Mass racial violence in the United States

Mass racial violence in the United States, also called race riots, can include such disparate events as:

- Racially based communal conflict against African Americans that took place before the American Civil War, often in relation to attempted slave revolts, and after the war, in relation to tensions under Reconstruction and later efforts to suppress black voting and institute Jim Crow

- Conflict between Americans and recent European immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries

- Between Asian Americans and White Americans during and after the Gold Rush, culminating in the Chinese massacre of 1871 as well as the Rock Springs massacre

- Attacks on Native Americans and Americans over the land (see also: California Genocide, List of Indian massacres)

- Frequent fighting among various ethnic groups in major cities, specifically in the Northeast and Midwest United States throughout the late 19th century and early 20th century, as fictionalized in the 1957 stage musical West Side Story and its 1961 film adaptation, depicting ethnic conflict in New York between Puerto Ricans and Italians

- Anti-immigrant violence targeted at Latin Americans in the 20th century

- Two concurrent but distinct patterns of disturbances in the civil rights era: racial disturbances resulting from demonstrations and protests, as at the Marquette Park Illinois march of August 1966 or at the 1969 Greensboro uprising in North Carolina, as opposed to the Ghetto riots in the United States (1964–1969), a grouping that includes the Long, hot summer of 1967 and the King assassination riots of 1968, which caused mass violence, looting, and long-lasting damage within African-American communities.

History

Genocide of the California Indigenous Natives

In the latter half of the 19th century California state and Federal authorities, incited[4][5] aided and financed miners, settlers, ranchers and people's militias to enslave, kidnap, murder, and exterminate a major proportion of displaced Native American Indians. The latter were sometimes contemptuously referred to as "Diggers", for their practice of digging up roots to eat. Many of the same policies of violence were used here against the indigenous population as the United States had done throughout its territory.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12] California statehood, private militias, Federal reservations, and sections of the US Army all participated in a deliberate campaign to wipe out California Indians with the state and federal governments paying millions of dollar to militias who hunted and murdered Indians,[1][2] Federal Reservations deliberately starving Indians to death by reducing caloric distribution to them from 480–910 to 160–390[1] and the U.S. Army killed 1,680 to 3,741 California Indians themselves. California governor Peter Burnett even predicted: "That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct, must be expected. While we cannot anticipate the result with but painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power and wisdom of man to avert."[13][14] Between 1850 and 1852 the state appropriated almost one million dollars for the activities of these militias, and between 1854 and 1859 the state appropriated another $500,000, almost half of which was reimbursed by the federal government.[15] Numerous books have been written on the subject of the California Indian genocide such as Genocide and Vendetta: The Round Valley Wars in Northern California by Lynwood Carranco and Estle Beard, Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846–1873 by Brendan C. Lindsay, and An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 by Benjamin Madley among others. That last book by Madley caused California governor Jerry Brown to recognize the genocide.[2] Even Guenter Lewy famous for the phrase: "In the end, the sad fate of America's Indians represents not a crime but a tragedy, involving an irreconcilable collision of cultures and values" concedes that what happened in California may constitute genocide: "some of the massacres in California, where both the perpetrators and their supporters openly acknowledged a desire to destroy the Indians as an ethnic entity, might indeed be regarded under the terms of the convention as exhibiting genocidal intent."[3] In a speech before representatives of Native American peoples in June, 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom apologized for the genocide. Newsom said, "That's what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that's the way it needs to be described in the history books."[16]

By one estimate, at least 4,500 California Indians were killed between 1849 and 1870.[17] Contemporary historian Benjamin Madley has documented the numbers of California Indians killed between 1846 and 1873; he estimates that during this period at least 9,400 to 16,000 California Indians were killed by non-Indians. Most of the deaths took place in what he defined as more than 370 massacres (defined as the "intentional killing of five or more disarmed combatants or largely unarmed noncombatants, including women, children, and prisoners, whether in the context of a battle or otherwise").[18] Professor Ed Castillo, of Sonoma State University, estimates that more were killed: "The handiwork of these well armed death squads combined with the widespread random killing of Indians by individual miners resulted in the death of 100,000 Indians in the first two years of the gold rush."[19]

Anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic violence

Riots defined by "race" have taken place between ethnic groups in the United States since at least the 18th century and they may have also occurred before it. During the early-to-mid- 19th centuries, violent rioting occurred between Protestant "Nativists" and recently arrived Irish Catholic immigrants.

The San Francisco Vigilance Movements of 1851 and 1856 have been described as responses to rampant crime and government corruption. But, since the late 20th century, historians have noted that the vigilantes had a nativist bias; they systematically attacked Irish immigrants, and later they attacked Mexicans and Chileans who came as miners during the California Gold Rush, and Chinese immigrants. During the early 20th century, racial or ethnic violence was directed by whites against Filipinos, Japanese and Armenians in California, who had arrived in waves of immigration.[20]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italian immigrants were subject to racial violence. In 1891, eleven Italians were lynched by a mob of thousands in New Orleans.[21] In the 1890s a total of twenty Italians were lynched in the South.

