Megabat

Megabats constitute the family Pteropodidae of the order Chiroptera (bats). They are also called fruit bats, Old World fruit bats, or—especially the genera Acerodon and Pteropus—flying foxes. They are the only member of the superfamily Pteropodoidea, which is one of two superfamilies in the suborder Yinpterochiroptera. Internal divisions of Pteropodidae have varied since subfamilies were first proposed in 1917. From three subfamilies in the 1917 classification, six are now recognized, along with various tribes. As of 2018, 197 species of megabat had been described.

| Megabat | |

|---|---|

| |

| A colony of little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Superfamily: | Pteropodoidea |

| Family: | Pteropodidae Gray, 1821 |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of megabats | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pteropidae (Gray, 1821)[1] | |

The understanding of the evolution of megabats has been determined primarily by genetic data, as the fossil record for this family is the most fragmented of all bats. They likely evolved in Australasia, with the common ancestor of all living pteropodids existing approximately 31 million years ago. Many of their lineages probably originated in Melanesia, then dispersed over time to mainland Asia, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Today, they are found in tropical and subtropical areas of Eurasia, Africa, and Oceania.

The megabat family contains the largest bat species, with individuals of some species weighing up to 1.45 kg (3.2 lb) and having wingspans up to 1.7 m (5.6 ft). Not all megabats are large-bodied; nearly a third of all species weigh less than 50 g (1.8 oz). They can be differentiated from other bats due to their dog-like faces, clawed second digits, and reduced uropatagium. Only members of one genus, Notopteris, have tails. Megabats have several adaptations for flight, including rapid oxygen consumption, the ability to sustain heart rates of more than 700 beats per minute, and large lung volumes.

Most megabats are nocturnal or crepuscular, although a few species are active during the daytime. During the period of inactivity, they roost in trees or caves. Members of some species roost alone, while others form colonies of up to a million individuals. During the period of activity, they use flight to travel to food resources. With few exceptions, they are unable to echolocate, relying instead on keen senses of sight and smell to navigate and locate food. Most species are primarily frugivorous and several are nectarivorous. Other less common food resources include leaves, pollen, twigs, and bark.

They reach sexual maturity slowly and have a low reproductive output. Most species have one offspring at a time after a pregnancy of four to six months. This low reproductive output means that after a population loss their numbers are slow to rebound. A quarter of all species are listed as threatened, mainly due to habitat destruction and overhunting. Megabats are a popular food source in some areas, leading to population declines and extinction. They are also of interest to those involved in public health as they are natural reservoirs of several viruses that can affect humans.

Taxonomy and evolution

Taxonomic history

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internal relationships of African Pteropodidae based on combined evidence of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. One species each of Pteropodinae, Nyctimeninae, and Cynopterinae, which are not found in Africa, were included as outgroups.[2] |

The family Pteropodidae was first described in 1821 by British zoologist John Edward Gray. He named the family "Pteropidae" (after the genus Pteropus) and placed it within the now-defunct order Fructivorae.[3] Fructivorae contained one other family, the now-defunct Cephalotidae, containing one genus, Cephalotes[3] (now recognized as a synonym of Dobsonia).[4] Gray's spelling was possibly based on a misunderstanding of the suffix of "Pteropus".[5] "Pteropus" comes from Ancient Greek "pterón" meaning "wing" and "poús" meaning "foot".[6] The Greek word pous of Pteropus is from the stem word pod-; therefore, Latinizing Pteropus correctly results in the prefix "Pteropod-".[7]:230 French biologist Charles Lucien Bonaparte was the first to use the corrected spelling Pteropodidae in 1838.[7]:230

In 1875, Irish zoologist George Edward Dobson was the first to split the order Chiroptera (bats) into two suborders: Megachiroptera (sometimes listed as Macrochiroptera) and Microchiroptera, which are commonly abbreviated to megabats and microbats.[8] Dobson selected these names to allude to the body size differences of the two groups, with many fruit-eating bats being larger than insect-eating bats. Pteropodidae was the only family he included within Megachiroptera.[5][8]

A 2001 study found that the dichotomy of megabats and microbats did not accurately reflect their evolutionary relationships. Instead of Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera, the study's authors proposed the new suborders Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera.[9] This classification scheme has been verified several times subsequently and remains widely supported as of 2019.[10][11][12][13] Since 2005, this suborder has alternatively been called "Pteropodiformes".[7]:520–521 Yinpterochiroptera contained species formerly included in Megachiroptera (all of Pteropodidae), as well as several families formerly included in Microchiroptera: Megadermatidae, Rhinolophidae, Nycteridae, Craseonycteridae, and Rhinopomatidae.[9] Two superfamilies comprise Yinpterochiroptera: Rhinolophoidea—containing the above families formerly in Microchiroptera—and Pteropodoidea, which only contains Pteropodidae.[14]

In 1917, Danish mammalogist Knud Andersen divided Pteropodidae into three subfamilies: Macroglossinae, Pteropinae (corrected to Pteropodinae), and Harpyionycterinae.[15]:496 A 1995 study found that Macroglossinae as previously defined, containing the genera Eonycteris, Notopteris, Macroglossus, Syconycteris, Melonycteris, and Megaloglossus, was paraphyletic, meaning that the subfamily did not group all the descendants of a common ancestor.[16]:214 Subsequent publications consider Macroglossini as a tribe within Pteropodinae that contains only Macroglossus and Syconycteris.[17][18] Eonycteris and Melonycteris are within other tribes in Pteropodinae,[2][18] Megaloglossus was placed in the tribe Myonycterini of the subfamily Rousettinae, and Notopteris is of uncertain placement.[18]

Other subfamilies and tribes within Pteropodidae have also undergone changes since Andersen's 1917 publication.[18] In 1997, the pteropodids were classified into six subfamilies and nine tribes based on their morphology, or physical characteristics.[18] A 2011 genetic study concluded that some of these subfamilies were paraphyletic and therefore they did not accurately depict the relationships among megabat species. Three of the subfamilies proposed in 1997 based on morphology received support: Cynopterinae, Harpyionycterinae, and Nyctimeninae. The other three clades recovered in this study consisted of Macroglossini, Epomophorinae + Rousettini, and Pteropodini + Melonycteris.[18] A 2016 genetic study focused only on African pteropodids (Harpyionycterinae, Rousettinae, and Epomophorinae) also challenged the 1997 classification. All species formerly included in Epomophorinae were moved to Rousettinae, which was subdivided into additional tribes. The genus Eidolon, formerly in the tribe Rousettini of Rousettinae, was moved to its own subfamily, Eidolinae.[2]

In 1984, an additional pteropodid subfamily, Propottininae, was proposed, representing one extinct species described from a fossil discovered in Africa, Propotto leakeyi.[19] In 2018 the fossils were reexamined and determined to represent a lemur.[20] As of 2018, there were 197 described species of megabat,[21] around a third of which are flying foxes of the genus Pteropus.[22]

Evolutionary history

Fossil record and divergence times

The fossil record for pteropodid bats is the most incomplete of any bat family. Several factors could explain why so few pteropodid fossils have been discovered: tropical regions where their fossils might be found are undersampled relative to Europe and North America; conditions for fossilization are poor in the tropics, which could lead to fewer fossils overall; and fossils may have been created, but they may have been destroyed by subsequent geological activity.[23] It is estimated that more than 98% of pteropodid fossil history is missing.[24] Even without fossils, the age and divergence times of the family can still be estimated by using computational phylogenetics. Pteropodidae split from the superfamily Rhinolophoidea (which contains all the other families of the suborder Yinpterochiroptera) approximately 58 Mya (million years ago).[24] The ancestor of the crown group of Pteropodidae, or all living species, lived approximately 31 Mya.[25]

Biogeography

The family Pteropodidae likely originated in Australasia based on biogeographic reconstructions.[2] Other biogeographic analyses have suggested that the Melanesian Islands, including New Guinea, are a plausible candidate for the origin of most megabat subfamilies, with the exception of Cynopterinae;[18] the cynopterines likely originated on the Sunda Shelf based on results of a Weighted Ancestral Area Analysis of six nuclear and mitochondrial genes.[25] From these regions, pteropodids colonized other areas, including continental Asia and Africa. Megabats reached Africa in at least four distinct events. The four proposed events are represented by (1) Scotonycteris, (2) Rousettus, (3) Scotonycterini, and (4) the "endemic Africa clade", which includes Stenonycterini, Plerotini, Myonycterini, and Epomophorini, according to a 2016 study. It is unknown when megabats reached Africa, but several tribes (Scotonycterini, Stenonycterini, Plerotini, Myonycterini, and Epomophorini) were present by the Late Miocene. How megabats reached Africa is also unknown. It has been proposed that they could have arrived via the Middle East before it became more arid at the end of the Miocene. Conversely, they could have reached the continent via the Gomphotherium land bridge, which connected Africa and the Arabian Peninsula to Eurasia. The genus Pteropus (flying foxes), which is not found on mainland Africa, is proposed to have dispersed from Melanesia via island hopping across the Indian Ocean;[26] this is less likely for other megabat genera, which have smaller body sizes and thus have more limited flight capabilities.[2]

