Jules Massenet

Jules Émile Frédéric Massenet (French pronunciation: [ʒyl emil fʁedeʁik masnɛ];[n 1] 12 May 1842 – 13 August 1912) was a French composer of the Romantic era best known for his operas, of which he wrote more than thirty. The two most frequently staged are Manon (1884) and Werther (1892). He also composed oratorios, ballets, orchestral works, incidental music, piano pieces, songs and other music.

While still a schoolboy, Massenet was admitted to France's principal music college, the Paris Conservatoire. There he studied under Ambroise Thomas, whom he greatly admired. After winning the country's top musical prize, the Prix de Rome, in 1863, he composed prolifically in many genres, but quickly became best known for his operas. Between 1867 and his death forty-five years later he wrote more than forty stage works in a wide variety of styles, from opéra-comique to grand-scale depictions of classical myths, romantic comedies, lyric dramas, as well as oratorios, cantatas and ballets. Massenet had a good sense of the theatre and of what would succeed with the Parisian public. Despite some miscalculations, he produced a series of successes that made him the leading composer of opera in France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Like many prominent French composers of the period, Massenet became a professor at the Conservatoire. He taught composition there from 1878 until 1896, when he resigned after the death of the director, Ambroise Thomas. Among his students were Gustave Charpentier, Ernest Chausson, Reynaldo Hahn and Gabriel Pierné.

By the time of his death, Massenet was regarded by many critics as old-fashioned and unadventurous although his two best-known operas remained popular in France and abroad. After a few decades of neglect, his works began to be favourably reassessed during the mid-20th century, and many of them have since been staged and recorded. Although critics do not rank him among the handful of outstanding operatic geniuses such as Mozart, Verdi and Wagner, his operas are now widely accepted as well-crafted and intelligent products of the Belle Époque.

Biography

Early years

Massenet was born on 12 May 1842 at Montaud, then an outlying hamlet and now a part of the city of Saint-Étienne, in the Loire.[6] He was the youngest of the four children of Alexis Massenet (1788–1863) and his second wife Eléonore-Adelaïde née Royer de Marancour (1809–1875); the elder children were Julie, Léon and Edmond.[n 2] Massenet senior was a prosperous ironmonger; his wife was a talented amateur musician who gave Jules his first piano lessons. By early 1848 the family had moved to Paris, where they settled in a flat in Saint-Germain-des-Prés.[8] Massenet was educated at the Lycée Saint-Louis and, from either 1851 or 1853, the Paris Conservatoire. According to his colourful but unreliable memoirs,[9] Massenet auditioned in October 1851, when he was nine, before a judging panel comprising Daniel Auber, Fromental Halévy, Ambroise Thomas and Michele Carafa, and was admitted at once.[10] His biographer Demar Irvine dates the audition and admission as January 1853.[11] Both sources agree that Massenet continued his general education at the lycée in tandem with his musical studies.[12]

At the Conservatoire Massenet studied solfège with Augustin Savard and the piano with François Laurent.[13] He pursued his studies, with modest distinction, until the beginning of 1855, when family concerns disrupted his education. Alexis Massenet's health was poor, and on medical advice he moved from Paris to Chambéry in the south of France; the family, including Massenet, moved with him. Again, Massenet's own memoirs and the researches of his biographers are at variance: the composer recalled his exile in Chambéry as lasting for two years; Henry Finck and Irvine record that the young man returned to Paris and the Conservatoire in October 1855.[14] On his return he lodged with relations in Montmartre and resumed his studies; by 1859 he had progressed so far as to win the Conservatoire's top prize for pianists.[15] The family's finances were no longer comfortable, and to support himself Massenet took private piano students and played as a percussionist in theatre orchestras.[16] His work in the orchestra pit gave him a good working knowledge of the operas of Gounod and other composers, classic and contemporary.[17] Traditionally, many students at the Conservatoire went on to substantial careers as church organists; with that in mind Massenet enrolled for organ classes, but they were not a success and he quickly abandoned the instrument. He gained some work as a piano accompanist, in the course of which he met Wagner who, along with Berlioz, was one of his two musical heroes.[n 3]

In 1861 Massenet's music was published for the first time, the Grande Fantasie de Concert sur le Pardon de Ploërmel de Meyerbeer , a virtuoso piano work in nine sections.[19] Having graduated to the composition class under Ambroise Thomas, Massenet was entered for the Conservatoire's top musical honour, the Prix de Rome, previous winners of which included Berlioz, Thomas, Gounod and Bizet. The first two of these were on the judging panel for the 1863 competition.[n 4] All the competitors had to set the same text by Gustave Chouquet, a cantata about David Rizzio; after all the settings had been performed Massenet came face to face with the judges. He recalled:

Ambroise Thomas, my beloved master, came towards me and said, "Embrace Berlioz, you owe him a great deal for your prize." "The prize," I cried, bewildered, my face shining with joy. "I have the prize!!!" I was deeply moved and I embraced Berlioz, then my master, and finally Monsieur Auber. Monsieur Auber comforted me. Did I need comforting? Then he said to Berlioz pointing to me, "He'll go far, the young rascal, when he's had less experience!"[21][n 5]

The prize brought a well-subsidised three-year period of study, two-thirds of which was spent at the French Academy in Rome, based at the Villa Medici. At that time the academy was dominated by painters rather than musicians; Massenet enjoyed his time there, and made lifelong friendships with, among others, the sculptor Alexandre Falguière and the painter Carolus-Duran, but the musical benefit he derived was largely self-taught.[24] He absorbed the music at St Peter's, and closely studied the works of the great German masters, from Handel and Bach to contemporary composers.[24] During his time in Rome, Massenet met Franz Liszt, at whose request he gave piano lessons to Louise-Constance "Ninon" de Gressy, the daughter of one of Liszt's rich patrons. Massenet and Ninon fell in love, but marriage was out of the question while he was a student with modest means.[25]

