McDonnell Douglas MD-80

The McDonnell Douglas MD-80 is a series of single-aisle airliners developed by McDonnell Douglas from the earlier DC-9. Stretched, heavier, and with higher bypass Pratt & Whitney JT8D-200 engines, the DC-9 Series 80 was launched in October 1977. It made its first flight on October 18, 1979 and was certified on August 25, 1980. It was first delivered to launch customer Swissair on September 13, 1980, which introduced it into commercial service on October 10, 1980.

| MD-80 series | |

|---|---|

| |

| An Iberia MD-88 in 2002 | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner |

| Manufacturer | McDonnell Douglas Boeing Commercial Airplanes (from Aug. 1997) SAIC (MD-82T) |

| First flight | October 18, 1979 |

| Introduction | October 10, 1980 with Swissair |

| Status | Production completed |

| Primary users | LASER Airlines Aeronaves TSM World Atlantic Airlines Bulgarian Air Charter[1] |

| Produced | 1979–1999 |

| Number built | 1,191 |

| Unit cost |

US$41.5–48.5 million |

| Developed from | McDonnell Douglas DC-9 |

| Variants | McDonnell Douglas MD-90 |

| Developed into | Boeing 717 Comac ARJ21 |

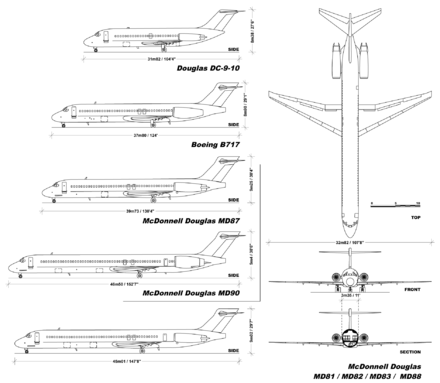

Keeping the five-abreast coach seating, longer variants are stretched by 14 ft (4.3 m) from the DC-9-50 and have a 28% larger wing. The long variants (MD-81/82/83/88) are 148 ft (45.1 m) long to seat 155 passengers in coach and, with varying weights, can cover up to 2,550 nmi (4,720 km). The later MD-88 has a modern cockpit with EFIS displays. The MD-87 is 17 ft (5.3 m) shorter for 130 passengers in economy and has a range up to 2,900 nmi (5,400 km).

It competed with the Boeing 737 Classic and the Airbus A320. Introduced in 1995, the MD-90 is a further stretch powered by IAE V2500 high-bypass turbofans, while the shorter MD-95, the later Boeing 717, was powered by Rolls-Royce BR715 engines. MD-80 production ended in 1999 after 1,191 were built.

Design and development

Background

.jpg)

Douglas Aircraft developed the DC-9 in the 1960s as a short-range companion to their larger DC-8.[2] The DC-9 was an all-new design, using two rear fuselage-mounted turbofan engines, and a T-tail. The DC-9 has a narrow-body fuselage design with five-abreast seating, and holds 80 to 135 passengers depending on seating arrangement and aircraft version.

The DC-9 family was produced in 2441 units: 976 DC-9s, 1191 MD-80s, 116 MD-90s, and 155 Boeing 717s.[3]

MD-80 series

The development of MD-80 series began in the 1970s as a lengthened, growth version of the DC-9-50, with a higher maximum take-off weight (MTOW) and a higher fuel capacity. Availability of newer versions of the Pratt & Whitney JT8D engine with higher bypass ratios drove early studies including designs known as Series 55, Series 50 (refanned Super Stretch), and Series 60. The design effort focused on the Series 55 in August 1977. With the projected entry into service in 1980, the design was marketed as the "DC-9 Series 80". Swissair launched the Series 80 in October 1977 with an order for 15 plus an option for five.[2]

The MD-80 is a mid-size, medium-range airliner. The series featured a fuselage 14 ft 3 in (4.34 m) longer than the DC-9-50. The DC-9's wing design was enlarged by adding sections at the wing root and tip for a 28% larger wing. It was the second generation of the DC-9, originally called the DC-9-80 and the DC-9 Super 80.[4] It has two rear fuselage-mounted turbofan engines, small, highly efficient wings, and a T-tail. The aircraft has five-abreast seating in the coach class. The aircraft series was designed for frequent, short-haul flights for 130 to 172 passengers depending on airplane version and seating arrangement.

The MD-80 versions have cockpit, avionics and aerodynamic upgrades along with the more powerful, more efficient and quieter JT8D-200 series engines, which are a significant upgrade over the smaller JT8D-15, -17, -11, and -9 series. The MD-80 series aircraft also have longer fuselages than their earlier DC-9 counterparts, as well as longer range. Some customers, such as American Airlines, still refer to the planes in fleet documentation as "Super 80". Comparable airliners to the MD-80 series include the Boeing 737-400 and Airbus A320.

Flight testing and certification

.jpg)

The first MD-80, DC-9 line number 909, made its first flight on October 18, 1979.[5] Although two aircraft were substantially damaged in accidents, test flying was completed on August 25, 1980, when the first variant of MD-80, the JT8D-209-powered MD-81 (or DC-9-81), was certified under an amendment to the FAA type certificate for the DC-9. The flight-testing leading up to certification had involved three aircraft accumulating a total of 1,085 flying hours on 795 flights. The first delivery, to launch customer Swissair took place on September 13, 1980.[6]

As the MD-80 was not in effect a new aircraft, it continues to be operated under an amendment to the original DC-9 FAA aircraft type certificate (a similar case to the later MD-90 and Boeing 717 aircraft). The type certificate issued to the aircraft manufacturer carries the aircraft model designations exactly as it appears on the manufacturer's application, including use of hyphens or decimal points, and should match what is stamped on the aircraft's data or nameplate. What the manufacturer chooses to call an aircraft for marketing or promotional purposes is irrelevant to the airworthiness authorities. The first amendment to the DC-9 type certificate for the new MD-80 aircraft was applied as DC-9-81, which approved on August 26, 1980. All MD-80 models have since been approved under additional amendments to the DC-9 type certificate. In 1983, McDonnell Douglas decided that the DC-9-80 (Super 80) would be designated the MD-80. Instead of merely using the MD- prefix as a marketing symbol, an application was made to again amend the type certificate to include the MD-81, MD-82, and MD-83. This change was dated March 10, 1986, and the type certificate declared that although the MD designator could be used in parentheses, it must be accompanied by the official designation, for example: DC-9-81 (MD-81). All Long Beach aircraft in the MD-80 series thereafter had MD-81, MD-82, or MD-83 stamped on the aircraft nameplate.

