William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an eminent English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, but his real talent was for design in various media.

William Kent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | late 1685 |

| Died | 12 April 1748 (aged 62) Burlington House, London |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Holkham Hall Chiswick House 44 Berkeley Square Badminton House Stowe House |

| Projects | Palladian style English landscape garden |

Kent introduced the Palladian style of architecture into England with the villa at Chiswick House, and also originated the 'natural' style of gardening known as the English landscape garden at Chiswick, Stowe House in Buckinghamshire, and Rousham House in Oxfordshire. As a landscape gardener he revolutionised the layout of estates, but had limited knowledge of horticulture.

He complemented his houses and gardens with stately furniture for major buildings including Hampton Court Palace, Chiswick House, Devonshire House and Rousham.

Early life

Kent was born in Bridlington, Yorkshire, and baptised, on 1 January 1686, as William Cant.[1]

Kent's career began as a sign and coach painter who was encouraged to study art, design and architecture by his employer. A group of Yorkshire gentlemen sent Kent for a period of study in Rome, and he set sail on 22 July 1709 from Deal, Kent, arriving at Livorno on 15 October.[2] By 18 November he was in Florence, staying there until April 1710 before finally setting off for Rome. In 1713 he was awarded the second medal in the second class for painting in the annual competition run by the Accademia di San Luca for his painting of A Miracle of S. Andrea Avellino.[3] He also met several important figures including Thomas Coke, later 1st Earl of Leicester, with whom he toured Northern Italy in the summer of 1714 (a tour that led Kent to an appreciation of the architectural style of Andrea Palladio's palaces in Vicenza), and Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni in Rome, for whom he apparently painted some pictures, though no records survive. During his stay in Rome, he painted the ceiling of the church of San Giuliano dei Fiamminghi (Church of St. Julian of the Flemings) with the Apotheosis of St. Julian.[4] The most significant meeting was between Kent and Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington. Kent left Rome for the last time in the autumn of 1719, met Lord Burlington briefly at Genoa, Kent journeying on to Paris, where Lord Burlington later joined him for the final journey back to England before the end of the year.[5] As a painter, he displaced Sir James Thornhill in decorating the new staterooms at Kensington Palace, London; for Burlington, he helped to decorate Chiswick House, especially the painted ceilings,[5] and Burlington House.

Architectural works

Kent started practising as an architect relatively late, in the 1730s.[6] He is better remembered as an architect of the revived Palladian style in England.[7] Burlington gave him the task of editing The Designs of Inigo Jones... with some additional designs in the Palladian/Jonesian taste by Burlington and Kent, which appeared in 1727. As he rose through the royal architectural establishment, the Board of Works, Kent applied this style to several public buildings in London, for which Burlington's patronage secured him the commissions: the Royal Mews at Charing Cross (1731–33, demolished in 1830), the Treasury buildings in Whitehall (1733–37), and the Horse Guards building in Whitehall (designed shortly before his death and built 1750–1759). These neo-antique buildings were inspired as much by the architecture of Raphael and Giulio Romano as by Palladio.[8]

In country house building, major commissions for Kent were designing the interiors of Houghton Hall (c.1725–35), recently built by Colen Campbell for Sir Robert Walpole, but at Holkham Hall the most complete embodiment of Palladian ideals is still to be found; there Kent collaborated with Thomas Coke, the other "architect earl", and had for an assistant Matthew Brettingham, whose own architecture would carry Palladian ideals into the next generation. Walpole's son Horace described Kent as below mediocrity as a painter, a restorer of science as an architect and the father of modern gardening and inventor of an art.[9]

A theatrically Baroque staircase and parade rooms in London, at 44 Berkeley Square, are also notable. Kent's domed pavilions were erected at Badminton House and at Euston Hall.

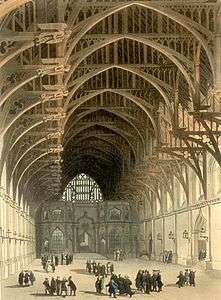

Kent could provide sympathetic Gothic designs, free of serious antiquarian tendencies, when the context called; he worked on the Gothic screens in Westminster Hall and Gloucester Cathedral.