The Reconstruction era (1863–1877)

Immediately following the Civil War, political pressure from the North called for a full abolition of slavery. The South's lack of voting power led to the passing of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, which in theory gave African-American and other minority males equality and voting rights, along with abolishing slavery. Although the federal government originally kept troops in the South to protect these new freedoms, this time of progress was cut short.[22]

By 1877 the North had lost its political will in the South and while slavery remained abolished, the Black Codes and segregation laws helped erase most of the freedoms passed by the 14th and 15th amendments. Through violent economic tactics and legal technicalities, African-Americans were forced into sharecropping and were gradually removed from the voting process.[22]

The lynching era (1878–1939)

Lynching, defined as "the killing of an individual or small group of individuals by a 'mob' of people" was a particular form of ritualistic murder, often involving the majority of the local white community. Lynching was sometimes announced in advance and became a spectacle for an audience to witness. Lynchings in the United States dropped in number from the 1880s to the 1920s, but there were still an average of about 30 lynchings per year during the 1920s. A study done of 100 lynchings from 1929 to 1940 discovered that at least one third of the victims were innocent of the crimes they were accused of.[23]

Racial and ethnic cleansing took place on a large scale in this time period, particularly towards Native Americans, who were forced off their land and relocated to reservations. Along with Native Americans, Chinese Americans in the Pacific Northwest and African Americans throughout the United States were rounded up and expunged from towns under threat of mob rule, often intending to harm their targets.[23]

The civil rights era (1940–1971)

Though the Roosevelt administration, under tremendous pressure, engaged in anti-racist propaganda and in some cases helped push for African-American employment, African Americans were still experiencing immense violence, particularly in the South. In March 1956, United States Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina created the Southern Manifesto,[24] which promised to fight to keep Jim Crow alive by all legal means.[25]

This continuation of support for Jim Crow and segregation laws led to protests in which many African-Americans were violently injured out in the open at lunchroom counters, buses, polling places and local public areas. These protests did not eviscerate racism, but it forced racism to become used in more coded or metaphorical language instead of being used out in the open.[25]

The modern era (1972–present)

Today racial violence has changed dramatically, as open violent acts of racism are rare, but acts of police brutality and the mass incarceration of racial minorities continues to be a major issue facing the United States. The War on Drugs[26] has been noted as a direct cause for the dramatic increase in incarceration, which has risen from 300,000 to more than 2,000,000 from 1980 to 2000 in the nation's prison system, though it does not account for the disproportionate African American homicide and crime rate, which peaked before the War on Drugs began.[27]

Nineteenth-century events

Like lynchings, race riots often had their roots in economic tensions or in white defense of the color line. In 1887, for example, ten thousand workers at sugar plantations in Louisiana, organized by the Knights of Labor, went on strike for an increase in their pay to $1.25 a day. Most of the workers were black, but some were white, infuriating Governor Samuel Douglas McEnery, who declared that "God Almighty has himself drawn the color line." The militia was called in, but withdrawn to give free rein to a lynch mob in Thibodaux. The mob killed between 20 and 300 blacks. A black newspaper described the scene:

'Six killed and five wounded' is what the daily papers here say, but from an eye witness to the whole transaction we learn that no less than thirty-five Negroes were killed outright. Lame men and blind women shot; children and hoary-headed grandsires ruthlessly swept down! The Negroes offered no resistance; they could not, as the killing was unexpected. Those of them not killed took to the woods, a majority of them finding refuge in this city.[28]

In 1891, a mob lynched Joe Coe, a black worker in Omaha, Nebraska suspected of attacking a young white woman from South Omaha. Approximately 10,000 white people, mostly ethnic immigrants from South Omaha, reportedly swarmed the courthouse, setting it on fire. They took Coe from his jail cell, beating and then lynching him. Reportedly 6,000 people visited Coe's corpse during a public exhibition, at which pieces of the lynching rope were sold as souvenirs. This was a period when even officially sanctioned executions, such as hangings, were regularly conducted in public.[29]

Twentieth-century events

Labor and immigrant conflict was a source of tensions that catalyzed as the East St. Louis riot of 1917. White rioters, many of them ethnic immigrants, killed an estimated 100 black residents of East St. Louis, after black residents had killed two white policemen, mistaking the car they were riding in for a previous car of white occupants who drove through a black neighborhood and fired randomly into a crowd of black people .

White-on-Black race riots include the Atlanta riots (1906), the Omaha and Chicago riots (1919), part of a series of riots in the volatile post-World War I environment, and the Tulsa massacre (1921).

The Chicago race riot of 1919 grew out of tensions on the Southside, where Irish descendants and African Americans competed for jobs at the stockyards, and where both were crowded into substandard housing. The Irish descendants had been in the city longer, and were organized around athletic and political clubs.