Although not certified until October 21, 1987, McDonnell Douglas had already applied for models DC-9-87 and DC-9-87F on February 14, 1985. The third derivative was similarly officially designated DC-9-87 (MD-87), although no nameplates were stamped DC-9-87. For the MD-88, an application for a type certificate model amendment was made after the earlier changes, so there was not a DC-9-88, which was certified on December 8, 1987.[7] The FAA's online aircraft registry database shows the DC-9-88 and DC-9-80 designations in existence but unused.[8]

Production

The second generation (later named MD-80s) was produced on a common line with the first generation DC-9s, with which it shares its line number sequence. After the delivery of 976 DC-9s and 108 MD-80s, McDonnell Douglas stopped DC-9 production. Hence, commencing with the 1,085th DC-9/MD-80 delivery, an MD-82 for VIASA in December 1982, all DC-9s produced were Series 80s/MD-80s.

.jpg)

In 1985, McDonnell Douglas, after years of negotiating attributed to Gareth C.C. Chang,[9] president of a McDonnell Douglas subsidiary, signed an agreement for joint production of MD-80s and MD-90s in the People's Republic of China. The agreement was for 26 aircraft, of which 20 were eventually produced along with two MD-90 aircraft.[10]

During 1991, MD-80 production had reached a peak of 12 per month, having been running at approximately 10 per month since 1987 and was expected to continue at this rate in the near term (140 MD-80s were delivered in 1991). As a result of the decline in the air traffic and a slow market response to the MD-90, MD-80 production was reduced, and 84 aircraft were handed over in 1992. A further production rate cut resulted in 42 MD-80s delivered during 1993 (3.5 per month) and 22 aircraft were handed over.[6] MD-80 production ended in 1999, with the final MD-80, an MD-83 registered as N984TW, being delivered to TWA.[11]

Derivative designs

_McDonnell_Douglas_demonstrator%2C_Farnborough_UK_-_England%2C_September_1988_(5589380211)_(cropped).jpg)

The MD-90 was developed from the MD-80 series and is a 5-foot-longer (1.5 m), updated version of the MD-88 with a similar electronic flight instrument system (EFIS) (glass cockpit), and improved, and quieter IAE V2500 high-bypass turbofan engines. The MD-90 program began in 1989, first flew in 1993, and entered commercial service in 1995.

Several other proposed variants never entered production. One proposal was the MD-94X, which was fitted with unducted fan turbofan engines. Previously, an MD-81 was used as a testbed for unducted fan engines, such as the General Electric GE36 and the Pratt & Whitney/Allison 578-DX.[12]

The MD-95 was developed to replace early DC-9 models, which were approaching 30 years of age. The project completely overhauled the original DC-9 into a modern airliner. It is slightly longer than the DC-9-30 and is powered by new Rolls-Royce BR715 engines. The MD-95 was renamed "Boeing 717" after the McDonnell–Douglas—Boeing merger in 1997.

Freighter conversions

In February 2010, Aeronautical Engineers Inc. (AEI) based in Miami, Florida announced it was beginning a freighter conversion program for the MD-80 series.[13] The converted aircraft use the "MD-80SF" designation. AEI was the first firm to receive a supplemental type certificate for the MD-80 family from the FAA in February 2013.[14] The first conversion was undertaken on an ex-American Airlines MD-82 aircraft, which was used as a testbed for the supplemental type.[15] The MD-80SF made its inaugural flight on 28 September 2012. AEI is certified to perform conversions on MD-81, MD-82, MD-83, and MD-88 aircraft. The launch customer for the conversion service is Everts Air Cargo.[13] In October 2015, the MD-80SF was approved by the EASA.[14] The first MD-80SF was delivered to Everts Air Cargo in February 2013.[16]

Operational history

The MD-80 series has been used by airlines around the world. Major customers have included Aerolíneas Argentinas, Aeroméxico, Aeropostal Aerorepublica, Alaska Airlines, Alitalia, Allegiant Air, American Airlines, Aserca, Austral Líneas Aéreas, Austrian Airlines, Avianca, China Eastern Airlines, China Northern Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Finnair, Iberia, Insel Air, Japan Air System (JAS), Korean Air, Lion Air, Martinair Holland, Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA), Reno Air, Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS), Spanair, Spirit Airlines, Swissair, Trans World Airlines and Meridiana.[17]

American Airlines was the first US major carrier to order the MD-80 when it leased twenty 142-seat aircraft from McDonnell Douglas in October 1982 to replace its Boeing 727-100s. It committed to 67 firm orders plus 100 options in March 1984, and in 2002 its fleet peaked at more than 360 aircraft, 30 % of the 1,191 produced. It announced that it would remove all of its MD-80s by 2019, replacing them with 737-800s.[18] The airline flew its final MD-80 revenue flights on September 3 and 4, 2019 before retiring its 26 remaining aircraft.[19] The final MD-80 flight on September 4, 2019 flew from Dallas/Fort Worth to Chicago–O'Hare.[20]

Due to the use of the aging JT8D engines, the MD-80 is not fuel efficient compared to the A320 or newer 737 models; it burns 1,050 US gal (4,000 l) of jet fuel per hour on a typical flight, while the larger Boeing 737-800 burns 850 US gal (3,200 l) per hour (19% reduction). Starting in the 2000s, many airlines began to retire the type. Alaska Airlines' tipping point in using the 737-800 was the $4 per gallon price of jet fuel the airline was paying by the summer of 2008; the airline stated that a typical Los Angeles-Seattle flight would cost $2,000 less, using a Boeing 737-800, than the same flight using an MD-80.[21]

Midwest Airlines announced on July 14, 2008, that it would retire all 12 of its MD-80s (used primarily on routes to the West Coast) by the fall.[22] The JT8D's comparatively lower maintenance costs due to simpler design help narrow the fuel cost gap.[23]

Variants

References: Flight International's Commercial Aircraft of the World 1981,[24] 1982,[25] 1983,[26] Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1994–1995,[27] and 2004-2005.[28]

Dimensions: The basic "long-body" MD-80 versions (MD-81, MD-82, MD-83, and MD-88) have an overall length of 147 ft 10 in (45.06 m), and a fuselage length of 136 feet 5 inches (41.58 m) that is 4.62 m longer than the DC-9-50 and 13.5 m longer than the initial DC-9, the Series 10. Wingspan was also increased by 4.4 m in comparison with earlier DC-9s at 107 feet 10.2 inches (32.873 m). The aircraft's passenger cabin, from cockpit door to aft bulkhead, is 101 feet 0 inches (30.78 m) long and, as with all versions of the DC-9, has a maximum cabin width (trim-to-trim) of 123.7 inches (3.14 m).

