Mintaro, South Australia

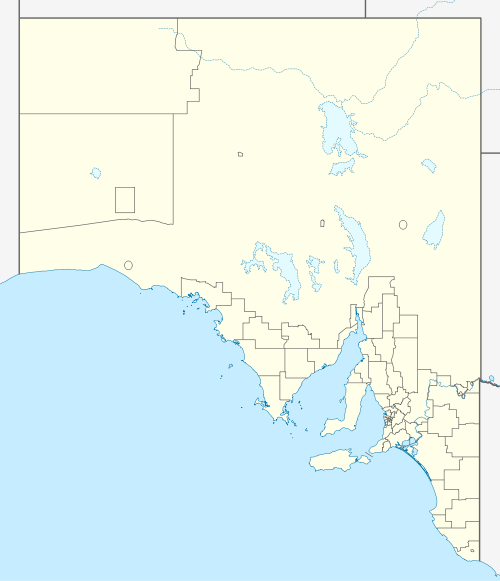

Mintaro is a historic town in the eastern Clare Valley, east of the Horrocks Highway, about 126 kilometres (78 miles) north of Adelaide, South Australia. The town lies at the south-eastern corner of the Hundred of Clare, within the Clare Valley wine region. Established in 1849, Mintaro is situated on land which was bought originally by Joseph and Henry Gilbert, which they sub-divided into 80 allotments.

| Mintaro South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Martindale Hall | |||||||||||||||

Mintaro | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°55′01″S 138°43′15″E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 188 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1849 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5415 | ||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | District Council of Clare and Gilbert Valleys | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Mid North | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Frome | ||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Grey | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Footnotes | [2] | ||||||||||||||

Mintaro was originally intended as a stopping and resting place for the bullock teams carting copper ore from the Burra mine to Port Wakefield. By 1876 the population was recorded as 400. Mintaro continued to develop as a rural service centre during the 1870s and early 1880s, when pastoral and agricultural activities boomed in the state's mid north. After 1930, there was a general decline in rural populations and little development took place within the town for several decades.

The Mintaro district includes prominent Martindale Hall and Kadlunga, two large pastoral properties. Known for its high quality, Mintaro slate is produced from what is believed to be the oldest continuing operating quarry in Australia. Although Mintaro is primarily an agricultural community, tourism plays an increasingly important role. Due to its historical and cultural significance, the entire town of Mintaro was declared a State Heritage Area for South Australia in 1984. In recent years, Mintaro has become a popular tourist destination and had increased building restoration and residential development.

Geography and climate

Mintaro is located in the eastern Clare Valley, about 126 km north of Adelaide, South Australia east of the Horrocks Highway.[3] The town lies at the south-eastern corner of the Hundred of Clare, in the undulating hills of South Australia's Mid North, within the Clare Valley wine region.[4] The region contains a series of valleys with altitudes ranging from 300m to over 500m above sea level, with an annual average of 9.3 sunlight hours per day.[5] The town is situated in a valley below Mount Horrocks at the crossroads of Jolly Way, Copper Ore Road, Min Man Road and Mintaro/Leasingham Roads. The main road in Mintaro is Burra Street.

Mintaro's climate is Mediterranean, with typically warm to hot summers and cool to cold moist winters.[6] Daily average temperatures range from 8.0 °C in winter to 21.4 °C in summer with an annual average rainfall of 632mm. Rainfall mostly occurs in winter and spring months (June - September).[6] There is occasional hail and although rare, snowfall has been recorded in the area.[6]

Flora and fauna

Prior to the European settlement of South Australia, the Clare Valley region consisted of grassy-woodlands and open grasslands providing an abundance of food for the Indigenous Ngadjuri people.[7][8] The most common native tree species in the region are Eucalyptus blue gum, E. peppermint gum, E. red stringybark and Casuarinaceae (commonly known as sheoak).[9] The Spring Gully Conservation Park is located about 15 km to the west of Mintaro.

History

The original inhabitants of the Clare Valley were the Indigenous Ngadjuri people, who spent thousands of years in the area before European settlement.[10][11] It is believed that they had major camping sites at Clare and Auburn, including the region now known as Mintaro.[12]

The Mintaro district was explored by Europeans in mid-1839, first by John Hill, and then by Edward John Eyre.[13] The area north of Gawler was officially opened by a series of special surveys in the early 1840s. Land in the Barossa and Clare Valleys was quickly taken up. The first settler in Mintaro was pastoralist James Stein who from 1841 held occupation licences for extensive sheep runs stretching from Mount Horrocks through Farrell Flat to the Burra district.[14] Stein subsequently established his homestead on a tributary of the Wakefield River, in a valley beneath Mount Horrocks, about three kilometres west of present Mintaro.[15]