Echolocation

Megabats are the only family of bats incapable of laryngeal echolocation. It is unclear whether the common ancestor of all bats was capable of echolocation, and thus echolocation was lost in the megabat lineage, or multiple bat lineages independently evolved the ability to echolocate (the superfamily Rhinolophoidea and the suborder Yangochiroptera). This unknown element of bat evolution has been called a "grand challenge in biology".[27] A 2017 study of bat ontogeny (embryonic development) found evidence that megabat embryos at first have large, developed cochlea similar to echolocating microbats, though at birth they have small cochlea similar to non-echolocating mammals. This evidence supports that laryngeal echolocation evolved once among bats, and was lost in pteropodids, rather than evolving twice independently.[28] Megabats in the genus Rousettus are capable of primitive echolocation through clicking their tongues.[29] Some species—the cave nectar bat (Eonycteris spelaea), lesser short-nosed fruit bat (Cynopterus brachyotis), and the long-tongued fruit bat (Macroglossus sobrinus)— have been shown to create clicks similar to those of echolocating bats using their wings.[30]

Both echolocation and flight are energetically expensive processes.[31] Echolocating bats couple sound production with the mechanisms engaged for flight, allowing them to reduce the additional energy burden of echolocation. Instead of pressurizing a bolus of air for the production of sound, laryngeally echolocating bats likely use the force of the downbeat of their wings to pressurize the air, cutting energetic costs by synchronizing wingbeats and echolocation.[32] The loss of echolocation (or conversely, the lack of its evolution) may be due to the uncoupling of flight and echolocation in megabats.[33] The larger average body size of megabats compared to echolocating bats[34] suggests a larger body size disrupts the flight-echolocation coupling and made echolocation too energetically expensive to be conserved in megabats.[33]

List of genera

_(cropped).jpg)

The family Pteropodidae is divided into six subfamilies represented by 46 genera:[2][18]

Family Pteropodidae

- subfamily Cynopterinae[18]

- genus Aethalops – pygmy fruit bats

- genus Alionycteris

- genus Balionycteris

- genus Chironax

- genus Cynopterus – dog-faced fruit bats or short-nosed fruit bats

- genus Dyacopterus – Dayak fruit bats

- genus Haplonycteris

- genus Latidens

- genus Megaerops

- genus Otopteropus

- genus Penthetor

- genus Ptenochirus – musky fruit bats

- genus Sphaerias

- genus Thoopterus

- subfamily Eidolinae[2]

- genus Eidolon – straw-coloured fruit bats

- subfamily Harpiyonycterinae[2]

- genus Aproteles

- genus Boneia

- genus Dobsonia – naked-backed fruit bats

- genus Harpyionycteris

- subfamily Nyctimeninae[18]

- genus Nyctimene – tube-nosed fruit bats

- genus Paranyctimene

- subfamily Pteropodinae

- genus Melonycteris[18]

- tribe Pteropodini[18]

- genus Acerodon

- genus Pteralopex

- genus Pteropus – flying foxes

- genus Styloctenium

- subfamily Rousettinae

- tribe Eonycterini[2]

- genus Eonycteris – dawn fruit bats

- tribe Epomophorini[2][18]

- genus Epomophorus – epauletted fruit bats

- genus Epomops – epauletted bats

- genus Hypsignathus

- genus Micropteropus – dwarf epauletted bats

- genus Nanonycteris

- tribe Myonycterini[2]

- genus Megaloglossus

- genus Myonycteris – little collared fruit bats

- tribe Plerotini[2]

- genus Plerotes

- tribe Rousettini[2]

- genus Rousettus – rousette fruit bats

- tribe Scotonycterini[2]

- genus Casinycteris

- genus Scotonycteris

- tribe Stenonycterini[2]

- genus Stenonycteris

- tribe Eonycterini[2]

- Incertae sedis

- genus Notopteris – long-tailed fruit bats[18]

- genus Mirimiri[18]

- genus Neopteryx[18]

- genus Desmalopex[18]

- genus †Turkanycteris[35]

- tribe Macroglossini[18]

- genus Macroglossus – long-tongued fruit bats

- genus Syconycteris – blossom bats

Description

Appearance

Megabats are so called for their larger weight and size; the largest, the great flying fox (Pteropus neohibernicus) weighs up to 1.6 kg (3.5 lb),[36] Two subspecies are recognized:[37] with wingspans reaching up to 1.7 m (5.6 ft).[38] Despite the fact that body size was a defining characteristic that Dobson used to separate microbats and megabats, not all species of megabat are larger than microbats; the spotted-winged fruit bat (Balionycteris maculata), a megabat, weighs only 14.2 g (0.50 oz).[39] The flying foxes of Pteropus and Acerodon are often taken as exemplars of the whole family in terms of body size. In reality, these genera are outliers, creating a misconception of the true size of most megabat species.[5] A 2004 review stated that 28% of megabat species weigh less than 50 g (1.8 oz).[39]

Megabats can be distinguished from microbats in appearance by their dog-like faces, by the presence of claws on the second digit (see Megabat#Postcrania), and by their simple ears.[40] The simple appearance of the ear is due in part to the lack of tragi (cartilage flaps projecting in front of the ear canal), which are found in many microbat species. Megabats of the genus Nyctimene appear less dog-like, with shorter faces and tubular nostrils.[41] A 2011 study of 167 megabat species found that while the majority (63%) have fur that is a uniform color, other patterns are seen in this family. These include countershading in four percent of species, a neck band or mantle in five percent of species, stripes in ten percent of species, and spots in nineteen percent of species.[42]

Unlike microbats, megabats have a greatly reduced uropatagium, which is an expanse of flight membrane that runs between the hind limbs.[43] Additionally, the tail is absent or greatly reduced,[41] with the exception of Notopteris species, which have a long tail.[44] Most megabat wings insert laterally (attach to the body directly at the sides). In Dobsonia species, the wings attach nearer the spine, giving them the common name of "bare-backed" or "naked-backed" fruit bats.[43]

Skeleton

Skull and dentition

Megabats have large orbits, which are bordered by well-developed postorbital processes posteriorly. The postorbital processes sometimes join to form the postorbital bar. The snout is simple in appearance and not highly modified, as is seen in other bat families.[45] The length of the snout varies among genera. The premaxilla is well-developed and usually free,[4] meaning that it is not fused with the maxilla; instead, it articulates with the maxilla via ligaments, making it freely movable.[46][47] The premaxilla always lack a palatal branch.[4] In species with a longer snout, the skull is usually arched. In genera with shorter faces (Penthetor, Nyctimene, Dobsonia, and Myonycteris), the skull has little to no bending.[48]

The number of teeth varies among megabat species; totals for various species range from 24 to 34. All megabats have two or four each of upper and lower incisors, with the exception Bulmer's fruit bat (Aproteles bulmerae), which completely lacks incisors,[49] and the São Tomé collared fruit bat (Myonycteris brachycephala), which has two upper and three lower incisors.[50] This makes it the only mammal species with an asymmetrical dental formula.[50]

All species have two upper and lower canine teeth. The number of premolars is variable, with four or six each of upper and lower premolars. The first upper and lower molars are always present, meaning that all megabats have at least four molars. The remaining molars may be present, present but reduced, or absent.[49] Megabat molars and premolars are simplified, with a reduction in the cusps and ridges resulting in a more flattened crown.[51]

Like most mammals, megabats are diphyodont, meaning that the young have a set of deciduous teeth (milk teeth) that falls out and is replaced by permanent teeth. For most species, there are 20 deciduous teeth. As is typical for mammals,[52] the deciduous set does not include molars.[51]

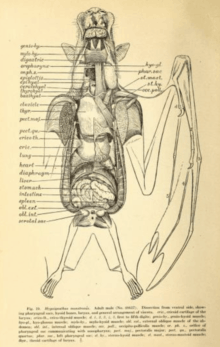

Postcrania

The scapulae (shoulder blades) of megabats have been described as the most primitive of any chiropteran family.[51] The shoulder is overall of simple construction, but has some specialized features. The primitive insertion of the omohyoid muscle from the clavicle (collarbone) to the scapula is laterally displaced (more towards the side of the body)—a feature also seen in the Phyllostomidae. The shoulder also has a well-developed system of muscular slips (narrow bands of muscle that augment larger muscles) that anchor the tendon of the occipitopollicalis muscle (muscle in bats that runs from base of neck to the base of the thumb)[43] to the skin.[41]

While microbats only have claws on the thumbs of their forelimbs, most megabats have a clawed second digit as well;[51] only Eonycteris, Dobsonia, Notopteris, and Neopteryx lack the second claw.[53] The first digit is the shortest, while the third digit is the longest. The second digit is incapable of flexion.[51] Megabats' thumbs are longer relative to their forelimbs than those of microbats.[43]