Early works

Massenet returned to Paris in 1866. He made a living by teaching the piano and publishing songs, piano pieces and orchestral suites, all in the popular style of the day.[17] Prix de Rome winners were sometimes invited by the Opéra-Comique in Paris to compose a work for performance there. At Thomas's instigation, Massenet was commissioned to write a one-act opéra comique, La grand'tante, presented in April 1867.[26] At around the same time he composed a Requiem, which has not survived.[27] In 1868 he met Georges Hartmann, who became his publisher and was his mentor for twenty-five years; Hartmann's journalistic contacts did much to promote his protégé's reputation.[17][n 6]

In October 1866 Massenet and Ninon were married; their only child, Juliette, was born in 1868. Massenet's musical career was briefly interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, during which he served as a volunteer in the National Guard alongside his friend Bizet.[17] He found the war so "utterly terrible" that he refused to write about it in his memoirs.[29] He and his family were trapped in the Siege of Paris but managed to get out before the Paris Commune began; the family stayed for some months in Bayonne, in southwestern France.[30]

After order was restored, Massenet returned to Paris where he completed his first large-scale stage work, an opéra comique in four acts, Don César de Bazan (Paris, 1872). It was a failure, but in 1873 he succeeded with his incidental music to Leconte de Lisle's tragedy Les Érinnyes and with the dramatic oratorio, Marie-Magdeleine, both of which were performed at the Théâtre de l'Odéon.[27] His reputation as a composer was growing, but at this stage he earned most of his income from teaching, giving lessons for six hours a day.[31]

Massenet was a prolific composer; he put this down to his way of working, rising early and composing from four o'clock in the morning until midday, a practice he maintained all his life.[31] In general he worked fluently, seldom revising, although Le roi de Lahore, his nearest approach to a traditional grand opera, took him several years to complete to his own satisfaction.[17] It was finished in 1877 and was one of the first new works to be staged at the Palais Garnier, opened two years previously.[32] The opera, with a story taken from the Mahabharata, was a success and was quickly taken up by the opera houses of eight Italian cities. It was also performed at the Hungarian State Opera House, the Bavarian State Opera, the Semperoper in Dresden, the Teatro Real in Madrid, and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in London.[33] After the first Covent Garden performance, The Times summed the piece up in a way that was frequently to be applied to the composer's operas: "M. Massenet's opera, although not a work of genius proper, is one of more than common merit, and contains all the elements of at least temporary success."[34]

This period was an early high point in Massenet's career. He had been made a chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1876, and in 1878 he was appointed professor of counterpoint, fugue and composition at the Conservatoire under Thomas, who was now the director.[27][n 7] In the same year he was elected to the Institut de France, a prestigious honour, rare for a man in his thirties. Camille Saint-Saëns, whom Massenet beat in the election for the vacancy, was resentful at being passed over for a younger composer. When the result of the election was announced, Massenet sent Saint-Saëns a courteous telegram: "My dear colleague: the Institut has just committed a great injustice". Saint-Saëns cabled back, "I quite agree." He was elected three years later, but his relations with Massenet remained cool.[9][37]

Massenet was a popular and respected teacher at the Conservatoire. His pupils included Bruneau, Charpentier, Chausson, Hahn, Leroux, Pierné, Rabaud and Vidal.[27] He was known for the care he took in drawing out his pupils' ideas, never trying to impose his own.[9][n 8] One of his last students, Charles Koechlin, recalled Massenet as a voluble professor, dispensing "a teaching active, living, vibrant, and moreover comprehensive".[38] According to some writers, Massenet's influence extended beyond his own students. In the view of the critic Rodney Milnes, "In word-setting alone, all French musicians profited from the freedom he won from earlier restrictions."[9] Romain Rolland and Francis Poulenc have both considered Massenet an influence on Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande;[9] Debussy was a student at the Conservatoire during Massenet's professorship but did not study under him.[n 9]

Operatic successes and failures, 1879–96

Massenet's growing reputation did not prevent a contretemps with the Paris Opéra in 1879. Auguste Vaucorbeil, director of the Opéra, refused to stage the composer's new piece, Hérodiade, judging the libretto either improper or inadequate.[n 10] Édouard-Fortuné Calabresi, joint director of the Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels, immediately offered to present the work, and its première, lavishly staged, was given in December 1881. It ran for fifty-five performances in Brussels, and had its Italian premiere two months later at La Scala. The work finally reached Paris in February 1884, by which time Massenet had established himself as the leading French opera composer of his generation.[41]

Manon, first given at the Opéra-Comique in January 1884, was a prodigious success and was followed by productions at major opera houses in Europe and the United States. Together with Gounod's Faust and Bizet's Carmen it became, and has remained, one of the cornerstones of the French operatic repertoire.[42] After the intimate drama of Manon, Massenet once more turned to opera on the grand scale with Le Cid in 1885, which marked his return to the Opéra. The Paris correspondent of The New York Times wrote that with this new work Massenet "has resolutely declared himself a melodist of undoubted consistency and of remarkable inspiration."[43] After these two triumphs, Massenet entered a period of mixed fortunes. He worked on Werther intermittently for several years, but it was rejected by the Opéra-Comique as too gloomy.[44][n 11] In 1887 he met the American soprano Sibyl Sanderson. He developed passionate feelings for her, which remained platonic, although it was widely believed in Paris that she was his mistress, as caricatures in the journals hinted with varying degrees of subtlety.[46] For her, the composer revised Manon and wrote Esclarmonde (1889). The latter was a success, but it was followed by Le mage (1891), which failed. Massenet did not complete his next project, Amadis, and it was not until 1892 that he recovered his earlier successful form. Werther received its first performance in February 1892, when the Vienna Hofoper asked for a new piece, following the enthusiastic reception of the Austrian premiere of Manon.[9]