He worked on the house at 22 Arlington Street in St. James's, a district of the City of Westminster in central London from 1743, when it was commissioned by the newly elevated Prime Minister, Henry Pelham. When Kent died, the work was completed by Stephen Wright.[10]

Landscape architect

As a landscape designer, Kent was one of the originators of the English landscape garden, a style of "natural" gardening that revolutionised the laying out of gardens and estates. His projects included Chiswick House,[11] Stowe, Buckinghamshire, from about 1730 onwards, designs for Alexander Pope's villa garden at Twickenham, for Queen Caroline at Richmond, and notably at Rousham House, Oxfordshire, where he created a sequence of Arcadian set-pieces punctuated with temples, cascades, grottoes, Palladian bridges and exedra, opening the field for the larger scale achievements of Capability Brown in the following generation. Smaller Kent works can be found at Shotover Park, Oxfordshire, including a faux Gothic eyecatcher and a domed pavilion. His all-but-lost gardens at Claremont, Surrey, have recently been restored. It is often said that he was not above planting dead trees to create the mood he required.[12]

Kent's only real downfall was said to be his lack of horticultural knowledge and technical skill[13] (which people like Charles Bridgeman possessed – whose impact on Kent is often underestimated),[14] but his naturalistic style of design was his major contribution to the history of landscape design.[15] Claremont, Stowe, and Rousham are places where their joint efforts can be viewed. Stowe and Rousham are Kent's most famous works. At the latter, Kent elaborated on Bridgeman's 1720s design for the property, adding walls and arches to catch the viewer's eye. At Stowe, Kent used his Italian experience, particularly with the Palladian Bridge. At both sites Kent incorporated his naturalistic approach.

Furniture designer

His stately furniture designs complemented his interiors: he designed furnishings for Hampton Court Palace (1732), Lord Burlington's Chiswick House (1729), London, Thomas Coke's Holkham Hall, Norfolk, Robert Walpole's pile at Houghton, for Devonshire House in London, and at Rousham. The royal barge he designed for Frederick, Prince of Wales can still be seen at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

In his own age, Kent's fame and popularity were so great that he was employed to give designs for all things, even for ladies' birthday dresses, of which he could know nothing and which he decorated with the five classical orders of architecture. These and other absurdities drew upon him the satire of William Hogarth who, in October 1725, produced a Burlesque on Kent's Altarpiece at St. Clement Danes.

Walpole tribute

According to Horace Walpole, Kent "was a painter, an architect, and the father of modern gardening. In the first character he was below mediocrity; in the second, he was a restorer of the science; in the last, an original, and the inventor of an art that realizes painting and improves nature. Mahomet imagined an elysium, Kent created many."

List of works

Domestic work

- Wanstead House, (designed by Colen Campbell) interior decoration (1721–24)

- Burlington House, London interior decoration (c.1727)

- Chiswick House, London, interiors and furniture (c.1726–29)

- Houghton Hall, interiors and furniture (c.1726–31) & stables (c.1733-5)

- Ditchley, Oxfordshire, (designed by James Gibbs) interiors (c.1726)

- Sherborne House, Gloucestershire, furniture designs (1728)

- Stowe House, interiors and garden buildings (c.1730 to 1748)

- Alexander Pope's Villa, designs for garden buildings (c.1730) demolished

- Richmond Gardens, garden buildings 1730–35, demolished

- Stanwick Park (ascribed), remodelled and interiors (c.1730–40)

- Raynham Hall, interiors and furniture (c.1731)

- Kew House, (1731–35) demolished 1802

- Esher Place, the wings (c.1733) demolished

- Shotover House, Obelisk, Octagonal & Gothic temples, (1733)

- Holkham Hall, with Earl of Burlington & Earl of Leicester executed by Matthew Brettingham (1734–1765)

- Devonshire House including furniture, (1734–35), demolished 1924-5

- Easton Neston, designed fireplaces (1735)

- Aske Hall (ascribed), Gothic temple, (1735)

- Claremont Garden, garden buildings, (1738), only the domed temple on the island in the lake survives

- Rousham House, addition of wings and landscaping of the gardens & garden buildings (1738–41)

- Badminton House, remodelling of the north front & Worcester Lodge, (c.1740)

- 22 Arlington Street, London, (1741–50), completed after Kent's death by Stephen Wright

- 44 Berkeley Square, London (1742–44)

- 16 St. James Place, London early (1740s) demolished 1899–1900

- Oatlands Palace, garden building (c.1745), demolished

- Euston Hall, Suffolk (1746)

- Wakefield Lodge, Northamptonshire (c.1748–50)

Temple of Venus, Stowe

Temple of Venus, Stowe Temple of British Worthies, Stowe

Temple of British Worthies, Stowe The Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe

The Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe Holkham Hall North Front

Holkham Hall North Front Holkham hall Marble Hall

Holkham hall Marble Hall Obelisk, Holkham Hall

Obelisk, Holkham Hall Triumphal Arch, Holkham Hall

Triumphal Arch, Holkham Hall Badminton House

Badminton House.jpg) Worcester Lodge, Badminton House

Worcester Lodge, Badminton House- Chiswick House The Gallery

Dome of Saloon, Chiswick House

Dome of Saloon, Chiswick House- Saloon, Chiswick House

Bedroom, Chiswick House

Bedroom, Chiswick House- Chiswick House Table

Chiswick House Ceiling of Blue Velvet Room

Chiswick House Ceiling of Blue Velvet Room- Chiswick House Gardens

- Chiswick House Gardens

Temple, Chiswick House

Temple, Chiswick House Chiswick House Gardens

Chiswick House Gardens Rousham Cascade

Rousham Cascade Eyecatcher, Rousham

Eyecatcher, Rousham 'Praeneste', Rousham

'Praeneste', Rousham Houghton Hall Stableyard

Houghton Hall Stableyard Temple Shotover House

Temple Shotover House Temple Euston Park

Temple Euston Park- Devonshire House, London

Public buildings & royal commissions

- Chiesa di San Giuliano dei Fiamminghi, painted ceiling (c.1717)

- York Minster, marble pavement (1731–35)

- Royal Mews, (1731–33) demolished 1830

- Royal State Barge, (1732)

- Hampton Court Palace, gateway in Clock Court & rooms for the Duke of Cumberland, (1732)

- Kensington Palace, interiors, including Cupola Room and several murals and painted ceilings (1733–35)

- former Treasury building Whitehall, (1733–37)

- St James's Palace, the library (1736–37), demolished

- Westminster Hall, Gothic screen enclosing law courts (1738–39), demolished c.1825

- York Minster, Gothic pulpit and choir furniture (1741), removed

- Gloucester Cathedral, Gothic choir-screen (1741), removed 1820

- Horse Guards, (1750–59)

Painted Ceiling Chiesa di San Giuliano dei Fiamminghi Rome, The Apotheosis of St Julian 1717

Painted Ceiling Chiesa di San Giuliano dei Fiamminghi Rome, The Apotheosis of St Julian 1717 Royal Mews

Royal Mews Horse Guards

Horse Guards Horse Guards

Horse Guards Horse Guards

Horse Guards Plan, Horse Guards

Plan, Horse Guards Horse Guards Parade, Kent's Treasury is the stone building just beyond the Horse Guards building

Horse Guards Parade, Kent's Treasury is the stone building just beyond the Horse Guards building Former Treasury Building, on left

Former Treasury Building, on left Gateway (on right), Clock Court, Hampton Court Palace

Gateway (on right), Clock Court, Hampton Court Palace Kensington Palace Cupola Room

Kensington Palace Cupola Room_after_Richard_CATTERMOLE_(1795-1858).jpg) Kensington Palace Cupola Room

Kensington Palace Cupola Room painted ceiling, Presence Chamber, Kensington Palace

painted ceiling, Presence Chamber, Kensington Palace mural & ceiling, Great Staircase, Kensington Palace

mural & ceiling, Great Staircase, Kensington Palace Westminster Hall, with Kent's screen in place

Westminster Hall, with Kent's screen in place- Choir York Minster, showing Kent's black & white marble floor

Church memorials

- Chester Cathedral, to John & Thomas Wainwright

- Henry VII Lady Chapel, to George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (1730)

- York Minster, to Thomas Watson Wentworth (1731)

- Westminster Abbey to Sir Isaac Newton, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack (1731)

- Kirkthorpe church, to Thomas & Catherine Stringer (1731–32)

- Blenheim Palace Chapel, to John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack (1733)

- Westminster Abbey, to James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope (1733)

- Westminster Abbey, to William Shakespeare, sculpted by Peter Scheemakers (1740)

- Ashby-de-la-Zouch, to Theophilus Hastings, 9th Earl of Huntingdon (1746)

- Chapel, Blenheim Palace, Marlborough tomb on right

Sir Isaac Newton's memorial, Westminster Abbey

Sir Isaac Newton's memorial, Westminster Abbey.jpg) Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, with the Shakespeare memorial

Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, with the Shakespeare memorial

See also

- Lancelot "Capability" Brown

References

Citations

- Harris, John (September 2004). "Kent, William (bap. 1686, d. 1748)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- See M. I. Wilson, 1984, pp. 5

- See M. I. Wilson, 1984, pp. 9–10

- Official website of the Church of St. Julian of the Flemings Archived 25 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch)

- Clegg, 1995. p. 46

- Curl, J.S. (Ed.), Oxford Dictionary of Architecture, Oxford University Press (1999), ISBN 0-19-280017-5.