A young black Chicagoan, Eugene Williams, paddled a raft near a Southside Lake Michigan beach into "white territory", and drowned after being hit by a rock thrown by a young white man. Witnesses pointed out the killer to a policeman, who refused to make an arrest. An indignant black mob attacked the officer.[30] Violence broke out across the city. White mobs, many of them organized around Irish athletic clubs, began pulling black people off trolley cars, attacking black businesses, and beating victims. Having learned from the East St. Louis riot, the city closed down the street car system, but the rioting continued. A total of 23 black people and 15 white people were killed.[31]

The 1921 Tulsa race massacre was the result of economic competition, and white resentment of black successes in Greenwood, which was compared to Wall Street and filled with independent businesses. In the immediate event, black people resisted white people who tried to lynch 19-year-old Dick Rowland, who worked at shoeshines. Thirty-nine people (26 black, 13 white) were confirmed killed. An early 21st century investigation of these events has suggested that the number of casualties could be much higher. White mobs set fire to the black Greenwood district, destroying 1,256 homes and as many as 200 businesses. Fires leveled 35 blocks of residential and commercial neighborhood. Black people were rounded up by the Oklahoma National Guard and put into several internment centers, including a baseball stadium. White rioters in airplanes shot at black refugees and dropped improvised kerosene bombs and dynamite on them.[32]

By the 1960s, decades of racial, economic, and political forces, which generated inner city poverty, resulted in race riots within minority areas in cities across the United States. The beating and rumored death of cab driver John Smith by police, sparked the 1967 Newark riots. This event became, per capita, one of the deadliest civil disturbances of the 1960s. The long and short term causes of the Newark riots are explored in depth in the documentary film Revolution '67 and many news reports of the times. The riots in Newark spread across the United States in most major cities and over 100 deaths were reported. Many inner city neighborhoods in these cities were destroyed. The assassinations of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee and later of Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles in 1968 also led to nationwide rioting across the country with similar mass deaths. During the same time period, and since then, violent acts committed against African-American churches and their members have been commonplace.

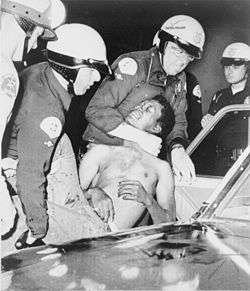

During the 1980s and '90s a number of riots occurred that were related to longstanding racial tensions between police and minority communities. The 1980 Miami riots were catalyzed by the killing of an African-American motorist by four white Miami-Dade Police officers. They were subsequently acquitted on charges of manslaughter and evidence tampering. Similarly, the six-day 1992 Los Angeles riots erupted after the acquittal of four white LAPD officers who had been filmed beating Rodney King, an African-American motorist. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, the Director of the Harlem-based Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has identified more than 100 instances of mass racial violence in the United States since 1935 and has noted that almost every instance was precipitated by a police incident.[33]

Twenty-first-century events

The Cincinnati riots of 2001 were caused by the killing of 19-year-old African-American Timothy Thomas by white police officer Stephen Roach, who was subsequently acquitted on charges of negligent homicide.[34] The 2014 Ferguson unrest occurred against a backdrop of racial tension between police and the black community of Ferguson, Missouri in the wake of the police shooting of Michael Brown; similar incidents elsewhere such as the shooting of Trayvon Martin sparked smaller and isolated protests. According to the Associated Press' annual poll of United States news directors and editors, the top news story of 2014 was police killings of unarmed black people, including Brown, as well as the investigations and the protests afterward.[35][36] During the 2017 Unite the Right Rally, an attendee drove his car into a crowd of people protesting the rally, killing 32-year-old Heather D. Heyer and injuring 19 others, and was indicted on federal hate crime charges.[37]

Timeline of events

Nativist period 1700s–1860

- For information about riots worldwide, see List of riots.

- 1763: Pontiac's War

- 1811: German Coast Uprising (Louisiana)

- 1829: Cincinnati riots of 1829 (Cincinnati, Ohio). Rioting against African Americans results in thousands leaving for Canada.

- 1829: Charlestown anti-Catholic riots (Charlestown, Massachusetts)

- 1831: Nat Turner's slave rebellion (Southampton County, Virginia)

- 1834: Ursuline Convent riots (Charlestown, Massachusetts, near Boston)

- 1834: New York anti-abolitionist riots (1834)

- 1835: Snow Riot (Washington, D.C.)

