Bougainville monkey-faced bat

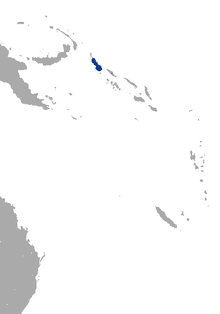

The Bougainville monkey-faced bat (Pteralopex anceps) is a megabat endemic to Bougainville Island of Papua New Guinea and Choiseul Island of the Solomon Islands in Melanesia.[2] It inhabits mature forests in upland areas, within the Autonomous Region of Bougainville and Bougouriba Province.

| Bougainville monkey-faced bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Pteropodidae |

| Genus: | Pteralopex |

| Species: | P. anceps |

| Binomial name | |

| Pteralopex anceps K. Andersen, 1909 | |

| |

| Bougainville Monkey-faced Bat range | |

Discovery and taxonomy

It was first collected by English naturalist Albert Stewart Meek in April 1904 from Bougainville Island. That specimen was later used by Danish zoologist Knud Andersen in 1909 to describe a new species.[3] The species name anceps comes from Latin, meaning "double-headed" or "having two heads." This could possibly be a reference to it being the second described member of Pteralopex, or that it had characters similar to both Pteralopex and Pteropus, especially the Bonin flying fox.[4] In 1954, it was listed as a subspecies of the Guadalcanal monkey-faced bat.[5] In 1978, it was once again listed a separate species.[6] Some have considered it synonymous with the greater monkey-faced bat,[7] which is found in the same range, while others maintain them as separate species.[3]

Description

It is the largest member of its genus, Pteralopex.[2] Their forearms are 141–160 millimetres (5.6–6.3 in) long.[3] They can be identified by their short ears, mostly obscured by their fur. They have black fur on their heads and backs. Their chests have a white or yellow patch.[2] The fur is long, with individual hairs approximately 20 mm (0.79 in) Unlike the Guadalcanal monkey-faced bat, the tibia is fully furred.[4] They have a robust skull morphology, with thick zygomatic arches and high sagittal crests. Their dental formula of 2.1.3.22.1.3.3. It is thought that their eyes are red or orange in color like other members of their genus. They lack tails. Males and females are similar in body size. [3]

Biology

One was observed roosting in a fig tree. They have been observed roosting alone and within groups.[2] Their diet is unknown, but specimens in museums have extensive tooth wearing, suggesting that they might feed on hard, abrasive fruits.[3]

Habitat and range

The majority of museum specimens were collected from cloud forests at 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) or higher above sea level.[3] It is not thought to occur in coastal forests.[2] It had not been seen on Bougainville Island since 1968, until they were again sighted in 2016.[1] It was last seen on Choiseul Island in 2008.[8]

Conservation

In 1992, this species was feared extinct because it had not been seen despite research expeditions in the area.[9] However, a research expedition in 1995 documented six individuals over the course of six months.[2] In 1992, captive breeding was recommended for this species, as its population was thought to be in drastic decline.[9] However, as of 2017, there is no evidence of such a program existing, or plans to initiate one. The species is on the IUCN Red List as an Endangered species. It is listed as endangered because it is thought that its population has declined by at least 50% from 1997-2017. Threats to this species include habitat destruction from agriculture. It is also hunted for bushmeat.[1] In 2013, Bat Conservation International listed this species as one of the 35 species of its worldwide priority list of conservation.[10] Efforts by Bat Conservation International to conserve the species include partnering with the indigenous Rotokas people, Volunteer Service Abroad, and the Bougainville Bureau for the Environment to develop a conservation plan for Kunua Plains & Mount Balbi Key Biodiversity Area. These efforts are intended to conserve the Bougainville monkey-faced bat and the greater monkey-faced bat.[11] Conservation actions identified by Bat Conservation International include identifying alternate protein sources for indigenous peoples so that they do not have to rely on bushmeat, creating native tree nurseries for reforestation efforts, mitigating conflicts between the fruit-eating bats and farmers seeking to protect their crops, and engaging the community more frequently in conservation dialogue. Researchers seeking to work in Kunua Plains & Mount Balbi Key Biodiversity Area will pay the Rotokas people for access to their land, hire guides and porters from local villages, and purchase their produce locally to provide income for the Rotokas people.[12]

References

- Helgen, K.; Hamilton, S.; Leary, T. & Bonaccorso, F. (2008). "Pteralopex anceps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Listed as Endangered B1ab(i,ii,iii,v).

- Bowen-Jones, E., Abrutat, D., Markham, B., & Bowe, S. (1997). Flying foxes on Choiseul (Solomon Islands)–the need for conservation action. Oryx, 31(3), 209-217.

- Helgen, K. M. (2005). Systematics of the Pacific monkey-faced bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae), with a new species of Pteralopex and a new Fijian genus. Systematics and Biodiversity, 3(4), 433-453.

- Andersen, K. (1909). XXXII.—Two new bats from the Solomon Islands. Journal of Natural History, 3(15), 266-270.

- Laurie, E. M., & Hill, J. E. (1954). List of land mammals of New Guinea, Celebes and adjacent islands 1758-1952. List of land mammals of New Guinea, Celebes and adjacent islands 1758-1952.

- Hill, J. E., & Beckon, W. N. (1978). A new species of Pteralopex Thomas, 1888 (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) from the Fiji Islands. British Museum (Natural History).

- Parnaby, H. E. (2001). A taxonomic review of the genus Pteralopex (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae), the monkey-faced bats of the south-western Pacific. Australian Mammalogy, 23(2), 145-162.

- Pikacha, P. 2008. Distribution, habitat preference, and conservation status of the endemic giant rats Solomys ponceleti and S. salebrosus on Choiseul Island, Solomon Islands. BP Conservation 2005 Final Report, Project no 700305. BP Conservation Leadership Programme.

- Mickleburgh, S. P., Hutson, A. M., & Racey, P. A. (1992). Old World fruit bats. An action plan for their conservation. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- "Annual Report 2013-2014" (PDF). batcon.org. Bat Conservation International. August 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- Jepson, Katie (November 1, 2016). "A Joint Effort to Save the Bougainville Monkey - Faced Bat". batcon.org. Bat Conservation International. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Conservation of Bougainville’s Endangered Monkey-faced Bats (PDF) (Report). Bat Conservation International. November 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.