Hammer-headed bat

The hammer-headed bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus), also known as hammer-headed fruit bat and big-lipped bat, is a megabat widely distributed in West and Central Africa. It is the only member of the genus Hypsignathus, which is part of the tribe Epomophorini along with four other genera. It is the largest bat in continental Africa, with wingspans approaching 1 m, or about 3 ft, and males almost twice as heavy as females. Males and females also greatly differ in appearance, making it the most sexually dimorphic bat species in the world. These differences include several adaptations that help males produce and amplify vocalizations: the males' larynges (vocal cords) are about three times as large as those of females, and they have large resonating chambers on their faces. Females appear more like a typical megabat, with foxlike faces.

| Hammer-headed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Pteropodidae |

| Genus: | Hypsignathus H. Allen, 1861 |

| Species: | H. monstrosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Hypsignathus monstrosus H. Allen, 1861 | |

| |

| Hammer-headed bat range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It is frugivorous, consuming a variety of fruits such as figs, bananas, and mangoes, though a few instances of carnivory have been noted. Females tend to travel a consistent route to find predictable fruits, whereas males travel more to find the highest quality fruit. It forages at night, sleeping during the day in tree roosts. Individuals may roost alone or in small groups. Unlike many other bat species that segregate based on sex, males and females will roost together during the day. It has two mating seasons each year during the dry seasons. It is believed to be the only bat species with a classical lek mating system, wherein males gather on a "lek", which in this case is a long and thin stretch of land, such as along a river. There, they produce loud, honking vocalizations to attract females. Females visit the lek and select a male to mate with; the most successful 6% of males are involved in 79% of matings. Offspring are born five or six months later, typically a singleton, though twins have been documented. Its predators are not well-known, but may include hawks. Adults are commonly affected by parasites such as flies and mites.

The hammer-headed bat is sometimes considered a pest due to its frugivorous diet and its extremely loud honking noises at night. In Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it is consumed as bushmeat. It has been investigated as a potential reservoir of the Ebola virus, with several testing positive for antibodies against the virus. It is not considered a species of conservation concern due to its large range and presumably large population size.

Taxonomy and etymology

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position of Hypsignathus within Pteropodidae[2] |

The hammer-headed bat was described as a new species in 1861 by American scientist Harrison Allen. Allen placed the species into a newly-created genus, Hypsignathus.[3] The holotype had been collected by French-American zoologist Paul Du Chaillu[3] in Gabon.[4] The genus name Hypsignathus comes from Ancient Greek "húpsos" meaning "high" and "gnáthos" meaning "jaw." T. S. Palmer speculated that Allen chose the name Hypsignathus to allude to the "deeply arched mouth" of the species.[5] The species name "monstrosus" is Latin for "having the qualities of a monster."[6]

A 2011 study found that Hypsignathus was the most basal member of the tribe Epomophorini, which also includes Epomops, Micropteropus, Epomophorus, and Nanonycteris.[2] Initially, Allen identified the hammer-headed bat as a member of the subfamily Pteropodinae of the megabats.[3] However, in 1997, Epomophorini was recognized as part of the subfamily Epomophorinae.[7] Some taxonomists do not recognize Epomophorinae as a valid subfamily and include its taxa, including the Epomophorini, within Rousettinae.[8][9]