- The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., Palladio and British-American Palladianism

- Sicca, Cinzia Maria, (1986) "On William Kent's Roman sources", Architectural History, vol. 29, 1986, pp. 134–147.

- Morel, Thierry (2013). "Houghton Revisited: An Introduction". Houghton Revisited. Royal Academy of Arts. p. 36.

- Historic England. "Location Wimbourne House, 22, Arlington Street SW1 (1066498)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Clegg, 1995. p. 47

- Rotherham, Ian D. (2013). Trees, Forested Landscapes and Grazing Animals: A European Perspective on Woodlands and Grazed Treescapes. Oxon: Routledge. p. 387. ISBN 0415626110. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- "Development of the English Garden". Colorado State University. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Owen, Jane. "William Kent's English landscape revolution at Rousham". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- Wrigley, Richard (2014). The Flâneur Abroad: Historical and International Perspectives. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 1443860166. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

Sources

- Chaney, Edward (2000) The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed., 2000. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_evolution_of_the_grand_tour.html?id=rYB_HYPsa8gC

- Clegg, Gillian (1995). Chiswick Past. Historical Publications.

- Colvin, Howard, (1995) A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840. 3rd ed., 1995, s.v. "Kent, William"

- Hunt, John Dixon, (1986; 1996) Garden and Grove: The Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination, 1600–1750, London, Dent; London and Philadelphia. ISBN 0-460-04681-0

- Hunt, John Dixon, (1987) William Kent, Landscape garden designer: An Assessment and Catalogue of his designs. London, Zwemmer.

- Jourdain, M., (1948) The Work of William Kent: Artist, Painter, Designer and Landscape Gardener. London, Country Life.

- Mowl, Timothy, (2006) William Kent: Architect, Designer, Opportunist. London, Jonathan Cape.

- Newton, N., (1971) Design of the land. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Ross, David, (2000) William Kent. Britain Express, 1–2. Retrieved 26 September 2004, from britainexpress.com

- Rogers, E., (2001) Landscape design a cultural and architectural history. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Sicca, Cinzia Maria, (1986) "On William Kent's Roman sources", Architectural History, vol. 29, 1986, pp. 134–147.

- Wilson, Michael I., (1984) William Kent: Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685–1748. London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley, Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-9983-5.

Further reading

- Amherst, Alicia (1896). A History of Gardening in England (2nd ed.). London – via Haithi Trust.

- Blomfield, Sir F. Reginald; Thomas, Inigo, Illustrator (1972) [1901]. The Formal Garden in England, 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan and Co.

- Clifford, Derek (1967). A History of Garden Design (2nd ed.). New York: Praeger.

- Gothein, Marie-Luise Schröeter (1863–1931); Wright, Walter P. (1864–1940); Archer-Hind, Laura; Alden Hopkins Collection (1928) [1910]. History of Garden Art. 2. London & Toronto, New York: J. M. Dent; 1928 Dutton. ISBN 978-3-424-00935-4. 945 pages Publisher: Hacker Art Books; Facsimile edition (June 1972) ISBN 0-87817-008-1; ISBN 978-0-87817-008-1.

- Gothein, Marie. Geschichte der Gartenkunst. München: Diederichs, 1988 ISBN 978-3-424-00935-4.

- Hadfield, Miles (1960). Gardening in Britain. Newton, Mass: C. T. Branford.

- Hussey, Christopher (1967). English Gardens and Landscapes, 1700–1750. Country Life.

- Hyams, Edward S.; Smith, Edwin, photos (1964). The English Garden. New York: H.N. Abrams.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Kent. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Kent, William. |

- Short biography on gardenvisit.com

- Short biography on britainexpress.com

- Design examples on furniturestyles.net

- 14 paintings by or after William Kent at the Art UK site

| Court offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Godfrey Kneller |

Principal Painter in Ordinary to the King 1723–1748 |

Succeeded by John Shackleton |