Powerplant: The initial production version of the MD-80 was the Pratt and Whitney JT8D-209 18,500 lbf (82 kN) thrust-powered MD-81. Later build MD-81s have been delivered with more powerful JT8D-217 and -219 engines.

APU: All versions of the MD-80 are equipped with an AlliedSignal (Garrett) GTCP85-98D APU as standard, which is located in the aft fuselage.

Flight deck: The MD-80 is equipped with a two crew flightdeck similar to that on the DC-9 from which it evolved. Later models could be equipped to a higher specification with EFIS displays in place of the traditional analogue instruments, TCAS, windshear detection, etc. An EFIS retrofit to non-EFIS-equipped aircraft is possible.

Cabin: Typical passenger-cabin seating arrangements include:[6]

- A mixed-class, with aft full-service galley, configuration for a total of 135 passengers with 12 first class, four-abreast 36-inch seat pitch.

- 123 economy-class passengers, five-abreast, 32-inch pitch.

- All-economy layout for 155 passengers, five-abreast, 32- and 33-inch pitch.

- A typical high-density layout is for 167 in one class (i.e., Airtours).

Undercarriage: All versions of the MD-80 are equipped with a tricycle undercarriage, featuring a twin nose unit with spray deflector and twin main units with rock deflectors. The MD-80T, developed for the Chinese, differs in that the main units are each fitted with a four-wheel double-main-bogey undercarriage to reduce pavement loading.[6][26]

Aerodynamic improvements: From mid-1987, new MD-87-style low-drag "beaver" tail cones were introduced on all series of MD-80s, reducing drag and improving fuel burn. Some operators have been modifying the old DC-9-style cones on earlier-build MD-80s to the new low-drag style. Scandinavian Airlines System has done this, citing the improved economics and cosmetics from the modification.[6]

MD-81

The MD-81 (originally known as the DC-9 Super 81 or DC-9-81) was the first production model of the MD-80, and apart from the MD-87, the differences between the various long-body MD-80 variants are relatively minor. The four long-body models (MD-81, MD-82, MD-83, and MD-88) only differ from each other in having different engine variants, fuel capacities, and weights. The MD-88 and later-build versions of the other models have more up-to-date flight decks featuring for example EFIS.

Performance: Standard maximum take-off weight (MTOW) on the MD-81 is 140,000 lb (63,500 kg) with the option to increase to 142,000 lb (64,400 kg). Fuel capacity is 5,840 US gallons (22,100 L), and typical range, with 155 passengers, is 1,565 nmi.[6]

MD-81 timeline

- Formal launch: October 1977

- First flight: October 18, 1979

- FAA certification: August 25, 1980

- First delivery: September 13, 1980 to Swissair

- Entry into service: October 10, 1980 with Swissair on a flight from Zurich to Heathrow.

- Last delivery: June 24, 1994 to JAL Domestic

MD-82

Announced on April 16, 1979, the MD-82 (DC-9-82) was a new MD-80 variant with similar dimensions to those of the MD-81 but equipped with more powerful engines. The MD-82 was intended for operation from 'hot and high' airports but also offered greater payload/range when in use at 'standard' airfields.[29] American Airlines was the world's largest operator of the MD-82, with at one point over 300 MD-82s in the fleet.

Originally certified with 20,000 lbf (89 kN) thrust JT8D-217s, a -217A-powered MD-82 was certified in mid-1982 and became available that year. The new version featured a higher MTOW (149,500 lb (67,800 kg)), while the JT8D-217As had a guaranteed take-off thrust at temperatures up to 29 °C (84 °F) or 5,000 ft (1,500 m) altitude. The JT8D-217C engines were also offered on the MD-82, giving improved Thrust specific fuel consumption (TSFC). Several operators took delivery of the -219-powered MD-82s, while Balair ordered its MD-82s powered by the lower-thrust -209 engine.[6][26]

The MD-82 features an increased standard MTOW initially to 147,000 lb (66,700 kg), and this was later increased to 149,500 lb (67,800 kg). Standard fuel capacity is the same as that of the MD-81, 5,840 US gal (22,100 L), and typical range with 155 passengers is 2,050 nmi (3,800 km).[6][26]

MD-82 timeline

- Announced/go-ahead: April 16, 1979

- First flight: January 8, 1981

- FAA certification: July 29, 1981

- First delivery: August 5, 1981 to Republic Airlines

- Entry into service: August, 1981 with Republic Airlines

- Last delivery: November 17, 1997 to U-Land Airlines of Taiwan

The MD-82 was assembled under license in Shanghai by the Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation (SAIC, today's COMAC) beginning in November 1986; the sub-assemblies were delivered by McDonnell Douglas in kit form.[6] China had begun design on a cargo version, designated Y-13, but the project was subsequently cancelled with the conclusion of the licensed assembly of the MD-82 and MD-90 in China.[30][31] In 2012, Aeronautical Engineers Inc. performed the first commercial-freighter conversion of an MD-82.[13]

MD-83

_-_Spanair_-_EC-FXA_-_LEMD_-_20050305.jpg)

The MD-83 (DC-9-83) is a longer-range version of the basic MD-81/82 with higher weights, more powerful engines, and increased fuel capacity.

Powerplant: Compared to earlier models, the MD-83 is equipped with slightly more powerful 21,000 lbf (93 kN)-thrust Pratt and Whitney JT8D-219s as standard.

Performance: The MD-83 features increased fuel capacity as standard (to 6,970 US gal (26,400 L)), which is carried in two 565 US gal (2,140 L) auxiliary tanks located fore and aft of the center section. The aircraft also has higher operating weights, with MTOW increased to 160,000 lb (73,000 kg) and MLW to 139,500 lb (63,300 kg). Typical range for the MD-83 with 155 passengers is around 2,504 nautical miles (4,637 km). To cope with the higher operating weights, the MD-83 incorporates strengthened landing gear including new wheels, tires, and brakes, changes to the wing skins, front spar web and elevator spar cap, and strengthened floor beams and panels to carry the auxiliary fuel tanks. From MD-80 line number 1194, an MD-81 delivered in September 1985, it is understood that all MD-80s have the same basic wing structure and in theory could be converted to MD-83 standard.[6]

MD-83 timeline

- Announced/go-ahead: January 31, 1983

- First flight: December 17, 1984

- FAA certification: October 17, 1985 (MTOW 149,500 lb (67,800 kg)). MTOW of 160,000 lb (73,000 kg) certified November 4, 1985.

