MELAS syndrome

Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) is one of the family of mitochondrial cytopathies, which also include MERRF, and Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. It was first characterized under this name in 1984.[1] A feature of these diseases is that they are caused by defects in the mitochondrial genome which is inherited purely from the female parent.[2]

| Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes | |

|---|---|

| |

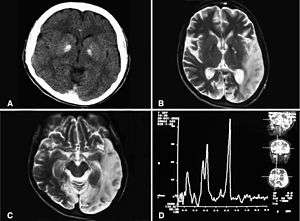

| Basal ganglia calcification, cerebellar atrophy, increased lactate; a CT image of a person diagnosed with MELAS | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Signs and symptoms

MELAS is a condition that affects many of the body's systems, particularly the brain and nervous system (encephalo-) and muscles (myopathy). In most cases, the signs and symptoms of this disorder appear in childhood following a period of normal development.[3] Early symptoms may include muscle weakness and pain, recurrent headaches, loss of appetite, vomiting, and seizures. Most affected individuals experience stroke-like episodes beginning before age 40. These episodes often involve temporary muscle weakness on one side of the body (hemiparesis), altered consciousness, vision abnormalities, seizures, and severe headaches resembling migraines. Repeated stroke-like episodes can progressively damage the brain, leading to vision loss, problems with movement, and a loss of intellectual function (dementia). The stroke-like episodes can be mis-diagnosed as epilepsy by a doctor who is not familiar with the MELAS condition.

Most people with MELAS have a buildup of lactic acid in their bodies, a condition called lactic acidosis. Increased acidity in the blood can lead to vomiting, abdominal pain, extreme tiredness (fatigue), muscle weakness, loss of bowel control, and difficulty breathing. Less commonly, people with MELAS may experience involuntary muscle spasms (myoclonus), impaired muscle coordination (ataxia), hearing loss, heart and kidney problems, diabetes, epilepsy, and hormonal imbalances.

The presentation of some cases is similar to that of Kearns–Sayre syndrome.[4]

Genetics

MELAS is mostly caused by mutations in the genes in mitochondrial DNA, but it can also be caused by mutations in the nuclear DNA.

NADH dehydrogenase

Some of the genes (MT-ND1, MT-ND5) affected in MELAS encode proteins that are part of NADH dehydrogenase (also called complex I) in mitochondria, that helps convert oxygen and simple sugars to energy.[6]

Transfer RNAs

Other genes (MT-TH, MT-TL1, and MT-TV) encode mitochondrial specific transfer RNAs (tRNAs).

Mutations in MT-TL1 cause more than 80 percent of all cases of MELAS. They impair the ability of mitochondria to make proteins, use oxygen, and produce energy. Researchers have not determined how changes in mitochondrial DNA lead to the specific signs and symptoms of MELAS. They continue to investigate the effects of mitochondrial gene mutations in different tissues, particularly in the brain.

Inheritance

This condition is inherited in a mitochondrial pattern, which is also known as maternal inheritance and heteroplasmy. This pattern of inheritance applies to genes contained in mitochondrial DNA. Because egg cells, but not sperm cells, contribute mitochondria to the developing embryo, only females pass mitochondrial conditions to their children. Mitochondrial disorders can appear in every generation of a family and can affect both males and females, but fathers do not pass mitochondrial traits to their children. In most cases, people with MELAS inherit an altered mitochondrial gene from their mother. Less commonly, the disorder results from a new mutation in a mitochondrial gene and occurs in people with no family history of MELAS.

Diagnosis

Treatment/prognosis

There is no curative treatment. The disease remains progressive and fatal.[7][8]

Patients are managed according to what areas of the body are affected at a particular time. Enzymes, amino acids, antioxidants and vitamins have been used.

Also the following supplements may help:

- CoQ10 has been helpful for some MELAS patients.[9] Nicotinamide has been used because complex l accepts electrons from NADH and ultimately transfers electrons to CoQ10.

- Riboflavin has been reported to improve the function of a patient with complex l deficiency and the 3250T-C mutation.[10]

- The administration of L-arginine during the acute and interictal periods may represent a potential new therapy for this syndrome to reduce brain damage due to impairment of vasodilation in intracerebral arteries due to nitric oxide depletion.[11][12]

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of MELAS is unknown.[13] It is one of the more common conditions in a group known as mitochondrial diseases.[13] Together, mitochondrial diseases occur in about 1 in 4,000 people.[13]

See also

References

- Pavlakis SG, Phillips PC, DiMauro S, De Vivo DC, Rowland LP (1984). "Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: a distinctive clinical syndrome". Ann Neurol. 16 (4): 481–8. doi:10.1002/ana.410160409. PMID 6093682.

- Hirano M, Pavlakis SG (1994). "Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS): current concepts". J Child Neurol. 9 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1177/088307389400900102. PMID 8151079.

- MELAS syndrome at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- Hirano M, Ricci E, Koenigsberger MR, Defendini R, Pavlakis SG, DeVivo DC, DiMauro S, Rowland LP (1992). "Melas: an original case and clinical criteria for diagnosis". Neuromuscul Disord. 2 (2): 125–35. doi:10.1016/0960-8966(92)90045-8. PMID 1422200.

- Abu-Amero KK, Al-Dhalaan H, Bohlega S, Hellani A, Taylor RW (2009). "A patient with typical clinical features of mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) but without an obvious genetic cause: a case report". J Med Case Rep. 3: 77. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-3-77. PMC 2783076. PMID 19946553.

- Tranchant, C.; Anheim, M. (2016). "Movement disorders in mitochondrial diseases". Revue Neurologique. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2016.07.003. ISSN 0035-3787.

- Quinn, NM; Stone, G; Brett, F; Caro-Dominguez, P; Neylon, O; Lynch, B. "MELAS (Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, Stroke) – a Diagnosis Not to be Missed". Irish Medical Journal.

- Muñoz-Guillén, N.; León-López, R.; Ferrer-Higueras, M.J.; Vargas-Vaserot, F.J.; Dueñas-Jurado, J.M. (August 2009). "Coma arrefléxico en el síndrome de MELAS" [Arreflexic coma and MELAS syndrome]. Revista Clínica Española (in Spanish). 209 (7): 337–341. doi:10.1016/s0014-2565(09)71818-1. PMID 19709537.

- Rodriguez MC, MacDonald JR, Mahoney DJ, Parise G, Beal MF, Tarnopolsky MA (2007). "Beneficial effects of creatine, CoQ10, and lipoic acid in mitochondrial disorders". Muscle Nerve. 35 (2): 235–42. doi:10.1002/mus.20688. PMID 17080429.

- Ogle RF, Christodoulou J, Fagan E, et al. (1997). "Mitochondrial myopathy with tRNA(Leu(UUR)) mutation and complex I deficiency responsive to riboflavin". J. Pediatr. 130 (1): 138–45. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70323-8. PMID 9003864.

- Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, et al. (2007). "MELAS and L-arginine therapy". Mitochondrion. 7 (1–2): 133–9. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.006. PMID 17276739.

- Hirata K, Akita Y, Povalko N, et al. (2007). "Effect of l-arginine on synaptosomal mitochondrial function". Brain Dev. 30 (4): 238–45. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2007.08.007. PMID 17889473.

- "MELAS". Genetics Home Reference. December 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |