Edward John Eyre

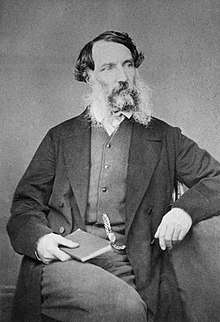

Edward John Eyre (5 August 1815 – 30 November 1901) was an English land explorer of the Australian continent, colonial administrator, and a controversial Governor of Jamaica.

Edward John Eyre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor of Jamaica | |

| In office 1862–1865 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Charles Henry Darling |

| Succeeded by | Henry Knight Storks |

| Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster, New Zealand | |

| In office 1848–1853 | |

| Governor | George Grey |

| Preceded by | None, position established |

| Succeeded by | None, position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 August 1815 Whipsnade, England, UK |

| Died | 30 November 1901 (aged 86) Devon, England, UK |

| Occupation | Explorer of Australia, Colonial Administrator, Grazier |

Early life

Eyre was born in Whipsnade, Bedfordshire, shortly before his family moved to Hornsea, Yorkshire, where he was christened.[1] His parents were Rev. Anthony William Eyre and Sarah (née Mapleton).[2] After completing grammar school at Louth and Sedbergh, he moved to Sydney rather than join the army or go to university. He gained experience in the new land by boarding with and forming friendships with prominent gentlemen and became a flock owner when he bought 400 lambs a month before his 18th birthday.[3]

In South Australia

In December 1837, Eyre started droving 1,000 sheep and 600 cattle overland from Monaro, New South Wales, to Adelaide, South Australia. Eyre, with his livestock and eight stockmen, arrived in Adelaide in July 1838.[4] In Adelaide, Eyre sold the livestock for a large profit.

With the money from the sale, Eyre set out to explore the interior of South Australia. In 1839, Eyre went on two separate expeditions: north to the Flinders Ranges and west to beyond Ceduna. The northern-most point of the first expedition was Mount Eyre; it was named by Governor Gawler on 11 July 1839.[5] In 1840, Eyre went on a third expedition, reaching a lake that was later named Lake Eyre, in his honor.

Overland to Albany

Eyre, together with his Aboriginal companion Wylie, was the first European to traverse the coastline of the Great Australian Bight and the Nullarbor Plain by land in 1840–1841, on an almost 2000 mile trip to Albany, Western Australia. He had originally led the expedition with John Baxter and three aborigines.

On 29 April 1841, two of the aborigines killed Baxter and left with most of the supplies. Eyre and Wylie were only able to survive because they chanced to encounter, at a bay near Esperance, Western Australia, a French whaling ship Mississippi, under the command of an Englishman, Captain Thomas Rossiter, for whom Eyre named the location Rossiter Bay. In 1845 he returned to England and published a narrative of his travels.[6]

Colonial Governor

From 1848 to 1853, he served as Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster Province in New Zealand under Sir George Grey.[7] He married Miss Adelaide Ormond in 1850. She was the sister of the politician John Davies Ormond.

Colonial Governor in Jamaica

From 1854 Eyre was Governor of several Caribbean island colonies, including Saint Vincent and Antigua.[8]

As Governor of Jamaica, Eyre, fearful of an island wide uprising, brutally suppressed the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865, which was sparked when Baptist preacher and rebel leader (and future National Hero of Jamaica) Paul Bogle encouraged and led a rebellion, and occasioned the death of 18 militia or officials. Up to 439 black peasants were killed in the reprisals, some 600 flogged and about 1000 houses burnt down. General Luke Smythe O'Connor was directly responsible for those who inflicted excessive punishment.[9] Eyre also authorised the execution of George William Gordon, a mixed-race colonial member of the Assembly who, though not actually involved in the rebellion, was tried for high treason by Lieutenant Herbert Brand in a court-martial. Gordon was openly critical of the Eyre regime in his capacity as an elected member of the Jamaican Assembly, but Eyre was convinced that Gordon was one of the leaders of the Morant Bay Rebellion. On 23 October, Gordon was hanged two days after his hastily-arranged trial, and Bogle followed him on to the gallows two days later, when he was hanged along with 14 others.[10]