- First delivery: February, 1985 to Alaska Airlines – initially as -82 powered by -217A engines and certified as MD-82s. Alaska Airlines' first four aircraft were subsequently re-engined and re-certified as MD-83s.

- Entry into service: February, 1985 with Alaska Airlines

- Last delivery: December 28, 1999 to TWA

MD-87

In January 1985, McDonnell Douglas announced it would produce a shorter-fuselage MD-80 variant, designated MD-87 (DC-9-87), which would seat between 109 and 130 passengers depending upon configuration. The designation was intended to indicate its planned date of entry into service, 1987.

Dimensions: With an overall length of 130 ft 5 in (39.75 m), the MD-87 is 17 ft 4 in (5.28 m) shorter than the other MD-80s but is otherwise generally similar to them, employing the same engines, systems and flight deck. The MD-87 features modifications to its tail, with a fin extension above the tailplane. It also introduced a new low-drag "beaver" tail cone, which became standard on all MD-80s.

Powerplant: The MD-87 was offered with either the 20,000 lbf (89 kN) thrust JT8D-217C or the 21,000 lbf (93 kN) thrust -219.

Performance: Two basic versions of the MD-87 were made available with either an MTOW of 140,000 lb (64,000 kg) and MLW of 128,000 lb (58,000 kg) or an MTOW of 149,000 lb (68,000 kg) and an MLW of 130,000 lb (59,000 kg). Fuel capacity is 5,840 US gal (22,100 l), increasing to 6,970 US gal (26,400 l) with the incorporation of two auxiliary fuel tanks. Typical range with 130 passengers, is 2,370 nmi (4,390 km) increasing to 2,900 nmi (5,400 km) with two auxiliary fuel tanks.

Cabin: The MD-87 provides typical mixed-class seating for 114 passengers or 130 in an all-economy layout (five-abreast 31 in and 32 in seat pitch). The maximum seating, exit-limited, is for 139 passengers.

MD-87 timeline

- Announced/go-ahead: January 1985

- First flight: December 4, 1986

- FAA certification: October 21, 1987

- First delivery: November 27, 1987 to Austrian Airlines[32]

- Last delivery: March 27, 1992 to Scandinavian Airlines (SAS)

MD-88

The MD-88 was the last variant of the MD-80, which was launched on January 23, 1986, on the back of orders and options from Delta Air Lines for a total of 80 aircraft.

The MD-88 is, depending on specification, basically similar to the MD-82 or MD-83 except it incorporates an EFIS cockpit instead of the more traditional analog flight deck of the other MD-80s. Other changes incorporated into the MD-88 include a wind-shear warning system and general updating of the cabin interior/trim. These detail changes are relatively minor and were written back as standard on the MD-82/83. The wind-shear warning system was offered as a standard option on all other MD-80s and has been made available for retrofitting on earlier aircraft including the DC-9.

Delta's initial eight aircraft were manufactured as MD-82s and upgraded to MD-88 specifications. MD-88 deliveries began in December 1987, and it entered service with Delta in January 1988. The final commercial flight of an MD-88 within the United States took place on June 2, 2020, by a Delta flight from Washington Dulles to Atlanta.[33]

Performance: The MD-88 has the same weight, range, and airfield performance as the other long-body aircraft (MD-82 and MD-83) and is powered by the same engines. MDC quotes a typical range for the MD-88 as 2,050 nmi (3,800 km) with 155 passengers. Adding two additional auxiliary fuel tanks increases, its 155-passenger range to 2,504 nmi (4,637 km) (similar to the MD-83). A Wall Street Journal article about the crash of Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 at New York City's LaGuardia Airport in March 2015 stated that "pilots and other safety experts have long known that when the MD-88's reversers are deployed, its rudder... sometimes may not be powerful enough to control deviations to the left or right from the center of a runway...safety board investigators, among other things, are looking to see if this tendency played any role in the crash..".[34]

MD-88 timeline

- Announced/go-ahead: January 23, 1986

- First flight: August 15, 1987

- FAA certification: December 8, 1987

- First delivery: December 19, 1987, to Delta Air Lines

- Entry into service: January 5, 1988, with Delta Air Lines

- Last delivery: June 25, 1997, to Onur Air

- Final commercial flight in the U.S.: June 2, 2020, by Delta Air Lines[33]

Undeveloped variants

MD-80 Advanced

McDonnell Douglas revealed at the end of 1990 that it would be developing an MD-80 improvement package with the intent to offer beginning in early 1991 for delivery from mid-1993. The aircraft became known as the MD-80 Advanced. The main improvement was the installation of Pratt & Whitney JT8D-290 engines with a 1.5 in larger diameter fan and would, it was hoped, allow a 6 dB reduction in exterior noise.

Due to lack of market interest, McDonnell Douglas dropped its plans to offer the MD-80 Advanced during 1991. Then in 1993, a "mark 2" MD-80 Advanced version reappeared with the modified JT8D-290 engines as previously proposed. The company also evaluated the addition of winglets on the MD-80. In late 1993, Pratt & Whitney launched a modified version of the JT8D-200 series, the -218B, which was being offered for the DC-9X re-engining program, and was also evaluating the possibility of developing a new JT8D for possible retrofit on the MD-80. The engine would also be available on new build MD-80s.

The 18,000 lbf (80 kN) to 19,000 lbf (85 kN) thrust -218B engine version shares a 98% commonality with the existing engine, with changes designed to reduce NOx, improve durability, and reduce noise levels by 3 dB. The 218B could be certified in early to mid-1996. The new engine, dubbed the "8000", was to feature a new fan of increased diameter (by 1.7 in), extended exhaust cone, a larger LP compressor, a new annular burner, and a new LP turbine and mixer. The initial thrust rating would be around 21,700 lbf (97 kN). A launch decision on the new engine was expected by mid-1994, but never occurred. The MD-80 Advanced was also to offer a new flight deck instrumentation package and a completely new passenger compartment design. These changes would be available by retrofit to existing MD-80s, and was forecast to enter service by July 1993.