Though in the view of some writers Werther is the composer's masterpiece,[42][47] it was not immediately taken up with the same keenness as Manon. The first performance in Paris was in January 1893 by the Opéra-Comique company at the Théâtre Lyrique, and there were performances in the United States, Italy and Britain, but it met with a muted response. The New York Times said of it, "If M. Massenet's opera does not have lasting success it will be because it has no genuine depth. Perhaps M. Massenet is not capable of achieving profound depths of tragic passion; but certainly he will never do so in a work like Werther".[48] It was not until a revival by the Opéra-Comique in 1903 that the work became an established favourite.[44]

Thaïs (1894), composed for Sanderson, was moderately received.[49] Like Werther, it did not gain widespread popularity among French opera-goers until its first revival, which was four years after the premiere, by when the composer's association with Sanderson was over.[9] In the same year he had a modest success in Paris with the one-act Le portrait de Manon at the Opéra-Comique, and a much greater one in London with La Navarraise at Covent Garden.[50] The Times commented that in this piece Massenet had adopted the verismo style of such works as Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana to great effect. The audience clamoured for the composer to acknowledge the applause, but Massenet, always a shy man, declined to take even a single curtain call.[51]

Later years, 1896–1912

The death of Ambroise Thomas in February 1896 made vacant the post of director of the Conservatoire. The French government announced on 6 May that Massenet had been offered the position and had refused it.[52] The following day it was announced that another faculty member, Théodore Dubois, had been appointed director, and Massenet had resigned as professor of composition.[53] Two explanations have been advanced for this sequence of events. Massenet wrote in 1910 that he had remained in post as professor out of loyalty to Thomas, and was eager to abandon all academic work in favour of composing, a statement repeated by his biographers Hugh Macdonald and Demar Irvine.[17][54] Other writers on French music have written that Massenet was intensely ambitious to succeed Thomas, but resigned in pique after three months of manoeuvring, once the authorities finally rejected his insistence on being appointed director for life, as Thomas had been.[55] He was succeeded as professor by Gabriel Fauré, who was doubtful of Massenet's credentials, considering his popular style to be "based on a generally cynical view of art".[56]

With Grisélidis and Cendrillon complete, though still awaiting performance, Massenet began work on Sapho, based on a novel by Daudet about the love of an innocent young man from the country for a worldly-wise Parisienne.[57] It was given at the Opéra-Comique in November 1897, with great success, though it has been neglected since the composer's death.[58] His next work staged there was Cendrillon, his version of the Cinderella story, which was well received in May 1899.[59]

Macdonald comments that at the start of the 20th century Massenet was in the enviable position of having his works included in every season of the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique, and in opera houses around the world.[17] From 1900 to his death he led a life of steady work and, generally, success. According to his memoirs, he declined a second offer of the directorship of the Conservatoire in 1905.[60][n 12] Apart from composition, his main concern was his home life in the rue de Vaugirard, Paris, and at his country house in Égreville. He was uninterested in Parisian society, and so shunned the limelight that in later life he preferred not to attend his own first nights.[63] He described himself as "a fireside man, a bourgeois artist".[64] The main biographical detail of note of his latter years was his second amitié amoureuse with one of his leading ladies, Lucy Arbell, who created roles in his last operas.[n 13] Milnes describes Arbell as "gold-digging": her blatant exploitation of the composer's honourable affections caused his wife considerable distress and even strained Massenet's devotion (or infatuation as Milnes characterises it).[9] After the composer's death Arbell pursued his widow and publishers through the law courts, seeking to secure herself a monopoly of the leading roles in several of his late operas.[9]

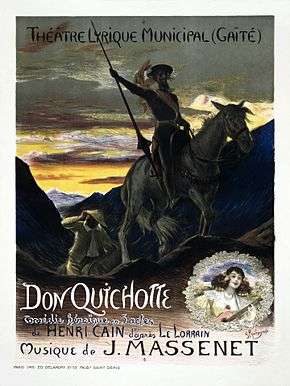

A rare excursion from the opera house came in 1903 with Massenet's only piano concerto, on which he had begun work while still a student. The work was performed by Louis Diémer at the Conservatoire, but made little impression compared with his operas.[66] In 1905 Massenet composed Chérubin, a light comedy about the later career of the sex-mad pageboy Cherubino from Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro.[67] Then came two serious operas, Ariane, on the Greek legend of Theseus and Ariadne, and Thérèse, a terse drama set in the French Revolution.[68] His last major success was Don Quichotte (1910), which L'Etoile called "a very Parisian evening and, naturally, a very Parisian triumph".[n 14] Even with his creative powers seemingly in decline he wrote four other operas in his later years – Bacchus, Roma, Panurge and Cléopâtre. The last two, like Amadis, which he had been unable to finish in the 1890s, were premiered after the composer's death and then lapsed into oblivion.[17]

In August 1912 Massenet went to Paris from his house at Égreville to see his doctor. The composer had been suffering from abdominal cancer for some months, but his symptoms did not seem imminently life-threatening. Within a few days his condition deteriorated sharply. His wife and family hastened to Paris, and were with him when he died, aged seventy. By his own wish his funeral, with no music, was held privately at Égreville, where he is buried in the churchyard.[70][71]