With the discovery of copper at Kapunda in 1844, and then Burra in 1845, the area became attractive to both settlers and investors. In 1848 the Patent Copper Company established the 'Gulf Road' between the Burra Mine and Port Wakefield, along which bullock teams carried copper ore for shipment to Adelaide.[16] Between 1848 and 1851 several villages were established along the Gulf Road to take advantage of the trade generated by the bullock traffic. The towns were established about 9.0 miles (14.5 km) apart because that was the distance a bullock team could travel in a day.[3] Among the first of these towns was Mintaro.[17]

Mintaro is situated on land which was bought originally by Joseph and Henry Gilbert. They divided sections of the surrounding land into 80 allotments in 1849.[18] The village of Mintaro was originally intended as a stopping and resting place for the bullock teams (muleteers) carting the copper ore from the mine to the port, and returning with coal and supplies.[19] The first allotments surveyed and sold in Mintaro faced the Gulf Road (now Burra Street). As a result, Mintaro's early layout reflects the copper route, with streets aligned at 45 degrees to the north-south grid of the surveyed sections and government roads.[17]

The Magpie and Stump Hotel, at the entrance to the village, was first licensed (as the Mintaro Hotel) in December 1850, though it may have been operating earlier. The period from 1850-1860 was a prosperous one. A large proportion of the town's buildings date from this time and are located on the original subdivision.[19] Significant slate deposits were discovered in the early 1850s by a local farmer and the Mintaro Slate Quarry opened in 1854. By the early 1860s Mintaro slate was famous. By the early 1880s there were about 50 men employed at the quarries.[16]

The town's development was set back when the railway from Adelaide to Gawler was opened in 1857, and the copper teams were re-routed through Saddleworth and Riverton.[19] However, the slate quarries were being expanded at this time, and a flour mill was built in 1858. Mintaro developed as a service centre for the surrounding farming districts, which provided supplies for the mining townships at Kapunda and Burra. Over the next decade the population grew, and in 1866 the village expanded to an adjacent section.[20]

During the 1860s and 1870s public buildings appeared in the town, including a school, and a substantial number of Irish Catholics settled in and around Mintaro. In 1876 the population was recorded as 400.[20] The Burra mine closed in 1877, but Mintaro continued to develop as a rural service centre during the 1870s and early 1880s, when pastoral and agricultural activities boomed in the state's mid north.[16]

Mintaro railway station (renamed Merildin in 1918) was built in 1870 when the northern railway line was extended from Roseworthy to Burra.[16] It is situated about 7 kilometres east of the township. Mintaro was well placed to continue as an agricultural service centre despite the closure of the Burra mines. The surrounding farming districts of the fertile Gilbert Valley were able to reap the rewards of excellent wheat and wool prices during South Australia's rural boom of the 1870s and early 1880s.[19] This wealth was reflected in two large pastoral properties near Mintaro. Both Martindale Hall, built in 1879-80, and Kadlunga homestead, purchased in 1881 by Sir Samuel Way, reflected a way of life similar to that of English nobility. Mintaro, like rural village counterparts in England, provided these properties with a ready source of local labour.[16]

Live hare coursing was conducted from 1884 to 1986 (102 years) by the Mintaro Greyhound Coursing Club. Following passage of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 106 of 1985, live hare coursing stopped, but drag lure coursing continued until 1997, when it permanently ceased.[3]

The early 20th century, until the 1929 Depression, was a relatively prosperous period for the rural lower and mid north regions. After 1930, there was a general decline in rural populations. The continuing function of the slate quarry helped Mintaro survive, but little development took place within the town for several decades.[17]

Because of its rich natural and cultural heritage, Mintaro was designated as a State Heritage Area on 20 September 1984. The designation of a State Heritage Area is intended to ensure that changes to and development within the Mintaro area are managed in a way that the area's cultural significance is maintained. During the latter part of the 20th century some adaptation of historic buildings occurred to serve a growing demand in tourism and, in recent times, there has been increased residential development.[17]

Nomenclature

There are a range of theories around the naming of the township of Mintaro. Once thought to be of Spanish origin, Mintaro is now thought to be Aboriginal.[21]

In his 1892 booklet, Our Pastoral Industry, Sir F. W. Holder stated that the local Ngadjuri word "Mintadloo” may have over time degenerated or morphed into Mintaro.[18] This was given credence by pioneering Mid North pastoralist, Thomas Goode, who stated, "the blacks called the area 'mintadloo' but I don't know what it means."[22] Later, South Australian historian, Geoff Manning, citing anthropologist Norman Tindale's work, attributed the town's name to the local word mintinadlu (also rendered Mintadloo or Minta - Ngadlu) meaning 'netted water'.[22] This is thought to be a reference to the local Indigenous practice of using nets to trap emus, kangaroos and other creatures in the area for food.[3][12]