- 1835: Five Points Riot (New York City)

- 1836: Cincinnati riots of 1836 (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- 1841: Cincinnati riots of 1841 (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- 1844: Philadelphia Nativist Riots (May 6–8/July 5–8)

- 1851: Hoboken anti-German riot

- 1855: Bloody Monday (Louisville, Kentucky, anti-German riots)

Civil War period 1861–1865

- 1863: Detroit race riot

- 1863: New York City draft riots, Irish against blacks

Post–Civil War and Reconstruction period: 1865–1877

- 1866: New Orleans massacre of 1866 (New Orleans, Louisiana)

- 1866: Memphis riots of 1866 (Memphis, Tennessee), mostly ethnic Irish against African Americans

- 1868: Pulaski riot (Pulaski, Tennessee), whites against blacks

- 1868: St. Bernard Parish massacre, St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, whites against blacks

- 1868: Opelousas massacre (Opelousas, Louisiana), whites against blacks

- 1868: Camilla race riot (Camilla, Georgia), whites against blacks

- 1868: Ward Island riot

- Irish and German-American indigent immigrants, temporarily interned at Wards Island by the Commissioners of Emigration, begin rioting following an altercation between two residents, resulting in thirty men seriously wounded and around sixty arrested.[38]

- 1870: Eutaw massacre, whites against blacks

- 1870: Laurens, South Carolina

- 1870: Kirk-Holden war: Alamance County, North Carolina

- Federal troops, led by Col. Kirk and requested by NC governor Holden, were sent to extinguish racial violence. Holden was eventually impeached because of the offensive.

- 1870: New York City orange riot

- 1871: Meridian race riot of 1871, Meridian, Mississippi, whites against blacks

- 1871: Second New York City orange riot

- 1871: Los Angeles anti-Chinese riot, mixed Mexican and white mob killed 17–20 Chinese in the largest mass lynching in U.S. history

- 1871: Scranton coal riot

- Violence occurs between striking members of a miners' union in Scranton, Pennsylvania when Welsh miners attack Irish and German-American miners who chose to leave the union and accept the terms offered by local mining companies.[39]

- 1873: Colfax, Louisiana, white Democrats against black Republicans

- 1874: Vicksburg, Mississippi

- 1874: Battle of Liberty Place, New Orleans, Louisiana[40] After contested gubernatorial election, Democrats took over state buildings for three days

- 1874: Coushatta massacre, Coushatta, Louisiana, white Democrats against black Republicans

- 1875: Yazoo City, Mississippi

- 1875: Clinton, Mississippi

- 1876: Statewide violence in South Carolina

- 1876: Hamburg massacre, Hamburg, South Carolina

- 1876: Ellenton riot, Ellenton, South Carolina

Jim Crow period: 1877–1914

- 1885: Rock Springs, Wyoming

- 1885: Tacoma, Washington

- 1886: Pittsburgh riot

- 1886: Seattle, Washington

- 1887: Denver riot of 1887

- 1887: Hells Canyon Massacre

- In one of the largest civil disturbances in the city's history, fighting between Swedish, Hungarian and Polish immigrants resulted in the shooting death of one man and several others were injured before it was broken up by police.[41]

- 1887: Thibodaux massacre, Thibodaux, Louisiana—strike of 10,000 sugar-cane workers was opposed by whites, who rioted and killed an estimated 50 African Americans

- 1891: New Orleans anti-Italian riot

- A lynch mob storms a local jail and hangs 11 Italians following the acquittal of several Sicilian immigrants alleged to be involved in the murder of New Orleans police chief David Hennessy.

- 1891: 1st Omaha race riot

- 10,000 white people storm the local courthouse to beat and lynch Joe Coe, alleged to have raped a white girl.

- 1894: Buffalo, New York riot of 1894

- Two groups of Irish and Italian-Americans are arrested by police after fighting following a barroom brawl. After the mob is dispersed by police, five Italians are arrested while two others are sent to a local hospital.[42]

- Much of the violence in this national strike was not specifically racial. In Iowa, where employees of Consolidation Coal Company (Iowa) refused to join the strike, armed confrontation between strikers and strike breakers took on racial overtones because the majority of Consolidation's employees were African American. The National Guard was mobilized to avert open warfare.[43][44][45]

- 1895: 1895 New Orleans dockworkers riot

- 1898: Wilmington race riot

- A group of Democrats sought to remove African-Americans from the political scene, and went about this by launching a campaign of accusing African-American men of sexually assaulting white women. About five hundred white men attacked and burned Alex Manly's office, a newspaper editor who suggested African-American men and white women had consensual relationships. Fourteen African-Americans were killed.[46]

- 1898: Lake City, South Carolina

- 1898: Greenwood County, South Carolina

- 1899: Newburg, New York riot

- Angered about hiring of African-American workers, a group of 80-100 Arab laborers attack African Americans near the Freeman & Hammond brick yard, with numerous men injured on both sides.[47]

- 1900: New Orleans, Louisiana: Robert Charles riots

- 1900: New York City

- 1902: New York City

- Anti-Semitic riots initiated by German factory workers and city policemen against thousands of Jews attending Jacob Joseph's funeral

- 1906: Little Rock, Arkansas

- Started after a white police officer in Argenta (North Little Rock) killed a black musician, and another black was killed; racial tensions rose with exchange of gunfire, resulting in half a block of buildings burned down; whites rioted and some blacks fled the city.[48]