The MD-80 Advanced was to incorporate the advanced flight deck of the MD-88, including a choice of reference systems, with an inertial reference system as standard fitting and optional attitude-heading equipment. It was to be equipped with an electronic flight instrument system (EFIS), an optional second flight management system (FMS), and light-emitting diode (LED) dot-matrix electronic engine and system displays. A Honeywell wind-shear computer and provision for an optional traffic-alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS) were also to be included. A new interior would have a 12% increase in overhead baggage space and stowage compartment lights that come on when the doors open, as well as new video system featuring drop-down LCD monitors above.[7]

The lack of market interest for the MD-80 Advanced during 1991 led McDonnell Douglas to drop its plans for the development.

MD-89

In 1984-1985, McDonnell Douglas proposed a 173-passenger, 152 in (390 cm; 12.7 ft; 3.9 m) stretch of the MD-80 called the MD-89, which would use the International Aero Engines V2500 engine instead of the regular JT8D-200 series engines.[35] The MD-89 was intended to have two 57 in (140 cm; 4.8 ft; 1.4 m) fuselage plugs forward of the wing and one 38 in (97 cm; 3.2 ft; 0.97 m) fuselage plug aft of the wing.[36] IAE and McDonnell Douglas announced an agreement to jointly market this 160 ft 6 in (48.9 m) derivative on February 1, 1985, but the concept was subsequently deprioritized in favor of the proposed MD-91 and MD-92 derivatives using ultra-high bypass (UHB) propfan engines. By 1989, however, lack of airline orders for the UHB derivatives caused McDonnell Douglas to return to the IAE V2500 engines to launch its MD-90 series aircraft.[2]

MD-90X

Starting in late 1986, McDonnell Douglas began offering the MD-90X, a 25 ft (7.6 m) stretch of the MD-80. Unlike the MD-91 and MD-92 derivatives and the clean-sheet MD-94X proposal, the MD-90X would still use turbofan engines. The MD-90X would carry 180 passengers.[37] Powered by the 26,500 lbf thrust (118 kN) CFM56-5 or V2500, the MD-90X replaced the MD-89 as McDonnell Douglas's proposed new turbofan offering, and it was designed to compete with the Boeing 757.[38]

P-9D

When the United States Navy wanted to replace its 125 Lockheed P-3 Orion anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft, McDonnell Douglas offered the P-9D, which would be a propfan-powered version of the MD-87 or MD-91. The 25,000 lbf (110 kN) thrust engine would be either the General Electric GE36 or the Pratt & Whitney/Allison 578-DX.[39] Lockheed won the competition with its P-3 derivative, the Lockheed P-7, but the replacement program was later canceled.

Operators

.jpg)

There are 151 MD-80 series aircraft in service as of June 2020, with operators including LASER Airlines (13), Aeronaves TSM (12), World Atlantic Airlines (11), and other carriers with smaller fleets.[40] In addition to passenger airlines, several MD-87s have been converted for aerial firefighting use by Aero Air/Erickson Aero Tanker.[41][42] American Airlines retired its MD-80 series aircraft after making its last commercial flight on September 4, 2019.[43] Delta Air Lines retired its MD-88 and MD-90 aircraft after making its last commercial flight on June 2, 2020.[44]

Deliveries

| Type | Total | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 | 1986 | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD-81 | 132 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 48 | 5 | |||||

| MD-82 | 539 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 18 | 48 | 48 | 37 | 51 | 50 | 64 | 55 | 43 | 50 | 23 | 13 | |||

| MD-82T | 30 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| MD-83 | 265 | 26 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 11 | 12 | 25 | 26 | 30 | 26 | 26 | 31 | 12 | 8 | |||||

| MD-87 | 75 | 5 | 13 | 25 | 15 | 14 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| MD-88 | 150 | 5 | 13 | 29 | 32 | 23 | 25 | 19 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Total | 1,191 | 26 | 8 | 16 | 12 | 18 | 23 | 43 | 84 | 140 | 139 | 117 | 120 | 94 | 85 | 71 | 44 | 51 | 34 | 61 | 5 |

Accidents and incidents

As of February 2018, the MD-80 series has been involved in 71 incidents,[46] including 35 hull-loss accidents,[47] with 1,446 fatalities of occupants.[48][49]

Notable accidents and incidents

- On December 1, 1981, Inex-Adria Aviopromet Flight 1308, MD-81 (YU-ANA), crashed into Corsica's Mt. San Pietro during a holding pattern for landing at Campo dell'Oro Airport, Ajaccio, France. All 180 passengers and crew were killed. This was the first-ever fatal incident involving the MD-80 series and also the deadliest.[50]

- On August 16, 1987, Northwest Airlines Flight 255, MD-82, crashed shortly after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport due to the flight crew's failure to use the taxi checklist to ensure that flaps and slats were extended for takeoff, according to the NTSB. All crew and passengers were killed, with the exception of a four-year-old girl, Cecelia Cichan. Two people on the ground were also killed.[51][52][53]

- On June 12, 1988, Austral Líneas Aéreas Flight 46, MD-81 N1003G, crashed short of the runway at Libertador General José de San Martín Airport, in Posadas, Misiones. All 22 passengers and crew were killed.[54]

- On December 27, 1991, SAS Flight 751, MD-81 OY-KHO "Dana Viking", crash-landed at Gottröra, Sweden. In the initial climb, both engines ingested ice broken loose from the wings (although they had been properly deiced before departure). The ice damaged the compressor blades causing compressor stall. The stall further caused repeated engine surges that finally destroyed both engines, leaving the aircraft with no thrust. The aircraft landed in a snowy field and broke into three parts. No fire occurred, and all aboard survived.

- On November 13, 1993, China Northern Airlines Flight 6901, MD-82 B-2141, crashed before landing at Ürümqi Diwopu International Airport in Xinjiang, China, killing twelve of the 102 passengers and crew on board.[55]

- On July 6, 1996, Delta Air Lines Flight 1288, an MD-88, attempting to take off from Pensacola Regional Airport experienced an uncontained, catastrophic turbine engine failure that caused debris from the front compressor hub of the number one left engine to penetrate the left aft fuselage. The penetrating debris left two passengers dead and two severely injured; all were from the same family. The pilot aborted takeoff, and the airplane stopped on the runway.

- On June 1, 1999, American Airlines Flight 1420, an MD-82, attempting to land in severe weather conditions at Little Rock Airport overshot the runway and crashed into the banks of the Arkansas River. Eleven people, including the captain, died.