In contrast to Holder, Goode and Manning, according to a 1908 newspaper article, the name Mintaro is of Spanish origin, meaning 'camping place' or 'resting place'.[23] This was based on the fact that Spanish-speaking mule drivers (then known as muleteers) from Uruguay, Chile and Argentina transported copper ore from the Burra Mine to Port Wakefield in the mid-1850s. The muleteers used Mintaro as a resting place. The town's early history records show that as many as 100 Spanish-speaking mule drivers passed through and rested in the town each day.[3] Between 1853 and 1857 mule teams driven by muleteers were a common sight in the area.[24] However, with the exception of Río Mantaro (a long river running through the central region of Peru), there does not appear to be any words similar to Mintaro in the Spanish language.[18]

Whatever the true derivation of its name, the district was called Mintara in some of the earliest advertisements.[25] Born in 1849, cricketer Frederick Muir listed his birthplace as Mintara, Australia.[26] The Township of Mintaro name first appeared in an advertisement on 6 November 1849.[27] The town is pronounced "min-TAIR-oh" by the Clare Valley community.[28]

Slate and flagstones

Mintaro slate is produced from what is believed to be the oldest continuing operating quarry in Australia.[29][30] The slate was discovered in the early 1850s by a local farmer. In 1856 an English stonemason, Thompson Priest, leased the slate bearing area adjacent to the site of the original discovery and mining began in 1856.[31] Cornish Methodist miners were brought from England for this purpose.[19][31] The open-cut quarry is located about 1.5 km west of the township.

By 1860 Mintaro was South Australia's leading producer of high quality slate.[29] Mintaro slate was exhibited at the 1862 London International Exhibitions where it received the highest awards for large slab size and excellent flatness.[32] In 1910, the slate was described as some of the finest stone to be got in any part of the world.[33] Among its many uses and qualities, the perfectly flat slate surface makes it ideal for billiard and pool tables.[34] Walter Lindrum, the Australian billiard player who was the world champion from 1932 to 1950, praised the quality of Mintaro slate claiming it was equal to anything he had played on.[35] He later practiced at his Melbourne home on a table made from a single slab of slate from Mintaro.[3] Australian tennis player, Lleyton Hewitt, installed single slab three-quarter-sized tables also made from Mintaro Slate in his Adelaide house and Melbourne apartment.[36]

The slate was used initially as a local building material as well as in the construction of fermenting tanks at Clare Valley wineries, acid leaching tanks at the Kapunda copper mines, cricket pitches, water troughs, tombstones, fencing, switchboards and school blackboards.[32] Most of the heritage listed homes and ruins in Mintaro are built predominantly from locally mined slate.[37]

When Thompson Priest died in 1888, his quarry was acquired by a Melbourne firm. During the economic depression of the 1890s, the quarry languished for several years and wound down its production. In 1911 a local syndicate, the Mintaro Slate and Flagstone Company Limited, was formed and in 1912 an area of 60-80 acres adjacent to the quarry was purchased from Sir Samuel Way, together with the Melbourne agency which had been the distributor for Victoria.[31] With effective new management increased slate production began.[17] In 1981 the quarrying operations were again sold and reformed as the Mintaro Slate Quarries Pty Ltd, wholly owned in South Australia.[31]

The slate and flagstone deposits are part of the Mintaro Shale Formation within the Belair Subgroup. They were deposited on the sea floor during low energy conditions in the Adelaide Rift Complex about 800 million years ago.[38] They are grey, evenly bedded, finely laminated metasiltstones or slate with minor dolomitic siltstone. At Mintaro, the natural jointing and fracturing are widely spaced and facilitates the mining of large slabs.[36] Many prominent buildings in Adelaide feature Mintaro slate, including Parliament House, St Francis Xavier Cathedral, South Australian Museum, Supreme Court, Adelaide Town Hall, St Peters Cathedral and Mortlock Library.[29][36] Mintaro slate has been used in every Australian city and also in many regional areas.[32]

In recent time use of the slate has established a niche market that includes paving, kitchen and table tops, fireplaces, flooring, verandah edging and heritage surfaces. The slate remains well known internationally for its use in billiard tables.[39]

Martindale Hall

The heritage listed Martindale Hall is a Neoclassical and Georgian styled mansion, modelled on the Dalemain estate in England's Lake District.[40] The Hall is situated within 19 hectares (47 acres) of pastoral property and located about 2.5 km south of Mintaro. It was built for Edmund Bowman after he inherited the Martindale Estate from his father.[41] Completed in 1880, the mansion was built of freestone from the neighboring Manoora quarries.[42] Almost all the skilled tradesmen who worked on Martindale came from England who returned when the construction was completed.[43] The house and surrounding property was named after Martindale in Cumbria, which was close to the family's home town. The 32-room mansion cost £30,000 (about A$5.62 million today) to build.[44] Bowman, who was a well-known pastoralist in South Australia, used the property for sheep farming.[45]

In 1890, after several years of droughts and low wool prices, growing debt forced Bowman to put the Martindale homestead up for sale. It was bought by William Tennant Mortlock in 1892. Mortlock continued with sheep farming, developed the gardens and orchards and pursued his horse racing interests.[46] He was a supporter of racing, and bred Yudnappinna, which won the A.R.C. Grand National in 1911.[47] Mortlock sat in the State Parliament for several years representing the electoral district of Flinders.[48] Mortlock and his wife, Rosina Tennant, had six children although only two survived to adulthood.