Megabats' hindlimbs have the same skeletal components as humans. Most megabat species have an additional structure called the calcar, a cartilage spur arising from the calcaneus.[54] Some authors alternately refer to this structure as the uropatagial spur to differentiate it from microbats' calcars, which are structured differently. The structure exists to stabilize the uropatagium, allowing bats to adjust the camber of the membrane during flight. Megabats lacking the calcar or spur include Notopteris, Syconycteris, and Harpyionycteris.[55] The entire leg is rotated at the hip compared to normal mammal orientation, meaning that the knees face posteriorly. All five digits of the foot flex in the direction of the sagittal plane, with no digit capable of flexing in the opposite direction, as in the feet of perching birds.[54]

Internal systems

Flight is very energetically expensive, requiring several adaptations to the cardiovascular system. During flight, bats can raise their oxygen consumption by twenty times or more for sustained periods; human athletes can achieve an increase of a factor of twenty for a few minutes at most.[56] A 1994 study of the straw-coloured fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) and hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus) found a mean respiratory exchange ratio (carbon dioxide produced:oxygen used) of approximately 0.78. Among these two species, the gray-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) and the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus), maximum heart rates in flight varied between 476 beats per minute (gray-headed flying fox) and 728 beats per minute (Egyptian fruit bat). The maximum number of breaths per minute ranged from 163 (gray-headed flying fox) to 316 (straw-colored fruit bat).[57] Additionally, megabats have exceptionally large lung volumes relative to their sizes. While terrestrial mammals such as shrews have a lung volume of 0.03 cm3 per gram of body weight (0.05 in3 per ounce of body weight), species such as the Wahlberg's epauletted fruit bat (Epomophorus wahlbergi) have lung volumes 4.3 times greater at 0.13 cm3 per gram (0.22 in3 per ounce).[56]

Megabats have rapid digestive systems, with a gut transit time of half an hour or less.[41] The digestive system is structured to a herbivorous diet sometimes restricted to soft fruit or nectar.[58] The length of the digestive system is short for a herbivore (as well as shorter than those of insectivorous microchiropterans),[58] as the fibrous content is mostly separated by the action of the palate, tongue, and teeth, and then discarded.[58] Many megabats have U-shaped stomachs. There is no distinct difference between the small and large intestine, nor a distinct beginning of the rectum. They have very high densities of intestinal microvilli, which creates a large surface area for the absorption of nutrients.[59]

Biology and ecology

Genome size

Like all bats, megabats have much smaller genomes than other mammals. A 2009 study of 43 megabat species found that their genomes ranged from 1.86 picograms (pg) in the straw-colored fruit bat to 2.51 pg in Lyle's flying fox (Pteropus lylei). All values were much lower than the mammalian average of 3.5 pg. Megabats have even smaller genomes than microbats, with a mean weight of 2.20 pg compared to 2.58 pg. It was speculated that this difference could be related to the fact that the megabat lineage has experienced an extinction of the LINE1—a type of long interspersed nuclear element. LINE1 constitutes 15–20% of the human genome and is considered the most prevalent long interspersed nuclear element among mammals.[60]

Senses

Sight

With very few exceptions, megabats do not echolocate, and therefore rely on sight and smell to navigate.[61] They have large eyes positioned at the front of their heads.[62] These are larger than those of the common ancestor of all bats, with one study suggesting a trend of increasing eye size among pteropodids. A study that examined the eyes of 18 megabat species determined that the common blossom bat (Syconycteris australis) had the smallest eyes at a diameter of 5.03 mm (0.198 in), while the largest eyes were those of large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus) at 12.34 mm (0.486 in) in diameter.[63] Megabat irises are usually brown, but they can be red or orange, as in Desmalopex, Mirimiri, Pteralopex, and some Pteropus.[64]

At high brightness levels, megabat visual acuity is poorer than that of humans; at low brightness it is superior.[62] One study that examined the eyes of some Rousettus, Epomophorus, Eidolon, and Pteropus species determined that the first three genera possess a tapetum lucidum, a reflective structure in the eyes that improves vision at low light levels, while the Pteropus species do not.[61] All species examined had retinae with both rod cells and cone cells, but only the Pteropus species had S-cones, which detect the shortest wavelengths of light; because the spectral tuning of the opsins was not discernible, it is unclear whether the S-cones of Pteropus species detect blue or ultraviolet light. Pteropus bats are dichromatic, possessing two kinds of cone cells. The other three genera, with their lack of S-cones, are monochromatic, unable to see color. All genera had very high densities of rod cells, resulting in high sensitivity to light, which corresponds with their nocturnal activity patterns. In Pteropus and Rousettus, measured rod cell densities were 350,000–800,000 per square millimeter, equal to or exceeding other nocturnal or crepuscular animals such as the house mouse, domestic cat, and domestic rabbit.[61]

Smell

Megabats use smell to find food sources like fruit and nectar.[65] They have keen senses of smell that rival that of the domestic dog.[66] Tube-nosed fruit bats such as the eastern tube-nosed bat (Nyctimene robinsoni) have stereo olfaction, meaning they are able to map and follow odor plumes three-dimensionally.[66] Along with most (or perhaps all) other bat species, megabats mothers and offspring also use scent to recognize each other, as well as for recognition of individuals.[65] In flying foxes, males have enlarged androgen-sensitive sebaceous glands on their shoulders they use for scent-marking their territories, particularly during the mating season. The secretions of these glands vary by species—of the 65 chemical compounds isolated from the glands of four species, no compound was found in all species.[67] Males also engage in urine washing, or coating themselves in their own urine.[67][68]

Taste

Megabats possess the TAS1R2 gene, meaning they have the ability to detect sweetness in foods. This gene is present among all bats except vampire bats. Like all other bats, megabats cannot taste umami, due to the absence of the TAS1R1 gene. Among other mammals, only giant pandas have been shown to lack this gene.[65] Megabats also have multiple TAS2R genes, indicating that they can taste bitterness.[69]

Reproduction and life cycle

Megabats, like all bats, are long-lived relative to their size for mammals. Some captive megabats have had lifespans exceeding thirty years.[53] Relative to their sizes, megabats have low reproductive outputs and delayed sexual maturity, with females of most species not giving birth until the age of one or two.[70]:6 Some megabats appear to be able to breed throughout the year, but the majority of species are likely seasonal breeders.[53] Mating occurs at the roost.[71] Gestation length is variable,[72] but is four to six months in most species. Different species of megabats have reproductive adaptations that lengthen the period between copulation and giving birth. Some species such as the straw-coloured fruit bat have the reproductive adaptation of delayed implantation, meaning that copulation occurs in June or July, but the zygote does not implant into the uterine wall until months later in November.[70]:6 The Fischer's pygmy fruit bat (Haplonycteris fischeri), with the adaptation of post-implantation delay, has the longest gestation length of any bat species, at up to 11.5 months.[72] The post-implantation delay means that development of the embryo is suspended for up to eight months after implantation in the uterine wall, which is responsible for its very long pregnancies.[70]:6 Shorter gestation lengths are found in the greater short-nosed fruit bat (Cynopterus sphinx) with a period of three months.[73]

The litter size of all megabats is usually one.[70]:6 There are scarce records of twins in the following species: Madagascan flying fox (Pteropus rufus), Dobson's epauletted fruit bat (Epomops dobsoni), the gray-headed flying fox, the black flying fox (Pteropus alecto), the spectacled flying fox (Pteropus conspicillatus),[74] the greater short-nosed fruit bat,[75] Peters's epauletted fruit bat (Epomophorus crypturus), the hammer-headed bat, the straw-colored fruit bat, the little collared fruit bat (Myonycteris torquata), the Egyptian fruit bat, and Leschenault's rousette (Rousettus leschenaultii).[76]:85–87 In the cases of twins, it is rare that both offspring survive.[74] Because megabats, like all bats, have low reproductive rates, their populations are slow to recover from declines.[77]

At birth, megabat offspring are, on average, 17.5% of their mother's post-partum weight. This is the smallest offspring-to-mother ratio for any bat family; across all bats, newborns are 22.3% of their mother's post-partum weight. Megabat offspring are not easily categorized into the traditional categories of altricial (helpless at birth) or precocial (capable at birth). Species such as the greater short-nosed fruit bat are born with their eyes open (a sign of precocial offspring), whereas the Egyptian fruit bat offspring's eyes do not open until nine days after birth (a sign of altricial offspring).[78]

As with nearly all bat species, males do not assist females in parental care.[79] The young stay with their mothers until they are weaned; how long weaning takes varies throughout the family. Megabats, like all bats, have relatively long nursing periods: offspring will nurse until they are approximately 71% of adult body mass, compared to 40% of adult body mass in non-bat mammals.[80] Species in the genus Micropteropus wean their young by seven to eight weeks of age, whereas the Indian flying fox (Pteropus medius) does not wean its young until five months of age.[76] Very unusually, male individuals of two megabat species, the Bismarck masked flying fox (Pteropus capistratus) and the Dayak fruit bat (Dyacopterus spadiceus), have been observed producing milk, but there has never been an observation of a male nursing young.[81] It is unclear if the lactation is functional and males actually nurse pups or if it is a result of stress or malnutrition.[82]

