Cave of the Patriarchs

The Cave of the Patriarchs or Tomb of the Patriarchs, known to Jews as the Cave of Machpelah (Hebrew: מערת המכפלה, ![]()

![]()

Southern view | |

Shown within the West Bank | |

| Alternative name | Sanctuary of Abraham or Cave of Machpelah |

|---|---|

| Location | Hebron |

| Region | West Bank |

| Coordinates | 31.5247°N 35.1107°E |

| Type | tomb, mosque, synagogue[1] |

| History | |

| Cultures | Hebrew, Byzantine, Ayyubid, Crusaders, Ottoman |

Over the cave stands a large rectangular enclosure dating from the Herodian era.[2] Byzantine Christians took it over and built a Basilica which after the Muslim conquest was converted into the Ibrahimi Mosque. Crusaders took over the site in the 12th century, but it was taken back by Saladin 1188 and reconverted into a mosque.[3] Israel took control of the site in 1967, dividing the structure into a synagogue and a mosque.[4] In 1994, the Hebron massacre occurred in which a Jewish settler killed 29 Muslims praying in the mosque.

The Arabic name of the complex reflects the prominence given to Abraham in Islam. Outside biblical and Quranic sources there are a number of legends and traditions associated with the cave.[5]

The site is considered by Jews to be the second holiest place in the world, after the Temple Mount.[6]

Etymology of "Machpelah"

The etymology of the Hebrew name, Me'arat Machpelah, for the site is uncertain. The word Machpelah means "doubled", "multiplied" or "twofold" and Me'arat means "cave" so a literal translation would simply be "the double cave". The name could refer to the layout of the cave which is thought to consist of two or more connected chambers. This hypothesis is discussed in the tractate Eruvin from the 6th century Babylonian Talmud which cites an argument between two influential rabbis, Rav and Shmuel, debating over the layout of the cave:

Apropos this dispute, the Gemara cites similar disputes between Rav and Shmuel. With regard to the Machpelah Cave, in which the Patriarchs and Matriarchs are buried, Rav and Shmuel disagreed. One said: The cave consists of two rooms, one farther in than the other. And one said: It consists of a room and a second story above it. The Gemara asks: Granted, this is understandable according to the one who said the cave consists of one room above the other, as that is the meaning of Machpelah, double. However, according to the one who said it consists of two rooms, one farther in than the other, in what sense is it Machpelah? Even ordinary houses contain two rooms.[7]

The tractate continues by discussing another theory, that the name stems from it being the tomb of the three couples, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah, considered to be the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of the Abrahamic religions:[8][9]

Rather, it is called Machpelah in the sense that it is doubled with the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, who are buried there in pairs. This is similar to the homiletic interpretation of the alternative name for Hebron mentioned in the Torah: "Mamre of Kiryat Ha'Arba, which is Hebron" (Genesis 35:27). Rabbi Yitzḥak said: The city is called Kiryat Ha'Arba, the city of four, because it is the city of the four couples buried there: Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah.

Another theory holds that Machpelah didn't refer to the cave but rather was a large tract of land, The Machpelah, at the end of which the cave was found.[10] This theory is supported by some Bible verses such as Genesis 49:30, "the cave in the field of Machpelah, near Mamre in Canaan, which Abraham bought along with the field as a burial place from Ephron the Hittite." The question over the right interpretation of Machpelah has been discussed extensively in various Biblical commentaries.[11]

Biblical origin

According to Genesis 23:1–20, Abraham's wife Sarah dies in Kiryat Arba near Hebron in the land of Canaan at the age of 127, being the only woman in the Bible whose exact age is given, while Abraham is tending to business elsewhere. Abraham comes to mourn for her. After a while he stands up and speaks to the sons of Heth. He tells them that he is a foreigner in their land and requests that they give him a burial site so that he can bury his dead. The Hittites flatter Abraham, call him a Lord and mighty prince, and say that he can bury his dead in any of their tombs. Abraham doesn't take them up on their offer and instead asks them to contact Ephron the Hittite, the son of Zohar, who lives in Mamre and owns the cave of Machpelah which he is offering to buy for "the full price". Ephron slyly replies that he is prepared to give Abraham the field and the cave within it, knowing that it would not result in Abraham having a permanent claim to it.[12] Abraham politely refuses the offer and insists on paying for the field. Ephron replies that the field is worth four hundred shekels of silver and Abraham agrees to the price without any further bargaining.[12] He then proceeded to bury his dead wife Sarah there.[13]

The burial of Sarah is the first account of a burial[14] in the Bible, and Abraham's purchase of Machpelah is the first commercial transaction mentioned.

The next burial in the cave is that of Abraham himself, who at the age of 175 years was buried by his sons Isaac and Ishmael.[15] The title deed to the cave was part of the property of Abraham that passed to his son Isaac.[16][17] The third burial was that of Isaac, by his two sons Esau and Jacob, who died when he was 180 years old.[18] There is no mention of how or when Isaac's wife Rebecca died, only that she outlived her husband, but she is included in the list of those that had been buried in Machpelah in Jacob's final words to the children of Israel. Jacob himself died at the age of 147 years.[19]

In the final chapter of Genesis, Joseph had his physicians embalm his father Jacob, before they removed him from Egypt to be buried in the cave of the field of Machpelah.[20] When Joseph died in the last verse, he was also embalmed. He was buried much later in Shechem[21] after the children of Israel came into the promised land.