When William Mortlock died in 1913 the family estate was inherited by his son, John Andrew Tennant Mortlock, who returned to South Australia to take control of the estate, which included Martindale Hall. He resided at the Hall and became a successful pastoralist and stud Merino breeder.[49] A keen traveller, Mortlock decorated and furnished the Hall with mementos from Africa and Asia. Most are still on display today and include a genuine 16th Century ceremonial Samurai suit.[50] An active member of St Peter's Anglican Church in Mintaro, Mortlock was also a keen yachtsman, an amateur film-maker and an orchid exhibitor.[51] Shortly after he was diagnosed with cancer, Mortlock married Dorothy Beech in December 1948.[52] Dying childless in March 1950, his wife became the heir to the Mortlock fortune. Preferring to live in Adelaide, Dorothy left after her husband's death and the mansion remained uninhabited and derelict for almost 30 years.[40] Upon her death in 1979, she bequeathed Martindale Hall and the surrounding estate to the University of Adelaide.[53] On 24 July 1980, it was listed as a state heritage place on the South Australian Heritage Register.[54]

In 1986, Martindale Hall and the surrounding estate was handed to the South Australian Government by the University. On 5 December 1991, the land on which the building is located was proclaimed as the Martindale Hall Conservation Park under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 for "the purpose of conserving the historic features of the land."[55] From 1991 to late 2014, the property was managed under lease as a tourism enterprise, offering heritage bed and breakfast accommodation, weddings, other functions and access to the grounds and Hall to day visitors.[56][57] From 2015 the property was managed by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, which in August 2015 received an unsolicited bid for the purchase or long-term lease of Martindale Hall, wanting to turn it into a five-star luxury resort.[58] However, the National Trust bid to stop private developers taking control of the Hall because they wanted the estate to remain in public hands and be accessible to everyone.[59]

The iconic and award-winning Australian film, Picnic at Hanging Rock, was partially filmed at Martindale Hall in 1975.[40] The Hall remains open to the public and attracts about 100,000 visitors annually.[60]

Kadlunga

The heritage listed, 2,367.73-hectare (5,850.8-acre) mixed-farming property of Kadlunga is located about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of Mintaro.[15][61] Kadlunga has been described as one of the most historic properties in the Mid North area.[61] The property has three rivers which pass through it—Broughton, Wakefield and Hutt—and has an annual average rainfall of 600–650 millimetres (24–26 in). It has 36 dams, 15 bores and wells, and two water licenses.[62]

The first European settler at Kadlunga was pastoralist James Stein who, from 1841, held occupation licences for extensive sheep runs stretching from Mount Horrocks through Farrell Flat to the Burra district. Stein established his homestead on a tributary to the Wakefield River, in a valley beneath Mount Horrocks, and named it Kadlunga, an Aboriginal word for 'sweet hills', after the abundant honeysuckle located there at the time.[63][64] However, the property was also known as Katalunga in its early period.[65] Stein built a two-storey homestead, completed in 1857, constructed of random coursed bluestone.[61]

Sir Samuel Way, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of South Australia purchased the property in 1881.[64] In following decades, Kadlunga Station became a famed sheep and horse stud. The first registered Percheron horses to arrive in Australia, in 1915, were sent to Kadlunga.[66] The property was successively owned by some prominent South Australians including John Chewings, Sir Samuel Way and Alexander Melrose.[61] The Gosse family (descendants of Melrose) owned the property for over 100 years before selling the estate in 2017.[15][67]

The original 1857 house was virtually rebuilt during the 1919-20 alterations for Alexander Melrose.[61] The existing bluestone was rendered during the extensions to match the colour of the new walls of locally quarried, roughly squared random-coursed sandstone, with brick quoins and surrounds to openings. The house now consists of fifteen rooms and all interior fittings date from the 1919-20 alterations. The verandah enclosed the two-storeyed section and the laundry and kitchen in the single-storey wing to the north, while the balcony almost encircles the first floor of the main body of the house.[68] Extensive farm dry stone walls were built by Italian prisoners of war during World War II.[69]

Due to intrinsic architectural significance and associated history with prominent South Australian Sir Samuel Way and other early pioneers, the historic stone buildings of the Kadlunga Estate were listed on the Register of the National Estate on 21 March 1978.[68]

Merildin

Merildin is a historic locality easterly adjacent to Mintaro and now part of the bounded locality of Mintaro. Mintaro Railway station on the northern line to Burra was built about 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) east of Mintaro in 1870. In 1918 it was renamed to Merildin station.[16] Merildin is considered to be the main catchment area of the upper Wakefield River. The name Merildin is derived from an Indigenous word meaning "stopping place".[70]

