Microsoft and open source

Microsoft, a technology company once known for its opposition to the open source software paradigm, turned to embrace the approach in the 2010s. From the 1970s through 2000s under CEOs Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer, Microsoft viewed the community creation and sharing of communal code, later to be known as free and open source software, as a threat to its business, and both executives spoke negatively against it. In the 2010s, as the industry turned towards cloud, embedded, and mobile computing—technologies powered by open source advances—CEO Satya Nadella led Microsoft towards open source adoption although Microsoft's traditional Windows business continued to grow throughout this period generating revenues of 26.8 billion in the third quarter of 2018, while Microsoft's Azure cloud revenues nearly doubled its revenue.[1] Microsoft open sourced some of its code, including the .NET Framework and Visual Studio Code, and made investments in Linux development, server technology, and organizations, including the Linux Foundation and Open Source Initiative. Linux-based operating systems power the company's Azure cloud services. Microsoft acquired GitHub, the largest host for open source project infrastructure, in 2018. Microsoft is among the site's most active contributors. This acquisition lead a few projects to migrate away from GitHub.[2] This proved a short lived phenomenon because by 2019 there were over 10 million new users of GitHub.

History

The paradigm of freely sharing computer source code—a practice known as open source—traces back to the earliest commercial computers, whose user groups shared code to reduce duplicate work and costs.[3] Following an antitrust suit that forced the unbundling of IBM's hardware and software, a proprietary software industry grew throughout the 1970s, in which companies sought to protect their software products. The technology company Microsoft was founded in this period and has long been an embodiment of the proprietary paradigm and its tension with open source practices, well before the terms "free software" or "open source" were coined. Within a year of founding Microsoft, Bill Gates wrote an open letter that positioned the hobbyist act of copying software as a form of theft.[4]

Microsoft successfully expanded in personal computer and enterprise server markets through the 1990s, partially on the strength of the company's marketing strategies.[5] By the late 1990s, Microsoft came to view the growing open source movement as a threat to their revenue and platform. Internal strategy memos from this period, known as the Halloween documents, describe the company's potential approaches to stopping open source momentum. One strategy was "embrace-extend-extinguish", in which Microsoft would adopt standard technology, add proprietary extensions, and upon establishing a customer base, would lock consumers into the proprietary extension to assert a monopoly of the space. The memos also acknowledged open source as a methodology capable of meeting or exceeding proprietary development methodology. Microsoft downplayed these memos as the opinions of an individual employee and not Microsoft's official position.[6]

While many major companies worked with open source software in the 2000s,[7] the decade was also marked by a "perennial war" between Microsoft and open source in which Microsoft continued to view open source as a scourge on its business[8] and developed a reputation as the archenemy of the free and open source movement.[9] Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer likened Linux to a kind of cancer on intellectual property. Microsoft sued Lindows, a Linux operating system that could run Microsoft Windows applications, as a trademark violation. The court rejected the claim and after Microsoft purchased its trademark, the software changed its name to Linspire.[8]

Adoption

In 2014, Satya Nadella was named the new CEO of Microsoft. Microsoft began to adopt open source into its core business. In contrast to Ballmer's stance, Nadella presented a slide that read, "Microsoft loves Linux".[9] At the time of the acquisition of GitHub, Nadella said of Microsoft, "We are all in on open source." As the industry trended towards cloud, embedded, and mobile computing, Microsoft turned to open source to stay apace in these open source dominated fields. Microsoft's adoption of open source included several surprising turns. In 2014, the company opened the source of its .NET Framework to promote its software ecosystem and stimulate cross-platform development. In 2016, Microsoft introduced Windows Subsystem for Linux, which lets Linux applications run on the Windows operating system. The company invested in Linux server technology and Linux development to promote cross-platform compatibility and collaboration with open source companies and communities, culminating with Microsoft's platinum sponsorship of the Linux Foundation and seat on its Board of Directors.[10] The Open Source Initiative, formerly a target of Microsoft, used the occasion of Microsoft's sponsorship in 2017 as a milestone for open source software's widespread acceptance. Microsoft delivered the keynote of the 2018 Southern California Linux Expo, a major convention.[11]