History

First and Second Temple Period

The time from which the Israelites regarded the site as sacred is unknown, though some scholars consider that the biblical story of Abraham's burial there probably dates from the 6th century BCE.[22][23]

In 31–4 BCE, the Jewish king Herod the Great built a large, rectangular enclosure over the cave to commemorate the site for his subjects.[24] It is the only fully surviving Herodian structure from the period of Hellenistic Judaism. Herod's building, with 6-foot-thick stone walls made from stones that were at least 3 feet (0.91 m) tall and sometimes reach a length of 24 feet (7.3 m), did not have a roof. Archæologists are not certain where the original entrance to the enclosure was located, or even if there was one.[24]

Byzantine Christian Period

Until the era of the Byzantine Empire, the interior of the enclosure remained exposed to the sky. Under Byzantine rule, a simple basilica was constructed at the southeastern end and the enclosure was roofed everywhere except at the centre.

During this period, the site became an important Christian pilgrimage destination. The Pilgrim of Bordaux, c. 333, reported "a monument of square form built of stone of wondrous beauty, in which lie Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Sara, Rebecca, and Leah".[25] The Piacenza Pilgrim (c. 570) noted in his pilgrimage account that Jews and Christians shared possession of the site.[26]

Arab period

In 614, the Sasanid Persians conquered the area and destroyed the castle, leaving only ruins; but in 637, the area came under the control of the Arab Muslims and the building was reconstructed as a roofed mosque.[27]

The Muslims permitted the building of two small synagogues at the site.[28]

During the 10th century, an entrance was pierced through the north-eastern wall, some way above the external ground level, and steps from the north and from the east were built up to it (one set of steps for entering, the other for leaving).[24] A building known as the qal'ah (قلعة i.e. castle) was also constructed near the middle of the southwestern side. Its purpose is unknown but one historic account claims that it marked the spot where Joseph was buried (see Joseph's tomb), the area having been excavated by a Muslim caliph, under the influence of a local tradition regarding Joseph's tomb.[24] Some archaeologists believe that the original entrance to Herod's structure was in the location of the qal'ah and that the northeastern entrance was created so that the kalah could be built by the former entrance.[24]

Crusader period

-LCCN2002724989.jpg)

In 1100, after the area was captured by the Crusaders, the enclosure once again became a church and Muslims were no longer permitted to enter. During this period, the area was given a new gabled roof, clerestory windows and vaulting.

When the Crusaders took control of the site Jews were banned from using the synagogues.[28]

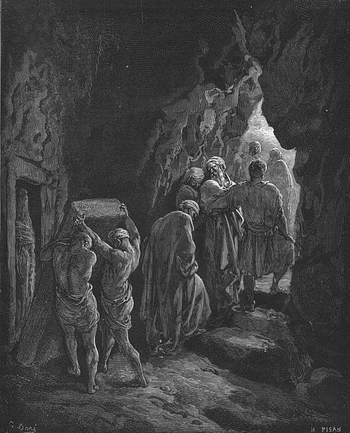

In the year 1113 during the reign of Baldwin II of Jerusalem, according to Ali of Herat (writing in 1173), a certain part over the cave of Abraham had given way, and "a number of Franks had made their entrance therein". And they discovered "(the bodies) of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob", "their shrouds having fallen to pieces, lying propped up against a wall...Then the King, after providing new shrouds, caused the place to be closed once more". Similar information is given in Ibn al Athir's Chronicle under the year 1119; "In this year was opened the tomb of Abraham, and those of his two sons Isaac and Jacob ...Many people saw the Patriarch. Their limbs had nowise been disturbed, and beside them were placed lamps of gold and of silver."[29] The Damascene nobleman and historian Ibn al-Qalanisi in his chronicle also alludes at this time to the discovery of relics purported to be those of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, a discovery that excited eager curiosity among all three communities in the southern Levant, Muslim, Jewish, and Christian.[30][31]

Towards the end of the period of Crusader rule, in 1166 Maimonides visited Hebron and wrote, "On Sunday, 9 Marheshvan (17 October), I left Jerusalem for Hebron to kiss the tombs of my ancestors in the Cave. On that day, I stood in the cave and prayed, praise be to God, (in gratitude) for everything."[32]

In 1170, Benjamin of Tudela visited the city, which he called by its Frankish name, St. Abram de Bron. He reported:

- "Here that there is the great church called St. Abram, and this was a Jewish place of worship at the time of the Mohammedan rule, but the Gentiles have erected there six tombs, respectively called those of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Leah. The custodians tell the pilgrims that these are the tombs of the Patriarchs, for which information the pilgrims give them money. If a Jew comes, however, and gives a special reward, the custodian of the cave opens unto him a gate of iron, which was constructed by our forefathers, and then he is able to descend below by means of steps, holding a lighted candle in his hand. He then reaches a cave, in which nothing is to be found, and a cave beyond, which is likewise empty, but when he reaches the third cave behold there are six sepulchres, those of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, respectively facing those of Sarah, Rebekah and Leah, upon which the names of the three Patriarchs and their wives are inscribed in Hebrew characters. The cave is filled with barrels containing bones of people, which are taken there as to a sacred place. At the end of the field of the Machpelah stands Abraham's house with a spring in front of it".[33][34]

Ayyubid period

In 1188 Saladin conquered the area, reconverting the enclosure to a mosque but allowing Christians to continue worshipping there. Saladin also added a minaret at each corner—two of which still survive—and the minbar.[24] Samuel ben Samson visited the cave in 1210; he says that the visitor must descend by twenty-four steps in a passageway so narrow that the rock touches him on either hand.[35]

Mamluk period

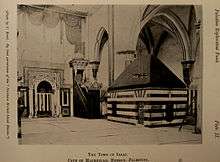

Between 1318 and 1320, the Mamluk, the governor of Gaza, a province that included Hebron, Sanjar al-Jawli ordered the construction of the Amir Jawli Mosque within the Haram enclosure to enlarge the prayer space and accommodate worshipers.[36] In the late 14th century, under the Mamluks, two additional entrances were pierced into the western end of the south western side and the kalah was extended upwards to the level of the rest of the enclosure. A cenotaph in memory of Joseph was created in the upper level of the kalah so that visitors to the enclosure would not need to leave and travel round the outside just to pay respects.[24] The Mamluks also built the northwestern staircase and the six cenotaphs (for Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob, Leah, Abraham, and Sarah, respectively), distributed evenly throughout the enclosure. The Mamluks forbade Jews from entering the site, allowing them only as close as the fifth step on a staircase at the southeast, but after some time this was increased to the seventh step.

Ottoman period

During the Ottoman period, the dilapidated state of the patriarchs' tombs was restored to a semblance of sumptuous dignity. Ali Bey, one of the few foreigners to gain access, reported in 1807 that,

all the sepulchres of the patriarchs are covered with rich carpets of green silk, magnificently embroidered with gold; those of the wives are red, embroidered in like manner. The sultans of Constantinople furnish these carpets, which are renewed from time to time. Ali Bey counted nine, one over the other, upon the sepulchre of Abraham.[37]

A contemporary traveller, M. Ermete Pierotti, in 1862 described the great jealousy with which the Muslims guard the sanctuary and the practice of sending petitions to the patriarchs:

The true entrance to the Patriarchs' tomb is to be seen close to the western wall of the enclosure, and near the north-west comer; it is guarded by a very thick iron railing, and I was not allowed to go near it. I observed that the Mussulmans themselves did not go very near it. In the court opposite the entrance gate of the Mosque, there is an opening, through which I was allowed to go down for three steps, and I was able to ascertain by sight and touch that the rock exists there, and to conclude it to be about five feet thick. From the short observations I could make during my brief descent, as also from the consideration of the east wall of the Mosque, and the little information I extracted from the Chief Santon, who jealously guards the sanctuary, I consider that a part of the grotto exists under the Mosque, and that the other part is under the court, but at a lower level than that lying under the Mosque. This latter must be separated from the former by a vertical stratum of rock which contains an opening, as I conclude, for two reasons : first, because the east wall being entirely solid and massive, requires a good foundation; secondly, because the petitions which the Mussulmans present to the Santon to be transmitted to the Patriarchs are thrown, some through one opening, some through the other, according to the Patriarch to whom they are directed; and the Santon goes down by the way I went, whence I suppose that on that side there is a vestibule, and that the tombs may be found below it. I explained my conjectures to the Santon himself after leaving the Mosque, and he showed himself very much surprised at the time, and told the Pacha afterwards that I knew more about it than the Turks themselves. The fact is that even the Pacha who governs the province has no right to penetrate into the sacred enclosure, where (according to the Mussulman legend) the Patriarchs are living, and only condescend to receive the petitions addressed to them by mortals.[38]

British mandate on Palestine

Jordanian control

After Jordan occupied the West Bank in 1948, no Jews were allowed in the territory and consequently no Jews could visit the tomb. In the 1960s, Jordan renovated the area surrounding the mosque, destroying several historical buildings in the process. Among them, the ruins of the nearby crusader fortress built in 1168.[39]

Israeli control

Following the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in the Six-Day War, Hebron came under Jewish control for the first time in 2,000 years and the 700-year-long restriction limiting Jews to the seventh step outside was lifted.[40]

According to the Chief Rabbi of the Israel Defense Forces, Major general Rabbi Shlomo Goren's autobiography on 8 June 1967, during the Six-day war, he made his way from Gush Etzion to Hebron. In Hebron he realized that the Arabs had surrendered and quickly made his way to the Cave of the Patriarchs. He shot at the doors of the mosque with his Uzi submachine gun. But when that was ineffective in prying the doors open, he attached chains to his Jeep and the doors, proceeding to pull them down. He entered the mosque and began to pray, becoming the first Jew to enter the compound for about 700 years. While praying, a messenger from the Mufti of Hebron delivered a surrender note to him, whereby the rabbi replied "This place, Ma'arat HaMachpela, is a place of prayer and peace. Surrender elsewhere."[41]

The first Jew to enter the underground caves was Michal Arbel, the 13-year-old daughter of Yehuda Arbel, chief of Shin Bet operations in the West Bank, because she was slender enough to be lowered into the narrow, 28 centimetres (11 in) wide hole on 9 October 1968, to gain access to the tomb site, after which she took photographs.[42]

Israeli settlers reestablished a small synagogue under the mosque. The first Jewish wedding ceremony to take place in it was on 7 August 1968.[43] The stone stairway leading to the mosque was also destroyed in order to erase the humiliating "seventh step".[1]

In 1968, a special arrangement was made to accommodate Jewish services on the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement. This led to a hand-grenade being thrown on the stairway leading to the tomb on 9 October; 47 Israelis were injured, 8 seriously.[44][45] On 4 November, a large explosion went off near the gate to the compound and 6 people, Jews and Arabs, were wounded.[45] On Yom Kippur eve, 3 October 1976, an Arab mob destroyed several Torah scrolls and prayer books at the tomb.[46] In May 1980, an attack on Jewish worshippers returning from prayers at the tomb left 6 dead and 17 wounded.[47]

In 1981, a group of Jewish settlers from the Hebron community lead by Noam Arnon broke into the caves and took photos of the burial chambers.[48]

Tensions would later increase as the Israeli government signed the Oslo Accords in September 1993, which gave limited autonomy to the PLO in the West Bank city of Jericho and the Gaza Strip. The city of Hebron and the rest of the major Palestinian population centers in the West Bank were not included in the initial agreement.[49] The Cave of the Patriarchs massacre committed by Baruch Goldstein, an Israeli-American settler in February 1994, left 29 Palestinian Muslims dead and scores injured. The resulting riots resulted in a further 35 deaths.

The increased sensitivity of the site meant that in 1996 the Wye River Accords, part of the Arab-Israeli peace process, included a temporary status agreement for the site restricting access for both Jews and Muslims. As part of this agreement, the waqf (Islamic charitable trust) controls 81% of the building. This includes the whole of the southeastern section, which lies above the only known entrance to the caves and possibly over the entirety of the caves themselves. In consequence, Jews are not permitted to visit the Cenotaphs of Isaac or Rebecca, which lie entirely within the southeastern section, except for 10 days a year that hold special significance in Judaism. One of these days is the Shabbat Chayei Sarah, when the Torah portion concerning the death of Sarah and the purchase by Abraham of the land in which the caves are situated, is read.

The Israeli authorities do not allow Jewish religious authorities the right to maintain the site and allow only the waqf to do so. Tourists are permitted to enter the site. Security at the site has increased since the Intifada; the Israel Defense Forces surround the site with soldiers and control access to the shrines. Israeli forces also subject locals to checkpoints and bar all non-Jews from setting foot on some of the main roads to the complex and ban Palestinian vehicles from many of the roads in the area.[50]

On 21 February 2010, Israel announced that it would include the site in a national heritage site protection and rehabilitation plan. The announcement sparked protests from the UN, Arab governments and the United States.[51][52] A subsequent UNESCO vote in October aimed to affirm that the "al-Haram al-Ibrahimi/Tomb of the Patriarchs in al-Khalil/Hebron" was "an integral part of the occupied Palestinian Territories."[53]

Israeli authorities have placed restrictions on calling the faithful to prayer by the muezzin of the Ibrahimi mosque. The order was enforced 61 times in October 2014, and 52 times in December of that year. This was following numerous complaints by the Jewish residents who claim that the calls violate legal decibel limits. In December 2009 Israeli authorities banned Jewish music played at the cave following similar complaints from the Arab residents.[54][55]

Structure

Building

The rectangular stone enclosure lies on a northwest-southeast axis, and is divided into two sections by a wall running between the northwestern three fifths, and the southeastern two fifths. The northwestern section is roofed on three sides, the central area and north eastern side being open to the sky; the southeastern section is fully roofed, the roof being supported by four columns evenly distributed through the section. Nearly the entire building itself was built by King Herod and it remains the only Herodian building surviving today virtually intact.[56][57][58]

In the northwestern section are four cenotaphs, each housed in a separate octagonal room, those dedicated to Jacob and Leah being on the northwest, and those to Abraham and Sarah on the southeast. A corridor runs between the cenotaphs on the northwest, and another between those on the southeast. A third corridor runs the length of the southwestern side, through which access to the cenotaphs, and to the southeastern section, can be gained. An entrance to the enclosure exists on the southwestern side, entering this third corridor; a mosque outside this entrance must be passed through to gain access.

At the center of the northeastern side, there is another entrance, which enters the roofed area on the southeastern side of the northwestern section and through which access can also be gained to the southeastern (fully roofed) section. This entrance is approached on the outside by a corridor which leads from a long staircase running most of the length of the northwestern side.[59] The southeastern section, which functions primarily as a mosque, contains two cenotaphs, symmetrically placed, near the center, dedicated to Isaac and Rebecca. Between them, in the southeastern wall, is a mihrab. The cenotaphs have a distinctive red and white horizontal striped pattern to their stonework but are usually covered by decorative cloth.

Under the present arrangements, Jews are restricted to entering by the southwestern side, and limited to the southwestern corridor and the corridors that run between the cenotaphs, while Muslims may enter only by the northeastern side but are allowed free rein of the remainder of the enclosure.

Caves

The caves under the enclosure are not themselves generally accessible; the waqf have historically prevented access to the actual tombs out of respect for the dead. Only two entrances are known to exist, the most visible of which is located to the immediate southeast of Abraham's cenotaph on the inside of the southeastern section. This entrance is a narrow shaft covered by a decorative grate, which itself is covered by an elaborate dome. The other entrance is located to the southeast, near the mihrab, and is sealed by a large stone, and usually covered by prayer mats; this is very close to the location of the seventh step on the outside of the enclosure, beyond which the Mamelukes forbade Jews from approaching.

When the enclosure was controlled by crusaders, access was occasionally possible. One account, by Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela dating from 1163 CE, states that after passing through an iron door, and descending, the caves would be encountered. According to Benjamin of Tudela, there was a sequence of three caves, the first two of which were empty; in the third cave were six tombs, arranged to be opposite to one another.[60]

These caves had been rediscovered only in 1119 CE by a monk named Arnoul, after an unnamed monk at prayer "noticed a draught" in the area near the present location of the mihrab and, with other "brethren", removed the flagstones and found a room lined with Herodian masonry.[61] Arnoul, still searching for the source of the draught, hammered on the cave walls until he heard a hollow sound, pulled down the masonry in that area, and discovered a narrow passage. The narrow passage, which subsequently became known as the serdab (Arabic for passage), was similarly lined with masonry, but partly blocked up. Having unblocked the passage, Arnoul discovered a large round room with plastered walls. In the floor of the room, he found a square stone slightly different from the others and, upon removing it, found the first of the caves. The caves were filled with dust. After removing the dust, Arnoul found bones; believing the bones to be those of the biblical Patriarchs, Arnoul washed them in wine and stacked them neatly. Arnoul carved inscriptions on the cave walls describing whose bones he believed them to be.[24]

This passage to the caves was sealed at some time after Saladin had recaptured the area, though the roof of the circular room was pierced, and a decorative grate was placed over it. In 1967, after the Six-Day War, the area fell into the hands of the Israel Defense Forces, and Moshe Dayan, the Defence Minister, who was an amateur archaeologist, attempted to regain access to the tombs. Ignorant of the serdab entrance, Dayan concentrated his attention on the shaft visible below the decorative grate and had the idea of sending someone thin enough to fit through the shaft and down into the chamber below. Dayan eventually found a slim 12-year-old girl named Michal to assist and sent her into the chamber with a camera.[62][63]

Michal explored the round chamber, but failed to find the square stone in the floor that led to the caves. Michal did, however, explore the passage and find steps leading up to the surface, though the exit was blocked by a large stone (this is the entrance near the mihrab).[24] According to the report of her findings, which Michal gave to Dayan after having been lifted back through the shaft, there are 16 steps leading down into the passage, which is 1 cubit wide, 17.37 metres (57.0 ft) and 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) high. In the round chamber, which is 12 metres (39 ft) below the entrance to the shaft, there are three stone slabs, the middle of which contains a partial inscription of Sura 2, verse 255, from the Quran, the famous Ayatul Kursi, Verse of the Throne.[24]

In 1981 Seev Jevin, the former director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, entered the passage after a group of Jewish settlers from Hebron had entered the chamber via the entrance near the mihrab and discovered the square stone in the round chamber that concealed the cave entrance. The reports state that after entering the first cave, which seemed to Jevin to be empty, he found a passage leading to a second oval chamber, smaller than the first, which contained shards of pottery and a wine jug.[64]

Religions beliefs and traditions

Judaism

According to the Book of Genesis, Abraham specifically purchased the land for use as a burial plot from Ephron the Hittite, making it one of two purchases by Abraham of real estate in the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land. The book describes how the three patriarchs and their wives, the matriarchs, were buried there.

- Abraham and Sarah (Genesis 23:1–20; Genesis 49:31)

- Isaac and Rebekah (Genesis 35:29; Genesis 49:31)

- Jacob and Leah (Genesis 49:28–33; Genesis 50:4–5; Genesis 50:12–13)

The only matriarch missing is Jacob's other wife, Rachel, described in Genesis[65] as having been buried near Bethlehem.[66] These verses are the common source for the religious beliefs surrounding the cave. While they are not part of the Quran they exist in Islam's oral tradition. The story of Abraham's burial is recounted in, for example, Ibn Kathir's 14th century Stories of the Prophets.

Jewish midrashic literature avows that, in addition to the patriarch couples, Adam, the first man, and his wife, Eve, were also interred in the Cave of the Patriarchs,[67] a tradition supported by ancient Samaritan texts.[68] The tradition is supported by the simple wording of Genesis 23:2, which refers to "Kiryat Arba... Hevron" ("arba" means four). Commenting on that passage, Rashi listed the four couples chronologically, starting with Adam and Eve.

Another Jewish tradition tells that when Jacob was brought to be buried in the cave, Esau prevented the burial, claiming that he had the right to be buried in the cave; after some negotiation Naphtali was sent to Egypt to retrieve the document stating Esau sold his part in the cave to Jacob. As this was going on, Hushim, the son of Dan, and who was hard of hearing, did not understand what was transpiring, and why his grandfather was not being buried, so he asked for an explanation; after being given one he became angry and said: "Is my grandfather to lie there in contempt until Naphtali returns from the land of Egypt?" He then took a club and killed Esau, and Esau's head rolled into the cave.[69] This implies that the head of Esau is also buried in the cave. Some Jewish sources record the selling of Esau's right to be buried in the cave — according to a commentary on the "Book of Exodus", Jacob gave all his possessions to acquire a tomb in the Cave of the Patriarchs. He put a large pile of gold and silver before Esau and asked, “My brother, do you prefer your portion of this cave, or all this gold and silver?”[70] Esau's selling to Jacob his right to be buried in the Cave of the Patriarchs is also recorded in Sefer HaYashar.[71]

An early Jewish text, the Genesis Rabba, states that this site is one of three that enemies of Judaism cannot taunt the Jews by saying "you have stolen them," as it was purchased "for its full price" by Abraham.[72]

According to the Midrash, the Patriarchs were buried in the cave because the cave is the threshold to the Garden of Eden. The Patriarchs are said not to be dead but "sleeping". They rise to beg mercy for their children throughout the generations. According to the Zohar,[73] this tomb is the gateway through which souls enter into Gan Eden, heaven.

There are Hebrew prayers of supplication for marriage on the walls of the Sarah cenotaph.

Islam

Muslims believe that Muhammed visited Hebron on his nocturnal journey from Mecca to Jerusalem to stop by the tomb and pay his respects.[74] For this reason the tomb quickly became a popular Islamic pilgrimage site. It was said that Muhammad himself encouraged the activity, saying "He who cannot visit me, let him visit the Tomb of Abraham" and "He who visits the Tomb of Abraham, Allah abolishes his sins."[5]

According to one tradition, childless women threw petitions addressed to Sarah, known for giving birth at an advanced age, through a hole in the mosque floor to the caves below.[75]

After the conquest of the city by Umar, this holy place was "simply taken over from the Jewish tradition"[76] by the new rulers; the Herodian enclosure was converted into a mosque and placed under the control of a waqf. The waqf continues to maintain most of the site, while the Israeli military controls access to the site.

According to some Islamic sources the cave is also the tomb of Joseph. Though the Bible has Joseph buried in Shechem (the present-day Palestinian city of Nablus), Jewish aggadic tradition conserved the idea that he wished to be interred at Hebron, and the Islamic version may reflect this.[77] The Jewish apocryphal book, The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, also states that this is the burial place of Jacob's twelve sons.[78]

According to some sources, the mosque is the 4th holiest in Islam,[79][80][81] other sources rank other sites as 4th.[82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93]

A Fatimid-era minbar is kept at the Mosque. According to an Arabic inscription written on the mimbar Fatimid vizier Badr al-Jamali had built this mimbar during the period of 18th Fatimid Imam al-Mustansir when he discovered the head of Husayn ibn Ali in 448 (A.H) at Ashkelon and, kept it in Mosque there.[94][95][96]

See also

- Burial places of founders of world religions

- List of World Heritage Sites in Palestine

- The Cave (opera)

- Tomb of the Matriarchs

References

- K..A. Berney; Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson, eds. (1996). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 338. ISBN 978-1134259939.

- Jacobsson, David M. (2000). "Decorative Drafted-margin Masonry in Jerusalem and Hebron and its Relations". The Journal of the Council for British Research in the Levant. 32: 135–54. doi:10.1179/lev.2000.32.1.135.

- "In Hebron, Israelis and Palestinians share a holy site ... begrudgingly". PRI. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Hammond, Constance A. Shalom/Salaam/Peace: A Liberation Theology of Hope. p. 37.

- Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitliz, David Martin. Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland: an Encyclopedia, Vol 1. p. 91.

- Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies, and Militance, University of Chicago Press, edited by Martin E. Marty, R. Scott Appleby, chapter authored by Ehud Sprinzak, p. 472

- "Eruvin 53a". Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Unesco declares Hebron's Old City Palestinian World Heritage site". BBC. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Krazovec, Joze (8 September 2010). The Transformation of Biblical Proper Names. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9780567429902. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Merrill, Selah (1890). "The Cave of Machpelah". The Old and New Testament Student. 11 (6): 327–335. doi:10.1086/470621. JSTOR 3157472.

- "Genesis 23:9". Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "A Burial Plot for Sarah (Genesis 23:1–20)". Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Genesis 23:9–20

- Easton's Bible Dictionary "Burial"

- Genesis 25:7–8 Hebrews 11:9

- Genesis 25:5–6

- Easton's Bible Dictionary "Machpelah"

- Genesis 35:28–29

- Genesis 47:28

- Genesis 50:1–14

- Joshua 24:32

- Niesiolowski-Spano, Lukasz (2014). The Origin Myths and Holy Places in the Old Testament. New York: Routledge. p. 120. ISBN 978-1845533342.

- Na'aman, Nadav (2005). "The 'Conquest of Canaan' in the Book of Joshua and in History". Canaan in the Second Millennium B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. p. 374.

The story reflects a time when Hebron was settled by non-Israelites, following the exile or desertion after 587/586 BCE. One may safely assume that it was composed to justify the rights of the post-Exilic community to the burial site in the former Judahite city of Hebron.

- Nancy Miller (May–June 1985). "Patriarchal Burial Site Explored for First Time in 700 Years". Biblical Archaeology Society. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Palestine Pilgrims Text Society (1887). Itinerary from Bordeaux to Jerusalem. Translated by Aubrey Stewart. p. 27.

- Avni, Gideon (2014). "Prologue: Four Eyewitness Accounts versus 'Arguments in Stone'". The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199684335.

- Mann, Sylvia (1 January 1983). "This is Israel: pictorial guide & souvenir". Palphot Ltd. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2015 – via Google Books.

- Norman Roth (2005). Daily Life of the Jews in the Middle Ages. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0313328657.

- Le Strange 1890, pp. 317–18 = p. 317, p. 318.

- Kohler 1896, pp. 447ff.

- Runciman & 1965 (b), p. 319.

- Kraemer 2001, p. 422.

- "Itinerary," ed. Asher, pp. 40–42, Hebr.

- Another translation: Wright, Thomas (1848). Early Travels in Palestine: Comprising the Narratives of Arculf, Willibald, Bernard, Saewulf, Sigurd, Benjamin of Tudela, Sir John Maundeville, de. p. 86. "The Gentiles have erected six sepulchres in this place, which they pretend to be those of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Leah. The pilgrims are told that they are the sepulchres of the fathers, and money is extorted from them. But if any Jew comes, who gives an additional fee to the keeper of the cave, an iron door is opened, which dates from the time of our forefathers who rest in peace, and with a burning candle in his hands, the visitor descends into a first cave, which is empty, traverses a second in the same state, and at last reaches a third, which contains six sepulchres, those of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and of Sarah, Rebekah, and Leah, one opposite the other. All these sepulchres bear inscriptions, the letters being engraved. Thus, upon that of Abraham we read: – "This is the sepulchre of our father Abraham; upon " whom be peace," and so on that of Isaac, and upon all the other sepulchres. A lamp burns in the cave and upon the sepulchres continually, both night and day, and you there see tombs filled with the bones of Israelites—for unto this day it is a custom of the house of Israel to bring hither the bones of their saints and of their forefathers, and to leave them there."

- "Pal. Explor. Fund," Quarterly Statement, 1882, p. 212).

- Dandis, Wala. History of Hebron Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 7 November 2011. Retrieved on 2 March 2012.

- Conder 1830, p. 198. The source was a manuscript, The Travels of Ali Bey, vol. ii, pp. 232–33.

- Stanley, Arthur. The Mosque of Hebron. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Alshweiky, Rabab; Gül Ünal, Zeynep (2016). "Patriarchs in Al-Khalil/Hebron". Journal of Cultural Heritage. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.02.014.

- "The Cave of Machpelah Tomb of the Patriarchs". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Hebron Liberation Day Celebrates Freedom of Worship". Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- "This Week in History: 1st Jew in Patriarch's Cave" Archived 12 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, by Tamara Zeve, Jerusalem Post, 7 October 2012

- Hoberman, Haggai (2008). Keneged Kol HaSikuim [Against All Odds] (in Hebrew) (1st ed.). Sifriat Netzaim.

- Esther Rosalind Cohen (1985). Human rights in the Israeli-occupied territories, 1967–1982. Manchester University Press ND. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7190-1726-1. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Dishon (1973). Middle East Record 1968. John Wiley and Sons. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-470-21611-8. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Mati Alon (2003). The Unavoidable Surgery. Trafford Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-4120-1004-7. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Ervin Birnbaum (1990). In the shadow of the struggle. Gefen Publishing House Ltd. p. 286. ISBN 978-965-229-037-3. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Entering the Cave of Machpela". Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- William Quandt, Peace Process 3rd edition, (Brookings Institution and University of California Press, 2005): 321–29.

- "Separation policy in Hebron: Military renews segregation on main street; wide part – for Jews, narrow, rough side passage – for Palestinians". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Israel to include West Bank shrines in heritage plan". Reuters. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "US slams Israel over designating heritage sites". Haaretz. 24 February 2010. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- "Executive Board adopts five decisions concerning UNESCO's work in the occupied Palestinian and Arab Territories". unesco.org. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "'Loudspeaker war' in Hebron". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- 'Israel banned call to prayer at Ibrahimi mosque 52 times in December,' Archived 4 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Ma'an News Agency 4 January 2015.

- Herod: King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans By Peter Richardson p. 61

- The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible By Bruce Manning Metzger, Michael David Coogan p. 99

- "Tombs of the Patriarchs – Hebron, State of Palestine". www.sacred-destinations.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- "a floorplan". Archived from the original on 20 October 2006.

- International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

- The Sunday at Home, Volume 31. Religious Tract Society. 1884. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Note: English translation based on a paper by Count Riant, "L'Invention de la Sépulture des Patriarches Abraham, Isaac et Jacob à Hébron, le 25 juin 1119," issued by the Société de l'Orient Latin, 1883.

- "photograph of Michal descending through the grated shaft". Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- Joseph Free and Howard F. Vos (1992) Archaeology and Bible History Zondervan, ISBN 0-310-47961-4 p. 62

- Der Spiegel, 52/2008 Title Story: Abraham, p. 104

- Genesis 35:19–20

- "Cave of Machpelah". Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- Jerusalem Talmud, Taanith 4:2; Babylonian Talmud, Erubin 53a; Pirke Rebbe Eliezer, chapter 20; Midrash Rabba (Genesis Rabba), ch. 28:3

- The Asatir (ed. Moses Gaster), The Royal Asiatic Society: London 1927, pp. 210, 212

- Sefaria. "Talmud Bavli, Sotah 13a". www.sefaria.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "Shemot Rabbah" 31:17

- Sefer Hayashar Chapter 27 p. 77b

- Genesis Rabba 79.7: "And he bought the parcel of ground, where he had spread his tent... for a hundred pieces of money." Rav Yudan son of Shimon said: ‘This is one of the three places where the non-Jews cannot deceive the Jewish People by saying that they stole it from them, and these are the places: Ma’arat HaMachpela, the Temple and Joseph's burial place. Ma’arat HaMachpela because it is written: ‘And Abraham hearkened unto Ephron; and Abraham weighed to Ephron the silver,’ (Genesis, 23:16); the Temple because it is written: ‘So David gave to Ornan for the place,’ (I Chronicles, 21:26); and Joseph's burial place because it is written: ‘And he bought the parcel of ground... Jacob bought Shechem.’ (Genesis, 33:19)." See also: Kook, Abraham Isaac, Moadei Hare'iya, pp. 413–15.