- 1906: Atlanta riots, Georgia

- In September after two newspapers printed stories about African-American men assaulting white women anti-African-American violence broke out. Roughly 10,000 white men and boys took the street, resulting in the deaths of 25 to 100 African-Americans, along with hundreds injured.[46]

- 1906: Wahalak & Scooba, Mississippi[49]

- 1907: Bellingham riots, Washington

- 1908: Springfield, Illinois

- 1909: Greek Town riot

- A successful Greek immigrant community in South Omaha, Nebraska is burnt to the ground by ethnic whites and its residents are forced to leave town.[50]

- 1910: Nationwide riots following the heavyweight championship fight between Jack Johnson and Jim Jeffries in Reno, Nevada on July 4

- 1910 Slocum massacre, between eight and two hundred black residents around Slocum, Texas were killed by hundreds of armed white men. Eleven white men were arrested, none went to trial.[51]

War and Inter-War period: 1914–1945

- 1917: East St. Louis, Illinois

- On July 1st, an African-American man was rumored to have killed a white man. Violence against African-American continued for a week, resulting in estimations of 40 to 200 dead African-Americans. In addition, almost 6,000 African-Americans lost their homes during the riots then fled East St. Louis.[46]

- 1917: Chester, Pennsylvania. The 1917 Chester race riot took place over four days in July. White hostility toward southern blacks moving to Chester for wartime economy jobs erupted into a four day melee sparked by the stabbing of a white man by a black man. Mobs of hundreds of people fought throughout the city and the violence resulted in 7 deaths, 28 gunshot wounds, 360 arrests and hundreds of hospitalizations.[52]

- 1917: Lexington, Kentucky. Tensions already existed between black and white populations over the lack of affordable housing in the city during the Great Migration. On the day of the riot, September 1, the Colored A.&M. Fair (one of the largest African American fairs in the South) on Georgetown Pike attracted more African Americans from the surrounding area into the city. Also during this time, some National Guard troops were camping on the edge of the city. Three troops passed in front of an African American restaurant and shoved some people on the sidewalk. A fight broke out, reinforcements for the troops and citizens both appeared, and soon a riot had begun. The Kentucky National Guard was summoned, and once the riot had ended, armed soldiers on foot and mount and police patrolled the streets. All other National Guard troops were barred from the city streets until the fair ended.[53]

- 1917: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 1917: Houston, Texas

- Red Summer of 1919. Tension in the summer of 1919 stemmed significantly from white soldiers returning from World War I and finding that their jobs had been taken by African-American veterans.[46]

- 1919: Elaine Race Riot (Elaine, Arkansas)

- 1919: Washington race riot of 1919

- 1919: Jenkins County, Georgia, riot of 1919

- 1919: Macon, Mississippi, race riot

- 1919: Chicago Race Riot of 1919

- 1919: Baltimore riot of 1919

- 1919: Omaha Race Riot of 1919

- 1919: Charleston riot of 1919

- 1919: Longview, Texas

- 1919: Knoxville Riot of 1919 (Knoxville, Tennessee)

- 1920: Ocoee Massacre (Ocoee, Florida)

- 1920: West Frankfort, Illinois

- 1921: Tulsa race massacre (Tulsa, Oklahoma)

- Between May 31st and June 1st, a young white woman accused an African American man of grabbing her arm in an elevator. The man Dick Rowland was arrested and police launched an investigation. A mob of armed white men gathered outside the Tulsa County Courthouse, where gunfire ensued. During the violence, 1,250 homes were destroyed and roughly 6,000 African-Americans were imprisoned after the Oklahoma National Guard was called in. The state of Oklahoma reports that twenty-six African-Americans died along with 10 whites.

- 1923: Rosewood Massacre (Rosewood, Florida)

- 1927: Little Rock, Arkansas

- Lynching of John Carter, a suspect in a murder, was followed by rioting by 5,000 whites in the city, who destroyed a black business area[54]

- A wave of civil unrest, violence, and vandalism by local White mobs against Blacks, as well Greek, Jewish, Chinese and Puerto Rican targets in the community.

- 1930: Watsonville, California

- 1935: Harlem, Manhattan, New York

- 1943: Detroit, Michigan

- In late June a fistfight broke out between an African-American man and a white man at an amusement park on Belle Isle. The violence escalated from there and led to three days of intense fighting, in which 6,000 United States Army troops were brought in. This resulted in twenty-five African-Americans dying, along with nine white deaths and a total of seven hundred injured persons.[46]

