Mesocarnivore

A mesocarnivore is an animal whose diet consists of 50–70% meat with the balance consisting of non-animal foods which may include insects, fungi, fruits, other plant material and any food that is available to them .[1] Mesocarnivores are from a large family group of mammalian carnivores and vary from small to medium sized, which are less than fifteen kilograms.[2] Mesocarnivores are seen today among the Canidae (coyotes, foxes), Viverridae (civets), Mustelidae (martens, tayra), Procyonidae (ringtail, raccoon), Mephitidae (skunks), and Herpestidae (some mongooses). The red fox is also the most common of the mesocarnivores in Europe and has a high population density in the areas they reside.[3]

In North America, though some mesocarnivores, such as otters, lynx, or marten, are in danger of being over hunted for their pelts.[4] This has led to efforts to help protect and conserve the mesocarnivores in the area which have been largely successful thus far.[5] These animals play an essential role in the function and system of the ecosystem, since the elimination of apex predators.

The American Institute of Biological Sciences states that due to the fact that mesocarnivores are smaller than large carnivore, they are more abundant, and therefore have a diversity of mesocarnivore species.[2] Due to their smaller size, mesocarnivores play a part in the ecosystem of dispersing seeds in open spaces, as well as driving community structure.[2] Mesocarnivores are also very diverse in comparison to larger carnivores in their behaviour and ecology, from being reclusive to highly social. Their diversity and small size allows them to thrive in a range of habitats than larger carnivores are able to.[2] The population of these smaller carnivores also increases when the presence of a larger carnivore decline. This is known as the 'mesocarnivore release.' According to the National Park Service, "Mesocarnivore release is defined as the expansion in range and/or abundance of a smaller predator following the reduction or removal of a larger predator."[6] One impact of this is that these mesocarnivores can act as scavengers cleaning up dead animal carcasses discarded by humans in urban areas.[7] Mesocarnivores' habitat have shifted and changed, due to urbanisation, leading to habitat fragmentation and disturbance, resulting in habitat loss for animals.

Evolution

Mesocarnivores, as a part of the mammalian carnivore family, play a large role in the ecosystem, due to their prey-drive effects and impact on its functionality and structure. They are an important part of the ecological function, as their size to medium size allows them to disperse seeds, that, hypercarnivores cannot.[2] Mesocarnivores transport seeds in open spaces, as far as one kilometre and disperse seeds within 600 to 750 metres of each other.[2] They can influence other native carnivores by predation and competition in the ecosystem, and can lead to a reduction or possible extinction of prey species and effect geographical distribution, changing the structure of the ecosystem.[2] Mesocarnivores also serve other ecological roles such as its position in the food web and disease mitigation.[8] Mesocarnivores' habitats are rapidly changing due to urbanisation, habitat fragmentation and deforestation, which is a threat to survival for these animals, due to habitat loss and can cause a decrease in species.[4] Some mesocarnivores have adapted very quickly to the constantly changing habitat conditions, compared to other mesocarnivores, for example the coyote (canis latrans) in Northeast North America.[4] Many carnivores have different locomotor movements and are easily adaptable to a range of habitats and source various foods.[9]

Characteristics

Behaviour and Activity

Some mesocarnivores including the masked palm civet, hog badger and leopard cat activity patterns peaked during the night.[10] Mesocarnivores activity levels change within different seasons and climates. Different temperatures and the rate of plant growth may affect the activity patterns in mesocarnivores.[11] Masked palm civets in China do not appear often in the winter months (December to February) and are not as active.[10] Mesocarnivores’ behaviour and characteristics are individual to their species. For example, coyotes are pack animals and form strong family relations. The way mesocarnivores communicate with each other is through their behaviours that are able to organise mating systems, distinguish parental care and other behaviours.[9] Carnivores also use their senses to communicate with other animals and in the pack, especially their olfactory senses.[9]

Mesocarnivores perform a wide range of different movements. Different species of mesocarnivores can achieve different types of locomotor movements. For example, otters (Lutrinae) are specialised in swimming in water, however find it difficult to move on land. Other carnivores can improve their locomotor movements by behaviour modifications, for example, the African lion and gray wolf demonstrate group hunting behaviour where it allows them to run and hunt prey as a pack, that can not be done individually.[9] Carnivores with limbs that are adapted for running may run, gallop or pace to go at a fast pace and cover long distances.[9] These carnivorous mammals use their gait which is dependent on their species and size. The structure of a carnivore is designed to catch prey and kill it.