- On January 31, 2000, Alaska Airlines Flight 261, an MD-83, crashed in the Pacific Ocean, due to loss of horizontal stabilizer control.[56] All 88 passengers and crew on board were killed. Following the crash, an improperly maintained Acme nut and jackscrew recovered from the aircraft were found to be excessively worn.[57] An airworthiness directive (AD) was issued by the FAA requiring more frequent inspections and lubrication of the jackscrew assembly.[58]

- On October 8, 2001, Scandinavian Airlines Flight 686, MD-87 SE-DMA collided with a small Cessna jet during take-off at Linate Airport, Milan, Italy. The Linate Airport disaster left 118 people dead. The cause of the accident was a misunderstanding between air traffic controllers and the Cessna jet, complicated by inoperative ground movement radar at the time of the accident. The SAS crew had no role in causing the accident.

- On May 7, 2002, China Northern Airlines Flight 6136, an MD-82, from Beijing to Dalian, crashed into Dalian Bay near Dalian after the pilot reported "fire on board". All 112 people on board were killed. Investigators determined that the fire had been set by a suicidal passenger.

- On November 30, 2004, Lion Air Flight 583, MD-82, crashed on landing at Adi Sumarmo Airport in Surakarta, Indonesia and overran the end of the runway, causing the death of 25 passengers and crew.

- On August 16, 2005, West Caribbean Airways Flight 708, MD-82, crashed in a mountainous region in northwest Venezuela killing all 152 passengers and eight crew.[59]

- On March 4, 2006, Lion Air Flight 8987, MD-82, after landing at Juanda International Airport, applied reverse thrust, although the reversers were stated to be out of order. This caused the aircraft to veer to the right and skid off the runway, coming to rest 7,000 ft (2,100 m) on the approach end of Runway 10. No one was killed, but the aircraft sustained $3 million in damage.[60]

- On March 16, 2007, a Kish Air MD-82, registration LZ-LDD leased from Bulgarian Air Charter was damaged beyond repair in a hard landing accident in Kish, Iran. There were no fatalities.

- On September 16, 2007, One-Two-GO Airlines Flight 269, MD-82, crashed at the side of the runway and exploded after an apparent attempt to execute a go-around in bad weather at Phuket International Airport in Phuket, Thailand. Of the 130 passengers and crew on board, 89 were killed.[61][62]

- On November 30, 2007, Atlasjet Flight 4203, MD-83, crashed in the southwestern province of Isparta, Turkey, killing all 57 passengers and seven crew.[63] The cause of the crash was attributed to pilot spatial disorientation.

- Between March 26 and March 27, 2008, and then again between April 8 and April 12, 2008, an FAA safety audit of American Airlines forced the airline to ground its entire fleet of MD-80 series aircraft (approximately 300) to inspect the aircraft's hydraulic wiring. American was forced to cancel nearly 2,500 flights in March and over 3,200 in April.[64] In addition, Delta Air Lines voluntarily inspected its own MD-80 fleet to ensure its 117 MD-80s were also operating within regulation. As a result, Delta cancelled 275 flights.[65]

- On August 20, 2008, Spanair Flight 5022, MD-82 registration EC-HFP, from Madrid's Barajas Airport crashed shortly after takeoff on a flight to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands. The MD-82 had 162 passengers and ten crew on board, of whom 18 survived. The crash was caused by attempting to take off with the flaps and slats retracted. The flight crew omitted the "set flaps and slats" item in both the After Start checklist and the Takeoff Imminent checklist.[66]

- On November 19, 2009, Compagnie Africaine d'Aviation Flight 3711, MD-82 9Q-CAB, overran the runway on landing at Goma International Airport, and suffered substantial damage. The overrun area was contaminated by solidified lava.[67]

- On June 21, 2010, Hewa Bora Airways Flight 601, MD-82 9Q-COQ, burst a tire on take-off from N'djili Airport, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Hydraulic systems and the port engine were damaged, and the nose gear did not lower when the aircraft returned to N'djili. All 110 people on board escaped uninjured. The airline blamed the state of the runway for the accident, but investigators found no fault with the runway.[68]

- On January 24, 2012, Swiftair Flight 94, MD-83 registration EC-JJS, suffered a wingtip strike while landing at Kandahar Airport, Afghanistan. Although there were no injuries to the 92 passengers and crew on board, the starboard wing sustained a broken main spar, and the aircraft was damaged beyond economic repair. It was consequently scrapped at Kandahar.[69]

- On June 3, 2012, Dana Air Flight 992, MD-83 registration 5N-RAM, crashed into a two-story building in Lagos, Nigeria, caused by engine failure. All 153 passengers and crew on board were killed, as well as 10 on the ground.[70][71][72]

- On July 24, 2014, Air Algérie Flight 5017, registration EC-LTV, a scheduled flight from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, to Algiers, Algeria, operated with an MD-83 leased from Swiftair. The aircraft crashed southeast of Gossi, Mali, about 50 minutes after takeoff. All 110 passengers and six crew were killed.[73]

- On March 5, 2015, Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 skidded off the runway on landing at LaGuardia Airport, New York in snowy weather. The MD-88, registration N909DL, was severely damaged. A few minor injuries occurred during evacuation via the emergency chutes.[74] Investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board were reportedly focusing on the aircraft's braking system and rudder.[34]

- On March 8, 2017 an Ameristar Jet Charter MD-83, registration N786TW, slid off the runway at Willow Run Airport in high winds during an aborted takeoff. The passengers, which included the Michigan Wolverines men's basketball team, exited through emergency doors onto wings and slides without injuries, but there was extensive damage to the aircraft.[75] The NTSB report said that the elevator had jammed, preventing flight, and although the pre-flight checklist had been followed, the checklist tested the operation of the elevator tabs but not the elevator itself.[76][77]

- On January 27, 2020 Caspian Airlines Flight 6936 an MD-83 overran the end of the Mahshahr Airport's runway 13 with 144 people on board. There were two injuries; the aircraft received substantial damage.[78]

Aircraft on display

- N259AA (cn 49289) – MD-82 on display at the Tulsa Air and Space Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.[79] The cabin has been converted into a movie theater to become the "MD-80 Discovery Center".[80][81]

- N290AA (cn 49302) – MD-82 is preserved at Tulsa Technology Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where it is used for aviation maintenance technician training.[82]

- N292AA (cn 49304) – MD-82 is on static display at the Carolina Children's Museum in Carolina, Puerto Rico.[83][84]

- N491AA (cn 49684) – MD-82 owned by Oklahoma State University and located at the Stillwater Regional Airport in Stillwater, Oklahoma.[85] It is used by the university's School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering as part of its education programs.[86]

- N948TW (cn 49575) is an MD-83 preserved by the Tristar Experience organization at Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport in Kansas City, Missouri. It is displayed as it appeared in service with Trans World Airlines in a special reversed-color "Wings of Pride" livery in the 1990s.[87][88]

- I-SMEL (cn 49247) – a former Meridiana MD-82 is displayed at the Volandia Park and Flight Museum in Milan.[89]

- B-2134 (cn 49518) is an SAIC-manufactured MD-82 preserved at Guangzhou Civil Aviation College in Guangzhou. It was previously operated by China Southern Airlines.

Specifications

| Variant | MD-81/82/83/88 | MD-87 |

|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | |

| 1-class seats[91] | 155Y @32-33" (max 172) | 130Y @31-33" (max 139) |

| 2-class seats[91] | 143: 12J @ 36" + 131Y@ 31-34" | 117: 12J+105Y |

| Length | 147 ft 10 in (45.06 m) | 130 ft 5 in (39.75 m) |

| Wing | 107 ft 8 in (32.82 m) span, 1,209 sq ft (112.3 m2) area | |

| Aspect ratio | 9.62[92] | |

| Tail height | 29 ft 7 in (9.02 m) | 30 ft 4 in (9.25 m) |

| Width | 131.6 in / 334.3 cm fuselage, 122.5 in / 311.2 cm cabin | |

| Cargo | 1,253 cu ft (35.5 m3) -83/88: 1,013 cu ft (28.7 m3) |

938 cu ft (26.6 m3) |

| Empty weight | 77,900–79,700 lb (35,300–36,200 kg) | 73,300 lb (33,200 kg) |

| MTOW | -81: 140,000 lb (63,500 kg) -82: 149,500 lb (67,800 kg) -83/88: 160,000 lb (72,600 kg) |

140,000–149,500 lb (63,500–67,800 kg) |

| Cruise speed | Long-range cruise: Mach 0.76[92][93] High-speed cruise:[92] Mach 0.8 (472 kn; 873 km/h)[91] | |

| Range[lower-alpha 1] | -81: 1,800 nmi (3,300 km) @ 137 pax -82: 2,050 nmi (3,800 km) @ 155 pax -83/88: 2,550 nmi (4,720 km) @ 155 pax |

2,400–2,900 nmi (4,400–5,400 km) |

| Takeoff[lower-alpha 2] | 7,200–8,000 ft (2,200–2,400 m) | 7,500 ft (2,300 m) |

| Fuel capacity | 5,850 US gal (22,100 L) -83/88: 7,000 US gal (26,000 L) | |

| Engines (×2) | Pratt & Whitney JT8D-200 series | |

| Thrust (×2) | 18,500–21,000 lbf (82–93 kN) | |

- ISA, 200nm alt + 45 mn LRC reserves

- MTOW, sea level, ISA

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Airbus A320

- Boeing 737-400

Related lists

References

- "McDonnell Douglas MD-80 Operators". www.planespotters.net.

- Norris, Guy and Wagner, Mark. Douglas Jetliners. MBI Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0676-1.

- "Orders & Deliveries". Boeing.

- "Boeing: History -- Chronology - 1977 - 1982". Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- "Historical Snapshot: MD-80/MD-90 COMMERCIAL TRANSPORTS". Boeing. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- Airclaims Jet Programs 1995

- Airliner Color History MD-80 & MD-90. ISBN 0-7603-0698-2

- "FAA Registry - Aircraft - Make / Model Inquiry". Registry.faa.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- Kraar, Louis (August 18, 1986). "Selling How One Man Landed China's $1 Billion Order: Gareth C.C. Chang of McDonnell Douglas spent six years of hope and frustration pursuing Peking's biggest U.S. purchase. He had to promise a lot more than planes". archive.fortune.com. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- YOSHIHARA, NANCY (13 April 1985). "Douglas, China Agree on Jet Co-Production: 1st Time Foreign Nation to Produce U.S. Jetliner" – via LA Times.

- "Boeing Delivers Last Ever MD-80 To TWA". MediaRoom.

- Norris, Guy (May 11, 2008). "New-Generation GE Open Rotor and Regional Jet Engine Demo Efforts Planned". archive.li. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Conway, Peter (October 5, 2012). "Converted MD-80 lifts off on maiden flight". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David (October 20, 2015). "EASA approves US firm's MD-80 freighter conversion". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- Polek, Gregory (February 18, 2013). "First MD-80 Freighter Set To Fly in U.S." Aviation International News. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- "Commercial Jet : Advanced MRO Solutions : News". commercialjet.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- "McDonnell Douglas MD-80 Production List - Planespotters.net Just Aviation". Planespotters.net. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "American to say adios to MD-80s in 2019". Flight Global. 31 October 2017.

- "MRO | Aviation Week Network". aviationweek.com.

- "American Airlines Announces Schedule of Final MD-80 Revenue Flights". American Airlines. 24 June 2019.

- Aerospace Notebook: MD-80 era winding down as fuel costs rise, Seattlepi.com, June 24, 2008.

- "Midwest Airlines will cut 1,200 jobs". Kansas City Business Journal. July 14, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "JT8D-219Turbofan Engine" (PDF). Pratt & Whitney. September 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- "Commercial Aircraft of the World". Flight International, October 17, 1981.

- Flight International Commercial Aircraft of the World October 23, 1982

- "Commercial Aircraft of the World". Flight International, October 15, 1983.

- Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1994–1995.

- Jane's All the World's Aircraft 2004-2005

- Taylor 1982, p. 419.

- "红色巨灵神 中国大型运输机之路八 运十三篇". cqvip.com.

- "红色巨灵神——中国大型运输机之路(八)运13(二)-【维普网】-仓储式在线作品出版平台-www.cqvip.com". 2010.cqvip.com. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "Airliner List". airlinerlist.com.

- McMenemy, Jeff (June 6, 2020). "Dover High grad pilots last flight of Delta's 'Mad Dog'". Foster's Daily Democrat. Dover, New Hampshire. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Pasztor, Andy (March 9, 2015). "Delta Crash: Investigators Suspect Possible Brake Problems". The Wall Street Journal. p. A3. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- "Commercial aircraft of the world" (PDF). Flight International. October 12, 1985. p. 61.

- Morris, John; Romberg, Lars (1984). "Technology and the market place-A changing air transport equation". SAE Transactions. SAE International. 93 (841545): 6.447–6.458. JSTOR 44467158.

- Moll, Nigel (December 1986). "GA strong at Farnborough". Minifeature. Flying. Vol. 113 no. 12. pp. 96–97. ISSN 0015-4806.

- "Farnborough finds industry on edge of many decisions". Air Transport World. Vol. 23. October 1986. pp. 18+.

