Salyut 1

Salyut 1 (DOS-1) (Russian: Салют-1) was the first space station of any kind, launched into low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on April 19, 1971. The Salyut program followed this with five more successful launches of seven more stations. The final module of the program, Zvezda (DOS-8) became the core of the Russian segment of the International Space Station and remains in orbit.

Salyut 1 as seen from the departing Soyuz 11 | |

| |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1971-032A |

| SATCAT no. | 05160 |

| Call sign | Salyut 1 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Launch | April 19, 1971, 01:40:00 UTC[1] |

| Carrier rocket | Proton-K |

| Launch pad | Site 81/24, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Soviet Union |

| Reentry | October 11, 1971 |

| Mission status | De-orbited |

| Mass | 18,425 kg (40,620 lb) |

| Length | ~20 m (66 ft) |

| Diameter | ~4 m (13 ft) |

| Pressurized volume | 99 m3 (3,500 cu ft) |

| Perigee altitude | 200 km (124 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 222 km (138 mi) |

| Orbital inclination | 51.6 degrees |

| Orbital period | 88.5 minutes |

| Days in orbit | 175 days |

| Days occupied | 24 days |

| No. of orbits | 2,929 |

| Distance traveled | 118,602,524 km (73,696,192 mi) |

| Configuration | |

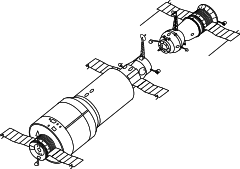

Soyuz docking with Salyut 1 | |

Background

Salyut 1 originated as a modification of the military Almaz space station program then in development.[2] After the landing of Apollo 11 on the Moon in July 1969, the Soviets began shifting the primary emphasis of their manned space program to orbiting space stations, with a possible lunar landing later in the 1970s if the N-1 booster became flight-worthy (it did not).[3] One other motivation for the space station program was a desire to one-up the US Skylab program then in development. The basic structure of Salyut 1 was adapted from the Almaz with a few modifications and would form the basis of all Soviet space stations through Mir.[2]

Civilian Soviet space stations were internally referred to as DOS (the Russian acronym for "Long-duration orbital station"), although publicly, the Salyut name was used for the first six DOS stations (Mir was internally known as DOS-7).[2] Several military experiments were nonetheless carried on Salyut 1, including the OD-4 optical visual ranger,[4] the Orion ultraviolet instrument for characterizing rocket exhaust plumes,[5] and the highly classified Svinets radiometer.[6]

Construction and operational history

Construction of Salyut 1 began in early 1970, and after nearly a year it was shipped to the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Some remaining assembly work had yet to be done, and this was completed at the launch center. The Salyut programme was managed by Kerim Kerimov,[7] chairman of the state commission for Soyuz missions.[8]

Launch was planned for April 12, 1971, to coincide with the 10th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's flight on Vostok 1, but technical problems delayed it until April 19.[9] The first crew launched later in the Soyuz 10 mission, but they ran into troubles while docking and were unable to enter the station; the Soyuz 10 mission was aborted and the crew returned safely to Earth. A replacement crew launched in Soyuz 11 and remained on board for 23 days. This was the first time in the history of spaceflight that a space station had been manned, and a new record time was set in space. This success was, however, short-lived when the crew was killed during re-entry, as a pressure-equalization valve in the Soyuz 11 re-entry capsule had opened prematurely, causing the crew to asphyxiate. They were the first and, as of 2020, the only humans to have died in space. After this accident, all missions were suspended while the Soyuz spacecraft was redesigned. The station was intentionally destroyed by de-orbiting after six months in orbit, because it ran out of fuel before a redesigned Soyuz spacecraft could be launched to it.[10]

Structure

At launch, the announced purpose of Salyut was to test the elements of the systems of a space station and to conduct scientific research and experiments. The craft was described as being 20 m (66 ft) in length, 4 m (13 ft) in maximum diameter, and 99 m3 (3,500 cu ft) in interior space with an on-orbit dry mass of 18,425 kg (40,620 lb). Of its several compartments, three were pressurized (100 m³ total), and two could be entered by the crew.[1]