- Zohar 127a

- Vitullo, Anita (2003). "People Tied to Place: Strengthening Cultural Identity in Hebron's Old City". Journal of Palestine Studies. 33: 68–83. doi:10.1525/jps.2003.33.1.68.

- Bishop, Eric F. F (1948). "Hebron, City of Abraham, the Friend of God". Journal of Bible and Religion. 16 (2): 94–99. JSTOR 1457287.

- Hastings, Adrian, "Holy lands and their political consequences", Nations and Nationalism, Volume 9, Issue 1, pp. 29–54, January 2003.

- Shalom Goldman, The Wiles of Women/the Wiles of Men: Joseph and Potiphar's Wife in Ancient Near Eastern, Jewish, and Islamic Folklore, SUNY Press, 1995 pp. 126–27

- "The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs (R. H. Charles)". Earlychristianwritings.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Har-El, Shai (2014). "The Gate of Legacy". Where Islam and Judaism Join Together. pp. 69–86. doi:10.1057/9781137388124_6. ISBN 978-1-349-48283-2.

Hebron is regarded by the Jews as second in sanctity to Jerusalem, and by the Muslims as the fourth-holiest city after Mecca.

- Alshweiky, Rabab; Gül Ünal, Zeynep (2016). "An approach to risk management and preservation of cultural heritage in multi identity and multi managed sites: Al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi/Abraham's Tombs of the Patriarchs in Al-Khalil/Hebron". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 20: 709–14. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.02.014.

According to the Islamic belief, Al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi/Tombs of the Patriarchs is considered to be the fourth most important religious site in Islam after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem and the second holiest place after the Aqsa Mosque in Palestine. Additionally, according to the Jewish belief, it is the world's most ancient Jewish site and the second holiest place for the Jews, after Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

- Sellic, Patricia (1994). "The Old City of Hebron: Can It be Saved?". Journal of Palestine Studies. 23 (4): 69–82. doi:10.2307/2538213. JSTOR 2538213.

This deterioration has long-term implications for the Palestinians, since the old city of Hebron forms an important part of the Palestinian and indeed the Muslim heritage. It is one of the four holiest cities in Islam, along with Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem.

- Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia, edited by Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley, ABC CLIO, p. 121

- Damascus: What’s Left Archived 4 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Sarah Birke, New York Review of Books

- Totah, Faedah M. "Return to the origin: negotiating the modern and unmodern in the old city of Damascus." City & Society 21.1 (2009): 58–81.

- Berger, Roni. "Impressions and thoughts of an incidental tourist in Tunisia in January 2011." Journal of International Women's Studies 12.1 (2011): 177–78.

- Nagel, Ronald L. "Jews of the Sahara." Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine 21.1 (2016): 25–32.

- Harris, Ray, and Khalid Koser. "Islam in the Sahel." Continuity and Change in the Tunisian Sahel. Routledge, 2018. 107–20.

- Jones, Kevin. "Slavs and Tatars: Language arts." ArtAsiaPacific 91 (2014): 141.

- Sultanova, Razia. From Shamanism to Sufism: Women, Islam and Culture in Central Asia. Vol. 3. IB Tauris, 2011.

- Okonkwo, Emeka E., and C. A. Nzeh. "Faith–Based Activities and their Tourism Potentials in Nigeria." International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences 1 (2009): 286–98.

- Mir, Altaf Hussain. Impact of tourism on the development in Kashmir valley. Diss. Aligarh Muslim University, 2008.

- Desplat, Patrick. "The Making of a ‘Harari’ City in Ethiopia: Constructing and Contesting Saintly Places in Harar." Dimensions of Locality: Muslim Saints, Their Place and Space 8 (2008): 149.

- Harar – the Ethiopian city known as 'Africa's Mecca' Archived 4 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 21 July 2017

- Williams, Caroline. 1983. "The Cult of 'Alid Saints in the Fatimid Monuments of Cairo. Part I: The Mosque of al-Aqmar". In Muqarnas I: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Oleg Grabar (ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press, 37–52 [41], Wiet, "notes," pp. 217ff. RCEA, 7:260–63.

- Safarname Ibne Batuta.

- Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany & Shahadat al A'alamiyyah. Daily News, Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 2009 Archived 14 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cave of the Patriarchs. |

- Cave of the Patriarchs

- The Cave of Machpelah Tomb of the Patriarch Jewish Virtual Library

- Tombs of the Patriarchs Article and Photos Sacred Destinations

- Demands for Equal Rights for the Jewish People at Ma'arat HaMachpela Hebron.org.il

- Aerial Photograph Google Maps

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Bible Land Library

- Photos and Diagram of Underground at Caves of Machpela