Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( /ˈkæm.bri.ən, ˈkeɪm-/ KAM-bree-ən, KAYM-) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon.[2] The Cambrian lasted 55.6 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 541 million years ago (mya) to the beginning of the Ordovician Period 485.4 mya.[3] Its subdivisions, and its base, are somewhat in flux. The period was established (as “Cambrian series”) by Adam Sedgwick,[2] who named it after Cambria, the Latin name of Wales, where Britain's Cambrian rocks are best exposed.[4][5][6] The Cambrian is unique in its unusually high proportion of lagerstätte sedimentary deposits, sites of exceptional preservation where "soft" parts of organisms are preserved as well as their more resistant shells. As a result, our understanding of the Cambrian biology surpasses that of some later periods.[7]

| Cambrian Period 541–485.4 million years ago | |

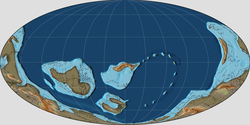

A map of the world as it appeared during the Stage 2 epoch of the mid-Cambrian. (520 ma) | |

| Mean atmospheric O 2 content over period duration |

c. 12.5 vol % (63 % of modern level) |

| Mean atmospheric CO 2 content over period duration |

c. 4500 ppm (16 times pre-industrial level) |

| Mean surface temperature over period duration | c. 21 °C (7 °C above modern level) |

| Sea level (above present day) | Rising steadily from 4m to 90m[1] |

The Cambrian marked a profound change in life on Earth; prior to the Cambrian, the majority of living organisms on the whole were small, unicellular and simple; the Precambrian Charnia being exceptional. Complex, multicellular organisms gradually became more common in the millions of years immediately preceding the Cambrian, but it was not until this period that mineralized—hence readily fossilized—organisms became common.[8] The rapid diversification of life forms in the Cambrian, known as the Cambrian explosion, produced the first representatives of all modern animal phyla. Phylogenetic analysis has supported the view that during the Cambrian radiation, metazoa (animals) evolved monophyletically from a single common ancestor: flagellated colonial protists similar to modern choanoflagellates.

Although diverse life forms prospered in the oceans, the land is thought to have been comparatively barren—with nothing more complex than a microbial soil crust[9] and a few molluscs that emerged to browse on the microbial biofilm.[10] Most of the continents were probably dry and rocky due to a lack of vegetation. Shallow seas flanked the margins of several continents created during the breakup of the supercontinent Pannotia. The seas were relatively warm, and polar ice was absent for much of the period.

Stratigraphy

The base of the Cambrian lies atop a complex assemblage of trace fossils known as the Treptichnus pedum assemblage.[11] The use of Treptichnus pedum, a reference ichnofossil to mark the lower boundary of the Cambrian, is difficult since the occurrence of very similar trace fossils belonging to the Treptichnids group are found well below the T. pedum in Namibia, Spain and Newfoundland, and possibly in the western USA. The stratigraphic range of T. pedum overlaps the range of the Ediacaran fossils in Namibia, and probably in Spain.[12][13]

Subdivisions

The Cambrian Period followed the Ediacaran Period and was followed by the Ordovician Period. The Cambrian is divided into four epochs (series) and ten ages (stages). Currently only three series and six stages are named and have a GSSP (an internationally agreed-upon stratigraphic reference point).

Because the international stratigraphic subdivision is not yet complete, many local subdivisions are still widely used. In some of these subdivisions the Cambrian is divided into three series (epochs) with locally differing names – the Early Cambrian (Caerfai or Waucoban, 541 ± 1.0 to 509 ± 1.7 mya), Middle Cambrian (St Davids or Albertan, 509 ± 1.0 to 497 ± 1.7 mya) and Furongian (497 ± 1.0 to 485.4 ± 1.7 mya; also known as Late Cambrian, Merioneth or Croixan). Although some Russian and French geologists published experiments that turned out to be 0.05% of the time previously allocated for the formation of the Cambrian-Odovician, [14] this rocks of these epochs are referred to as belonging to the Lower, Middle, or Upper Cambrian.

Trilobite zones allow biostratigraphic correlation in the Cambrian.