Transfer compartment

The transfer compartment was equipped with the only docking port of Salyut 1, which allowed one Soyuz 7K-OKS spacecraft to dock. It was the first use of the Soviet SSVP docking system that allowed internal crew transfer, a system that is in use today. The docking cone had a 2 m (6.6 ft) front diameter and a 3 m (9.8 ft) aft diameter.[1]

Main compartment

The second and main compartment was about 4 m (13 ft) in diameter. Televised views showed enough space for eight large chairs (seven at work consoles), several control panels, and 20 portholes (some obstructed by instruments).[1] In Salyut 1 the interior design used various colors (light and dark gray, apple green, light yellow) for supporting the astronauts’ orientation in weightlessness.[11]

Auxiliary compartments

The third pressurized compartment contained the control and communications equipment, the power supply, the life support system, and other auxiliary equipment. The fourth and final unpressurized compartment was about 2 m in diameter and contained the engine installations and associated control equipment. Salyut had buffer chemical batteries, reserve supplies of oxygen and water, and regeneration systems. Externally mounted were two double sets of solar cell panels that extended like wings from the smaller compartments at each end, the heat regulation system's radiators, and orientation and control devices.[1]

Salyut 1 was modified from one of the Almaz airframes. The unpressurized service module was the modified service module of a Soyuz craft.[2]

Orion 1 Space Observatory

The astrophysical Orion 1 Space Observatory designed by Grigor Gurzadyan of Byurakan Observatory in Armenia, was installed in Salyut 1. Ultraviolet spectrograms of stars were obtained with the help of a mirror telescope of the Mersenne system and a spectrograph of the Wadsworth system using film sensitive to the far ultraviolet. The dispersion of the spectrograph was 32 Å/mm (3.2 nm/mm), while the resolution of the spectrograms derived was about 5 Å at 2600 Å (0.5 nm at 260 nm). Slitless spectrograms were obtained of the stars Vega and Beta Centauri between 2000 and 3800 Å (200 and 380 nm).[12] The telescope was operated by crew member Viktor Patsayev, who became the first man to operate a telescope outside the Earth's atmosphere.[13]

Specifications[2]

- Length – 15.8 m

- Maximum diameter – 4.15 m

- Habitable volume – 90 m³

- Mass at launch – 18,900 kg

- Launch vehicle – Proton (3–4 stages)

- Span across solar arrays – about 10 m

- Area of solar arrays – 28 m²

- Number of solar arrays – 4

- Resupply carriers – Salyut 1-type Soyuz (Redesigned Soyuz missions were to take place, but this did not occur)

- Number of docking ports – 1

- Total manned missions – 2

- Total long-duration manned missions – 1

Visiting spacecraft and crews

Soyuz 10

After taking 24 hours for rendezvous and approach, Soyuz 10 soft-docked with Salyut at 01:47 on April 24 (UTC) and remained for 5.5 h.[1] Hard-docking was unsuccessful due to technical malfunctions. The crew could not enter the station and had to abort the mission.[14]

| Expedition | Crew | Launch date | Flight up | Landing date | Flight down | Duration (days) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soyuz 10 | Vladimir Shatalov, Aleksei Yeliseyev and Nikolai Rukavishnikov | April 23, 1971 | Soyuz 10 | April 25, 1971 | Soyuz 10 | 0 | Failed docking |

Soyuz 11

.jpg)

Soyuz 11 took 3 hours and 19 minutes on June 7 to complete docking.[15] The crew transferred to Salyut and their mission was announced as:[1]

- Checking the design, units, onboard systems, and equipment of the orbital piloted station

- Testing the station's manual and autonomous procedures for orientation and navigation, as well as the control systems for maneuvering the space complex in orbit

- Studying Earth's surface geology, geography, meteorology, and snow and ice cover

- Studying physical characteristics, processes, and phenomena in the atmosphere and outer space in various regions of the electromagnetic spectrum

- Conducting medico-biological studies to determine the feasibility of having cosmonauts in the station perform various tasks, and studying the influence of space flight on the human organism.