Behavior and social systems

Many megabat species are highly gregarious or social. Megabats will vocalize to communicate with each other, creating noises described as "trill-like bursts of sound",[83] honking,[84] or loud, bleat-like calls[85] in various genera. At least one species, the Egyptian fruit bat, is capable of a kind of vocal learning called vocal production learning, defined as "the ability to modify vocalizations in response to interactions with conspecifics".[86][87] Young Egyptian fruit bats are capable of acquiring a dialect by listening to their mothers, as well as other individuals in their colonies. It has been postulated that these dialect differences may result in individuals of different colonies communicating at different frequencies, for instance.[88][89]

Megabat social behavior includes using sexual behaviors for more than just reproduction. Evidence suggests that female Egyptian fruit bats take food from males in exchange for sex. Paternity tests confirmed that the males from which each female scrounged food had a greater likelihood of fathering the scrounging female's offspring.[90] Homosexual fellatio has been observed in at least one species, the Bonin flying fox (Pteropus pselaphon).[91][92] This same-sex fellatio is hypothesized to encourage colony formation of otherwise-antagonistic males in colder climates.[91][92]

Megabats are mostly nocturnal and crepuscular, though some have been observed flying during the day.[38] A few island species and subspecies are diurnal, hypothesized as a response to a lack of predators. Diurnal taxa include a subspecies of the black-eared flying fox (Pteropus melanotus natalis), the Mauritian flying fox (Pteropus niger), the Caroline flying fox (Pteropus molossinus), a subspecies of Pteropus pelagicus (P. p. insularis), and the Seychelles fruit bat (Pteropus seychellensis).[93]:9

Roosting

A 1992 summary of forty-one megabat genera noted that twenty-nine are tree-roosting genera. A further eleven genera roost in caves, and the remaining six genera roost in other kinds of sites (human structures, mines, and crevices, for example). Tree-roosting species can be solitary or highly colonial, forming aggregations of up to one million individuals. Cave-roosting species form aggregations ranging from ten individuals up to several thousand. Highly colonial species often exhibit roost fidelity, meaning that their trees or caves may be used as roosts for many years. Solitary species or those that aggregate in smaller numbers have less fidelity to their roosts.[70]:2

Diet and foraging

Most megabats are primarily frugivorous.[94] Throughout the family, a diverse array of fruit is consumed from nearly 188 plant genera.[95] Some species are also nectarivorous, meaning that they also drink nectar from flowers.[94] In Australia, Eucalyptus flowers are an especially important food source.[41] Other food resources include leaves, shoots, buds, pollen, seed pods, sap, cones, bark, and twigs.[96] They are prodigious eaters and can consume up to 2.5 times their own body weight in fruit per night.[95]

Megabats fly to roosting and foraging resources. They typically fly straight and relatively fast for bats; some species are slower with greater maneuverability. Species can commute 20–50 km (12–31 mi) in a night. Migratory species of the genera Eidolon, Pteropus, Epomophorus, Rousettus, Myonycteris, and Nanonycteris can migrate distances up to 750 km (470 mi). Most megabats have below-average aspect ratios,[97] which is measurement relating wingspan and wing area.[97]:348 Wing loading, which measures weight relative to wing area,[97]:348 is average or higher than average in megabats.[97]

Seed dispersal

Megabats play an important role in seed dispersal. As a result of their long evolutionary history, some plants have evolved characteristics compatible with bat senses, including fruits that are strongly scented, brightly colored, and prominently exposed away from foliage. The bright colors and positioning of the fruit may reflect megabats' reliance on visual cues and inability to navigate through clutter. In a study that examined the fruits of more than forty fig species, only one fig species was consumed by both birds and megabats; most species are consumed by one or the other. Bird-consumed figs are frequently red or orange, while megabat-consumed figs are often yellow or green.[98] Most seeds are excreted shortly after consumption due to a rapid gut transit time, but some seeds can remain in the gut for more than twelve hours. This heightens megabats' capacity to disperse seeds far from parent trees.[99] As highly mobile frugivores, megabats have the capacity to restore forest between isolated forest fragments by dispersing tree seeds to deforested landscapes.[100] This dispersal ability is limited to plants with small seeds that are less than 4 mm (0.16 in) in length, as seeds larger than this are not ingested.[101]

Predators and parasites

Megabats, especially those living on islands, have few native predators: species like the small flying fox (Pteropus hypomelanus) have no known natural predators.[102] Non-native predators of flying foxes include domestic cats and rats. The mangrove monitor, which is a native predator for some megabat species but an introduced predator for others, opportunistically preys on megabats, as it is a capable tree climber.[103] Another species, the brown tree snake, can seriously impact megabat populations; as a non-native predator in Guam, the snake consumes so many offspring that it reduced the recruitment of the population of the Mariana fruit bat (Pteropus mariannus) to essentially zero. The island is now considered a sink for the Mariana fruit bat, as its population there relies on bats immigrating from the nearby island of Rota to bolster it rather than successful reproduction.[104] Predators that are naturally sympatric with megabats include reptiles such as crocodilians, snakes, and large lizards, as well as birds like falcons, hawks, and owls.[70]:5 The saltwater crocodile is a known predator of megabats, based on analysis of crocodile stomach contents in northern Australia.[105] During extreme heat events, megabats like the little red flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus) must cool off and rehydrate by drinking from waterways, making them susceptible to opportunistic depredation by freshwater crocodiles.[106]

Megabats are the hosts of several parasite taxa. Known parasites include Nycteribiidae and Streblidae species ("bat flies"),[107][108] as well as mites of the genus Demodex.[109] Blood parasites of the family Haemoproteidae and intestinal nematodes of Toxocaridae also affect megabat species.[41][110]

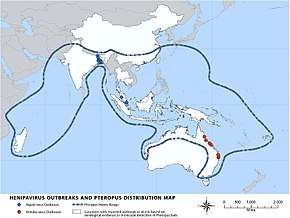

Range and habitat

Megabats are widely distributed in the tropics of the Old World, occurring throughout Africa, Asia, Australia, and throughout the islands of the Indian Ocean and Oceania.[18] As of 2013, fourteen genera of megabat are present in Africa, representing twenty-eight species. Of those twenty-eight species, twenty-four are only found in tropical or subtropical climates. The remaining four species are mostly found in the tropics, but their ranges also encompass temperate climates. In respect to habitat types, eight are exclusively or mostly found in forested habitat; nine are found in both forests and savannas; nine are found exclusively or mostly in savannas; and two are found on islands. Only one African species, the long-haired rousette (Rousettus lanosus), is found mostly in montane ecosystems, but an additional thirteen species' ranges extend into montane habitat.[111]:226

Outside of Southeast Asia, megabats have relatively low species richness in Asia. The Egyptian fruit bat is the only megabat whose range is mostly in the Palearctic realm;[112] it and the straw-colored fruit bat are the only species found in the Middle East.[112][113] The northernmost extent of the Egyptian fruit bat's range is the northeastern Mediterranean.[112] In East Asia, megabats are found only in China and Japan. In China, only six species of megabat are considered resident, while another seven are present marginally (at the edge of their ranges), questionably (due to possible misidentification), or as accidental migrants.[114] Four megabat species, all Pteropus, are found on Japan, but none on its five main islands.[115][116][117][118] In South Asia, megabat species richness ranges from two species in the Maldives to thirteen species in India.[119] Megabat species richness in Southeast Asia is as few as five species in the small country of Singapore and seventy-six species in Indonesia.[119] Of the ninety-eight species of megabat found in Asia, forest is a habitat for ninety-five of them. Other habitat types include human-modified land (66 species), caves (23 species), savanna (7 species), shrubland (4 species), rocky areas (3 species), grassland (2 species), and desert (1 species).[119]

In Australia, five genera and eight species of megabat are present. These genera are Pteropus, Syconycteris, Dobsonia, Nyctimene, and Macroglossus.[41]:3 Pteropus species of Australia are found in a variety of habitats, including mangrove-dominated forests, rainforests, and the wet sclerophyll forests of the Australian bush.[41]:7 Australian Pteropus are often found in association with humans, as they situate their large colonies in urban areas, particularly in May and June when the greatest proportions of Pteropus species populations are found in these urban colonies.[120]

In Oceania, the countries of Palau and Tonga have the fewest megabat species, with one each. Papua New Guinea has the greatest number of species with thirty-six.[121] Of the sixty-five species of Oceania, forest is a habitat for fifty-eight. Other habitat types include human-modified land (42 species), caves (9 species), savanna (5 species), shrubland (3 species), and rocky areas (3 species).[121] An estimated nineteen percent of all megabat species are endemic to a single island; of all bat families, only Myzopodidae—containing two species, both single-island endemics—has a higher rate of single-island endemism.[122]

Relationship to humans

Food

Megabats are killed and eaten as bushmeat throughout their range. Bats are consumed extensively throughout Asia, as well as in islands of the West Indian Ocean and the Pacific, where Pteropus species are heavily hunted. In continental Africa where no Pteropus species live, the straw-coloured fruit bat, the region's largest megabat, is a preferred hunting target.[123]

In Guam, consumption of the Mariana fruit bat exposes locals to the neurotoxin beta-Methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) which may later lead to neurodegenerative diseases. BMAA may become particularly biomagnified in humans who consume flying foxes; flying foxes are exposed to BMAA by eating cycad fruits.[124][125][126]