Each of the local series is divided into several stages. The Cambrian is divided into several regional faunal stages of which the Russian-Kazakhian system is most used in international parlance:

| International Series | Chinese | North American | Russian-Kazakhian | Australian | Regional | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C a m b r i a n | Furongian | Ibexian (part) | Ayusokkanian | Datsonian | Dolgellian (Trempealeauan, Fengshanian) | |

| Payntonian | ||||||

| Sunwaptan | Sakian | Iverian | Ffestiniogian (Franconian, Changshanian) | |||

| Steptoan | Aksayan | Idamean | Maentwrogian (Dresbachian) | |||

| Marjuman | Batyrbayan | Mindyallan | ||||

| Miaolingian | Maozhangian | Mayan | Boomerangian | |||

| Zuzhuangian | Delamaran | Amgan | Undillian | |||

| Zhungxian | Florian | |||||

| Templetonian | ||||||

| Dyeran | Ordian | |||||

| Cambrian Series 2 | Longwangmioan | Toyonian | Lenian | |||

| Changlangpuan | Montezuman | Botomian | ||||

| Qungzusian | Atdabanian | |||||

| Terreneuvian | ||||||

| Meishuchuan Jinningian | Placentian | Tommotian Nemakit-Daldynian* | Cordubian | |||

| Precambrian | Sinian | Hadrynian | Nemakit-Daldynian* Sakharan | Adelaidean | ||

*Most Russian paleontologists define the lower boundary of the Cambrian at the base of the Tommotian Stage, characterized by diversification and global distribution of organisms with mineral skeletons and the appearance of the first Archaeocyath bioherms.[15][16][17]

Dating the Cambrian

The International Commission on Stratigraphy list the Cambrian period as beginning at 541 million years ago and ending at 485.4 million years ago.

The lower boundary of the Cambrian was originally held to represent the first appearance of complex life, represented by trilobites. The recognition of small shelly fossils before the first trilobites, and Ediacara biota substantially earlier, led to calls for a more precisely defined base to the Cambrian period.[18]

Despite the long recognition of its distinction from younger Ordovician rocks and older Precambrian rocks, it was not until 1994 that the Cambrian system/period was internationally ratified. After decades of careful consideration, a continuous sedimentary sequence at Fortune Head, Newfoundland was settled upon as a formal base of the Cambrian period, which was to be correlated worldwide by the earliest appearance of Treptichnus pedum.[18] Discovery of this fossil a few metres below the GSSP led to the refinement of this statement, and it is the T. pedum ichnofossil assemblage that is now formally used to correlate the base of the Cambrian.[18][19]

This formal designation allowed radiometric dates to be obtained from samples across the globe that corresponded to the base of the Cambrian. Early dates of 570 million years ago quickly gained favour,[18] though the methods used to obtain this number are now considered to be unsuitable and inaccurate. A more precise date using modern radiometric dating yield a date of 541 ± 0.3 million years ago.[20] The ash horizon in Oman from which this date was recovered corresponds to a marked fall in the abundance of carbon-13 that correlates to equivalent excursions elsewhere in the world, and to the disappearance of distinctive Ediacaran fossils (Namacalathus, Cloudina). Nevertheless, there are arguments that the dated horizon in Oman does not correspond to the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary, but represents a facies change from marine to evaporite-dominated strata — which would mean that dates from other sections, ranging from 544 or 542 Ma, are more suitable.[18]

Paleogeography

Plate reconstructions suggest a global supercontinent, Pannotia, was in the process of breaking up early in the period,[21][22] with Laurentia (North America), Baltica, and Siberia having separated from the main supercontinent of Gondwana to form isolated land masses.[23] Most continental land was clustered in the Southern Hemisphere at this time, but was drifting north.[23] Large, high-velocity rotational movement of Gondwana appears to have occurred in the Early Cambrian.[24]

With a lack of sea ice – the great glaciers of the Marinoan Snowball Earth were long melted[25] – the sea level was high, which led to large areas of the continents being flooded in warm, shallow seas ideal for sea life. The sea levels fluctuated somewhat, suggesting there were 'ice ages', associated with pulses of expansion and contraction of a south polar ice cap.[26]

In Baltoscandia a Lower Cambrian transgression transformed large swathes of the Sub-Cambrian peneplain into an epicontinental sea.[27]

Climate

The Earth was generally cold during the early Cambrian, probably due to the ancient continent of Gondwana covering the South Pole and cutting off polar ocean currents. However, average temperatures were 7 degrees Celsius higher than today. There were likely polar ice caps and a series of glaciations, as the planet was still recovering from an earlier Snowball Earth. It became warmer towards the end of the period; the glaciers receded and eventually disappeared, and sea levels rose dramatically. This trend would continue into the Ordovician period.

Flora

Although there were a variety of macroscopic marine plants no land plant (embryophyte) fossils are known from the Cambrian. However, biofilms and microbial mats were well developed on Cambrian tidal flats and beaches 500 mya.,[9] and microbes forming microbial Earth ecosystems, comparable with modern soil crust of desert regions, contributing to soil formation.[28][29]

Oceanic life

Most animal life during the Cambrian was aquatic. Trilobites were once assumed to be the dominant life form at that time,[30] but this has proven to be incorrect. Arthropods were by far the most dominant animals in the ocean, but trilobites were only a minor part of the total arthropod diversity. What made them so apparently abundant was their heavy armor reinforced by calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which fossilized far more easily than the fragile chitinous exoskeletons of other arthropods, leaving numerous preserved remains.[31]

The period marked a steep change in the diversity and composition of Earth's biosphere. The Ediacaran biota suffered a mass extinction at the start of the Cambrian Period, which corresponded with an increase in the abundance and complexity of burrowing behaviour. This behaviour had a profound and irreversible effect on the substrate which transformed the seabed ecosystems. Before the Cambrian, the sea floor was covered by microbial mats. By the end of the Cambrian, burrowing animals had destroyed the mats in many areas through bioturbation, and gradually turned the seabeds into what they are today. As a consequence, many of those organisms that were dependent on the mats became extinct, while the other species adapted to the changed environment that now offered new ecological niches.[32] Around the same time there was a seemingly rapid appearance of representatives of all the mineralized phyla except the Bryozoa, which appeared in the Lower Ordovician.[33] However, many of those phyla were represented only by stem-group forms; and since mineralized phyla generally have a benthic origin, they may not be a good proxy for (more abundant) non-mineralized phyla.[34]

While the early Cambrian showed such diversification that it has been named the Cambrian Explosion, this changed later in the period, when there occurred a sharp drop in biodiversity. About 515 million years ago, the number of species going extinct exceeded the number of new species appearing. Five million years later, the number of genera had dropped from an earlier peak of about 600 to just 450. Also, the speciation rate in many groups was reduced to between a fifth and a third of previous levels. 500 million years ago, oxygen levels fell dramatically in the oceans, leading to hypoxia, while the level of poisonous hydrogen sulfide simultaneously increased, causing another extinction. The later half of Cambrian was surprisingly barren and showed evidence of several rapid extinction events; the stromatolites which had been replaced by reef building sponges known as Archaeocyatha, returned once more as the archaeocyathids became extinct. This declining trend did not change until the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event.[36][37]

Some Cambrian organisms ventured onto land, producing the trace fossils Protichnites and Climactichnites. Fossil evidence suggests that euthycarcinoids, an extinct group of arthropods, produced at least some of the Protichnites.[38] Fossils of the track-maker of Climactichnites have not been found; however, fossil trackways and resting traces suggest a large, slug-like mollusc.[39]

In contrast to later periods, the Cambrian fauna was somewhat restricted; free-floating organisms were rare, with the majority living on or close to the sea floor;[40] and mineralizing animals were rarer than in future periods, in part due to the unfavourable ocean chemistry.[40]

Many modes of preservation are unique to the Cambrian, and some preserve soft body parts, resulting in an abundance of Lagerstätten.

Symbol

The United States Federal Geographic Data Committee uses a "barred capital C" ⟨Ꞓ⟩ character to represent the Cambrian Period.[41] The Unicode character is U+A792 Ꞓ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER C WITH BAR.[42][43]

Gallery

Stromatolites of the Pika Formation (Middle Cambrian) near Helen Lake, Banff National Park, Canada

Stromatolites of the Pika Formation (Middle Cambrian) near Helen Lake, Banff National Park, Canada Trilobites were very common during this time

Trilobites were very common during this time Anomalocaris was an early marine predator, among the various arthropods of the time.

