Spatial disorientation

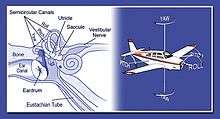

Spatial disorientation of an aviator is the inability to determine angle, altitude or speed. It is most critical at night or in poor weather, when there is no visible horizon, since vision is the dominant sense for orientation. Auditory systems and the vestibular (inner ear) system for co-ordinating movement with balance can also create illusory nonvisual sensations, as can other sensory receptors located in the skin, muscles, tendons and joints.

Senses during flight

There are four physiologic systems that interact to allow humans to orient themselves in space. Vision is the dominant sense for orientation, but the vestibular system, proprioceptive system and auditory system also play a role. During the abnormal acceleratory environment of flight, the vestibular and proprioceptive systems do not respond truthfully. Because of inertial forces created by acceleration of the aircraft along with centrifugal force caused by turning, the net gravitoinertial force sensed primarily by the otolith organs is not aligned with gravity, leading to perceptual misjudgment of the vertical. In addition, the inner ear contains rotational accelerometers, known as the semicircular canals, which provide information to the lower brain on rotational accelerations in the pitch, roll and yaw axes. However, prolonged rotation (beyond 15–20 s) results in a cessation of semicircular output, and cessation of rotation thereafter can even result in the perception of motion in the opposite direction. Under ideal visual conditions the above illusions are unlikely to be perceived, but at night or in poor weather the visual inputs are no longer capable of overriding these illusory nonvisual sensations. In many cases, illusory visual inputs such as a sloping cloud deck can also lead to misjudgments of the vertical and of speed and distance or even combine with the nonvisual ones to produce an even more powerful illusion. The result of these various visual and nonvisual illusions is spatial disorientation.[1][2][3] Various models have been developed to yield quantitative predictions of disorientation associated with known aircraft accelerations.[4]

Effects of disorientation

Once an aircraft enters conditions under which the pilot cannot see a distinct visual horizon, the drift in the inner ear continues uncorrected. Errors in the perceived rate of turn about any axis can build up at a rate of 0.2 to 0.3 degrees per second. If the pilot is not proficient in the use of gyroscopic flight instruments, these errors will build up to a point that control of the aircraft is lost, usually in a steep, diving turn known as a graveyard spiral. During the entire time, leading up to and well into the maneuver, the pilot remains unaware of the turning, believing that the aircraft is maintaining straight flight. One of the most famous mishaps in aviation history involving the graveyard spiral is the crash involving John F. Kennedy Jr. in 1999.[5]

The graveyard spiral usually terminates when the g-forces on the aircraft build up to and exceed the structural strength of the airframe, resulting in catastrophic failure, or when the aircraft contacts the ground. In a 1954 study (180 – Degree Turn Experiment), the University of Illinois Institute of Aviation[6] found that 19 out of 20 non-instrument-rated subject pilots went into a graveyard spiral soon after entering simulated instrument conditions. The 20th pilot also lost control of his aircraft, but in another maneuver. The average time between onset of instrument conditions and loss of control was 178 seconds.

Spatial disorientation can also affect instrument-rated pilots in certain conditions. A powerful tumbling sensation (vertigo) can be set up if the pilot moves his or her head too much during instrument flight. This is called the Coriolis illusion. Pilots are also susceptible to spatial disorientation during night flight over featureless terrain.

Spatial orientation

Spatial orientation (the inverse being spatial disorientation, aka spatial-D) is the ability to maintain body orientation and posture in relation to the surrounding environment (physical space) at rest and during motion. Humans have evolved to maintain spatial orientation on the ground. The three-dimensional environment of flight is unfamiliar to the human body, creating sensory conflicts and illusions that make spatial orientation difficult and sometimes impossible to achieve. Statistics show that between 5% and 10% of all general aviation accidents can be attributed to spatial disorientation, 90% of which are fatal.

Good spatial orientation on the ground relies on the use of visual, vestibular (organs of equilibrium located in the inner ear), and proprioceptive (receptors located in the skin, muscles, tendons, and joints) sensory information. Changes in linear acceleration, angular acceleration, and gravity are detected by the vestibular system and the proprioceptive receptors, and then compared in the brain with visual information.

Spatial-D and G-induced loss of consciousness (GLOC) are two of the most common causes of death from human factors in military aviation.[7] Spatial orientation in flight is difficult to achieve because numerous sensory stimuli (visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive) vary in magnitude, direction, and frequency. Any differences or discrepancies between visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensory inputs result in a sensory mismatch that can produce illusions and lead to spatial disorientation.