Description

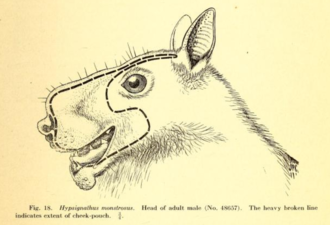

The hammer-headed bat is the largest bat in mainland Africa.[10] Males have wingspans up to 90.1 cm (2.96 ft),[11] and all individuals have forearm lengths exceeding 112 mm (4.4 in).[10] It has pronounced sexual dimorphism, more so than any other bat species in the world,[10] with males up to twice as heavy as females. The average weight of males is 420 g (15 oz), compared to 234 g (8.3 oz) for females.[11] Other differences between the sexes relate to their social system, in which males produce loud, honking vocalizations. Therefore, males have greatly enlarged larynges, about three times the size of females',[12] extending through most of the thoracic cavity, and measuring half the length of the spine. The larynx is so large, it displaces other organs, including the heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract.[12] Males also have resonating chambers to increase the volume of sound production. These chambers are pharyngeal air sacs connected to a large sinus in the humped snout.[10] These numerous adaptations caused scientists Herbert Lang and James Chapin to remark, "In no other mammal is everything so entirely subordinated to the organs of voice".[13]

Males overall have boxy heads with enormous lips, while the females, with their narrower snouts, have more foxlike faces.[12] Males and females both have dark brown fur, with a paler mantle (sides and back of neck). It has patches of white fur at the base of the ears, though sometimes indistinct. The fur is long and smooth, though somewhat woolly in texture on the mantle. The ears are triangular and blackish-brown, and the eyes are very large.[10] The dental formula is 2.1.2.12.1.3.2 for a total of 28 teeth; very occasionally, individuals have been found with an additional upper premolar on each side of the mouth, for a total of 30 teeth. The skull is larger and more robust than any other megabat in Africa, with a pronounced, massive snout. The tongue is large and powerful, with an expanded, tridentate tip. The tongue has backwards-facing papillae used to extract juice from fruits.[10]

The wings are characterized by low aspect ratio, meaning that it has a smaller wingspan relative to the wing area. The wing loading is considered exceptionally high, meaning that it has a large body weight relative to the wing area. The wings are blackish brown in color.[10] The thumb is approximately 128–137 mm (5.0–5.4 in) long.[12] The wings attach to the hindlimbs at the second toe. It lacks a tail.[10]

Instead of the typical mammalian karyotype where females have two X chromosomes and males have one each of X and Y, males have a single X chromosome and no Y chromosome, known as X0 sex-determination system.[10] Thus, females have 36 chromosomes (34 autosomes and two sex chromosomes), and males have 35 chromosomes (34 autosomes but only one sex chromosome).[14] This is seen in a few other bat genera, including Epomophorus and Epomops.[15][16]

Biology and ecology

Diet and foraging

Hammer-headed bats are frugivores. Figs make up much of their diet, but mangos, bananas and guavas may also be consumed. There are some complications inherent in a fruit diet such as insufficient protein intake. It is suggested that fruit bats compensate for this by possessing a proportionally longer intestine compared to insectivorous species.[12] There have been anecdotes of the species killing and eating chickens, or consuming scraps of meat from bird carcasses left by humans.[13][10]

Males and females rely on different strategies for foraging. Females use trap-lining, in which they travel an established route with dependable and predictable food sources, even if the food is lower quality. Males, in contrast, search for areas rich with food, traveling up to 10 km (6.2 mi) to reach particularly good food patches.[12] Upon finding suitable fruit, the hammer-headed bat may eat at the tree or pick the fruit and carry it away to another site for consumption. It chews the fruit, swallowing the juice and soft pulp, before spitting out the rest.[12] The guano (feces) typically contains seeds from ingested fruits, indicating that it may be an important seed disperser.[10]

Reproduction

Little is known about reproduction in hammer-headed bats. In some populations, breeding is thought to take place semi-annually during the dry seasons. The timing of the dry season varies depending on the locality, but in general the first breeding season is from June to August and the second is from December to February. Females may become pregnant up to twice per year, giving birth after five or six months gestation[10] to one offspring at a time,[12] though twins have been reported.[13] Newborns weigh approximately 40 g (1.4 oz) at birth.[13] Females reach sexual maturity faster than males, and can reproduce at six months. Females reach adult size by nine months of age. In contrast, males are not sexually mature until eighteen months. Males and females are similar in size for their first year of life.[12]