Music

Background

In the view of his biographer Hugh Macdonald, Massenet's main influences were Gounod and Thomas, with Meyerbeer and Berlioz also important to his style.[17] From beyond France he absorbed some traits from Verdi, and possibly Mascagni, and above all Wagner. Unlike some other French composers of the period, Massenet never fell fully under Wagner's spell, but he took from the earlier composer a richness of orchestration and a fluency in treatment of musical themes.[9]

Although when he chose, Massenet could write noisy and dissonant scenes – in 1885 Bernard Shaw called him "one of the loudest of modern composers"[72] – much of his music is soft and delicate. Hostile critics have seized on this characteristic,[27] but the article on Massenet in the 2001 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians observes that in the best of his operas this sensual side "is balanced by strong dramatic tension (as in Werther), theatrical action (as in Thérèse), scenic diversion (as in Esclarmonde), or humour (as in Le portrait de Manon)."[17]

Massenet's Parisian audiences were greatly attracted by the exotic in music, and Massenet willingly obliged, with musical evocations of far-flung places or times long past. Macdonald lists a great number of locales depicted in the operas, from ancient Egypt, mythical Greece and biblical Galilee to Renaissance Spain, India and Revolutionary Paris. Massenet's practical experience in orchestra pits as a young man and his careful training at the Conservatoire equipped him to make such effects without much recourse to unusual instruments. He understood the capabilities of his singers, and composed with close, detailed regard for their voices.[9][17]

Operas

Massenet wrote more than thirty operas. Authorities differ on the exact total because some of the works, particularly from his early years, are lost and others were left incomplete. Still others, such as Don César de Bazan and Le roi de Lahore, were substantially recomposed after their first productions and exist in two or more versions. Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians lists forty Massenet operas in all, of which nine are shown as lost or destroyed.[17] The "OperaGlass" website of Stanford University shows revised versions as premieres, and The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, does not: their totals are forty-four and thirty-six respectively.[9][73]

Having honed his personal style as a young man, and sticking broadly with it for the rest of his career, Massenet does not, as some other composers do, lend himself to classification into clearly defined early, middle and late periods. Moreover, his versatility means that there is no plot or locale that can be regarded as typical Massenet. Another respect in which he differed from many opera composers is that he did not work regularly with the same librettists: Grove lists more than thirty writers who provided him with librettos.[17]

The 1954 (fifth) edition of Grove said of Massenet, "to have heard Manon is to have heard the whole of him".[74] In 1994 Andrew Porter called this view preposterous. He countered, "Who knows Manon, Werther and Don Quichotte knows the best of Massenet, but not his range from heroic romance to steamy verismo."[75] Massenet's output covered most of the different subgenres of opera, from opérette (L'adorable Bel'-Boul and L'écureuil du déshonneur – both early pieces, the latter lost) and opéra-comique such as Manon, to grand opera – Grove categorises Le roi de Lahore as "the last grand opera to have a great and widespread success". Many of the elements of traditional grand opera are written into later large-scale works such as Le mage and Hérodiade.[17] Massenet's operas consist of anything from one to five acts, and although many of them are described on the title pages of their scores as "opéra" or "opéra comique", others have carefully nuanced descriptions such as "comédie chantée", "comédie lyrique", "comédie-héroïque", "conte de fées", "drame passionnel", "haulte farce musicale", "opéra légendaire", "opéra romanesque" and "opéra tragique".[76]

In some of his operas, such as Esclarmonde and Le mage, Massenet moved away from the traditional French pattern of free-standing arias and duets. Solos meld from declamatory passages into more melodic form, in a way that many contemporary critics thought Wagnerian. Shaw was not among them: in 1885 he wrote of Manon:

Of Wagnerism there is not the faintest suggestion. A phrase which occurs in the first love duet breaks out once or twice in subsequent amorous episodes, and has been seized on by a few unwary critics as a Wagnerian leit motif. But if Wagner had never existed, Manon would have been composed much as it stands now, whereas if Meyerbeer and Gounod had not made a path for M. Massenet, it is impossible to say whither he might have wandered, or how far he could have pushed his way.[77]

The 21st-century critic Anne Feeney comments, "Massenet rarely repeated musical phrases, let alone used recurrent themes, so the resemblance [to Wagner] lies solely in the declamatory lyricism and enthusiastic use of the brass and percussion."[78] Massenet enjoyed introducing comedy into his serious works, and writing some mainly comic operas. In Macdonald's view of the comic works, Cendrillon and Don Quichotte succeed, but Don César de Bazan and Panurge are less satisfying than "the more delicately tuned operas such as Manon, Le portrait de Manon and Le jongleur de Notre-Dame, where comedy serves a more complex purpose."[17]

According to Operabase, analysis of productions around the world in 2012–13 shows Massenet as the twentieth most popular of all opera composers, and the fourth most popular French one, after Bizet, Offenbach and Gounod.[79] The most often performed of his operas in the period are shown as Werther (63 productions in all countries), followed by Manon (47), Don Quichotte (22), Thaïs (21), Cendrillon (17), La Navarraise (4), Cléopâtre (3), Thérèse (2), Le Cid (2), Hérodiade (2), Esclarmonde (2), Chérubin (2) and Le mage (1).[80]

