Frankenstein's monster are two examples of misunderstood creatures. Frankenstein's monster is frequently depicted in this manner, in films such as Monster Squad and Van Helsing. The Hulk is an example of the "Monster as Hero" archetype. The theme of the "Friendly Monster" is pervasive in pop-culture. Chewbacca, Elmo, and Shrek are notable examples of friendly "monsters". The monster characters of Pixar's Monsters, Inc. franchise scare (and later entertain) children in order to create energy for running machinery in their home world, while the furry monsters of The Muppets and Sesame Street live in harmony with animals and humans alike. Japanese culture also commonly features monsters which are benevolent or likable, with the most famous examples being the Pokémon franchise and the pioneering anime My Neighbor Totoro. The book series/webisodes/toy line of Monster High is another example.

Games

Monsters are commonly encountered in fantasy or role-playing games and video games as enemies for players to fight against. They may include aliens, legendary creatures, extra-dimensional entities or mutated versions of regular animals.

Especially in role-playing games, "monster" is a catch-all term for hostile characters that are fought by the player. Sentient fictional races are usually not referred to as monsters. At other times, the term can carry a neutral connotation, such as in the Pokémon franchise, where it is used to refer to fictional creatures that resemble real-world animals. Characters in games may refer to all animals as "monsters".

See also

Monsters in legend

- Bakunawa

- Beast of Gévaudan

- Behemoth

- Bishop-fish

- Centaur

- Cerberus

- Changeling

- Charybdis

- Chimera

- Cryptozoology

- Cyclopes

- Demon

- Dragon

- Fearsome Critters

- Flying Spaghetti Monster

- Fouke Monster

- Freak

- Ghoul

- Goblin

- Gorgons

- Mythological hybrid

- Jiangshi

- Jinn

- Kaiju

- Kelpie

- Lake monster

- Legendary creature

- Hydra

- Leviathan

- Midgard Serpent

- Minokawa

- Minotaur

- Mummy

- Ogre

- Scylla

- Sea monster

- Swamp monster

- Tarasque

- Troll

- Vampire

- Warg

- Wendigo

- Werewolf

- Yaksha

- Yaoguai

- Yeti

- Yōkai

- Zombie

Monsters in fiction

- List of species in fantasy fiction

References

Notes

- Each card features a monster from Japanese mythology and a character from the hiragana syllabary.

Citations

- "Call for Papers for Preternature 2.2". Dr Leo Ruickbie. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- The Rev. J.E. Riddle, A Complete English-Latin and Latin-English Dictionary, London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1870, s.v. monstrum, Latin-English part, p. 399.

- Boyer, Tina Marie (2013). "The Anatomy of a Monster: The Case of Slender Man". Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural. 2 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beagon (2002), p. 127.

- Wardle (2006), p. 330.

- Staley (2010), pp. 80, 96, 109, 113 et passim.

Bibliography

- Asma, Stephen (2009). On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195336160.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beagon, Mary (2002). "Beyond Comparison: M. Sergius, Fortunae victor". In Clark, Gillian; Rajak, Tessa (eds.). Philosophy and Power in the Graeco-Roman World: Essays in Honour of Miriam Griffin. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829990-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Staley, Gregory A. (2010). Seneca and the Idea of Tragedy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538743-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wardle, David (2006). Cicero on Divination, Book 1. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Monster |