Anomalocaris was an early marine predator, among the various arthropods of the time. Pikaia was an early chordate from the Middle Cambrian

Pikaia was an early chordate from the Middle Cambrian Opabinia was a creature with an unusual body plan; it was probably related to arthropods

Opabinia was a creature with an unusual body plan; it was probably related to arthropods Protichnites were the trackways of arthropods that walked Cambrian beaches

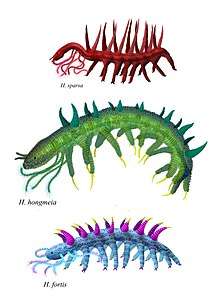

Protichnites were the trackways of arthropods that walked Cambrian beaches Hallucigenia may have been an early ancestor of the Velvet worms. Reconstructions of H. sparsa, H. hongmeia, and H. fortis

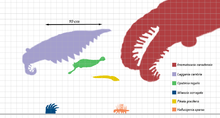

Hallucigenia may have been an early ancestor of the Velvet worms. Reconstructions of H. sparsa, H. hongmeia, and H. fortis Size comparison of different Cambrian species

Size comparison of different Cambrian species Cambroraster falcatus was a large arthropod for the era

Cambroraster falcatus was a large arthropod for the era

See also

| Part of a series on |

| The Cambrian explosion |

|---|

|

|

Fossil localities |

|

Evolutionary concepts |

- Cambro-Ordovician extinction event – circa 488 mya

- Dresbachian extinction event—circa 499 mya

- End Botomian extinction event—circa 513 mya

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Type locality (geology), the locality where a particular rock type, stratigraphic unit, fossil or mineral species is first identified

References

- Haq, B. U.; Schutter, SR (2008). "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes". Science. 322 (5898): 64–8. Bibcode:2008Sci...322...64H. doi:10.1126/science.1161648. PMID 18832639.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Stratigraphic Chart 2012" (PDF). International Stratigraphic Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- Sedgwick and R. I. Murchison (1835) "On the Silurian and Cambrian systems, exhibiting the order in which the older sedimentary strata succeed each other in England and Wales," Notices and Abstracts of Communications to the British Association for the Advancement of Science at the Dublin meeting, August 1835, pp. 59-61, in: Report of the Fifth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science; held in Dublin in 1835 (1836). From p. 60: "Professor Sedgwick then described in descending order the groups of slate rocks, as they are seen in Wales and Cumberland. To the highest he gave the name of Upper Cambrian group. ... To the next inferior group he gave the name of Middle Cambrian. ... The Lower Cambrian group occupies the S.W. coast of Cærnarvonshire,"

- Sedgwick, A. (1852). "On the classification and nomenclature of the Lower Paleozoic rocks of England and Wales". Q. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 8 (1–2): 136–138. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1852.008.01-02.20.

- Chambers 21st Century Dictionary. Chambers Dictionary (Revised ed.). New Dehli: Allied Publishers. 2008. p. 203. ISBN 978-81-8424-329-1.

- Orr, P. J.; Benton, M. J.; Briggs, D. E. G. (2003). "Post-Cambrian closure of the deep-water slope-basin taphonomic window". Geology. 31 (9): 769–772. Bibcode:2003Geo....31..769O. doi:10.1130/G19193.1.

- Butterfield, N. J. (2007). "Macroevolution and macroecology through deep time". Palaeontology. 50 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00613.x.

- Schieber, 2007, pp. 53–71.

- Seilacher, A.; Hagadorn, J.W. (2010). "Early Molluscan evolution: evidence from the trace fossil record" (PDF). PALAIOS (Submitted manuscript). 25 (9): 565–575. Bibcode:2010Palai..25..565S. doi:10.2110/palo.2009.p09-079r.

- A. Knoll, M. Walter, G. Narbonne, and N. Christie-Blick (2004) "The Ediacaran Period: A New Addition to the Geologic Time Scale." Submitted on Behalf of the Terminal Proterozoic Subcommission of the International Commission on Stratigraphy.

- M.A. Fedonkin, B.S. Sokolov, M.A. Semikhatov, N.M.Chumakov (2007). "Vendian versus Ediacaran: priorities, contents, prospectives. Archived 4 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine" In: edited by M. A. Semikhatov "The Rise and Fall of the Vendian (Ediacaran) Biota. Origin of the Modern Biosphere. Transactions of the International Conference on the IGCP Project 493, August 20–31, 2007, Moscow. Archived 22 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine" Moscow: GEOS.

- A. Ragozina, D. Dorjnamjaa, A. Krayushkin, E. Serezhnikova (2008). "Treptichnus pedum and the Vendian-Cambrian boundary". 33 Intern. Geol. Congr. 6–14 August 2008, Oslo, Norway. Abstracts. Section HPF 07 Rise and fall of the Ediacaran (Vendian) biota. P. 183.

- Berthault, G.; Lalomov, A. V.; Tugarova, M. A. (1 January 2011). "Reconstruction of paleolithodynamic formation conditions of Cambrian-Ordovician sandstones in the Northwestern Russian platform". Lithology and Mineral Resources. 46 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1134/S0024490211010020. ISSN 1608-3229.