Other vocal music

Between 1862 and 1900 Massenet composed eight oratorios and cantatas, mostly on religious subjects.[81] There is a degree of overlap between his operatic style and his choral works for church or concert hall performance.[82] Vincent d'Indy wrote that there was "a discreet and semi-religious eroticism" in Massenet's music.[n 15] The religious element was a regular theme in his secular as well as sacred works: this derived not from any strong personal faith, but from his response to the dramatic aspects of Roman Catholic ritual.[42] The mingling of operatic and religious elements in his works was such that one of his oratorios, Marie-Magdeleine, was staged as an opera during the composer's lifetime.[73] Elements of the erotic and some implicit sympathy for sinners were controversial, and may have prevented his church works establishing themselves more securely.[17] Arthur Hervey, a contemporary critic not unsympathetic to Massenet, commented that Marie-Magdeleine and the later oratorio Ève (1875) were "the Bible doctored up in a manner suitable to the taste of impressionable Parisian ladies – utterly inadequate for the theme, at the same time very charming and effective."[84] Of the four works categorised by Irvine and Grove as oratorios, only one, La terre promise (1900), was written for church performance. Massenet used the term "oratorio" for that work, but he called Marie-Magdeleine a "drame sacré", Ève a "mystère", and La Vierge (1880) a "légende sacrée".[85]

Massenet composed many other smaller-scale choral works, and more than two hundred songs. His early collections of songs were particularly popular and helped establish his reputation. His choice of lyrics ranged widely. Most were verses by poets such as Musset, Maupassant, Hugo, Gautier and many lesser-known French writers, with occasional poems from overseas, including Tennyson in English and Shelley in French translation.[86] Grove comments that Massenet's songs, though pleasing and impeccable in craftsmanship, are less inventive than those of Bizet and less distinctive than those of Duparc and Fauré.[17]

Orchestral and chamber music

Massenet was a fluent and skilful orchestrator, and willingly provided ballet episodes for his operas, incidental music for plays, and a one-act stand-alone ballet for Vienna (Le carillon, 1892). Macdonald remarks that Massenet's orchestral style resembled that of Delibes, "with its graceful movement and bewitching colour", which was highly suited to classical French ballet.[17] The Méditation for solo violin and orchestra, from Thaïs, is possibly the best known non-vocal piece by Massenet, and appears on many recordings.[87] Another popular stand-alone orchestral piece from the operas is Le dernier sommeil de la Vierge from La Vierge, which has featured on numerous discs since the middle of the 20th century.[88]

A Parisian critic, after seeing La grand' tante, declared that Massenet was a symphonist rather than a theatre composer.[17] At the time of the British premiere of Manon in 1885, the critic in The Manchester Guardian, reviewing the work enthusiastically, nevertheless echoed his French confrère's view that the composer was really a symphonist, whose music was at its best when purely orchestral.[89] Massenet took a wholly opposite view of his talents. He was temperamentally unsuited to writing symphonically: the constraints of sonata form bored him. He wrote, in the early 1870s, "What I have to say, musically, I have to say rapidly, forcefully, concisely; my discourse is tight and nervous, and if I wanted to express myself otherwise I would not be myself."[90] His efforts in the concertante field made little mark, but his orchestral suites, colourful and picturesque according to Grove, have survived on the fringes of the repertoire.[17] Other works for orchestra are a symphonic poem, Visions (1891), an Ouverture de Concert (1863) and Ouverture de Phèdre (1873). After early attempts at chamber music as a student, he wrote little more in the genre. Most of his early chamber pieces are now lost; three pieces for cello and piano survive.[91]

Recordings

The only known recording made by Massenet is an excerpt from Sapho, "Pendant un an je fus ta femme", in which he plays a piano accompaniment for the soprano Georgette Leblanc. It was recorded in 1903, and was not intended for publication. It has been released on compact disc (2008), together with contemporary recordings by Grieg, Saint-Saëns, Debussy and others.[92]

In Massenet's later years, and in the decade after his death, many of his songs and opera extracts were recorded. Some of the performers were the original creators of the roles, such as Ernest van Dyck (Werther),[93] Emma Calvé (Sapho),[94] Hector Dufranne (Grisélidis),[95] and Vanni Marcoux (Panurge).[96] Complete French recordings of Manon and Werther, conducted by Élie Cohen, were issued in 1932 and 1933 and have been republished on CD.[97] The critic Alan Blyth comments that they embody the original, intimate Opéra-Comique style of performing Massenet.[97]

Of Massenet's operas, the two best known, Manon and Werther, have been recorded many times, and studio or live recordings have been issued of many of the others, including Cendrillon, Le Cid, Don Quichotte, Esclarmonde, Hérodiade, Le jongleur de Notre-Dame, Le mage, La Navarraise and Thaïs. Conductors on these discs include Sir Thomas Beecham, Richard Bonynge, Riccardo Chailly, Sir Colin Davis, Patrick Fournillier, Sir Charles Mackerras, Pierre Monteux, Sir Antonio Pappano and Michel Plasson. Among the sopranos and mezzos are Dame Janet Baker, Victoria de los Ángeles, Natalie Dessay, Renée Fleming, Angela Gheorghiu and Dame Joan Sutherland. Leading men in recordings of Massenet operas include Roberto Alagna, Gabriel Bacquier, Plácido Domingo, Thomas Hampson, Jonas Kaufmann, José van Dam, Alain Vanzo and Rolando Villazón.[98]

In addition to the operas, recordings have been issued of several orchestral works, including the ballet Le carillon, the piano concerto in E♭, the Fantaisie for cello and orchestra, and orchestral suites.[98] Many individual mélodies by Massenet were included in mixed recitals on record during the 20th century, and more have been committed to disc since then, including, for the first time, a CD in 2012, exclusively devoted to his songs for soprano and piano.[99]