This species is often cited as an example of classical lek mating,[17] and is perhaps the only bat species with such.[18] The classical lek is defined by four criteria:[10]

- Males gather in a particular region, known as a lek; here, they establish "display territories"

- Display territories offer no beneficial resources to females beyond access to males

- Mate choice is up to females to decide; all copulation occurs at the lek

- Males do not assist females in caring for offspring

Males form these leks along streams or riverbeds during the mating season, which lasts 1–3 months.[12] Leks consist of 20–135 males in an area about 40 m (130 ft) wide and 400–1,600 m (1,300–5,200 ft) long.[10] Each male claims a display territory of about 10 m (33 ft) in diameter,[11] in which he honks repeatedly and flaps his wings while hanging from a branch.[12] Typically, 60–120 honks are produced per minute.[17] Males display for around four hours before foraging, with peaks in lekking activity in the early evening and before dawn. The early evening peak is when the majority of copulation occurs. Females will fly through the lek, selecting a male by landing on a branch next to him. The chosen male emits a "staccato buzz" call, followed immediately by copulation, which lasts 30–60 seconds.[12] After copulation, the female immediately departs, and the male resumes displaying.[10] The males at the center of the lek have the most success, and are responsible for the majority of matings:[12] the top 6% of males have 79% of the total matings.[10] In the before-dawn peak in activity, copulation is less frequent, and males spend time jockeying with each other for the best display territory. As the mating season progresses, the importance of the before-dawn peak lessens.[12]

However, some populations of hammer-headed bats in West Africa do not use leks. Instead, they have a harem system.[19]

Behavior

During the day, the hammer-headed bat roosts in trees, typically 20–30 m (66–98 ft) above the ground in the forest canopy. Various trees are used for roosting, with no preference for a particular species. It has low fidelity to its roost and will move to a new roost after 5–9 days.[10] It relies on camouflage to hide them from predators.[12] It displays a mix of solitary and social behavior. Individuals of both sexes are frequently found roosting alone, though they may roost in small groups of around four individuals. Occasionally, groups of up to twenty-five have been documented. Groups are of mixed sex and age, unlike other bat species which segregate based on sex. While roosting, individuals in a group are approximately 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) apart, with males on the periphery and females nearer the center.[10] During most of the day, individuals sleep with their noses covered by their wings.[17] Members of the same group show little interaction with each other: they do not "squabble", vocalize, or groom each other. Instead, at sunset, individuals groom themselves then set off independently to forage.[10]

Predators and parasites

Its predators are not well-documented, but may include avian species such as the long-tailed hawk.[20] It has a diverse array of parasites, including such ectoparasites as the bat fly (Nycteribiidae) Dipseliopoda arcuata, the spinturnicid mite Ancystropus aethiopicus, the gastronyssid mite Mycteronyssus polli, and the teinocoptid mite Teinocopties auricularis.[10] Internally, it is known to be affected by the liver parasite Hepatocystis carpenteri. Adults commonly host parasites.[12]

Range and habitat

The hammer-headed bat is a lowland species, always occurring below 1,800 m (5,900 ft) above sea level.[12] Most records of this species occur in rainforest habitat, including lowland rainforest, swamp forest, riverine forests, and mosaics of forest and grassland. While it has been documented in savanna habitats, these records are rare, and it has been speculated that these individuals are vagrants.[10] It has a wide range in West and Central Africa, including the following countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Togo, and Uganda.[1]

Interactions with humans

As pests and bushmeat

As a frugivorous species, the hammer-headed bat is sometimes considered a pest of fruit crops.[21] Its ability to produce extremely loud vocalizations means that some consider it one of Africa's most significant nocturnal pests.[10] Humans hunt this large bat and consume it as bushmeat.[21] It is eaten in Nigeria,[22] as well as seasonally in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[23]