Present day

The Mintaro state heritage area is a rare South Australian example of a well-preserved, mid 19th century village.[29] Thirty-three specific sites within the Mintaro state heritage area are state heritage-listed.[71] It also provides tourist accommodation for visitors to the Clare Valley. Mintaro's main commercial centre and the majority of its significant 19th century buildings are located along Burra Street.[19] The town is relatively isolated with little surrounding development.[20]

The historic centre of Mintaro contains a predominance of early Victorian buildings and other sites that contribute to its character and designation as a state heritage area.[72] At one time, the town contained all the basic facilities needed to cater for its own population and for the surrounding area but today many of these buildings have been converted to guest accommodation. It has a number of bed and breakfast establishments and a hotel. There are two winery cellar doors in the town, galleries, eateries, a gift shop and a hedge maze.[73][74] Surrounded by vineyards and farms, Mintaro is still an agricultural community.[75]

A 100 megawatt solar farm, to be known as the Chaff Mill Solar Farm, was proposed in 2017 to be located on farmland about 3.5 km to the north-east of the town.[76]

Agriculture

Primarily an agricultural community, Mintaro is surrounded by mixed-use farmland and vineyards.[77] Both are a vital part of the region and South Australia's economy.[78] The main type of farming is pastoralism.[79] Seasonally, wheat and canola fields are a common sight in the Mintaro region.[80]

The Clare Valley is one of Australia's oldest wine-producing areas, with a wine-making history dating back over 150 years.[81] Celebrated for its Riesling, the region also produces many other wine styles, including Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz.[82] Today, there are more than 5,000 hectares under vine, and over 40 cellar door outlets.[81][83][84]

Demographics

The 2016 Australian census listed Mintaro's population at 188 (93 males and 95 females). There were no Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. The median age was 54 years and children (0 – 14 years) made up 14% of the population. 81.4% of people were born in Australia. The most common ancestries in Mintaro were English 38.7%, Australian 27.7%, German 10.6%, Irish 7.7% and Scottish 7.3%.[85]

Governance

Mintaro is governed at the council level by the District Council of Clare and Gilbert Valleys.[86] At state level, Mintaro lies within the electoral district of Frome and federally, the electoral division of Grey.[87] Any development in the town is subject to state heritage approval.[17] The peak local body is the Mintaro Progress Association. The association works in partnership with the Clare and Gilbert Valleys Council to ensure local concerns and issues are brought before the council.[88]

Sport

The MINMAN Sporting Club represents the affiliation of the Mintaro and Manoora Australian rules football and netball teams.[89] Known as the Eagles, the football club competes in the North Eastern Football League.[90] The netball club competes in the North Eastern Netball Association.[91] The club, football oval and netball courts are located in Mintaro at Mortlock Park on the corner of Leasingham and Jacka Roads.[92]

The Mintaro Bowling Club was established in 1959. There are men's, women's and social (the Night Owls) competitions.[89] The club and home games are played at Burra Street, adjacent to Torr Park on a natural grass surface. Also on Burra Street is the Mintaro Tennis Club with three synthetic grass courts.[93]

The Auburn-Mintaro Cricket Club represents the combined districts of Auburn and Mintaro.[89] Known as the Bullants, the club competes in the Stanley Cricket Association.[94] Home games are played at the Auburn recreational grounds on Saddleworth Road.

Tourism

Although Mintaro is primarily an agricultural community, in recent times tourism associated with the wine industry has played an increasingly important role. A number of heritage bed and breakfast establishments are located in the precinct to cater for accommodation demand.[95]

The best way to explore and see Mintaro is by foot. Self-guided walking tours around town to view the historic heritage-listed buildings and ruins can take up to two hours.[96] The Mintaro Garden Rooms are located on Kingston Road.[97] The award-winning garden (formerly known as Timandra Garden) is open to the public and popular for weddings, picnics and functions.[98]

The Clare Valley gourmet weekend commenced in 1984 and is held in May every year to celebrate the end of vintage.[99] The festival gives visitors an insight into the process of making wine as well as an opportunity to sample local cooking at over 30 wineries. Live music is played at some venues. The traditional living hedge maze is located on the corner of Jacka Road and Wakefield Street. Constructed in 1995, the maze is made from a network of over 800 conifer plants and is open most days except Tuesdays and public holidays.[74] The Mintaro Maze Bunny Hunt is held at Easter and the Haggis Hunt during the Clare Valley gourmet weekend.[100]

Located a short drive outside Mintaro off Jolly Way on Polish Hill Road, the Polish Hill River Church Museum was established in 1996. The museum was established by the South Australian Polish community to document and commemorate the contribution of Polish migrants to the development of South Australia.[101] The museum is open from 11 am to 4 pm on first Sunday of each month (except January).[102] Although not officially part of the Riesling Trail, Mintaro is a popular bicycling destination recommended by Bicycling Australia.[103] All three courses of the Gran Fondo style Clare Classic road cycling event run through Mintaro.[104]