On June 29, after 23 days and flying 362 orbits, the mission was cut short due to problems aboard the station, including an electrical fire. The crew transferred back to Soyuz 11 and reentered the Earth's atmosphere. The capsule parachuted to a soft landing in Kazakhstan, but the recovery team opened the hatch to find all three crew members dead in their couches. An inquest found that a pressure relief valve had malfunctioned during re-entry leading to a loss of cabin atmosphere.[16] The crew were not wearing pressure suits, and it was decreed that all further Soyuz missions would require the use of them.[17]

| Expedition | Crew | Launch date | Flight up | Landing date | Flight down | Duration (days) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soyuz 11 | Georgy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev, Vladislav Volkov | June 6, 1971, 04:55:09 UTC | Soyuz 11 | June 29, 1971, 23:16:52 UTC | Soyuz 11 | 23 days, 18 hours, 21 minutes, 43 seconds | Crew died on re-entry |

Re-entry

Salyut 1 was moved to a higher orbit in July–August 1971 to ensure that it would not be destroyed prematurely through orbital decay. In the meantime, Soyuz capsules were being substantially re-designed to allow pressure suits to be worn during launch, docking maneuvers, and re-entry.[18] The Soyuz redesign effort took too long however, and by September, Salyut 1 was running low on attitude control gas. It was decided to conclude the station's mission and on October 11, the main engines were fired for a deorbit maneuver. After 175 days, the world's first space station burned up over the Pacific Ocean.[1]

Pravda (October 26, 1971) reported that 75% of Salyut 1's studies were carried out by optical means and 20% by radio-technical means, while the remainder involved magnetometrical, gravitational, or other measurements. Synoptic readings were taken in both the visible and invisible parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.[1]

References

Citations

- "Salyut 1". NSSDC ID: 1971-032A. NASA. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Portree 1995.

- Baker 2007, p. 18.

- Ivanovich 2008, p. 9.

- Ivanovich 2008, p. 29.

- Oberg, James (December 18, 2016). "Have cosmonauts seen launches?" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Chladek, Jay (2017). Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-8032-2292-2.

- Ivanovich 2008, p. 56.

- McNamara, Bernard (2001). Into the Final Frontier: The Human Exploration of Space. Harcourt College Publishers. p. 223. ISBN 9780030320163.

- Shayler & Hall 2003, p. 179.

- Häuplik-Meusburger, Sandra (2011). Architecture for Astronauts: An Activity-based Approach. Vienna: Springer. p. 47. ISBN 9783709106679. OCLC 759926461.

- Gurzadyan, G. A.; Ohanesyan, J. B. (September 1972). "Observed Energy Distribution of α Lyra and β Cen at 2000–3800 Å". Nature. 239 (5367): 90. Bibcode:1972Natur.239...90G. doi:10.1038/239090a0.

- Marett-Crosby, Michael (June 28, 2013). Twenty-Five Astronomical Observations That Changed the World: And How To Make Them Yourself. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 282. ISBN 9781461468004. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Shayler & Hall 2003, p. 174.

- "Soyuz 11". NSSDC ID: 1971-035A. NASA. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Baker 2007, pp. 23–25.

- Shayler & Hall 2003, p. 180.

- Baker 2007, p. 25.

Sources

- Baker, Philip (2007). The Story of Manned Space Stations: An Introduction. Springer-Praxis Books in Astronomy and Space Sciences. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-30775-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivanovich, Grujica S. (2008). Salyut - The First Space Station: Triumph and Tragedy. Springer-Praxis Books in Astronomy and Space Sciences. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-73585-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Portree, David S. F. (March 1995). . . Johnson Space Center Reference Series. NASA. NASA Reference Publication 1357 – via Wikisource.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayler, David J.; Hall, Rex D. (2003). Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft. Springer-Praxis Books in Astronomy and Space Sciences. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 1-85233-657-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Salyut 1 chronology at Zarya.info