Reputation

By the time of the composer's death in 1912 his reputation had declined, especially outside his native country. In the second edition (1907) of Grove, J A Fuller Maitland accused the composer of pandering to the fashionable Parisian taste of the moment, and disguising a uniformly "weak and sugary" style with superficial effects. Fuller Maitland contended that to discerning music lovers such as himself the operas of Massenet were "inexpressibly monotonous", and he predicted that they would all be forgotten after the composer's death.[100][n 16] Similar views were expressed in an obituary in The Musical Times:

His early scores are, for the greater part, his best ... Later, and for the plain reason that he never attempted to renovate his style, he sank into sheer mannerism. Indeed, one can but marvel that so gifted a musician, who lacked neither individuality nor skill, should have so utterly succeeded in throwing away his gifts. Success spoiled him ... the actual progress of musical art during the past forty years left Massenet unmoved ... he has taken no part in the evolution of modern music.[27]

Massenet was never entirely without supporters. In the 1930s Sir Thomas Beecham told the critic Neville Cardus, "I would give the whole of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos for Massenet's Manon, and would think I had vastly profited by the exchange."[102] By the 1950s critics were reappraising Massenet's works. In 1951 Martin Cooper of The Daily Telegraph wrote that Massenet's detractors, including some fellow composers, were on the whole idealistic, even puritanical, "but few of them have in practice achieved anything so near perfection in any genre, however humble, as Massenet achieved in his best works."[103] In 1955 Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor commented in The Record Guide that, although usually dismissed as an inferior Gounod, Massenet wrote music with a distinct flavour of its own. "He had a gift for melody of a suave, voluptuous and eminently singable kind, and the intelligence and dramatic sense to make the most of it." The writers called for revivals of Grisélidis, Le jongleur de Notre-Dame, Don Quichotte and Cendrillon, all then neglected.[45] By the 1990s, Massenet's reputation had been considerably rehabilitated. In The Penguin Opera Guide (1993), Hugh Macdonald wrote that though Massenet's operas never equalled the grandeur of Berlioz's Les Troyens, the genius of Bizet's Carmen or the profundity of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande, from the 1860s until the years before the First World War, the composer gave the French lyric stage a remarkable series of works, two of which – Manon and Werther – are "masterpieces that will always grace the repertoire". In Macdonald's view, Massenet "embodies many enduring aspects of the belle époque, one of the richest cultural periods in history".[42] In France, Massenet's 20th-century eclipse was less complete than elsewhere, but his oeuvre has been revalued in recent years. In 2003 Piotr Kaminsky wrote in Mille et un opéras of Massenet's skill in translating French text into flexible melodic phrases, his exceptional orchestral virtuosity, combining sparkle and clarity, and his unerring theatrical instinct.[104]

Rodney Milnes, in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (1992), agrees that Manon and Werther have a secure place in the international repertoire; he counts three others as "re-establishing a toehold" (Cendrillon, Thaïs and Don Quichotte), with many more due for re-evaluation or rediscovery. He concludes that comparing Massenet with the handful of composers of great genius, "It would be absurd to claim that he was anything more than a second-rate composer; he nevertheless deserves to be seen, like Richard Strauss, at least as a first-class second-rate one."[9]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- English pronunciations: UK: /ˈmæsəneɪ/, US: /ˌmæsəˈneɪ, mæsˈneɪ, mɑːsˈneɪ/.[1][2][3][4][5]

- Massenet's biographer Demar Irvine notes that, according to French usage of the time, the four children had the right to bear the more aristocratic surname Massenet de Marancour or Massenet Royer de Marancour. The elder brothers did so, but Jules preferred the plain single name.[7]

- Massenet was employed as accompanist to the leading tenor Gustave-Hippolyte Roger, at whose house at Villiers-sur-Marne Wagner spent ten days in early 1860. Massenet was impressed by Wagner's piano playing, "like a musician, not at all like a pianist". It is not clear whether Wagner heard Massenet play during his stay.[18]

- This was Massenet's second attempt at the Prix; he gained a mention honorable for his cantata Louise de Mézières in 1862.[20]

- A similar remark was made about Saint-Saëns in 1864: "Il sait tout, mais il manque d'inexpérience" – "He knows everything but lacks inexperience". Saint-Saëns, many years later, attributed it to Gounod.[22] It is more generally believed that the remark was made by Berlioz.[23]

- Massenet recalled in his memoirs that Hartmann's premises in the Boulevard de la Madeleine became an unofficial centre of Parisian musical life, with Bizet, Saint-Saëns, Lalo and Franck all "part of the inner circle".[28]

- Massenet succeeded François Bazin, a teacher whose pedantic methods had so repelled him when a student that he left Bazin's classes after a month.[35] Bazin is one of the few people about whom Massenet wrote a hard word in his memoirs.[36]

- Massenet's detractors put a different interpretation on his encouragement of his students' originality: Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi wrote in 1912, "He can hardly be said to have exercised a wholesome influence as a teacher, and generally speaking, such of his pupils as have displayed more than ordinary merits as composers did not follow his example."[27]

- Debussy's professor of composition was Ernest Guiraud.[39]

- According to Macdonald it was "the biblical-amorous subject" to which Vaucorbeil took exception – an objection that also applied to Saint-Saëns's Samson et Delila, which was banned from the Opéra for many years.[17] Massenet's recollection was that Vaucorbeil considered the librettist, Paul Milliet, incompetent.[40]

- This judgment was still shared by some well into the 20th century. The authors of The Record Guide (1955) observed that although Werther was popular in France it had never caught on elsewhere, "largely no doubt because of the monotonously self-pitying character of the hero (this is Goethe's fault rather than Massenet's)."[45]

- Irvine reiterates Massenet's claim, but cites no other authority for it.[61] The post was offered to and accepted by Fauré, whose biographers Duchen, Jones and Nectoux make no mention of any prior offer of the post to Massenet in 1905; nor is it mentioned in Woldu and Queuniet's 1996 study of the crisis that led to the handover from Dubois to Fauré.[62]

- These were Perséphone in Ariane, the title role in Thérèse, Queen Amahelli in Bacchus and Dulcinée in Don Quichotte. She appeared after the composer's death as Postumia in Roma and Colombe in Panurge.[65]

- "Une soirée bien parisienne et, naturellement, triomphe bien parisien aussi."[69]

- "Un érotisme discret et quasi-réligieux"[83]

- Fuller Maitland was equally antipathetic to many contemporary composers, being similarly hostile to Sullivan, Elgar, Debussy and Richard Strauss.[101]

References

- Wells 2008.