Notable residents

| Image | Name | Association to Mintaro | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Edmund Bowman Jr (1855–1921) | Purchased Holm Hill at Mintaro, part of the Martindale estate and established a merino stud farm there. Built Martindale Hall in the late 1870s. | [105] |

|

William Brown (1868–1930) | Born in Mintaro on 29 March 1868. Professor of law, political thinker, academic and jurist. | [106] |

|

John Chewings (1819–1879) | Owned and resided at Kadlunga. Landowner and goods supplier to the region. | [107] |

| Peter Cloke (born 1951) | Played 28 games for Richmond Football Club in the early 1970s. Played 145 games for North Adelaide Football Club from 1975 to 1981. Finished runner-up in the 1979 Magarey Medal count. Lives in Mintaro. | [108][109] | |

|

Hugh Fraser (1837–1900) | Emigrated to South Australia in 1863 with four brothers and worked at the slate quarry in Mintaro for four years. Subsequently, moved to Adelaide where he won the seat of West Adelaide in 1878. | [110] |

| Percy Hutton (1876–1951) | Born in Mintaro on 2 October 1876. Played a single first-class cricket match for South Australia during the 1905–06 Sheffield Shield season scoring 30 runs. | [111] | |

|

Norman Jolly (1882–1954) | Born in Mintaro on 5 August 1882. In 1904, he was the first South Australian to be chosen for a Rhodes Scholarship. Was a noted cricketer and Australian rules football player. | [112] |

| Michael Kelly (1905–1967) | Born in Mintaro on 16 April 1905. A rheumatologist, he wrote extensively on a wide range of medical, political, historical, ethical and literary matters. Won the Geigy prize in 1958. | [113] | |

|

Charles Kimber (1826–1913) | Worked in Mintaro as a farmer for a time. Elected to the South Australian House of Assembly seat of Stanley in April 1887. | [114] |

|

Alexander Melrose (1889–1962) | Owned and resided at Kadlunga where he bred sheep, cattle and horses. Represented the Liberal Party in the House of Assembly seats of Burra Burra and Stanley. | [115] |

|

John Mortlock (1894–1950) | Born and lived in Mintaro. Owned Martindale Hall and surrounding estate where he was a successful stud Merino sheep breeder and pastoralist. | [116] |

|

William Mortlock (1858–1913) | Purchased Martindale Hall and surrounding estate in 1891 where he was a successful grazier. Was elected to the seat of Flinders in the South Australian House of Assembly at the 1896 election. | [117] |

| Frederick Muir (1849–1921) | Born in Mintaro in 1849. Played one first-class cricket match for Otago in 1872/73. The New Zealand connection is unclear. | [118] | |

| John Jackson Oakden (1818–1884) | A pastoralist and early business partner of James Stein. Oakden managed the Kadlunga property under occupational licences between 1841 until 1850. | [119] | |

|

James Stein (1804–1877) | Pioneering settler of the Mid North of South Australia and founder of the Kadlunga pastoralism estate. | [120] |

| Alfred (Jack) Tanner (1887–1955) | Livestock authority who specialised in beef cattle. Worked for the Weston family at Kadlunga early in his working career and later married their daughter, Jean Way Weston. | [121] | |

| James Torr (1816–1894) | Arrived in Australia from England in 1847, eventually settling in Mintaro. Landowner and farmer to the district. Managed the Devonshire Hotel in Mintaro for a while. Known for many years as one of the largest landowners in the colony. Uncle of William George Torr. | [122] | |

|

Samuel Way (1836–1916) | Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of South Australia. Purchased Kadlunga in 1881 and owned the estate for 35 years. | [123] |

|

Lawrence Weathers (1890–1918) | New Zealand-born Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross. When he was a child of seven his family came to South Australia and settled in the Mintaro district. After leaving school, Weathers moved to Adelaide. | [124] |

|

George Young (c. 1822–1869) | Emigrated to South Australia in 1847 and lived at Mintaro as a surveyor / land agent for several years. Represented the seat of Stanley in the South Australian House of Assembly from 1862 to 1865. | [125] |