As disease reservoirs

Megabats are the reservoirs of several viruses that can affect humans and cause disease. They can carry filoviruses, including the Ebola virus (EBOV) and Marburgvirus.[127] The presence of Marburgvirus, which causes Marburg virus disease, has been confirmed in one species, the Egyptian fruit bat. The disease is rare, but the fatality rate of an outbreak can reach up to 88%.[127][128] The virus was first recognized after simultaneous outbreaks in the German cities of Marburg and Frankfurt as well as Belgrade, Serbia in 1967[128] where 31 people became ill and seven died.[129] The outbreak was traced to laboratory work with vervet monkeys from Uganda.[128] The virus can pass from a bat host to a human (who has usually spent a prolonged period in a mine or cave where Egyptian fruit bats live); from there, it can spread person-to-person through contact with infected bodily fluids, including blood and semen.[128] The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists a total of 601 confirmed cases of Marburg virus disease from 1967 to 2014, of which 373 people died (62% overall mortality).[129]

Species that have tested positive for the presence of EBOV include Franquet's epauletted fruit bat (Epomops franqueti), the hammer-headed fruit bat, and the little collared fruit bat. Additionally, antibodies against EBOV have been found in the straw-coloured fruit bat, Gambian epauletted fruit bat (Epomophorus gambianus), Peters's dwarf epauletted fruit bat (Micropteropus pusillus), Veldkamp's dwarf epauletted fruit bat (Nanonycteris veldkampii), Leschenault's rousette, and the Egyptian fruit bat.[127] Much of how humans contract the Ebola virus is unknown. Scientists hypothesize that humans initially become infected through contact with an infected animal such as a megabat or non-human primate.[130] Megabats are presumed to be a natural reservoir of the Ebola virus, but this has not been firmly established.[131] Microbats are also being investigated as the reservoir of the virus, with the greater long-fingered bat (Miniopterus inflatus) once found to harbor a fifth of the virus's genome (though not testing positive for the actual virus) in 2019.[132] Due to the likely association between Ebola infection and "hunting, butchering and processing meat from infected animals", several West African countries banned bushmeat (including megabats) or issued warnings about it during the 2013–2016 epidemic; many bans have since been lifted.[133]

Other megabats implicated as disease reservoirs are primarily Pteropus species. Notably, flying foxes can transmit Australian bat lyssavirus, which, along with the rabies virus, causes rabies. Australian bat lyssavirus was first identified in 1996; it is very rarely transmitted to humans. Transmission occurs from the bite or scratch of an infected animal but can also occur from getting the infected animal's saliva in a mucous membrane or an open wound. Exposure to flying fox blood, urine, or feces cannot cause infections of Australian bat lyssavirus. Since 1994, there have been three records of people becoming infected with it in Queensland—each case was fatal.[134]

Flying foxes are also reservoirs of henipaviruses such as Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Hendra virus was first identified in 1994; it rarely occurs in humans. From 1994 to 2013, there have been seven reported cases of Hendra virus affecting people, four of which were fatal. The hypothesized primary route of human infection is via contact with horses that have come into contact with flying fox urine.[135] There are no documented instances of direct transmission between flying foxes and humans.[136] As of 2012, there is a vaccine available for horses to decrease the likelihood of infection and transmission.[137]

Nipah virus was first identified in 1998 in Malaysia. Since 1998, there have been several Nipah outbreaks in Malaysia, Singapore, India, and Bangladesh, resulting in over 100 casualties. A 2018 outbreak in Kerala, India resulted in 19 humans becoming infected—17 died.[138] The overall fatality rate is 40–75%. Humans can contract Nipah virus from direct contact with flying foxes or their fluids, through exposure to an intermediate host such as domestic pigs, or from contact with an infected person.[139] A 2014 study of the Indian flying fox and Nipah virus found that while Nipah virus outbreaks are more likely in areas preferred by flying foxes, "the presence of bats in and of itself is not considered a risk factor for Nipah virus infection." Rather, the consumption of date palm sap is a significant route of transmission. The practice of date palm sap collection involves placing collecting pots at date palm trees. Indian flying foxes have been observed licking the sap as it flows into the pots, as well as defecating and urinating in proximity to the pots. In this way, humans who drink the palm sap can be exposed to the bats' viruses. The use of bamboo skirts on collecting pots lowers the risk of contamination from bat fluids.[140]

Flying foxes can transmit several non-lethal diseases as well, such as Menangle virus[141] and Nelson Bay virus.[142] These viruses rarely affect humans, and few cases have been reported.[141][142] While other bat species have been suspected or implicated as the reservoir of diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), megabats are not suspected as the host for the causative virus.[143]

In culture

Megabats, particularly flying foxes, are featured in indigenous cultures and traditions. Folk stories from Australia and Papua New Guinea feature them.[144][145] They were also included in Indigenous Australian cave art, as evinced by several surviving examples.[146]

Indigenous societies in Oceania used parts of flying foxes for functional and ceremonial weapons. In the Solomon Islands, people created barbs out of their bones for use in spears.[147] In New Caledonia, ceremonial axes made of jade were decorated with braids of flying fox fur.[148] Flying fox wings were depicted on the war shields of the Asmat people of Indonesia; they believed that the wings offered protection to their warriors.[149]

There are modern and historical references to flying fox byproducts used as currency. In New Caledonia, braided flying fox fur was once used as currency.[147] On the island of Makira, which is part of the Solomon Islands, indigenous peoples still hunt flying foxes for their teeth as well as for bushmeat. The canine teeth are strung together on necklaces that are used as currency.[150] Teeth of the insular flying fox (Pteropus tonganus) are particularly prized, as they are usually large enough to drill holes in. The Makira flying fox (Pteropus cognatus) is also hunted, despite its smaller teeth. Deterring people from using flying fox teeth as currency may be detrimental to the species, with Lavery and Fasi noting, "Species that provide an important cultural resource can be highly treasured." Emphasizing sustainable hunting of flying foxes to preserve cultural currency may be more effective than encouraging the abandonment of cultural currency. Even if flying foxes were no longer hunted for their teeth, they would still be killed for bushmeat; therefore, retaining their cultural value may encourage sustainable hunting practices.[151] Lavery stated, "It's a positive, not a negative, that their teeth are so culturally valuable. The practice of hunting bats shouldn't necessarily be stopped, it needs to be managed sustainably."[150]

Conservation

Status

As of 2014, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) evaluated a quarter of all megabat species as threatened, which includes species listed as critically endangered, endangered, and vulnerable. Megabats are substantially threatened by humans, as they are hunted for food and medicinal uses. Additionally, they are culled for actual or perceived damage to agriculture, especially to fruit production.[152] As of 2019, the IUCN had evaluations for 187 megabat species. The status breakdown is as follows:[153]

- Extinct: 4 species (2.1%)

- Critically endangered: 8 species (4.3%)

- Endangered: 16 species (8.6%)

- Vulnerable: 37 species (19.8%)

- Near-threatened: 13 species (7.0%)

- Least-concern: 89 species (47.6%)

- Data deficient: 20 species (10.7%)

Factors causing decline

Anthropogenic sources

Megabats are threatened by habitat destruction by humans. Deforestation of their habitats has resulted in the loss of critical roosting habitat. Deforestation also results in the loss of food resource, as native fruit-bearing trees are felled. Habitat loss and resulting urbanization leads to construction of new roadways, making megabat colonies easier to access for overharvesting. Additionally, habitat loss via deforestation compounds natural threats, as fragmented forests are more susceptible to damage from typhoon-force winds.[70]:7 Cave-roosting megabats are threatened by human disturbance at their roost sites. Guano mining is a livelihood in some countries within their range, bringing people to caves. Caves are also disturbed by mineral mining and cave tourism.[70]:8

Megabats are also killed by humans, intentionally and unintentionally. Half of all megabat species are hunted for food, in comparison to only eight percent of insectivorous species,[154] while human persecution stemming from perceived damage to crops is also a large source of mortality. Some megabats have been documented to have a preference for native fruit trees over fruit crops, but deforestation can reduce their food supply, causing them to rely on fruit crops.[70]:8 They are shot, beaten to death, or poisoned to reduce their populations. Mortality also occurs via accidental entanglement in netting used to prevent the bats from eating fruit.[155] Culling campaigns can dramatically reduce megabat populations. In Mauritius, over 40,000 Mauritian flying foxes were culled between 2014 and 2016, reducing the species' population by an estimated 45%.[156] Megabats are also killed by electrocution. In one Australian orchard, it is estimated that over 21,000 bats were electrocuted to death in an eight-week period.[157] Farmers construct electrified grids over their fruit trees to kill megabats before they can consume their crop. The grids are questionably effective at preventing crop loss, with one farmer who operated such a grid estimating they still lost 100–120 tonnes (220,000–260,000 lb) of fruit to flying foxes in a year.[158] Some electrocution deaths are also accidental, such as when bats fly into overhead power lines.[159]

Climate change causes flying fox mortality and is a source of concern for species persistence. Extreme heat waves in Australia have been responsible for the deaths of more than 30,000 flying foxes from 1994 to 2008. Females and young bats are most susceptible to extreme heat, which affects a population's ability to recover.[160] Megabats are threatened by sea level rise associated with climate change, as several species are endemic to low-lying atolls.[161]

Natural sources

Because many species are endemic to a single island, they are vulnerable to random events such as typhoons. A 1979 typhoon halved the remaining population of the Rodrigues flying fox (Pteropus rodricensis). Typhoons result in indirect mortality as well: because typhoons defoliate the trees, they make megabats more visible and thus more easily hunted by humans. Food resources for the bats become scarce after major storms, and megabats resort to riskier foraging strategies such as consuming fallen fruit off the ground. There, they are more vulnerable to depredation by domestic cats, dogs, and pigs.[93] As many megabat species are located in the tectonically active Ring of Fire, they are also threatened by volcanic eruptions. Flying foxes, including the endangered Mariana fruit bat,[118][162] have been nearly exterminated from the island of Anatahan following a series of eruptions beginning in 2003.[163]

References

- McKenna, M. C.; Bell, S. K. (1997). Classification of mammals: above the species level. Columbia University Press. p. 296. ISBN 9780231528535.

- Almeida, F.; Giannini, N. P.; Simmons, N. B. (2016). "The Evolutionary History of the African Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Acta Chiropterologica. 18: 73–90. doi:10.3161/15081109ACC2016.18.1.003.

- Gray, J. E. (1821). "On the natural arrangement of vertebrose animals". London Medical Repository (25): 299.

- Miller, Jr., Gerrit S. (1907). "The Families and Genera of Bats". United States National Museum Bulletin. 57: 63.

- Hutcheon, J. M.; Kirsch, J. A. (2006). "A moveable face: deconstructing the Microchiroptera and a new classification of extant bats". Acta Chiropterologica. 8 (1): 1–10. doi:10.3161/1733-5329(2006)8[1:AMFDTM]2.0.CO;2.

- "Definition of PTEROPUS". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Jackson, S.; Jackson, S. M.; Groves, C. (2015). Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 9781486300136.

- Dobson, G. E. (1875). "Conspectus of the suborders, families, and genera of Chiroptera arranged according to their natural affinities". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 4. 16 (95).

- Springer, M. S.; Teeling, E. C.; Madsen, O.; Stanhope, M. J.; De Jong, W. W. (2001). "Integrated fossil and molecular data reconstruct bat echolocation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (11): 6241–6246. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.6241S. doi:10.1073/pnas.111551998. PMC 33452. PMID 11353869.

- Lei, M.; Dong, D. (2016). "Phylogenomic analyses of bat subordinal relationships based on transcriptome data". Scientific Reports. 6 (27726): 27726. Bibcode:2016NatSR...627726L. doi:10.1038/srep27726. PMC 4904216. PMID 27291671.

- Tsagkogeorga, G.; Parker, J.; Stupka, E.; Cotton, J. A.; Rossiter, S. J. (2013). "Phylogenomic Analyses Elucidate the Evolutionary Relationships of Bats". Current Biology. 23 (22): 2262–2267. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.014. PMID 24184098.

- Szcześniak, M.; Yoneda, M.; Sato, H.; Makałowska, I.; Kyuwa, S.; Sugano, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Makałowski, W.; Kai, C. (2014). "Characterization of the mitochondrial genome of Rousettus leschenaulti". Mitochondrial DNA. 25 (6): 443–444. doi:10.3109/19401736.2013.809451. PMID 23815317.

- Teeling, E. C.; Springer, M. S.; Madsen, O.; Bates, P.; O'Brien, S. J.; Murphy, W. J. (2005). "A Molecular Phylogeny for Bats Illuminates Biogeography and the Fossil Record". Science. 307 (5709): 580–584. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..580T. doi:10.1126/science.1105113. PMID 15681385.

- Ungar, P. (2010). Mammal Teeth: Origin, Evolution, and Diversity. JHU Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780801899515.

- Giannini, N. P.; Simmons, N. B. (2003). "A phylogeny of megachiropteran bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) based on direct optimization analysis of one nuclear and four mitochondrial genes". Cladistics. 19 (6): 496–511. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00385.x.

- Colgan, D. J.; Flannery, T. F. (1995). "A Phylogeny of Indo-West Pacific Megachiroptera Based on Ribosomal DNA". Systematic Biology. 44 (2): 209–220. doi:10.1093/sysbio/44.2.209.

- Bergmans, W. (1997). "Taxonomy and biogeography of African fruit bats (Mammalia, Megachiroptera). 5. The genera Lissonycteris Andersen, 1912, Myonycteris Matschie, 1899 and Megaloglossus Pagenstecher, 1885; general remarks and conclusions; annex: key to all species". Beaufortia. 47 (2): 69.

- Almeida, F. C.; Giannini, N. P.; Desalle, R.; Simmons, N. B. (2011). "Evolutionary relationships of the old world fruit bats (Chiroptera, Pteropodidae): Another star phylogeny?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11: 281. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-281. PMC 3199269. PMID 21961908.

- Butler, P. M. (1984). "Macroscelidea, Insectivora and Chiroptera from the Miocene of east Africa". Palaeovertebrata. 14 (3): 175.

- Gunnell, G. F.; Boyer, D. M.; Friscia, A. R.; Heritage, S.; Manthi, F. K.; Miller, E. R.; Sallam, H. M.; Simmons, N. B.; Stevens, N. J.; Seiffert, E. R. (2018). "Fossil lemurs from Egypt and Kenya suggest an African origin for Madagascar's aye-aye". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3193. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3193G. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05648-w. PMC 6104046. PMID 30131571.

- Burgin, Connor J; Colella, Jocelyn P; Kahn, Philip L; Upham, Nathan S (2018). "How many species of mammals are there?". Journal of Mammalogy. 99 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyx147. ISSN 0022-2372.

- "Taxonomy=Pteropus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- Eiting, T. P.; Gunnell, G. F. (2009). "Global Completeness of the Bat Fossil Record". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 16 (3): 157. doi:10.1007/s10914-009-9118-x.

- Teeling, E. C.; Springer, M. S.; Madsen, O.; Bates, P.; O'Brien, S. J.; Murphy, W. J. (2005). "A Molecular Phylogeny for Bats Illuminates Biogeography and the Fossil Record" (PDF). Science. 307 (5709): 580–584. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..580T. doi:10.1126/science.1105113. PMID 15681385.

- Almeida, F. C.; Giannini, N. P.; Desalle, Rob; Simmons, N. B. (2009). "The phylogenetic relationships of cynopterine fruit bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae: Cynopterinae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 53 (3): 772–783. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.07.035. hdl:11336/74530. PMID 19660560.

- O'Brien, J.; Mariani, C.; Olson, L.; Russell, A. L.; Say, L.; Yoder, A. D.; Hayden, T. J. (2009). "Multiple colonisations of the western Indian Ocean by Pteropus fruit bats (Megachiroptera: Pteropodidae): The furthest islands were colonised first". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 51 (2): 294–303. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.02.010. PMID 19249376.

- Teeling EC, Jones G, Rossiter SJ (2016). "Phylogeny, Genes, and Hearing: Implications for the Evolution of Echolocation in Bats". In Fenton MB, Grinnell AD, Popper AN, Fay RN (eds.). Bat Bioacoustics. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. 54. New York: Springer. pp. 25–54. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3527-7_2. ISBN 9781493935277.

- Wang, Zhe; Zhu, Tengteng; Xue, Huiling; Fang, Na; Zhang, Junpeng; Zhang, Libiao; Pang, Jian; Teeling, Emma C.; Zhang, Shuyi (2017). "Prenatal development supports a single origin of laryngeal echolocation in bats". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (2): 21. doi:10.1038/s41559-016-0021. PMID 28812602.

- Holland, R. A.; Waters, D. A.; Rayner, J. M. (December 2004). "Echolocation signal structure in the Megachiropteran bat Rousettus aegyptiacus Geoffroy 1810". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (Pt 25): 4361–4369. doi:10.1242/jeb.01288. PMID 15557022.

- Boonman, A.; Bumrungsri, S.; Yovel, Y. (December 2014). "Nonecholocating fruit bats produce biosonar clicks with their wings". Current Biology. 24 (24): 2962–2967. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.077. PMID 25484290.

- Speakman, J. R.; Racey, P. A. (April 1991). "No cost of echolocation for bats in flight". Nature. 350 (6317): 421–423. Bibcode:1991Natur.350..421S. doi:10.1038/350421a0. PMID 2011191.

- Lancaster, W. C.; Henson, O. W.; Keating, A. W. (January 1995). "Respiratory muscle activity in relation to vocalization in flying bats" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 198 (Pt 1): 175–191. PMID 7891034.

- Altringham JD (2011). "Echolocation and other senses". Bats: From Evolution to Conservation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199207114.

- Hutcheon JM, Garland TJ (1995). "Are megabats big?". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 11 (3/4): 257–277. doi:10.1023/B:JOMM.0000047340.25620.89.

- Gunnell, Gregg F.; Manthi, Fredrick K. (April 2018). "Pliocene bats (Chiroptera) from Kanapoi, Turkana Basin, Kenya". Journal of Human Evolution. 140: 4. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.01.001. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 29628118.

- Flannery, T. (1995). Mammals of the South-West Pacific & Moluccan Islands. Cornell University Press. p. 271. ISBN 0801431506.

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Nowak, R. M.; Walker, E. P.; Kunz, T. H.; Pierson, E. D. (1994). Walker's bats of the world. JHU Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780801849862.

- Hutcheon, J. M.; Garland Jr, T. (2004). "Are Megabats Big?". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 11 (3/4): 257–277. doi:10.1023/B:JOMM.0000047340.25620.89.

- Geist, V.; Kleiman, D. G.; McDade, M. C. (2004). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia Mammals II. Volume 13 (2nd ed.). Gale. p. 309.

- Nelson, J. E. Fauna of Australia (PDF) (Report). 1B. Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy.

- Santana, S. E.; Dial, T. O.; Eiting, T. P.; Alfaro, M. E. (2011). "Roosting Ecology and the Evolution of Pelage Markings in Bats". PLOS One. 6 (10): e25845. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625845S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025845. PMC 3185059. PMID 21991371.

- Hall, L. S.; Richards, G. (2000). Flying Foxes: Fruit and Blossom Bats of Australia. UNSW Press. ISBN 9780868405612.

- Ingleby, S.; Colgan, D. (2003). "Electrophoretic studies of the systematic and biogeographic relationships of the Fijian bat genera Pteropus, Pteralopex, Chaerephon and Notopteris". Australian Mammalogy. 25: 13. doi:10.1071/AM03013.

- Vaughan, T. A.; Ryan, J. M.; Czaplewski, N. J. Mammalogy (6 ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9781284032185.

- Simmons, Nancy B.; Conway, Tenley M. (2001). "Phylogenetic Relationships of Mormoopid Bats (Chiroptera: Mormoopidae) Based on Morphological Data". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 258: 17. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2001)258<0001:PROMBC>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/1608. ISSN 0003-0090.

- Lindenau, Christa (2011). "Middle Pleistocene bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the Yarimburgaz Cave in Turkish Thrace (Turkey)". E&G – Quaternary Science Journal. 55: 127. doi:10.23689/fidgeo-999.

- Tate, G. H. H. (1942). "Results of the Archbold Expeditions No. 48: Pteropodidae (Chiroptera) of the Archbold Collections". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 80: 332–335.

- Giannini, N. P.; Simmons, N. B. (2007). "Element homology and the evolution of dental formulae in megachiropteran bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3559: 1–27. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2007)3559[1:EHATEO]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5849.

- Juste, J.; Ibáñez, C. (1993). "An asymmetric dental formula in a mammal, the Sao Tomé Island fruit bat Myonycteris brachycephala (Mammalia: Megachiroptera)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 71 (1): 221–224. doi:10.1139/z93-030. hdl:10261/48798.

- Vaughan, T. (1970). "Chapter 3: The Skeletal System". In Wimsatt, W. (ed.). Biology of Bats. Academic Press. pp. 103–136. ISBN 9780323151191.

- Luo, Z. X.; Kielan-Jaworowska, Z.; Cifelli, R. L. (2004). "Evolution of dental replacement in mammals" (PDF). Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. 2004 (36): 159–176. doi:10.2992/0145-9058(2004)36[159:EODRIM]2.0.CO;2.

- Nowak, R. M.; Pillsbury Walker, E. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Volume 1. JHU Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780801857898.

- Bennett, M. B. (1993). "Structural modifications involved in the fore- and hind limb grip of some flying foxes (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Journal of Zoology. 229 (2): 237–248. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1993.tb02633.x.

- Schutt, W. A.; Simmons, N. B. (1998). "Morphology and Homology of the Chiropteran Calca, with Comments on the Phylogenetic Relationships of Archaeopteropus". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 5: 2. doi:10.1023/A:1020566902992.

- Maina, J. N.; King, A. S. (1984). "Correlations between structure and function in the design of the bat lung: a morphometric study" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 11: 44.

- Carpenter, R. E. (1986). "Flight Physiology of Intermediate-Sized Fruit Bats (Pteropodidae)" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 120: 84–93.

- Richards, G. C. (1983). "Fruit-bats and their relatives". In Strahan, R. (ed.). Complete book of Australian mammals. The national photographic index of Australian wildlife (1 ed.). London: Angus & Robertson. pp. 271–273. ISBN 978-0207144547.

- Schmidt-Rhaesa, A., ed. (2017). Comparative Anatomy of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Eutheria II. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 328–330. ISBN 9783110560671.

- Smith, J. D. L.; Gregory, T. R. (2009). "The genome sizes of megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) are remarkably constrained". Biology Letters. 5 (3): 347–351. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0016. PMC 2679926. PMID 19324635.

- Müller, B.; Goodman, S. M.; Peichl, Leo (2007). "Cone Photoreceptor Diversity in the Retinas of Fruit Bats (Megachiroptera)". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 70 (2): 90–104. doi:10.1159/000102971. PMID 17522478.

- Graydon, M.; Giorgi, P.; Pettigrew, J. (1987). "Vision in Flying-Foxes (Chiroptera:Pteropodidae)". Journal of the Australian Mammal Society. 10 (2): 101–105.

- Thiagavel, J.; Cechetto, C.; Santana, S. E.; Jakobsen, L.; Warrant, E. J.; Ratcliffe, J. M. (2018). "Auditory opportunity and visual constraint enabled the evolution of echolocation in bats". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 98. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9...98T. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02532-x. PMC 5758785. PMID 29311648.

- Giannini, N. P.; Almeida, F. C.; Simmons, N. B.; Helgen, K. M. (2008). "The systematic position of Pteropus leucopterus and its bearing on the monophyly and relationships of Pteropus (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Acta Chiropterologica. 10: 11–20. doi:10.3161/150811008X331054. hdl:11336/82001.

- Jones, G.; Teeling, E. C.; Rossiter, S. J. (2013). "From the ultrasonic to the infrared: Molecular evolution and the sensory biology of bats". Frontiers in Physiology. 4: 117. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00117. PMC 3667242. PMID 23755015.

- Schwab, I. R. (2005). "A choroidal sleight of hand". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 89 (11): 1398. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.077966. PMC 1772916. PMID 16267906.

- Wood, W. F.; Walsh, A.; Seyjagat, J.; Weldon, P. J. (2005). "Volatile Compounds in Shoulder Gland Secretions of Male Flying Foxes, Genus Pteropus (Pteropodidae, Chiroptera)". Z Naturforsch C. 60 (9–10): 779–784. doi:10.1515/znc-2005-9-1019. PMID 16320623.

- Wagner, J. (2008). "Glandular secretions of male Pteropus (Flying foxes): preliminary chemical comparisons among species". Independent Study Project (Isp) Collection.

- Li, D.; Zhang, J. (2014). "Diet Shapes the Evolution of the Vertebrate Bitter Taste Receptor Gene Repertoire". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (2): 303–309. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst219. PMC 3907052. PMID 24202612.

- Mickleburgh, S. P.; Hutson, A. M.; Racey, P. A. (1992). Old World fruit bats: An action plan for their conservation (PDF) (Report). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Hengjan, Yupadee; Iida, Keisuke; Doysabas, Karla Cristine C.; Phichitrasilp, Thanmaporn; Ohmori, Yasushige; Hondo, Eiichi (2017). "Diurnal behavior and activity budget of the golden-crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) in the Subic bay forest reserve area, the Philippines". Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 79 (10): 1667–1674. doi:10.1292/jvms.17-0329. PMC 5658557. PMID 28804092.

- Heideman, P. D. (1988). "The timing of reproduction in the fruit bat Haplonycteris fischeri (Pteropodidae): Geographic variation and delayed development". Journal of Zoology. 215 (4): 577–595. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1988.tb02396.x. hdl:2027.42/72984.

- Nowak, R. M.; Pillsbury Walker, E. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Volume 1. JHU Press. p. 287. ISBN 9780801857898.

- Fox, Samantha; Spencer, Hugh; O'Brien, Gemma M. (2008). "Analysis of twinning in flying-foxes (Megachiroptera) reveals superfoetation and multiple-paternity". Acta Chiropterologica. 10 (2): 271–278. doi:10.3161/150811008X414845.

- Sreenivasan, M. A.; Bhat, H. R.; Geevarghese, G. (30 March 1974). "Observations on the Reproductive Cycle of Cynopterus sphinx sphinx Vahl, 1797 (Chiroptera: Pteropidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 55 (1): 200–202. doi:10.2307/1379269. JSTOR 1379269.

- Douglass Hayssen, V.; Van Tienhoven, A.; Van Tienhoven, A. (1993). Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: A Compendium of Species-specific Data. Cornell University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780801417535.

- Altringham, John D.; McOwat, Tom; Hammond, Lucy (2011). Bats: from evolution to conservation (2nd ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-19-920711-4.

- Kunz, T. H.; Kurta, A. (1987). "Size of bats at birth and maternal investment during pregnancy" (PDF). Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. 57.