Feeding behaviours

Mesocarnivores are found to be nocturnal and are hunting for prey when they are most active during the nighttime.[11] Mesocarnivores’ feeding behaviours mainly consist of prey availability. They feed on small mammals which include a range of different mice and squirrels, such as the northern grasshopper mice, ord’s kangaroo rat and thirteen-lined ground squirrels.[12] Some other examples of mesocarnivores’ prey are the blacktailed jackrabbit and the desert cottontail.[12] Large and small mammals are considered as prey to these mesocarnivores, as well as different herbivores, depending on what food is most readily available to these animals. Without apex predators, there is a decreased level of inter-specific competition in the food chain between mesocarnivores, allowing them to increase their scavenging options for different food.[13] As mesocarnivores are scavengers, they will eat any food that is accessible to them. For example, the yellow-throated marten and Siberian weasel change their feeding behaviours in winter when limited fruits are available and convert to small mammal prey.[10] Mesocarnivores are closely related to other mammals in regards to competition and intraguild predation. Interspecific competition is a vital part of the ecological species and community structure, as a result can lead to "exploitation competition" and "interference competition" with other species. [14]

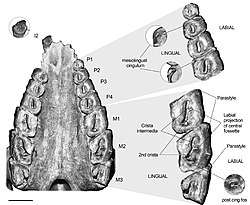

Dentition

Mesocarnivore cheek teeth are heterodont and their different shapes reflect distinct functions. Incisors and canines are used to apprehend food and kill prey, pointed premolars pierce and hold prey, and molars are involved in both slicing and crushing functions. The slicing function of the molars is produced by occlusion between the carnassials, the lower first molar, and the upper fourth premolar.

Mesocarnivores are first represented by the Miacidae. They are best represented by Prohesperocyon, with three incisors, one canine tooth, four premolars above. The jaw has three molars below, and two molars above on each side.[15]

Taxonomy

There are many animals in the wild that are considered as mesocarnivores, such as species of lynx, bobcat, American marten, fisher, river otter, American mink, coyote, red fox, gray fox, raccoon, striped skunk, weasels.[4] Individual species' diets may vary, depending on the season and what food can be sourced. Mesocarnivore mammals have a large role in the ecosystem that impacts ecological community and system in the environment.

Example species

Coyote (Canis Latrans)

The coyote (canis latrans) is a native species to North America. They can live up to a lifespan of fourteen years, with their size ranging from 81-94 cm (32 to 37 inch) head to body, and weigh 9-23 kg (20-50 pounds).[16] Coyotes’ diet mostly consists of mammals, fruits, birds, grass and insects. They are also hunters and will eat anything of readily available prey including rabbits, fish, lamb. The coyotes in the wild enjoy intense smells of adventure and prey, as well as having an excellent sense of vision. They are pack animals and hunt prey and food in a pack, especially in the fall and winter.

River Otter (Lontra Canadensis)

The river otter is one of North America’s native animals. They have an average lifespan of 8 to 9 years, with a body length ranging from 56-80 cm (22-32 inch) head to body and weigh 5-13 kg (11-30 pounds).[17] The river otter’s habitat is in water and on land. They create a burrow near the water as their den and easily adapt to other aquatic habitats.[4] They hunt during the night, and find food that is readily available to them. River otters have great swimming abilities and stay active during winter.

Raccoon (Procyon Lotor)

There are several raccoon species which are also known as ringtail, all originated from the United States. Their physical characteristics include short limbs, a pointed snout and small upright ears, with a body length of 75-90 cm (30-35 inch) long.[18] Raccoons weight varies from 10-20 kg (22-44 pounds) and have a furry coat that resembles black, grey and brown shades.[18] These mesocarnivores catch majority of their food in water, including crayfish, frogs and other marine animals, as well as feeding on rodents and other plant material. Some species of the raccoon include the Barbados raccoon (P. gloveralleni), Tres Marías raccoon (P. insularis), Bahaman raccoon (P. maynardi), Guadeloupe raccoon (P. minor) and Cozumel raccoon (P. pygmaeus).

Mongoose (Herpestidae)

The mongoose is a species of mesocarnivores which are mainly located in Africa, southern Asia and southern Europe. They are known for their predatory attacks on snakes. The meerkat is known as a part of the mongoose family of mesocarnivores. Mongooses are animals with physical features including short legs, pointed snout, minute ears and a long tail. Their fur colour resembles grey to brown shades and have specks of lighter grey. The mongoose ranges in size from the smallest, dwarf mongoose, 17-24 cm (7-10 inch) in body length and the largest mongoose of 48-74 cm (19-29 inch) in body length.[19] Dwarf mongoose have a tail approximately 15-20 cm (6-8 inch) long, and larger mongooses have a longer tail up to 40 cm (19 inch) long.

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

The red fox is a species part of the fox family, which is located in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. Its body length is usually approximately 90-105 cm (35-41 inch) long, 30-40 cm (12-16 inch) of its body length being its tail, and is a height of 40 cm (16 inch).[20] Many adult red foxes weigh 5-7 kg (11-15 pounds) and can reach up to 14 kg (31 pounds).[20] The physical characteristics of the red fox have a soft thin undercoat and long hairs that consists of orange, red, brown shades. The red fox has black ears and legs, with white on the tip of its tail and on its chest. Red foxes live in a range of habitats which include grasslands, forests, mountains and deserts.

Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis)

The striped skunk is a mesocarnivore species that are located in the United States. Their physical characteristics in size range from 20-25 cm (8-10 inch) from head to body, with a 12-38 cm (5-15 inch) tail.[21] Striped skunks weigh between 200g-6 kg (7 ounces-14 pounds) and have an average lifespan of 3 years. They are easily adaptable animals that live in forests, woodlands and grasslands. These mesocarnivores can be easily recognized by their black fur with a thin white stripe from their nose to their forehead. There are two thick white stripes that run along the sides of their back and continue to their furry, bushy tail with grey shades. Striped skunks are known for their predatory skunk spray, where oily liquid is released by its glands, resulting in a foul odor to their predators.[21]

Marten (Mustalidae)

The marten is a mesocarnivore species which are found in Canada, United States, Africa, Asia and Europe. There are many different species of the marten. Their physical characteristics include a variation in size and colour from yellow to shades of dark brown, have short legs, small, round ears and have slender bodies, with thick coats.[22] Their body length ranges from 35-65 cm (14-26 inch), with a long tail of 3-7 cm (9-18 inch), depending on the species and weigh 1-2kg (2-4 pounds).[22] Some species of the marten include American marten, pine marten, stone marten, yellow-throated marten, and nilgiri marten.

- Species of Mesocarnivores

Coyote (canis latrans)

Coyote (canis latrans).jpg) River Otter (Lontra canadensis)

River Otter (Lontra canadensis).jpg) Mongoose (Herpestidae)

Mongoose (Herpestidae) Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes).jpg) Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis)

Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis)01.jpg) Stone marten (Martes foina)

Stone marten (Martes foina)

References

- Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (2007). "Déjà vu: the evolution of feeding morphologies in the Carnivora". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 147–163. doi:10.1093/icb/icm016. PMID 21672827.

- Gary W. Roemer, Matthew E. Gompper, Blaire Van Valkenburgh, "The Ecological Role of the Mammalian Mesocarnivore", BioScience, Volume 59, Issue 2, February 2009, Pages 165–173, https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2009.59.2.9

- Sándor, Attila D.; et al. "Mesocarnivores and Macroparasites: Altitude and Land Use Predict the Ticks Occurring on Red Foxes (Vulpes Vulpes)". Parasites & Vectors. 10: 1–9. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2113-9.

- Ray, Justina C. Mesocarnivores of Northeastern North America: Status and Conservation Issues. WCS Working Papers No. 15, June 2000. Available for download from http://www.wcs.org/science/

- "Comeback Kids: Mesocarnivores Rebound in Northeastern U.S." CNN, Cable News Network, 2000, www.cnn.com/2000/NATURE/08/09/carnivores.enn/index.html.

- "Scavenging and Landscape Use of Mesocarnivores in Denali (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2019, www.nps.gov/articles/denali-crp-mesocarnivore.htm.

- Ćirović, Duško & Penezić, Aleksandra & Krofel, Miha. (2016). Jackals as cleaners: Ecosystem services provided by a mesocarnivore in human-dominated landscapes. Biological Conservation. 199. 51-55. 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.04.027.

- Curveira-Santos, Gonçalo; Pedroso, Nuno M.; Barros, Ana Luísa; Santos-Reis, Margarida (2019-01-17). "Mesocarnivore community structure under predator control: Unintended patterns in a conservation context". PLOS ONE. 14 (1): e0210661. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210661. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6336399. PMID 30653547.

- Gittleman, John L. (2013-03-09). Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4757-4716-4.

- Bu, Hongliang; Wang, Fang; McShea, William J.; Lu, Zhi; Wang, Dajun; Li, Sheng (2016-10-10). "Spatial Co-Occurrence and Activity Patterns of Mesocarnivores in the Temperate Forests of Southwest China". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0164271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164271. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5056745. PMID 27723772.

- Penido, Gabriel; Astete, Samuel; Jácomo, Anah T. A.; Sollmann, Rahel; Tôrres, Natalia; Silveira, Leandro; Marinho Filho, Jader (2017-12-01). "Mesocarnivore activity patterns in the semiarid Caatinga: limited by the harsh environment or affected by interspecific interactions?". Journal of Mammalogy. 98 (6): 1732–1740. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyx119. ISSN 0022-2372.

- Thompson, Craig M.; Gese, Eric M. (2007). "Food Webs and Intraguild Predation: Community Interactions of a Native Mesocarnivore". Ecology. 88 (2): 334–346. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[334:FWAIPC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1939-9170.

- Yarnell, Richard W.; Phipps, W. Louis; Burgess, Luke P.; Ellis, Joseph A.; Harrison, Stephen W.R.; Dell, Steve; MacTavish, Dougal; MacTavish, Lynne M.; Scott, Dawn M. (October 2013). "The Influence of Large Predators on the Feeding Ecology of Two African Mesocarnivores: The Black-Backed Jackal and the Brown Hyaena". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 43 (2): 155–166. doi:10.3957/056.043.0206. ISSN 0379-4369.

- Remonti, Luigi; Balestrieri, Alessandro; Ruiz-González, Aritz; Gómez-Moliner, Benjamín J.; Capelli, Enrica; Prigioni, Claudio (2012-10-01). "Intraguild dietary overlap and its possible relationship to the coexistence of mesocarnivores in intensive agricultural habitats". Population Ecology. 54 (4): 521–532. doi:10.1007/s10144-012-0326-5. ISSN 1438-390X.

- Radinsky, L.B. (1982). "Evolution of skull shape in carnivores. 3. The origin and early radiation of the modern carnivore families". Paleobiology. 8: 177–95. doi:10.1017/S0094837300006928.

- "Coyote | National Geographic". Animals. 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "North American River Otter | National Geographic". Animals. 2010-11-11. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "Raccoon | mammal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "mongoose | Species & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "red fox | Diet, Behaviour, & Adaptations". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "Striped Skunk | National Geographic". Animals. 2010-11-11. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "Marten | mammal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-02.