Microsoft developed Linux-based operating systems for use with its Azure cloud services. Azure Cloud Switch supports the Azure infrastructure and is based on open source and proprietary technology, and Azure Sphere powers Internet of things devices. As part of its announcement, Microsoft acknowledged Linux's role in small devices where the full Windows operating system would be unnecessary.[11]

In 2018, Microsoft acquired GitHub, the largest host for open source project infrastructure. Microsoft is among the site's most active contributors and the site hosts the source code for Microsoft's Visual Studio Code and .NET runtime system. The company, though, has received some criticism for only providing limited returns to the Linux community, since the GPL license lets Microsoft modify Linux source code for internal use without sharing those changes.[12] In 2019, Microsoft's Windows Subsystem for Linux 2 transitioned from an emulated Linux kernel to a full Linux kernel within a virtual machine, improving processor performance manifold. In-keeping with the GPL open source license, Microsoft will submit its kernel improvements for accommodation into the master, public release.[13]

Microsoft transitioned its Edge browser to use the open source Chromium (also the basis for Google Chrome) in 2019.[14]

Selected products

- .NET Bio – Bioinformatics and genomics library created to enable simple loading, saving and analysis of biological data

- .NET Compiler Platform (Roslyn) – Compilers and code analysis APIs for C# and Visual Basic .NET programming languages

- .NET Core – Software framework[10]

- .NET Gadgeteer – Rapid-prototyping standard for building small electronic devices

- .NET MAUI – A cross-platform UI toolkit

- .NET Micro Framework – .NET Framework platform for resource-constrained devices

- AirSim – Simulator for drones, cars and other objects, built as a platform for AI research

- Allegiance – Multiplayer online game providing a mix of real-time strategy and player piloted space combat gameplay

- ASP.NET

- ASP.NET AJAX

- ASP.NET Core

- ASP.NET MVC

- ASP.NET Razor

- ASP.NET Web Forms

- Atom – Text and source code editor for macOS, Linux, and Microsoft Windows

- BitFunnel – A signature-based search engine

- Blazor – Web framework that enables developers to create web apps using C# and HTML

- Bosque – Functional programming language[15]

- C++/WinRT – C++ library for Microsoft's Windows Runtime platform, designed to provide access to modern Windows APIs

- C# – General-purpose, multi-paradigm programming language encompassing strong typing, lexically scoped, imperative, declarative, functional, generic, object-oriented (class-based), and component-oriented programming disciplines

- ChakraCore – JavaScript engine

- ChronoZoom – Project that visualizes time on the broadest possible scale from the Big Bang to the present day

- CLR Profiler – Memory profiler for the .NET Framework

- Conference XP – Video conferencing platform

- Dafny – Imperative compiled language that targets C# and supports formal specification through preconditions, postconditions, loop invariants and loop variants

- DeepSpeed – Deep learning optimization library for PyTorch

- Detours – C++ library for intercepting, monitoring and instrumenting binary functions on Microsoft Windows

- DiskSpd – Command-line tool for storage benchmarking that generates a variety of requests against computer files, partitions or storage devices

- Dynamic Language Runtime – Runtime that runs on top of the CLR and provides computer language services for dynamic languages

- F* – Functional programming language inspired by ML and aimed at program verification

- F# – General purpose, strongly typed, multi-paradigm programming language that encompasses functional, imperative, and object-oriented programming methods

- File Manager – File manager for Microsoft Windows

- Fluid Framework, a platform for real-time collaboration across applications[16]

- FourQlib – Reference implementation of the FourQ elliptic curve

- GW-BASIC – Dialect of the BASIC programming language

- Microsoft C++ Standard Library – Implementation of the C++ Standard Library (also known as the STL)[17]