The controlling European element of the Jamaican population—those who had most to lose—regarded Eyre as the hero who had saved Jamaica from disaster.[9] Eyre's influence on the white planters was so strong that he was able to convince the House of Assembly to pass constitutional reforms that brought the old form of government to an end and allowed Jamaica to become a Crown Colony, with an appointed (rather than an elected) legislature, on the basis that stronger legislative control would ward off another act of rebellion. This move ended the growing influence of the elected free people of colour Eyre distrusted, such as Gordon, Edward Jordon, and Robert Osborn. Before dissolving itself, the legislature passed legislation to deal with the recent emergency, including an Act that sanctioned martial law and – all-importantly for the litigation in Phillips v Eyre – an Act of Indemnity covering all acts done in good faith to suppress the rebellion after the proclamation of martial law.[9]

These events created great controversy in Britain, resulting in demands for Eyre to be arrested and tried for murdering Gordon. John Stuart Mill organised the Jamaica Committee, which demanded his prosecution and included some well-known British liberal intellectuals such as John Bright, Charles Darwin, Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes, Thomas Henry Huxley, Herbert Spencer and A. V. Dicey.[9] Other notable members of the committee included Charles Buxton, Edmond Beales, Leslie Stephen, James Fitzjames Stephen, Edward Frankland, Thomas Hill Green, Frederick Chesson, Goldwin Smith, Charles Lyell and Henry Fawcett.

The Governor Eyre Defence and Aid Committee was set up by Thomas Carlyle in September 1866 to argue that Eyre had acted decisively to restore order. The committee secretary was Hamilton Hume, a member of the Royal Geographical Society with whom Eyre had explored in New South Wales. His supporters included John Ruskin, Charles Kingsley, Charles Dickens, Lord Cardigan, Alfred Tennyson and John Tyndall.[9][11]

Cases against Lieutenant Brand and Brigadier Alexander Nelson (British Army officer) were presented to the Central Criminal Court but the grand jury declined to certify either case. Eyre resided in Market Drayton in Shropshire, which was outwith the jurisdiction of the court, so the indictment failed on that count. Barrister James Fitzjames Stephen travelled to Market Drayton but failed to convince the Justices to endorse his case against Eyre. The Jamaica Committee next asked the Attorney-General to certify the criminal information against Eyre but was rebuffed. Eyre then moved to London so that he might bring matters to a head and offer himself up to justice. The magistrate at Bow Street Police Court declined to arrest him, due to the failure of the cases against the soldiers, whereupon the imagined prosecutors applied to the Queen's Bench for a writ of mandamus justified by the Criminal Jurisdiction Act 1802 and succeeded. The Queen's Bench grand jury, upon presentation of the case against Eyre, declined to find a true bill of indictment, and Eyre was freed of criminal pursuit.[9]

The case went next to the civil courts. Alexander Phillips charged Eyre with six counts of assault and false imprisonment, in addition to conversion of Phillips's "goods and chattels",[9] and the case was eventually brought to the UK Court of Exchequer as Phillips v Eyre (1870) LR 6 QB 1, Exchequer Chamber. The case was influential in setting a precedent in English and Australian law over the conflict of laws, and choice of law to be applied in international torts cases.[12] Eyre was exonerated in the Queen's Bench, a writ of error was submitted to the Exchequer, whose judgment affirmed the one below, and an important precedent was thus set by Willes J.[9]

Later life

Eyre's legal expenses were covered by the British government in 1872, and in 1874 he was granted the pension of a retired colonial governor. He lived out the remainder of his life at Walreddon Manor in the parish of Whitchurch near Tavistock, Devon, where he died on 30 November 1901. He is buried in the Whitchurch churchyard.[2]

Recognition and legacy

A statue of Eyre is in Victoria Square in Adelaide as well as Rumbalara Reserve in Springfield NSW on the Mouat Walk. In 1970, an Australia Post (then Postmaster-General's Department) postage stamp bore his portrait.[13]

South Australia's Lake Eyre, Eyre Peninsula, Eyre Creek, Eyre Highway (the main highway from South Australia to Western Australia), Edward John Eyre High School, the Eyre Hotel in Whyalla, and the electoral district of Eyre in Western Australia, are named in his honour. So too are the villages of Eyreton and West Eyreton, and Eyrewell Forest, in Canterbury and the Eyre Mountains and Eyre Creek in Southland, New Zealand.