Gallery

Magpie & Stump Hotel, Mintaro

Magpie & Stump Hotel, Mintaro- Mintaro Institute hall

- Mintaro Catholic Church

- Mintaro church

- An 1800s cottage in Burra Street

A renovated Mintaro heritage cottage

A renovated Mintaro heritage cottage

See also

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Mintaro (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Placename Details: Mintaro". Property Location Browser Report. Government of South Australia. 4 March 2010. SA0002678. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Mintaro Archived 11 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine (8 February 2004). The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Geology of the Clare Valley: Information sheet Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Department of Primary Industries and Resources SA. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- The Clare Valley Archived 16 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Robertson of Clare Wines. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Climate and Weather Archived 24 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Clare Valley Rocks. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- A simplified look at Australia's vegetation. Published by Australian National Botanic Gardens and Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Spring Gully Conservation Park. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Groundwater flow in the Clare Valley. Published by Department of Water Resources. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Ashmeade, Chelsea (September 26, 2016). Robert 'Alfie' Hannaford's 'woman and child' statue unveiled. Northern Argus. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Australia's Clare Valley. Wine Australia. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Noye, Robert J. (1980). CLARE – A District History. Hawthorndene, South Australia: Investigator Press. pp. 216–218.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Eyre, Edward John (1815–1901) Archived 10 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Tanner, Alfred John (Jack) (1887–1955) Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Burton, Lydia (6 April 2017). "Northern Territory producer sells cattle properties to buy prestigious mixed-farming country in South Australia". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- History Archived 12 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro South Australia. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources. Mintaro State Heritage Area: Guidelines for new development Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Mintaro Archived 30 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro Historical Society. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Mintaro State Heritage Area (2008). History of Mintaro. Published by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

- Mintaro State Heritage Area. History. Published by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources.

- Davies, Natham (October 11, 2013). The A-Z of the meanings of South Australia's town names. The Advertiser. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Mintaro". Manning Index of South Australian History: Place Names of South Australia. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "NOMENCLATURE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA". Evening Journal. XLII (11635). South Australia. 1 July 1908. p. 2. Retrieved 12 January 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Mintaro History Archived 12 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro Progress Association. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Township of Mintara Archived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine (10 November 1849). Trove: The Adelaide Observer, page 1. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "Frederick Muir". ESPN Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Township of Mintaro Archived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine (6 November 1849). Trove: The South Australian, page 3. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Welcome to Mintaro Archived 16 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Lonely Planet. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Mintaro state heritage area Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mintaro Slate, the oldest stone quarry in Australia Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Australian Stone Advisory Association Ltd. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mintaro Slate Official Site. Company History Archived 12 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Lollino, Giorgio et al. (2014, p. 215 & 216). Engineering Geology for Society and Territory - Volume 5 Archived 12 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. OCLC 965458976. ISBN 9783319090481

- Mintaro Slate Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (8 June 1910). Trove: The Northern Argus, page 14. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mintaro Slate Quarries. Billiard Table Tops Archived 12 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Walter Lindrum Praises Mintaro Slate Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (17 July 1931). Trove: The Northern Argus, page 5. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mintaro Slate and Flagstone Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Clare Valley.com.au Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. Clare and Gilbert Valleys Council Development Plan (10 November 2016), page 37.

- Geology of the Clare Valley Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. South Australia Earth Resources Information Sheet. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mintaro Slate Quarries Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Puddy, Rebecca (20 June 2016). Miranda returns to joint fight for Picnic at Hanging Rock hall. The Australian. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Obituaries Australia. Bowman, Edmund (1855–1921) Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Mr E. Bowman's Mansion at Martindale Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (18 December 1880). Trove: Adelaide Evening Journal, page 2. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Martindale Hall Archived 4 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. South Australian History. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Martindale Hall Historic Museum. Martindale Hall Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Death of Well Known Pastoralist - The Late Mr Edmund Bowman Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (23 August 1921). Trove: The Adelaide Journal, page 1. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Mortlock, William Ranson (1821–1884) Archived 23 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Obituaries Australia. Mortlock, William Tennant (1858–1913) Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Mr William Mortlock Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Parliament of South Australia. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Death of Mr J. T. Mortlock Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (16 March 1950). Trove: Port Lincoln Times, page 1. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Martindale Hall. Clare Valley Wine, Food & Tourism Centre. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Death of Mr J. T. Mortlock Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (22 March 1950). Trove: Northern Argus, page 4. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Mortlock, Dorothy Elizabeth (1906–1979) Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Benefactors and donated collections: Mortlock. State Library of South Australia Archived 28 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ""Martindale Hall", Martindale Hall Conservation Park". South Australian Heritage Register. Government of South Australia. 24 July 1980. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE ACT 1972 SECTION 30(1): CONSTITUTION OF MARTINDALE HALL CONSERVATION PARK" (PDF). South Australian Government Gazette. Government of South Australia. 5 December 1991. p. 1668. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Clare Valley icon Martindale Hall to close and may be sold (31 October 2014). The Advertiser. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Caretakers re-focus on the collection at Martindale Hall Archived 13 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (23 January 2015). Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Martindale Hall: Bid to keep historic SA site in public hands Archived 21 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine (15 May 2016). ABC News. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Martindale Hall. National Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Martindale Hall Archived 17 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. National Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Bowden, Tom (31 March 2017). "Kadlunga: Historic Clare property bought by Northern Territory cattle farmer Tim Edmunds".