Disease transmission

The hammer-headed bat has been investigated as a potential reservoir of the Ebola virus. Some individuals have tested seropositive for the virus, meaning that they had antibodies against the virus, though the virus itself was not detected. Additionally, nucleic acid sequences associated with the virus have been isolated from its tissues.[24] However, the natural reservoirs of ebolaviruses are still unknown as of 2019.[25][26][27] Megabats like the hammer-headed bat tend to be over-sampled relative to other potential Ebola virus hosts, meaning that they may have an unwarranted amount of research attention, and as of 2015, no bat hunter or researcher is known to be the index case ("patient zero") in an Ebola outbreak.[28]

Conservation

As of 2016, it is evaluated as a least-concern species by the IUCN—its lowest conservation priority. It meets the criteria for this classification because it has a wide geographic range; its population is presumably large; and it is not thought to be experiencing rapid population decline.[1] It is not a common bat species in captivity, though it is kept at the Wrocław Zoo in Poland as of 2020,[29] and was kept at the Bronx Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park in the 1970s and 1980s. In captivity, it is vulnerable to stress-related illness, particularly males.[30]

References

- Tanshi, I. (2016). "Hypsignathus monstrosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T10734A115098825.

- Almeida, Francisca C; Giannini, Norberto P; Desalle, Rob; Simmons, Nancy B (2011). "Evolutionary relationships of the old world fruit bats (Chiroptera, Pteropodidae): Another star phylogeny?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11: 281. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-281. PMC 3199269. PMID 21961908.

- Allen, H. (1861). "Description of new pteropine bats from Africa". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 13: 156–158.

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Palmer, T.S. (1904). "Index of Genera and Subgenera". North American Fauna (23): 343.

- Wheeler, W. A. (1872). A Dictionary of the English Language, Explanatory, Pronouncing Etymological, and Synonymous, with Copious Appendix. G & C Merriam.

- Bergmans, W. (1997). "Taxonomy and biogeography of African fruit bats (Mammalia, Megachiroptera). 5. The genera Ussonycteris Andersen, 1912, Myonycteris Matschie, 1899 and Megaloglossus Pagenstecher, 1885; general remarks and conclusions; annex: key to all species". Beaufortia. 47 (2): 11–90.

- Amador, Lucila I.; Moyers Arévalo, R. Leticia; Almeida, Francisca C.; Catalano, Santiago A.; Giannini, Norberto P. (2018). "Bat Systematics in the Light of Unconstrained Analyses of a Comprehensive Molecular Supermatrix". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25: 37–70. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9363-8.

- Cunhaalmeida, Francisca; Giannini, Norberto Pedro; Simmons, Nancy B. (2016). "The Evolutionary History of the African Fruit Bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)". Acta Chiropterologica. 18: 73–90. doi:10.3161/15081109ACC2016.18.1.003.

- Happold, M. (2013). Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. 4. A&C Black. p. 259–262. ISBN 9781408189962.

- Nowak, M., R. (1994). Walker's Bats of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 63–64.

- Langevin, P.; Barclay, R. (1990). "Hypsignathus monstrosus". Mammalian Species. 357 (357): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3504110. JSTOR 3504110.

- Nowak, M., R. (1999). Walker's Bats of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- Hsu, T. C.; Benirschke, Kurt (1977). "Hypsignathus monstrosus (Hammer-headed fruit bat)". An Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. pp. 13–16. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-6436-2_4. ISBN 978-1-4684-7997-3.

- Primus, Ashley; Harvey, Jessica; Guimondou, Sylvain; Mboumba, Serge; Ngangui, Raphaël; Hoffman, Federico; Baker, Robert; Porter, Calvin A. (2006). "Karyology and Chromosomal Evolution of Some Small Mammals Inhabiting the Rainforest of the Rabi Oil Field, Gabon" (PDF). Bulletin of the Biological Society of Washingto (12): 371–382.