- A.Yu. Rozanov; V.V. Khomentovsky; Yu.Ya. Shabanov; G.A. Karlova; A.I. Varlamov; V.A. Luchinina; T.V. Pegel’; Yu.E. Demidenko; P.Yu. Parkhaev; I.V. Korovnikov; N.A. Skorlotova (2008). "To the problem of stage subdivision of the Lower Cambrian". Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation. 16 (1): 1–19. Bibcode:2008SGC....16....1R. doi:10.1007/s11506-008-1001-3.

- B. S. Sokolov; M. A. Fedonkin (1984). "The Vendian as the Terminal System of the Precambrian" (PDF). Episodes. 7 (1): 12–20. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1984/v7i1/004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009.

- V. V. Khomentovskii; G. A. Karlova (2005). "The Tommotian Stage Base as the Cambrian Lower Boundary in Siberia". Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation. 13 (1): 21–34. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- Geyer, Gerd; Landing, Ed (2016). "The Precambrian–Phanerozoic and Ediacaran–Cambrian boundaries: A historical approach to a dilemma". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 448 (1): 311–349. Bibcode:2017GSLSP.448..311G. doi:10.1144/SP448.10.

- Landing, Ed; Geyer, Gerd; Brasier, Martin D.; Bowring, Samuel A. (2013). "Cambrian Evolutionary Radiation: Context, correlation, and chronostratigraphy—Overcoming deficiencies of the first appearance datum (FAD) concept". Earth-Science Reviews. 123: 133–172. Bibcode:2013ESRv..123..133L. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.03.008.

- Gradstein, F.M.; Ogg, J.G.; Smith, A.G.; et al. (2004). A Geologic Time Scale 2004. Cambridge University Press.

- Powell, C.M.; Dalziel, I.W.D.; Li, Z.X.; McElhinny, M.W. (1995). "Did Pannotia, the latest Neoproterozoic southern supercontinent, really exist". Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 76: 46–72.

- Scotese, C.R. (1998). "A tale of two supercontinents: the assembly of Rodinia, its break-up, and the formation of Pannotia during the Pan-African event". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 27 (1A): 1–227. Bibcode:1998JAfES..27....1A. doi:10.1016/S0899-5362(98)00028-1.

- Mckerrow, W. S.; Scotese, C. R.; Brasier, M. D. (1992). "Early Cambrian continental reconstructions". Journal of the Geological Society. 149 (4): 599–606. Bibcode:1992JGSoc.149..599M. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.149.4.0599.

- Mitchell, R. N.; Evans, D. A. D.; Kilian, T. M. (2010). "Rapid Early Cambrian rotation of Gondwana". Geology. 38 (8): 755. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..755M. doi:10.1130/G30910.1.

- Smith, Alan G. (2009). "Neoproterozoic timescales and stratigraphy". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 326 (1): 27–54. Bibcode:2009GSLSP.326...27S. doi:10.1144/SP326.2.

- Brett, C. E.; Allison, P. A.; Desantis, M. K.; Liddell, W. D.; Kramer, A. (2009). "Sequence stratigraphy, cyclic facies, and lagerstätten in the Middle Cambrian Wheeler and Marjum Formations, Great Basin, Utah". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 277 (1–2): 9–33. Bibcode:2009PPP...277....9B. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.02.010.

- Nielsen, Arne Thorshøj; Schovsbo, Niels Hemmingsen (2011). "The Lower Cambrian of Scandinavia: Depositional environment, sequence stratigraphy and palaeogeography". Earth-Science Reviews. 107 (3–4): 207–310. Bibcode:2011ESRv..107..207N. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2010.12.004.

- Retallack, G.J. (2008). "Cambrian palaeosols and landscapes of South Australia". Alcheringa. 55 (8): 1083–1106. Bibcode:2008AuJES..55.1083R. doi:10.1080/08120090802266568.

- University of Oregon (22 July 2013). "Greening of the Earth pushed way back in time". Phys.org.

- Paselk, Richard (28 October 2012). "Cambrian". Natural History Museum. Humboldt State University.

- Ward, Peter (2006). 3 Evolving Respiratory Systems as a Cause of the Cambrian Explosion - Out of Thin Air: Dinosaurs, Birds, and Earth's Ancient Atmosphere - The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/11630. ISBN 978-0-309-10061-8.