- Ashmeade, Chelsea (9 February 2016). "Kadlunga is put on the market". Stock Journal.

- Manning, Geoffrey. "Place Names of South Australia: Kadlunga". Manning Index of South Australia. State Library of South Australia. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Placename details: Kadlunga". Property Location Browser. Government of South Australia. 31 August 2009. SA0033438.

Feature Type: Homestead; MGA 94 Coordinates: 500000, 6016052 (Easting, Northing - Metres); GDA 94 Coordinates: -36, 135 (Latitude, Longitude - Decimal Degrees); Zone: 53; Named By: ; Date Named: ; Derivation of Name: Abna meaning Honeysuckle Hills; Other Details: Name of the property owned by Sir Samuel Way. No location established.

- The September Show Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (14 September 1889). Trove: South Australian Chronicle, page 22. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- History of the Breed Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Percheron Horse Breeders of Australia Inc. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Jock Gosse". Fox Real Estate. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

Jock's involvement in agriculture stems from a strong family history working on the land. Their property 'Kadlunga' had been in the family for over 100 years, successfully running 8,000 Merino sheep and 250 Charolais cattle.

- Department of the Environment and Energy. Australian Heritage Database. Search result for Kadlunga. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- South Australia shows off some stone walls Archived 31 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Flag Stone; Issue No 35, January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "Placename Details: Merildin". Property Location Browser. Government of South Australia. 31 October 2008. SA0026477.

- Department of the Environment and Energy. Australian Heritage Database. Search result for Mintaro. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Mintaro State Heritage Area. Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "Mintaro South Australia". Mintaro Progress Association. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mintaro Maze Archived 14 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Clare Valley Wine, Food & Tourism Centre. Mintaro Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Mintaro farmers raise solar farm worries (November 23, 2017). Plains Producer. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ‘Redesigning’ the modern Merino at Mintaro. Farming Ahead, number 269 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Mintaro S.A. Australia for Everyone. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Varied flowering times help spread frost risk. Stock Journal; 21 April 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Clare Valley Vineyards. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Wines of brilliance and innovation. Wine Australia. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Reillys Wines. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Mintaro Wines. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- 2016 Census QuickStats: Mintaro Archived 21 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Clare & Gilbert Valleys Council. Community Information. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Profile of the electoral division of Wakefield (SA). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Progress Association Archived 22 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro Progress Association. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- MINMAN Eagles Archived 20 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro South Australia. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- North Eastern Football League Archived 20 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Australian Rules Football.com.au. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- North Eastern Netball Association Archived 20 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Netball South Australia. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Clare & Gilbert Valley Council. Other Sporting Facilities. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Mintaro Tennis Club Archived 20 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Sports Courts International. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Auburn Mintaro Cricket Club Archived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. South Australia Cricket. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Accommodation Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro, South Australia. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Mintaro Heritage Walk. Walking SA. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Attractions Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro, South Australia. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Awards Archived 24 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Timandra Design & Landscaping. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Clare Valley Gourmet Weekend Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Clare Valley Wine, Food & Tourism Centre. Retrieved 2018-01-1-24.

- Mintaro Maze Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Clare Valley Wine, Food & Tourism Centre. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Polish Hill River Church Museum Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. South Australian Community History. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Mintaro Short Drives Archived 28 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Mintaro, South Australia. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Bicycling Australia. Clare Classic: Ten things to see and do in the Clare Valley. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Clare Classic. Course Overview. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Bowman, Edmund (1855–1921). Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 2018-01-25

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Brown, William Jethro (1868–1930). Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- S.A. Northern Pioneers: J. Chewings. State Library of South Australia. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- Peter Cloke Biography. Australian Football.com. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- SA Weekender. Mintaro (12 August 2018). Retrieved 5 January 2018

- Concerning People (12 May 1900). Trove: South Australian Register, page 4. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- First-class matches played by William Hutton (1) – CricketArchive. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Jolly, Norman William (1882–1954). Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Kelly, Michael (1905–1967). Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- Mr Charles Kimber (4 October 1902). Trove: Adelaide Observer, p. 22. Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- Approaching Elections (20 January 1933). Trove: Northern Argus, page 3. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Mortlock, John Andrew Tennant (1894–1950). Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Mortlock, William Ranson (1821–1884). Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- Frederick Muir. ESPN Cricket Info. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- Register, 10 March 1849, p. 2, and South Australian, 13 March 1849, p. 4.

- Pastoral Pioneers of South Australia, Vol 1. page 191.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Tanner, Alfred John (Jack) (1887–1955). Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- The late Mr James Torr of Mintaro (21 November 1894). Trove: South Australian Register, page 7. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography. Way, Sir Samuel James (1836–1916). Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- War Items. More Australian V.C.'s. Late Lance Corporal L. C. Weathers (10 January 1919). Trove: Southern Cross, page 19. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- Mr George Young Archived 20 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Parliament of South Australia: Former Members. Retrieved 2018-01-25.