- Safi, K. (2008). "Social Bats: The Males' Perspective". Journal of Mammalogy. 89 (6): 1342–1350. doi:10.1644/08-MAMM-S-058.1.

- Crichton, E. G.; Krutzsch, P. H., eds. (2000). Reproductive Biology of Bats. Academic Press. p. 433. ISBN 9780080540535.

- Racey, D. N.; Peaker, M.; Racey, P. A. (2009). "Galactorrhoea is not lactation". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (7): 354–355. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.008. PMID 19427057.

- Kunz, T. H; Hosken, David J (2009). "Male lactation: Why, why not and is it care?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (2): 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.09.009. PMID 19100649.

- Schoeman, M. C.; Goodman, S. M. (2012). "Vocalizations in the Malagasy Cave-Dwelling Fruit Bat, Eidolon dupreanum: Possible Evidence of Incipient Echolocation?". Acta Chiropterologica. 14 (2): 409. doi:10.3161/150811012X661729.

- "Hammer-headed Fruit Bat". BATS Magazine. Vol. 34 no. 1. 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Loveless, A. M.; McBee, K. (2017). "Nyctimene robinsoni (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Mammalian Species. 49 (949): 68–75. doi:10.1093/mspecies/sex007.

- Prat, Yosef; Taub, Mor; Yovel, Yossi (2015). "Vocal learning in a social mammal: Demonstrated by isolation and playback experiments in bats". Science Advances. 1 (2): e1500019. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500019. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4643821. PMID 26601149.

- Vernes, S. C. (2017). "What bats have to say about speech and language". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 24 (1): 111–117. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1060-3. PMC 5325843. PMID 27368623.

- Prat, Yosef; Azoulay, Lindsay; Dor, Roi; Yovel, Yossi (2017). "Crowd vocal learning induces vocal dialects in bats: Playback of conspecifics shapes fundamental frequency usage by pups". PLOS Biology. 15 (10): e2002556. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2002556. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5663327. PMID 29088225.

- Zimmer, K. (1 January 2018). "What Bat Quarrels Tell Us About Vocal Learning". The Scientist. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Harten, L.; Prat, Y.; Ben Cohen, S.; Dor, R.; Yovel, Y. (2019). "Food for Sex in Bats Revealed as Producer Males Reproduce with Scrounging Females". Current Biology. 29 (11): 1895–1900.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.066. PMID 31130455.

- Sugita, N. (2016). "Homosexual Fellatio: Erect Penis Licking between Male Bonin Flying Foxes Pteropus pselaphon". PLOS One. 11 (11): e0166024. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1166024S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166024. PMC 5100941. PMID 27824953.

- Tan, M.; Jones, G.; Zhu, G.; Ye, J.; Hong, T.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L. (2009). "Fellatio by Fruit Bats Prolongs Copulation Time". PLOS One. 4 (10): e7595. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7595T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007595. PMC 2762080. PMID 19862320.

- Pierson, E. D.; Rainey, W. E. (1992). "The biology of flying foxes of the genus Pteropus: a review". Biological Report. 90 (23).

- Dumont, E. R.; O'Neal, R. (2004). "Food Hardness and Feeding Behavior in Old World Fruit Bats (Pteropodidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 85: 8–14. doi:10.1644/BOS-107.

- Yin, Q.; Zhu, L.; Liu, D.; Irwin, D. M.; Zhang, S.; Pan, Y. (2016). "Molecular Evolution of the Nuclear Factor (Erythroid-Derived 2)-Like 2 Gene Nrf2 in Old World Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". PLOS One. 11 (1): e0146274. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1146274Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146274. PMC 4703304. PMID 26735303.

- Courts, S. E. (1998). "Dietary strategies of Old World Fruit Bats (Megachiroptera, Pteropodidae): How do they obtain sufficient protein?". Mammal Review. 28 (4): 185–194. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.1998.00033.x.

- Norberg, U.M. & Rayner, J.M.V. (1987). "Ecological morphology and flight in bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera): wing adaptations, flight performance, foraging strategy and echolocation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 316 (1179): 382–383. Bibcode:1987RSPTB.316..335N. doi:10.1098/rstb.1987.0030.

- Hodgkison, R.; Balding, S. T.; Zubaid, A.; Kunz, T. H. (2003). "Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) as Seed Dispersers and Pollinators in a Lowland Malaysian Rain Forest1". Biotropica. 35 (4): 491–502. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2003.tb00606.x.

- Shilton, L. A.; Altringham, J. D.; Compton, S. G.; Whittaker, R. J. (1999). "Old World fruit bats can be long-distance seed dispersers through extended retention of viable seeds in the gut". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1416): 219–223. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0625. PMC 1689670.

- Oleksy, R.; Racey, P. A.; Jones, G. (2015). "High-resolution GPS tracking reveals habitat selection and the potential for long-distance seed dispersal by Madagascan flying foxes Pteropus rufus". Global Ecology and Conservation. 3: 690. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2015.02.012.

- Corlett, R. T. (2017). "Frugivory and seed dispersal by vertebrates in tropical and subtropical Asia: An update". Global Ecology and Conservation. 11: 13. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2017.04.007.

- Reeder, D. M.; Kunz, T. H.; Widmaier, E. P. (2004). "Baseline and stress-induced glucocorticoids during reproduction in the variable flying fox, Pteropus hypomelanus (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 301A (8): 682–690. doi:10.1002/jez.a.58. PMID 15286948.

- Buden, D.; Helgen, K. M.; Wiles, G. (2013). "Taxonomy, distribution, and natural history of flying foxes (Chiroptera, Pteropodidae) in the Mortlock Islands and Chuuk State, Caroline Islands". ZooKeys (345): 127. doi:10.3897/zookeys.345.5840. PMC 3817444. PMID 24194666.

- Esselstyn, J. A.; Amar, A.; Janeke, D. (2006). "Impact of Posttyphoon Hunting on Mariana Fruit Bats (Pteropus mariannus)". Pacific Science. 60 (4): 531–532. doi:10.1353/psc.2006.0027.

- Adame, Maria Fernanda; Jardine, T. D.; Fry, B.; Valdez, D.; Lindner, G.; Nadji, J.; Bunn, S. E. (2018). "Estuarine crocodiles in a tropical coastal floodplain obtain nutrition from terrestrial prey". PLOS One. 13 (6): e0197159. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1397159A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197159. PMC 5991389. PMID 29874276.

- Flying Foxes Vs Freshwater Crocodile (video). BBC Earth. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Ramasindrazana, B.; Goodman, S. M.; Gomard, Y.; Dick, C. W.; Tortosa, P. (2017). "Hidden diversity of Nycteribiidae (Diptera) bat flies from the Malagasy region and insights on host-parasite interactions". Parasites & Vectors. 10 (1): 630. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2582-x. PMC 5747079. PMID 29284533.

- Ramanantsalama, R. V.; Andrianarimisa, A.; Raselimanana, A. P.; Goodman, S. M. (2018). "Rates of hematophagous ectoparasite consumption during grooming by an endemic Madagascar fruit bat". Parasites & Vectors. 11 (1): 330. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2918-1. PMC 5984742. PMID 29859123.

- Desch, C. E. (1981). "A new species of demodicid mite (Acari: Prostigmata) from Western Australia parasitic on Macroglossus minimus (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)" (PDF). Records of the Western Australian Museum. 9 (1): 41–47.

- Landau, I.; Chavatte, J. M.; Karadjian, G.; Chabaud, A.; Beveridge, I. (2012). "The haemosporidian parasites of bats with description of Sprattiella alectogen. Nov., sp. Nov". Parasite. 19 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1051/parasite/2012192137. PMC 3671437. PMID 22550624.

- Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (2013). Mammals of Africa. 4. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408189962.

- Benda, Petr; Vallo, Peter; Hulva, Pavel; Horáček, Ivan (2012). "The Egyptian fruit bat Rousettus aegyptiacus (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) in the Palaearctic: Geographical variation and taxonomic status". Biologia. 67 (6). doi:10.2478/s11756-012-0105-y.

- Mickleburgh, S.; Hutson, A.M.; Bergmans, W.; Fahr, J.; Racey, P.A. (2008). "Eidolon helvum". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T7084A12824968. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T7084A12824968.en.

- Zhang, Jin-Shuo; Jones, Gareth; Zhang, Li-Biao; Zhu, Guang-Jian; Zhang, Shu-Yi (2010). "Recent Surveys of Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from China II. Pteropodidae". Acta Chiropterologica. 12: 103–116. doi:10.3161/150811010X504626.

- Vincenot, C. (2017). "Pteropus dasymallus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2017: e.T18722A22080614. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T18722A22080614.en.

- Maeda, K. (2008). "Pteropus loochoensis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T18773A8614831. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T18773A8614831.en.

- Vincenot, C. (2017). "Pteropus pselaphon". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2017: e.T18752A22085351. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T18752A22085351.en.

- Allison, A.; Bonaccorso, F.; Helgen, K. & James, R. (2008). "Pteropus mariannus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2008: e.T18737A8516291. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T18737A8516291.en.