Meningoencephalitis

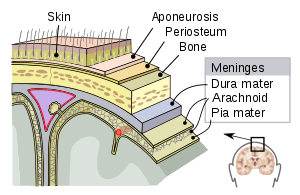

Meningoencephalitis (/mɪˌnɪŋɡoʊɛnˌsɛfəˈlaɪtɪs, -ˌnɪndʒoʊ-, -ən-, -ˌkɛ-/;[3][4] from Greek μῆνιγξ meninx, "membrane", ἐγκέφαλος, enképhalos "brain", and the medical suffix -itis, "inflammation"), also known as herpes meningoencephalitis, is a medical condition that simultaneously resembles both meningitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the meninges, and encephalitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the brain.

| Meningoencephalitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Herpes meningoencephalitis[1][2] |

| |

| Meninges | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, neurology |

Signs and symptoms

Signs of meningeoncephalitis include unusual behavior, personality changes, and thinking problems.[1][5]

Symptoms may include headache, fever, pain in neck movement, light sensitivity, and seizure.[2]

Causes

Causative organisms include protozoans, viral and bacterial pathogens.

Specific types include:

Bacterial

Veterinarians have observed meningoencephalitis in animals infected with listeriosis, caused by the pathogenic bacteria L. monocytogenes. Meningitis and encephalitis already present in the brain or spinal cord of an animal may form simultaneously into meningeoencephalitis.[6] The bacterium commonly targets the sensitive structures of the brain stem. L. monocytogenes meningoencephalitis has been documented to significantly increase the number of cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-12, IL-15, leading to toxic effects on the brain.[7]

Meningoencephalitis may be one of the severe complications of diseases originating from several Rickettsia species, such as Rickettsia rickettsii (agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF)), Rickettsia conorii, Rickettsia prowazekii (agent of epidemic louse-borne typhus), and Rickettsia africae. It can cause impairments to the cranial nerves, paralysis to the eyes, and sudden hearing loss.[8][9] Meningoencephalitis is a rare, late-stage manifestation of tick-borne ricksettial diseases, such as RMSF and Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME), caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis (a species of rickettsiales bacteria).[10]

Other bacteria that can cause it are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Tuberculosis, Borrelia (Lyme disease) and Leptospirosis.

Viral

- Tick-borne encephalitis

- West Nile virus

- Measles

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Varicella-zoster virus

- Enterovirus

- Herpes simplex virus type 1

- Herpes simplex virus type 2

- Rabies virus

- Mumps, a relatively common cause of meningoencephalitis. However, most cases are mild, and mumps meningoencephalitis generally does not result in death or neurologic sequelae.[11]

- HIV, a very small number of individuals exhibit meningoencephalitis at the primary stage of infection.[12][13]

Autoimmune

- Antibodies targeting amyloid beta peptide proteins which have been used during research on Alzheimer's disease.[14]

- Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (anti-NMDA) receptor antibodies, which are also associated with seizures and a movement disorder, and related to Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

- NAIM or "Nonvasculitic autoimmune inflammatory meningoencephalitis" (NAIM).[15] They can be divided into GFAP- and GFAP+ cases. The second is related to the Autoimmune GFAP Astrocytopathy.

Protozoal

Other/multiple

Other causes include granulomatous meningoencephalitis and vasculitis. The fungus, Cryptococcus neoformans, can be symptomatically manifested within the CNS as meningoencephalitis with hydrocephalus being a very characteristic finding due to the unique thick polysaccharide capsule of the organism.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis includes evaluation for the presence of recurrent or recent herpes infection, fever, headache, altered mental status, convulsions, disturbance of consciousness, and focal signs.

CSF, EEG, CT, MRI are responsive to specific antivirus agent.

Definite diagnosis – besides the above, the following are needed: CSF: HSV-antigen, HSV-Antibody, brain biopsy or pathology: Cowdry in intranuclear

CSF: the DNA of the HSV(PCR)

cerebral tissue or specimen of the CSF:HSV

except other viral encephalitis

Treatment

Antiviral therapy, such as acyclovir and ganciclovir, work best when applied as early as possible. May also be treated with interferon as an immune therapy.

Symptomatic therapy can be applied as needed. High fever can be treated by physical regulation of body temperature. Seizure can be treated with antiepileptic drugs. High intracranial pressure can be treated with drugs such as mannitol.

If caused by an infection then the infection can be treated with antibiotic drugs.

See also

- Meningitis

- Meningism

- Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis

- Encephalitis

- Naegleria fowleri

References

- "Herpes Meningoencephalitis". Johns Hopkins Medicine. The Johns Hopkins University, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Herpes Meningoencephalitis". Columbia University Department of Neurology. Columbia University. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Meningoencephalitis". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Meningoencephalitis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- Shelat, Amit; Ziegler, Olivia. "Herpes Meningoencephalitis". University of Rochester Medical Center - Health Encyclopedia. University of Rochester Medical Center Rochester, NY. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Long, Maureen. "Overview of Meningitis, Encephalitis, and Encephalomyelitis". Merck Manual: Veterinary Manual. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Deckert, Martina; Soltek, Sabine; Geginat, Gernot; Lütjen, Sonja; Montesinos-Rongen, Manuel; Hof, Herbert; Schlüter, Durk (July 2001). "Endogenous Interleukin-10 Is Required for Prevention of a Hyperinflammatory Intracerebral Immune Response in Listeria monocytogenes Meningoencephalitis". Infect. Immun. 69 (7): 4561–4571. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.7.4561-4571.2001. PMC 98533. PMID 11402000.

- Biggs, Holly (2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis — United States". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 65 (2): 1–44. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1. PMID 27172113.

- Ryan, Edward; Durand, Marlene (2011). "CHAPTER 135 - Ocular Disease". Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice (Third Edition). III: 991–1016. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-3935-5.00135-X. ISBN 9780702039355.

- Huntzinger, Amber (July 2007). "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Tick-Borne Rickettsial Diseases". American Family Physician. American Academy of Family Physicians. 76 (1): 137. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Bruyn HB, Sexton HM, Brainerd HD (March 1957). "Mumps meningoencephalitis; a clinical review of 119 cases with one death". Calif Med. 86 (3): 153–60. PMC 1512024. PMID 13404512.

- Newton, PJ; Newsholme, W; Brink, NS; Manji, H; Williams, IG; Miller, RF (2002). "Acute meningoencephalitis and meningitis due to primary HIV infection". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 325 (7374): 1225–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1225. PMC 1124692. PMID 12446542.

- Del Saz, SV; Sued, O; Falcó, V; Agüero, F; Crespo, M; Pumarola, T; Curran, A; Gatell, JM; et al. (2008). "Acute meningoencephalitis due to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in 13 patients: clinical description and follow-up". Journal of NeuroVirology. 14 (6): 474–9. doi:10.1080/13550280802195367. PMID 19037815.

- Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, et al. (2003-07-08). "Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Aß42 immunization". Neurology. 61 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000073623.84147.A8. PMID 12847155.

- Keith A Josephs, Frank A Rubino, Dennis W Dickson, Nonvasculitic autoimmune inflammatory meningoencephalitis, Neuropathology 24(2):149-52 · July 2004, DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00542.x

- "Rare parasitic worm kills two kidney donor patients, inquest hears". The Guardian. 2014-11-18. Retrieved 2014-11-24.