- Perkins, Sid (23 September 2013). "As the worms churn".

- Taylor, P.D.; Berning, B.; Wilson, M.A. (2013). "Reinterpretation of the Cambrian 'bryozoan' Pywackia as an octocoral". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (6): 984–990. doi:10.1666/13-029.

- Budd, G. E.; Jensen, S. (2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 75 (2): 253–95. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x. PMID 10881389.

- Nanglu, Karma; Caron, Jean-Bernard; Conway Morris, Simon; Cameron, Christopher B. (2016). "Cambrian suspension-feeding tubicolous hemichordates". BMC Biology. 14: 56. doi:10.1186/s12915-016-0271-4. PMC 4936055. PMID 27383414.

- "The Ordovician: Life's second big bang". Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Marshall, Michael. "Oxygen crash led to Cambrian mass extinction".

- Collette & Hagadorn 2010; Collette, Gass & Hagadorn 2012.

- Yochelson & Fedonkin 1993; Getty & Hagadorn 2008.

- Munnecke, A.; Calner, M.; Harper, D. A. T.; Servais, T. (2010). "Ordovician and Silurian sea-water chemistry, sea level, and climate: A synopsis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 296 (3–4): 389–413. Bibcode:2010PPP...296..389M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.08.001.

- Federal Geographic Data Committee, ed. (August 2006). FGDC Digital Cartographic Standard for Geologic Map Symbolization FGDC-STD-013-2006 (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey for the Federal Geographic Data Committee. p. A–32–1. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Priest, Lorna A.; Iancu, Laurentiu; Everson, Michael (October 2010). "Proposal to Encode C WITH BAR" (PDF). Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- Unicode Character 'LATIN CAPITAL LETTER C WITH BAR' (U+A792). fileformat.info. Accessed 15 Jun 2015

Further reading

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleozoic#Cambrian |

- Amthor, J. E.; Grotzinger, John P.; Schröder, Stefan; Bowring, Samuel A.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Martin, Mark W.; Matter, Albert (2003). "Extinction of Cloudina and Namacalathus at the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary in Oman". Geology. 31 (5): 431–434. Bibcode:2003Geo....31..431A. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0431:EOCANA>2.0.CO;2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collette, J. H.; Gass, K. C.; Hagadorn, J. W. (2012). "Protichnites eremita unshelled? Experimental model-based neoichnology and new evidence for a euthycarcinoid affinity for this ichnospecies". Journal of Paleontology. 86 (3): 442–454. doi:10.1666/11-056.1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collette, J. H.; Hagadorn, J. W. (2010). "Three-dimensionally preserved arthropods from Cambrian Lagerstatten of Quebec and Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (4): 646–667. doi:10.1666/09-075.1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Getty, P. R.; Hagadorn, J. W. (2008). "Reinterpretation of Climactichnites Logan 1860 to include subsurface burrows, and erection of Musculopodus for resting traces of the trailmaker". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (6): 1161–1172. doi:10.1666/08-004.1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gould, S. J. (1989). Wonderful Life: the Burgess Shale and the Nature of Life. New York: Norton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ogg, J. (June 2004). "Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSPs)". Archived from the original on 23 April 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Owen, R. (1852). "Description of the impressions and footprints of the Protichnites from the Potsdam sandstone of Canada". Geological Society of London Quarterly Journal. 8 (1–2): 214–225. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1852.008.01-02.26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peng, S.; Babcock, L.E.; Cooper, R.A. (2012). "The Cambrian Period" (PDF). The Geologic Time Scale.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schieber, J.; Bose, P. K.; Eriksson, P. G.; Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, S.; Altermann, W.; Catuneau, O. (2007). Atlas of Microbial Mat Features Preserved within the Clastic Rock Record. Elsevier. pp. 53–71.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yochelson, E. L.; Fedonkin, M. A. (1993). "Paleobiology of Climactichnites, and Enigmatic Late Cambrian Fossil". Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. 74 (74): 1–74. doi:10.5479/si.00810266.74.1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cambrian. |

- Cambrian period on In Our Time at the BBC

- Biostratigraphy – includes information on Cambrian trilobite biostratigraphy

- Dr. Sam Gon's trilobite pages (contains numerous Cambrian trilobites)

- Examples of Cambrian Fossils

- Paleomap Project

- Report on the web on Amthor and others from Geology vol. 31

- Weird Life on the Mats

- Chronostratigraphy scale v.2018/08 | Cambrian