- Denys, C.; Kadjo, B.; Missoup, A. D.; Monadjem, A.; Aniskine, V. (2013). "New records of bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) and karyotypes from Guinean Mount Nimba (West Africa)". Italian Journal of Zoology. 80 (2): 279–290. doi:10.1080/11250003.2013.775367. hdl:2263/42399.

- Bradbury, Jack W. (1977). "Lek Mating Behavior in the Hammer-headed Bat". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 45 (3): 225–255. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1977.tb02120.x.

- Toth, C. A.; Parsons, S. (2013). "Is lek breeding rare in bats?". Journal of Zoology. 291: 3–11. doi:10.1111/jzo.12069.

- Olson, Sarah H.; Bounga, Gerard; Ondzie, Alain; Bushmaker, Trent; Seifert, Stephanie N.; Kuisma, Eeva; Taylor, Dylan W.; Munster, Vincent J.; Walzer, Chris (2019). "Lek-associated movement of a putative Ebolavirus reservoir, the hammer-headed fruit bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus), in northern Republic of Congo". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223139. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223139. PMC 6772046. PMID 31574111.

- Neil, Emily (2018). "First sighting of a long-tailed hawk attacking a hammer-headed fruit bat". African Journal of Ecology. 56: 131. doi:10.1111/aje.12419.

- "Hammer-headed Fruit Bat". BATS Magazine. Vol. 34 no. 1. 2015.

- Mildenstein, T.; Tanshi, I.; Racey, P. A. (2016). "Exploitation of Bats for Bushmeat and Medicine". Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World. Springer. p. 327. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25220-9_12. ISBN 978-3-319-25218-6.

- Mickleburgh, Simon; Waylen, Kerry; Racey, Paul (2009). "Bats as bushmeat: A global review". Oryx. 43 (2): 217. doi:10.1017/S0030605308000938.

- Gonzalez, E.; Gonzalez, J. P.; Pourrut, X. (2007). "Ebolavirus and Other Filoviruses". Wildlife and Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: The Biology, Circumstances and Consequences of Cross-Species Transmission. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 315. pp. 363–387. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_15. ISBN 978-3-540-70961-9. PMC 7121322. PMID 17848072.

- "What is Ebola Virus Disease?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

Scientists do not know where Ebola virus comes from.

- Rewar, Suresh; Mirdha, Dashrath (2015). "Transmission of Ebola Virus Disease: An Overview". Annals of Global Health. 80 (6): 444–51. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.02.005. PMID 25960093.

Despite concerted investigative efforts, the natural reservoir of the virus is unknown.

- Baseler, Laura; Chertow, Daniel S.; Johnson, Karl M.; Feldmann, Heinz; Morens, David M. (2017). "The Pathogenesis of Ebola Virus Disease". Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 12: 387–418. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100506. PMID 27959626.

The geographic ranges of many animal species, including bats, squirrels, mice and rats, dormice, and shrews, match or overlap with known outbreak sites of African filoviruses, but none of these mammals has yet been universally accepted as an EBOV reservoir.

- Leendertz, Siv Aina J.; Gogarten, Jan F.; Düx, Ariane; Calvignac-Spencer, Sebastien; Leendertz, Fabian H. (2016). "Assessing the Evidence Supporting Fruit Bats as the Primary Reservoirs for Ebola Viruses". Ecohealth. 13 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1007/s10393-015-1053-0. PMC 7088038. PMID 26268210.

- "A new species in the ZOO Wrocław. It's a flying moose, or ... a bat". Tu Wrocław. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- MacNamara, Mark C.; Doherty, James G.; Viola, Stephen; Schacter, AMY (1980). "The management and breeding of Hammer-headed bats Hypsignathus monstrosus at the New York Zoological Park". International Zoo Yearbook. 20: 260–264. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1980.tb00988.x.

External links

- "Hunting for Ebola among the bats of the Congo", a four-minute video from Science Magazine

- Audio recording of a few males honking in the early evening at their lek

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hypsignathus monstrosus. |