- Jones 2011.

- "Massenet". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- "Massenet". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- "Massenet". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Jules Massenet at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Irvine, p. 1

- Irvine, p. 2

- Milnes, Rodney. "Massenet, Jules" The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 28 July 2014 (subscription required)

- Massenet, pp. 5 and 7

- Irvine, p. 9

- Massenet, p. 8 and Irvine, p. 9

- Irvine, p. 11

- Massenet, p. 16; Finck, p. 24; and Irvine, p. 12

- Massenet, p. 18

- Irvine, p. 15

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Massenet, Jules", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 20 July 2014 (subscription required)

- Irvine, pp. 21–22

- Irvine, p. 24

- Irvine, p. 25

- Massenet, pp. 27–28

- Bellaigue, p. 59; and Studd, p. 57

- Gallois, p. 96; and Harding, p. 90

- Irvine, pp. 31–32

- Massenet p. 50

- Massenet, p. 63

- Calvocoressi, M-D. "Jules Massenet", The Musical Times, September 1912, pp. 565–566 (subscription required)

- Massenet, p. 81

- Massenet, p. 73

- Irvine, p. 58

- Massenet, pp. 94–95

- Milnes, Rodney. "Roi de Lahore, Le", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 13 May 2019 (subscription required)

- Finck, pp. 185 and 189

- "Il re di Lahore", The Times, 30 June 1879, p. 13

- Irvine, p. 20

- Massenet, p. 65

- Smith, p. 119

- Koechlin, p. 8

- Lesure, François and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 28 July 2014 (subscription required)

- Massenet, p. 126

- Milnes, Rodney. "Hérodiade", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 29 July 2014 (subscription required)

- Macdonald, pp. 216–217

- Massenet's New Success – The Production of his Cid and its Great Merits", The New York Times, 20 December 1885

- Milnes, Rodney. "Werther", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 29 July 2014 (subscription required)

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 433

- Rowden, Clair. "Caricature and the Unconscious: Jules Massenet's Thaïs, a Case Study" Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography, 34/1-2 (2009), pp. 274–289 (subscription required)

- Balthazar, p. 213; Riding and Dunton-Downer, p. 264; and Smillie, Thomson. Opera Explained – Werther, Naxos, retrieved 29 July 2014

- "The Sorrows of Werther", The New York Times, 20 April 1894

- Irvine, pp. 190–192

- Irvine, pp. 193–194

- "Royal Opera", The Times, 21 June 1894, p. 10

- "Paris", The Times, 7 May 1896, p. 5

- "France", The Times, 8 May 1896, p. 5; and Nichols, p. 23

- Massenet, p. 216; and Irvine, p. 204

- Duchen, p. 122; Gordon, p. 131; Johnson, p. 260; Jones, p. 78; Nectoux (1994), p. 63; and Smith, p. 137

- Nectoux (1991), p. 227

- Irvine, p. 209

- Finck, p. 117

- Irvine, pp. 219–223

- Massenet, p. 216

- Irvine, p. 206

- Woldu, Gail Hilson and Sophie Queuniet. "Au-delà du scandale de 1905: Propos sur le Prix de Rome au début du XXe siècle", Revue de Musicologie, T. 82, No 2 (1996), pp. 245–267 (in French) (subscription required)

- Crichton, Ronald. "Massenet and after", The Musical Times, February 1971, p. 132 (subscription required)

- Maddock, Fiona. "Tristan und Isolde at the ROH, Werther at Opera North", The Observer, 4 October 2009, p. C17

- Forbes, Elizabeth. "Arbell, Lucy", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 8 August 2014 (subscription required)

- Finck, p. 209

- Irvine, p. 257

- Irvine, pp. 264–266

- Finck, p. 222

- "Death of M. Jules Massenet", The Times, 14 August 1912, p. 7

- Irvine, pp. 296–298

- Shaw, p. 244

- "Jules-Émile-Frédéric Massenet", OperaGlass, retrieved 5 August 2014

- Quoted in The New Yorker, Volume 61, Issues 46–52, p. 96

- Porter, Andrew. "Tilting in the approved manner", The Observer, 16 October 1994, p. C18

- Irvine, pp. 319–320

- Shaw, pp. 245–246

- Massenet, Le mage, opera in 5 acts", Allmusic, retrieved 2 August 2014

- "Composers", Operabase, retrieved 2 August 2014

- "Opera statistics 2012/13 – Massenet", Operabase, retrieved 2 August 2014

- Irvine, pp. 326–327

- Irvine, p. 116

- Gut, p. 90

- Hervey, pp. 179–180

- Irvine, pp. 325–326

- Irvine, pp. 229–333

- "Massenet: Méditation, Thaïs", WorldCat, retrieved 10 August 2014

- "Dernier sommeil de la Vierge", WorldCat, retrieved 10 August 2014

- "Manon Lescaut", The Manchester Guardian, 8 May 1885, p. 8

- Irvine, p. 61

- Finck, p. 233

- "Legendary Piano Recordings – Track listing" Archived 6 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Marston Records; and " Legendary piano recordings : the complete Grieg, Saint-Saëns, Pugno, and Diémer and other G & T rarities" WorldCat; both retrieved 21 July 2014

- Blyth (1979), p. 500

- "Emma Calvé : the complete 1902 G&T, 1920 Pathé and Mapleson cylinder recordings", WorldCat, retrieved 11 August 2014

- Kelly, p. 123

- Kelly, p. 173

- Blyth (1994), pp. 105–106

- March, pp. 734–738; and "Massenet", WorldCat, retrieved 31 July 2014; and , retrieved 27 December 2017

- "Ivre d'amour", WorldCat, retrieved 7 August 2012

- Fuller Maitland, p. 88

- Dibble, Jeremy. "Fuller Maitland, J A" Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, retrieved 29 July 2014 (subscription required); and McHale, Maria. "The English Musical Renaissance and the Press 1850–1914: Watchmen of Music by Meirion Hughes", Music and Letters (2003) Vol 84 (3), pp. 507–509 (subscription required)

- Cardus, p. 29

- Cooper, French Music (1951), quoted in Hughes and van Thal, p. 250

- Kaminsky, p. 864

Sources

- Balthazar, Scott (2013). Historical Dictionary of Opera. Lanham, US: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810867680.

- Bellaigue, Camille (1921). Souvenirs de musique et de musiciens (in French). Paris: Nouvelle Librairie Nationale. OCLC 15309469.

- Blyth, Alan (1979). Opera on Record Volume 1. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 874515332.

- Blyth, Alan (1994) [1992]. Opera on CD. London: Kyle Cathie. ISBN 1856261034.

- Cardus, Neville (1961). Sir Thomas Beecham. London: Collins. OCLC 1290533.

- Duchen, Jessica (2000). Gabriel Fauré. London: Phaidon. ISBN 0714839329.

- Finck, Henry (1910). Massenet and His Operas. New York and London: John Lane. OCLC 3424135.

- Fuller Maitland, J A, ed. (1916) [1907]. Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 3 (second ed.). Philadelphia: Theodore Presser. OCLC 317326125.

- Gallois, Jean (2004). Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (in French). Brussels: Éditions Mardaga. ISBN 2870098510.

- Gordon, Tom (2013). Regarding Fauré. London: Routledge. ISBN 130622196X.

- Gut, Serge (1984). Le groupe Jeune France (in French). Paris: Champion. OCLC 13515287.

- Harding, James (1965). Saint-Saëns and His Circle. London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 60222627.

- Hervey, Arthur (1894). Masters of French Music. London: Osgood, McIlvaine. OCLC 6551952.

- Hughes, Gervase; Herbert van Thal, eds. (1971). The Music Lover's Companion. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. ISBN 0413279200.

- Irvine, Demar (1994). Massenet – A Chronicle of His Life and Times. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 1574670247.

- Johnson, Graham (2009). Gabriel Fauré – The Songs and their Poets. Farnham, UK; Burlington, US: Ashgate. ISBN 0754659607.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, J Barrie (1989). Gabriel Fauré – A Life in Letters. London: B T Batsford. ISBN 0713454687.

- Kaminski, Piotr (2003). Mille et un opéras (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2213600171.

- Kelly, Alan (1990). La Voix de son maître – His Master's Voice: the French catalogue, 1898–1929. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313273332.

- Koechlin, Charles (1976) [1945]. Gabriel Fauré, 1845–1924. London: Dennis Dobson. ISBN 0404146791.

- Macdonald, Hugh (1997) [1993]. "Massenet, Jules". In Amanda Holden (ed.). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 014051385X.

- March, Ivan, ed. (2008). Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, 2009. London and New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0141041625.

- Massenet, Jules; H Villiers Barnett (trans) (1919) [1910]. My Recollections. Boston: Small Maynard. OCLC 774419363.

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel; Roger Nichols (trans) (1991). Gabriel Fauré – A Musical Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521235243.

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1994). Camille Saint-Saëns et Gabriel Fauré – Correspondance, 1862–1920 (in French). Paris: Société française de musicologie. ISBN 2853570045.

- Nichols, Roger (2011). Ravel – A Life. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300108826.

- Riding, Alan; Leslie Dunton-Downer (2006). Opera. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 1405312793.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Desmond Shawe-Taylor (1955). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Shaw, Bernard (1981). Dan Laurence (ed.). Shaw's Music: The Complete Music Criticism of Bernard Shaw, Volume 1 (1876–1890). London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 0370302478.

- Smith, Rollin (2010). Saint-Saëns and the Organ. Stuyvesant, US: Pendragon. ISBN 1576471802.

- Studd, Stephen (1999). Saint-Saëns – A Critical Biography. London: Cygnus Arts. ISBN 1900541653.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Harlow, Essex: Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Massenet, Anne; Mary Dibbern (trans) (2015) [2001]. Massenet and His Letters. Hillsdale, US: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1576472086.

- Fuller, Nick (22 August 2016). "Jules Massenet: His Life and Works" (PDF). MusicWeb International. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jules Massenet. |

- Jules Massenet at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Official website (Association Massenet Internationale), International Massenet Association, founded in 1990

- All Music biographical notes on Massenet (in English)

- Extensive biography with list of references and compositions (in French)

- Rudolf Lehmann's drawing of Massenet in the British Museum, 1893

- Works by Jules Massenet at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jules Massenet at Internet Archive

- "Massenet, Mary Garden, and the Chicago Opera 1910–1932" (Includes charts, cast lists, programs, and many photos)

- Scores and Vocal Scores