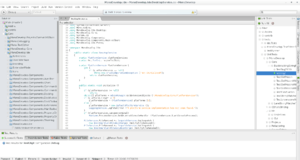

- MonoDevelop – Integrated development environment for Linux, macOS, and Windows

- MSBuild – Build tool set for managed code as well as native C++ code

- MsQuic – Implementation of the IETF QUIC protocol

- Neural Network Intelligence – An AutoML toolkit

- Open Live Writer – Desktop blogging application

- Open Management Infrastructure – CIM management server

- Open XML SDK – set of managed code libraries to create and manipulate Office Open XML files programmatically

- Orleans – Cross-platform software framework for building scalable and robust distributed applications based on the .NET Framework

- P – Programming language for asynchronous event-driven programming and the IoT

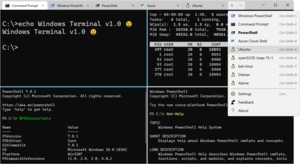

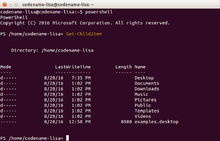

- PowerShell – Command-line shell and scripting language[18]

- Process Monitor – Tool that monitors and displays in real-time all file system activity

- ProcDump – Command-line application for creating crash dumps during a CPU spike[19]

- Project Mu – UEFI core used in Microsoft Surface and Hyper-V products

- PowerToys for Windows 10 – System utilities for power users

- RecursiveExtractor – An archive file extraction library written in C#

- Sandcastle – Documentation generator

- StyleCop – Static code analysis tool that checks C# code for conformance to recommended coding styles and a subset of the .NET Framework design guidelines

- TypeScript – Programming language similar to JavaScript, among the most popular on GitHub[20]

- U-Prove – Cross-platform technology and accompanying SDK for user-centric identity management

- vcpkg – Cross-platform package manager used to simplify the acquisition and installation of third-party libraries

- VFS for Git – Virtual file system extension to the Git version control system

- Visual Basic .NET – Multi-paradigm, object-oriented programming language

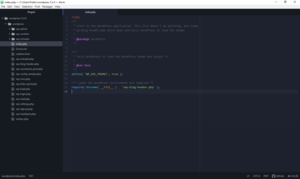

- Visual Studio Code – Source code editor and debugger for Windows, Linux and macOS,[12] and GitHub's top open source project[20]

- Vowpal Wabbit – online interactive machine learning system library and program

- WikiBhasha – Multi-lingual content creation application for the Wikipedia online encyclopedia

- Windows Calculator – Software calculator[21][22]

- Windows Communication Foundation – runtime and a set of APIs for building connected, service-oriented applications

- Windows Console – Terminal emulator

- Windows Driver Frameworks – Tools and libraries that aid in the creation of device drivers for Microsoft Windows

- Windows Forms – Graphical user interface (GUI) class library

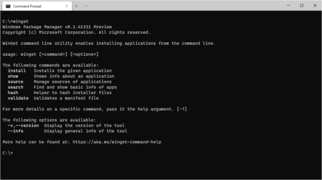

- Windows Package Manager – Package manager for Windows 10

- Windows Presentation Foundation – Graphical subsystem (similar to WinForms) for rendering user interfaces in Windows-based applications

- Windows Template Library – Object-oriented C++ template library for Win32 development

- Windows Terminal – Terminal emulator[23][24]

- Windows UI Library – Set of UI controls and features for the Universal Windows Platform (UWP)

- WinJS – JavaScript library for cross-platform app development

- WinObjC – Middleware toolkit that allows iOS apps developed in Objective-C to be ported to Windows 10

- WiX (Windows Installer XML Toolset) – Toolset for building Windows Installer packages from XML