Eyre Road, Linton, Palmerston North also thought to be named after him as well as a few streets in Canterbury, New Zealand.

In 1971, the Australian composer Barry Conyngham wrote the opera Edward John Eyre, using poems by Meredith Oakes and extracts from Eyre's Journals of Expeditions of Discovery.[14]

See also

References

- Steve Pocock (2000). "History". Great Australian Bight Safaris. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2006.

- Geoffrey Dutton (1966), "Eyre, Edward John (1815–1901)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1 (Australian National University), accessed 25 October 2018.

- Kevin Koepplinger. "Hero and Tyrant:Edward John Eyre's Legacy". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 15 December 2012.

- Foster R., Nettelbeck A. (2011), Out of the Silence, p. 32-33 (Wakefield Press).

- Manning, Geoffrey H. (2012). "Names - E" (PDF). A Compendium of the Place Names of South Australia. State Library of South Australia. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

-

- Michael Wordsworth Standish (1966). "Eyre, Edward John". The 1966 Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Te Ara. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Peter Handford (2008). "Edward John Eyre and the Conflict of Laws". Melbourne University Law Review. 32 (3): 822–860.

- Gad Heuman, The Killing Time: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994).

- Thomas, Donald (1974), Charge! Hurrah! Hurrah! : a life of Cardigan of Balaclava, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 318–320, ISBN 0-7100-7914-1

- Geoffrey Dutton (1982) In search of Edward John Eyre South Melbourne: Macmillan. pp. 115–42. ISBN 0-333-33841-3

- Australian postage stamp honouring Edward John Eyre. australianstamp.com

- Radic, Thérèse (2002) [1 December 1992]. "Edward John Eyre". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- "Eyre, Edward John (1815–1901)", Dictionary of Australian Biography (Angus and Robertson, 1949).

- "Papers Relative to the Affairs of South Australia—Aborigines", Accounts and Papers 1843, Volume 3 (London: William Clowes and Sons), pp. 267–310.

- Geoffrey Dutton (1967), The Hero as Murderer: the life of Edward John Eyre, Australian explorer and Governor of Jamaica 1815–1901. Sydney: Collins ; Melbourne: Cheshire, (paperback reprint: Penguin, 1977).

- Julie Evans (2002), "Re-reading Edward Eyre—Race, resistance and repression in Australia and The Caribbean", Australian Historical Studies, 33: 175–198; doi:10.1080/10314610208596190.

- Catherine Hall (2002), Civilising Subjects: Colony and Metropoloe in the English Imagination, 1830–1867. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ivan Rudolph (2013), Eyre, the forgotten explorer. Sydney: HarperCollins.

- Journals of Expeditions of Discovery into Central Australia, and overland from Adelaide to King George's Sound, in the years 1840-41, sent by the Colonists of Australia, with the sanction and support of the Government; including an Account of the Manners and Customs of the Aborigines, and the state of their relations with Europeans. By E. J. Eyre, Resident Magistrate, Murray River. 2 volumes. London (1845). Available at the Internet Archive: Volume I, Volume II.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edward John Eyre |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward John Eyre. |

- Short biography

- Eyre's Journals from his 1840/1 expedition

- Works by Edward John Eyre at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward John Eyre at Internet Archive

- Biography in 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Richard Graves MacDonnell |

Lieutenant Governor of Saint Vincent 1854–1861 |

Succeeded by Anthony Musgrave |

| Preceded by Charles Henry Darling |

Governor of Jamaica 1862–1864 (acting); 1864–1865 |

Succeeded by Sir Henry Knight Storks |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by John Murray |

Clarke Medal 1901 |

Succeeded by Frederick Manson Bailey |