- 1943: Harlem, Manhattan, New York

- 1943: Los Angeles, California

- 1944: Guam

Civil rights movement: 1955–1973

1963

1964

- Chester school protests; Chester, Pennsylvania - April

- Rochester 1964 race riot; Rochester, New York – July

- New York City 1964 riot; New York City – July

- Philadelphia 1964 race riot; Philadelphia – August

- Jersey City 1964 race riot, August 2–4, Jersey City, New Jersey

- Paterson 1964 race riot, August 11–13, Paterson, New Jersey

- Elizabeth 1964 race riot, August 11–13, Elizabeth, New Jersey

- Chicago 1964 race riot, Dixmoor race riot, August 16–17, Chicago

1965

- Watts riots; Los Angeles, California – August

- This predominately African-American neighborhood exploded with violence from August 11th to August 17th after the arrest of 21-year old Marquette Frye, a black motorist who was arrested by a white highway patrolman. During his arrest a crowd had gathered and a fight broke out between the crowd and the police, escalating to the point in which rocks and concrete were thrown at police. 30,000 people were recorded participating in the riots and fights with police, which left thirty four people dead, 1,000 injured and 4,000 arrested.

1966

- Hough riots; Cleveland, Ohio – July

- Division Street riots; Chicago, Illinois – June

- Marquette Park riot; Chicago, Illinois – August

- Hunters Point riot; San Francisco – September

1967

- 1967 Newark riots; Newark, New Jersey – July

- 1967 Plainfield riots; Plainfield, New Jersey – July

- 12th Street riot; Detroit, Michigan – July

- 1967 New York City riot; Harlem, New York City – July

- Cambridge riot of 1967; Cambridge, Maryland – July

- 1967 Rochester riot; Rochester, New York – July

- 1967 Pontiac riot; Pontiac, Michigan – July

- 1967 Toledo riot; Toledo, Ohio – July

- 1967 Flint riot; Flint, Michigan – July

- 1967 Grand Rapids riot; Grand Rapids, Michigan – July

- 1967 Houston riot; Houston, Texas – July

- 1967 Englewood riot; Englewood, New Jersey – July

- 1967 Tucson riot; Tucson, Arizona – July

- 1967 Milwaukee riot; Milwaukee, Wisconsin – July

- Minneapolis North Side riots; Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota – August

- 1967 Albina Riot Portland, Oregon – August 30[55]

1968

- Orangeburg massacre; Orangeburg, South Carolina – February

- King assassination riots: 125 cities in April and May, in response to the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. including:

- Baltimore riot of 1968; Baltimore Maryland

- 1968 Washington, D.C. riots; Washington, D.C.

- 1968 New York City riot; New York City

- West Side Riots; Chicago

- 1968 Detroit riot; Detroit, Michigan

- Louisville riots of 1968; Louisville, Kentucky

- Hill District MLK riots; Pittsburgh, PA

- Summit, Illinois, race riot at Argo High School, September 1968

- 1968 Miami riot

- 1968 Democratic National Convention

1969

- 1969 York race riot; York, Pennsylvania – July

- 1969 Hartford Riots, September 1–4, Hartford, Connecticut

1970

- Augusta riot; Augusta, Georgia – May

- Jackson State killings; Jackson, Mississippi – May

- Asbury Park riots; Asbury Park, New Jersey – July

- Chicano Moratorium, an anti Vietnam War protest turned riot in East Los Angeles – August

1971

- East LA Riots, January 31, East Los Angeles, California

- Bridgeport Riots, May 20–21, Bridgeport, Connecticut

- Chattanooga riot,[56] May 21–24, Chattanooga, Tennessee

- Albuquerque Riots,[57] June 13–14, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Oxnard Riots, July 19, Oxnard, California

- Riverside Riots, August 8–9, Riverside, California

- Camden riots, August 19–22, Camden, New Jersey

1972

- Escambia High School riots; Pensacola, Florida

- Blackstone Park Riots, July 16–18, Boston, Massachusetts

Post-Civil Rights Era: 1974–1989

- Boston busing crisis

- Racial violence in Marquette Park, Chicago

1978

1980

- Miami riot 1980 – following the acquittal of four Miami-Dade Police officers in the death of Arthur McDuffie. McDuffie, an African-American, died from injuries sustained at the hands of four white officers trying to arrest him after a high-speed chase.

1985

- 1985: MOVE Bombing - May 13, 1985, the Philadelphia Police bombed a residential home occupied by the black militant anarcho-primitivist group MOVE.

1989

- 1989 Miami riot - was sparked after police officer William Lozano shot Clement Lloyd, who was fleeing another officer and trying to run over Officer Lozano on his motorcycle.

Since 1990

- 1991: Crown Heights riot – May – between West Indian immigrants and the area's large Hasidic Jewish community, over the accidental killing of a Guyanese immigrant child by an Orthodox Jewish motorist. In its wake, several Jews were seriously injured; one Orthodox Jewish man, Yankel Rosenbaum, was killed; and a non-Jewish man, allegedly mistaken by rioters for a Jew, was killed by a group of African-American men.

- 1991: Overtown, Miami – In the heavily Black section against Cuban Americans, like earlier riots there in 1982 and 1984.

- 1991: 1991 Washington, D.C. riot – May – Riots following the shooting of a Salvadoran man by a police officer in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood, aggravated by grievances felt by Latinos in the district.