- WorldWide Telescope – Astronomy software

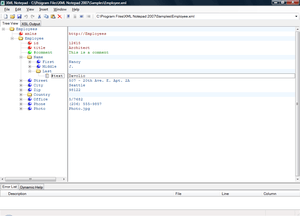

- XML Notepad – XML editor

- XSP – Standalone web server written in C# that hosts ASP.NET for Unix-like operating systems

- xUnit.net – Unit testing tool for the .NET Framework

- Z3 Theorem Prover – Cross-platform satisfiability modulo theories (SMT) solver

See also

References

- Bright, Peter (April 26, 2018). "Even Windows revenue is up in Microsoft's $26.8 billion 3Q18". Ars Technica. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- "GitHub rivals gain from Microsoft acquisition but it's no mass exodus, yet". ZDNet. May 6, 2019.

- Radits 2019, pp. 13–14.

- Radits 2019, pp. 17–18.

- Radits 2019, pp. 27–28.

- Radits 2019, p. 27.

- Radits 2019, p. 30.

- Radits 2019, p. 31.

- Radits 2019, p. 32.

- Radits 2019, p. 33.

- Radits 2019, p. 34.

- Radits 2019, p. 35.

- Bright, Peter (May 6, 2019). "Windows 10 will soon ship with a full, open source, GPLed Linux kernel". Ars Technica. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (May 6, 2019). "Inside Microsoft's surprise decision to work with Google on its Edge browser". The Verge. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Krill, Paul (April 18, 2019). "Microsoft aims for simplicity with Bosque programming language". InfoWorld. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (May 19, 2020). "Microsoft's new Fluid Office document is Google Docs on steroids". The Verge. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- https://devblogs.microsoft.com/cppblog/open-sourcing-msvcs-stl/

- PowerShell

- ProcDump - Monitor CPU/processes - Windows CMD - SS64.com

- Chan, Rosalie (November 9, 2019). "The 10 most popular programming languages, according to the Microsoft-owned GitHub". Business Insider. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (March 6, 2019). "Microsoft open-sources its Windows calculator on GitHub". The Verge. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Archambault, Michael (March 6, 2019). "Microsoft Continues Open-Source Effort, Releases Calculator Code". Digital Trends. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Bowden, Zac (May 19, 2020). "Microsoft's open source Windows Terminal app reaches stable release". Windows Central. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Warren, Tom (May 6, 2019). "Microsoft unveils Windows Terminal, a new command line app for Windows". The Verge. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

Bibliography

- Radits, Markus (January 25, 2019). A Business Ecology Perspective on Community-Driven Open Source: The Case of the Free and Open Source Content Management System Joomla. Linköping University Electronic Press. ISBN 978-91-7685-305-4.

Further reading

- Asay, Matt (October 30, 2017). "Why Microsoft and Google are now leading the open source revolution". TechRepublic. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Bright, Peter (May 10, 2019). "Microsoft: The open source company". Ars Technica. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- Gartenberg, Chaim (October 10, 2018). "Microsoft makes its 60,000 patents open source to help Linux". The Verge. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Hayes, Frank (March 19, 2001). "The Microsoft Way". Computerworld. 35 (12). p. 78. ISSN 0010-4841.

- Ovide, Shira (April 16, 2012). "Microsoft Dips Further Into Open-Source Software". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660.

- Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (October 29, 2014). "Why Microsoft loves Linux". ZDNet. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (January 26, 2015). "Microsoft: The open-source company". ZDNet. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (June 9, 2016). "Why Microsoft is turning into an open-source company". ZDNet. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (October 10, 2018). "Microsoft open-sources its patent portfolio". ZDNet. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (December 30, 2019). "Linux and open-source rules: 2019's five biggest stories show why". ZDNet. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (April 29, 2019). "How Microsoft learned from the past to redesign its future". The Verge. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- Warren, Tom (May 18, 2020). "Microsoft: we were wrong about open source". The Verge. Retrieved May 20, 2020.