- "MDC studies propfan ASW" (PDF). Flight International. August 22, 1987. p. 8.

- "PlaneSpotters.net". June 2020.

- Warwick, Graham. "Let's Go Fight Fires - In an MD-87". aviationweek.com. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "20 large air tankers to be on exclusive use contracts this year - Fire Aviation". Fire Aviation. 10 March 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "American Airlines retires classic MD-80 planes". CNN. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "By the numbers: A final salute to Delta's MD-88 and MD-90 'Mad Dogs'". Delta News Hub (Press release). 2020-06-01.

- "Boeing: Commercial". Active.boeing.com. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80 incidents. Aviation-Safety.net, September 28, 2015.

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80 Accidents. Aviation-Safety.net, September 28, 2015.

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80 Accident Statistics. Aviation-Safety.net, September 28, 2015.

- "Accident: Dana MD83 at Port Harcourt on Feb 20th 2018, runway excursion". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-81 (MD-81) YU-ANA Mont San-Pietro". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- Ray, Sally J. (1999). Strategic Communication in Crisis Management: Lessons from the Airline Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9781567201536.

On the ground two persons were killed, one person seriously injured, and four persons suffered minor injuries

- "National Transportation Safety Board Aircraft Accident Report Northwest Airlines, Inc. McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82, N312RC Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport Romulus, Michigan August 16, 1987" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. May 10, 1988. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Wilkerson, Isabel (1987-08-22). "Crash Survivor's Psychic Pain May Be the Hardest to Heal". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-81 (MD-81) N1003G Posadas Airport, MI (PSS)". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (MD-82) B-2141 Urumqi Airport (URC)". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ""Aircraft Accident Report Loss of Control and Impact with Pacific Ocean Alaska Airlines Flight 261 McDonnell Douglas MD-83, N963AS About 2.7 Miles North of Anacapa Island, California January 31, 2000"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2007.

- "NTSB photo of worn jackscrew". NTSB. NTSB. 2000-01-31. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- "Airworthiness Directives; McDonnell Douglas Model DC-9, Model MD-90-30, Model 717-200, and Model MD-88 Airplanes" Archived 18 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "CNN.com - 160 believed dead in Venezuela jet crash - Aug 16, 2005". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- Harro Ranter (4 March 2006). "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (MD-82) PK-LMW Surabaya-Juanda Airport (SUB)". aviation-safety.net.

- "Asia-Pacific | Search for clues after Thai crash". BBC News. 2007-09-17. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "Survivors recount Thai jet crash". CNN.com. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- "56 feared dead in Turkey jet crash". CNN. November 30, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "Cancellation wave latest problem for airlines". NBC News, April 10, 2008.

- "American, Delta cancel more flights to inspect MD-80 aircraft". archive.li. March 27, 2008. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Report A-032/2008 Accident Involving a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (MD-82) aircraft, registration EC-HFP, operated by Spanair, at Madrid-Barajas Airport, on 20 August 2008" (PDF). Comisión de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación Civil. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- Hradecky, Simon (21 June 2010). "Accident: Hewa Bora MD82 at Kinshasa on Jun 21st 2010, burst tyre on takeoff, hydraulic failure, runway excursion on landing". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Hradecky, Simon (20 March 2012). "Accident: Swiftair MD83 at Kandahar on Jan 24th 2012, wing tip strike". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- "Official: 153 on plane, at least 10 on ground dead after Nigeria crash". CNN. 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ""Bereaved walk among dead after Nigeria plane crash"". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012.

- "Dana Air 5N-RAM (McDonnell Douglas MD-80/90 – MSN 53019) (Ex N944AS )". Airfleets.net. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- "Algeria airliner feared crashed on flight from Burkina Faso". BBC News. July 24, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Hradecky, Simon. "Accident: Delta MD88 at New York on Mar 5th 2015, runway excursion on landing". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Lage, Larry (March 8, 2017). "Michigan team plane slides off runway, players safe". Yahoo! News Associated Press. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Thompson, Chris. "NTSB Report: Michigan's 2017 Plane Accident Was A Couple Split-Second Decisions Away From Catastrophe". Deadspin. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- "Runway Overrun During Rejected Takeoff Ameristar Air Cargo, Inc., dba Ameristar Charters, flight 9363 Boeing MD-83, N786TW Ypsilanti, Michigan March 8, 2017 Accident Report" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- "Caspian MD83 at Mahshahr on Jan 27th 2020, overran runway on landing". Aviation Herald. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "N259AA American Airlines McDonnell Douglas MD-82 - cn 49289 / 1193". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "MD-80 Discovery Center". Tulsa Air and Space Museum & Planetarium. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Discovery Center Launched At Tulsa Air And Space Museum". Times Record. GateHouse Media, LLC. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Tulsa Technology Center

- "Avión". Museo del Nino (in Spanish). Museo del Niño de Carolina. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "N292AA American Airlines McDonnell Douglas MD-82 - cn 49304 / 1223". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "N491AA American Airlines McDonnell Douglas MD-82 - cn 49684 / 1564". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "American Airlines delivers retired MD-80 to OSU for hands-on learning, STEM study". News and Information. Oklahoma State University. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "MD83 – TriStar Experience". www.tristarexperience.org.

- "Wings of Pride: A TWA Plane that was Nearly Forgotten". August 7, 2015.

- "McDonnell Douglas MD-82 (I-SMEL) Aircraft Pictures & Photos - AirTeamImages.com". www.airteamimages.com.

- "MD-80 Series Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). McDonnell Douglas. Dec 1989.

- "MD-80" (PDF). Boeing. Aug 31, 2007.

- McDonnell Douglas Corporation (January 1981). "The McDonnell Douglas DC-9 Super 80 Configuration Guide". p. I–7.

- "Commercial aircraft" (PDF). Flight International. 31 October – 6 November 2000. p. 68.

Sources

- Becher, Thomas. Douglas Twinjets, DC-9, MD-80, MD-90 and Boeing 717. The Crowood Press, 2002. ISBN 1-86126-446-1.

- Michell, Simon. Jane's Civil and Military Aircraft Upgrades 1994–95 Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group, 1994. ISBN 0-7106-1208-7.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1982–83. London: Jane's Yearbooks, 1982. ISBN 0-7106-0748-2.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1988–89. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Defence Data, 1988. ISBN 0-7106-0867-5.

- Thisdell, Dan and Fafard, Antoine. "World Airliner Census". Flight International, Volume 190, No. 5550, 9–15 August 2016. pp. 20–43. ISSN 0015-3710