- 1992: 1992 Los Angeles riots – April 29 to May 5 – a series of riots, lootings, arsons and civil disturbance that occurred in Los Angeles County, California in 1992, following the acquittal of police officers on trial regarding the assault of Rodney King.

- 1995: St. Petersburg, Florida riot of 1996, caused by protests against racial profiling and police brutality.

- 2001: 2001 Cincinnati riots – April – in the African-American section of Over-the-Rhine.

- 2009: Oakland, CA – Riots following the BART Police shooting of Oscar Grant.

- 2012: Anaheim, California Riot—followed the shooting of two Hispanic males

- 2014: Ferguson, MO riots – Riots following the Shooting of Michael Brown

- 2015: 2015 Baltimore riots – Riots following the death of Freddie Gray

- 2015: Ferguson unrest – Riots following the anniversary of the Shooting of Michael Brown

- 2016: 2016 Milwaukee riots – Riots following the fatal shooting of 23 year old Sylville Smith.

- 2016: Charlotte riot, September 20–21, Riots started in response to the shooting of Keith Lamont Scott by police

- 2020: George Floyd protests - Ongoing riots sparked by the death of George Floyd by Officer Derek Chauvin of the Minneapolis Police Department, numerous disturbances broke out in other urban centers.

See also

- Apartheid

- Ghetto riots

- Jim Crow laws

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of race riots

- List of United States military history events

- Little Rock Nine

- Racial segregation in the United States

- Racism in the United States

- Timeline of riots and civil unrest in Omaha, Nebraska

- World timeline of race riots

References

- Madley, Benjamin (August 31, 2016). "Killing of Native Americans in California". C-SPAN. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- Wolf, Jessica (August 15, 2017). "Revealing the history of genocide against California's Native Americans". UCLA. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- Lewis, Guenter. "Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?". History News Network.

- On January 6, 1851 at his State of the State address to the California Senate, 1st Governor Peter Burnett said: "That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert."

- Burnett, Peter (6 January 1851). "State of the State Address". California State Library. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- Coffer, William E. (1977). "Genocide of the California Indians, with a Comparative Study of Other Minorities". The Indian Historian. San Francisco, CA. 10 (2): 8–15. PMID 11614644.

- Norton, Jack. Genocide in Northwestern California: 'When our worlds cried'. Indian Historian Press, 1979.

- Lynwood, Carranco; Beard, Estle (1981). Genocide and Vendetta: The Round Valley Wars of Northern California. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Lindsay, Brendan C. (2012). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846–1873. University of Nebraska Press.

- Johnston-Dodds, Kimberly (September 2002). Early California Laws and Policies Related to California Indians (PDF). Sacramento, CA: California State Library, California Research Bureau. ISBN 1-58703-163-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- Trafzer, Clifford E.; Lorimer, Michelle (2014). "Silencing California Indian Genocide in Social Studies Texts". American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (1): 64–82. doi:10.1177/0002764213495032.

- Madley, Benjamin (22 May 2016). "Op-Ed: It's time to acknowledge the genocide of California's Indians". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- "The Governor's Message (Transmitted January 7, 1851)," Sacramento Transcript, January 10, 1851, 2.

- On January 6, 1851 at his State of the State address to the California Senate, 1st Governor Peter Burnett used the following words: "That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert."

- "Militia and Indians". militarymuseum.org.

- Cowan, Jill (June 19, 2019). "'It's Called Genocide': Newsom Apologizes to the State's Native Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- "Minorities During the Gold Rush". California Secretary of State. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014.

- Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide, The United States and the California Catastrophe, 1846–1873. Yale University Press. pp. 11, 351. ISBN 978-0-300-18136-4.

- Castillo, Edward D. "California Indian History". California Native American Heritage Commission. Archived from the original on 2019-06-01.

- Richardson, Peter (10 October 2005). American Prophet: The Life and Work of Carey McWilliams. University of Michigan Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-472-11524-3.

White, Richard (16 February 2015). It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own: A New History of the American West. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-8061-7423-5. - Martone, Eric (12 December 2016). Italian Americans: The History and Culture of a People. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-1-61069-995-2.

- Villeneuve, Todd. "Racial Violence - Reconstruction Era - Intro". racialviolenceus.org. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- Villeneuve, Todd. "Racial Violence - Lynching Era - Intro.html". racialviolenceus.org. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- "Southern Manifesto". Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- Villeneuve, Todd. "Racial Violence - Modern Era - Intro". racialviolenceus.org. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- "The War on Drugs". Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- Reed, WL (1991). "Trends in Homicide Among African-Americans". Scholarworks.umb.edu – via Scholarworks.

- Zinn, 2004;, retrieved March 27, 2009.

- Bristow, D.L. (2002) A Dirty, Wicked Town. Caxton Press. p 253.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, History Matters, George Mason University

- Dray, 2002.

- Ellsworth, Scott. The Tulsa Race Riot, retrieved July 23, 2005.

- Hannah-Jones, Nikole (2015-03-04). "Yes, Black America Fears the Police. Here's Why". ProPublica. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- "Cincinnati Officer Is Acquitted in Killing That Ignited Unrest". The New York Times. September 27, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- "Shootings by Police Voted Top Story of 2014 in AP Poll". Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- "AP poll: Police killings of blacks voted top story of 2014". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Heim, Joe; Barrett, Devlin (June 27, 2018). "Man accused of driving into crowd at 'Unite the Right' rally charged with federal hate crimes". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- "Riot On Ward's Island.; Terrific Battle Between German and Irish Emigrants", New York Times, 06 March 1868

- "The Coal Riot. Horrible Treatment of the Laborers by the Miners. – Condition of the Wounded – A War of Races – Welsh vs. Irish and Germans," New York Times, 11 May 1871

- "New Orleans Police casualites [sic] 1874 "Liberty Place"". Afrigeneas.com. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- A Race Riot In Denver.; One Man Killed And A Number Of Heads Broken. New York Times. 12 Apr 1887

- Race Riot In Buffalo.; Italians and Irish Fight for an Hour and a Half in the Street. New York Times. 19 Mar. 1894

- Thomas J. Hudson, Iowa Chapter VIII, Events from Jackson to Cummins, The Province and the States, Vol. V, the Western Historical Association, 1904; page 170

- "The National Guard – Iowa's Splendid Militia," The Midland Monthly, Vol. II, No. 5 Nov. 1894; page 419.

- Service at Muchakinock and Evans, in Mahaska County, During the Coal Miners' Strike, Report of the Adjutant-General to the Governor of the State of Iowa for Biennial Period Ending Nov. 30, 1895, Conway, Des Moines, 1895; page 18

- "Race Riots in the U.S." www.infoplease.com. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- "Race Riots In Newburg.; Negroes Employed in Brick Yards Provoke Other Laborers -- Lively Battle Between the Factions," New York Times. 29 Jul. 1899

- "Argenta Race Riot", Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (accessed April 28, 2011).

- "Whites in Race War Kill Blacks Blindly". New York Times. 26 December 1906.

- Larsen, L. & Cotrell, B. (1997). The gate city: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. P 163.

- "July 29, 1910: Slocum Massacre in Texas - Zinn Education Project". zinnedproject.org. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Mack, Will. "The Chester, Pennsylvania Race Riot (1917)". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Race Riot of 1917 (Lexington, KY) · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". nkaa.uky.edu. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- Brian D. Greer, "John Carter (Lynching of)", Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, 2013

- "Albina Riot, 1967". The Oregon History Project. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- "150 Arrested in 2 Nights of Rioting in Chattanooga". The New York Times. 1971-05-23. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- Waldron, Martin (1971-06-20). "Albuquerque Divided Over Cause of First Major Riot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

Further reading

- Bloombaum, M. "The conditions underlying race riots as portrayed by multidimensional scalogram analysis: A eanalysis of Lieberson and Silverman's data" American Sociological Review 1968, 33#1: 76–91.

- Brophy, A.L. Reconstructing the dreamland: The Tulsa race riot of 1921 (2002)

- Chicago Commission on Race Relations. The Negro in Chicago: A study of race relations and a race riot (1922)

- Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, New York: Random House, 2002.

- Gilje, Paul A. Rioting in America (1996), examines 4000 American riots.

- Graham, . Hugh D. and Ted R Gurr, eds. The History of Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives (1969) (A Report Submitted to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence)

- Grimshaw, Allen D. "Lawlessness and violence in America and their special manifestations in changing negro-white relationships." Journal of Negro History 44.1 (1959): 52–72. online

- Grimshaw, Allen, ed. A social history of racial violence (2017).

- Grimshaw, Allen D. "Changing patterns of racial violence in the United States." Notre Dame Law Review. 40 (1964): 534+ online

- Gottesman, Ronald, ed. Violence in America: An Encyclopedia (3 vol 1999)

- Hofstadter, Richard, and Michael Wallace, eds. American violence: A documentary history (1970).

- Ifill, Sherrilyn A. On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-first Century (Beacon Press, 2007) ISBN 978-0-8070-0987-1

- Rable, George C. But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (1984)

- Rapoport, David C. "Before the bombs there were the mobs: American experiences with terror." Terrorism and Political Violence 20.2 (2008): 167–194. online

- Sowell, Thomas. Ethnic America: A History. 1981: Basic Books, Inc.

- Williams, John A. "The Long Hot the Summers of Yesteryear," History Teacher 1.3 (1968): 9–23. online

- Zinn, Howard. Voices of a People's History of the United States. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2004.

External links

- Revolution '67 – Documentary about the Newark, New Jersey, race riots of 1967

- Uprisings Urban riots of the 1960s.

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

- Lynchings: By State and Race, 1882–1968