The otolith organs and orientation

Two otolith organs, the saccule and utricle, are located in each ear and are set at right angles to each other. The utricle detects changes in linear acceleration in the horizontal plane, while the saccule detects gravity changes in the vertical plane. However, the inertial forces resulting from linear accelerations cannot be distinguished from the force of gravity (according to the equivalence principle of general relativity they are the same thing) therefore, gravity can also produce stimulation of the utricle and saccule. A response of this type will occur during a vertical take-off in a helicopter or following the sudden opening of a parachute after a free fall.

Non-visible horizon

Anyone in an aircraft that is making a coordinated turn, no matter how steep, will have little or no sensation of being tilted in the air unless the horizon is visible. Similarly, it is possible to gradually climb or descend without a noticeable change in pressure against the seat. In some aircraft, it is possible to execute a loop without pulling negative g-forces so that, without visual reference, the pilot could be upside down without being aware of it. This is because a gradual change in any direction of movement may not be strong enough to activate the fluid in the vestibular system, so the pilot may not realize that the aircraft is accelerating, decelerating, or banking.

In the media

- It is believed that singer Jim Reeves was suffering from spatial disorientation when his Beechcraft aircraft crashed in the Brentwood area of Nashville, Tennessee, during a violent thunderstorm on 31 July 1964, claiming the lives of both Reeves and his pianist Dean Manuel. The same was also believed of the pilots in the crashes of singers Buddy Holly (The Day the Music Died) and Patsy Cline.

- This phenomenon was extensively reported in the press in 1999, after John F. Kennedy, Jr.'s plane went down during a night flight over water near Martha's Vineyard. Subsequent investigation pointed to spatial disorientation as a probable cause of the accident.

Examples

- 1963 Camden PA-24 crash – Patsy Cline plane crash

- Adam Air Flight 574 – January 1, 2007

- Aeroflot Flight 821 – September 14, 2008

- Afriqiyah Airways Flight 771 – May 12, 2010

- Agni Air Flight 101 – August 24, 2010

- Air France Flight 447 – June 1, 2009

- Air India Flight 855 – January 1, 1978

- Atlasjet Flight 4203 – November 30, 2007

- Copa Airlines Flight 201 - June 6, 1992

- Crossair Flight 498 - January 10, 2000

- John F. Kennedy Jr. plane crash – July 16, 1999[5]

- The Day the Music Died – February 3, 1959

- Disappearance of Frederick Valentich – October 21, 1978

- Flash Airlines Flight 604 – January 3, 2004 (controversial)

- Gulf Air Flight 072 – August 23, 2000

- 2005 Loganair Islander accident – March 15, 2005

- Kenya Airways Flight 507 – May 5, 2007

- Loss of the Riama — October 1, 2012

- Japanese F-35A accident - April 10, 2019[8]

See also

- Balance disorder

- Bárány chair – A device used for aerospace physiology training

- Broken escalator phenomenon – The sensation of losing balance or dizziness when stepping onto an escalator which is not working

- Brownout (aeronautics)

- Dizziness

- Equilibrioception – Physiological sense allowing animals to dynamically maintain an unstable posture

- Ideomotor phenomenon – A psychological phenomenon wherein a subject makes motions unconsciously

- Illusions of self-motion

- Motion sickness – Nausea caused by motion

- Pilot error – Decision, action or inaction by a pilot of an aircraft

- Proprioception – Sense of the relative position of one's own body parts and strength of effort employed in movement

- Sense of direction

- Sensory illusions in aviation

- Situation awareness – Adequate perception of environmental elements and external events

- Spatial ability

- Topographical disorientation

References

- Previc, F. H., & Ercoline, W. R. (2004). Spatial disorientation in aviation. Reston, VA: American Institute of Astronautics and Aeronautics.

- "GO FLIGHT MEDICINE - Spatial Disorientation". April 1, 2013.

- "spatial disorientation - physiology". Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Newman, M. C., Lawson, B. D., Rupert, A. H., & McGrath, B. J. (2011, August). The role of perceptual modeling in the understanding of spatial disorientation during flight and ground-based simulator training. In AIAA modeling and simulation technologies conference and exhibit, AIAA (Vol. 5009).

- "GO FLIGHT MEDICINE - JFK Jr Piper Saratoga Mishap". April 15, 2014.

- Aulls Bryan, Leslie (1954). 180-degree turn experiment. University of Illinois. ASIN B0007EXGMI. LCCN a54009717. OCLC 4736008. OL 207786M.

- "Spatial Disorientation - Go Flight Medicine". 1 April 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- "Japan pilot crashed after 'spatial disorientation'". 2019-06-10. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

External links

- "Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory – Brandeis University". Retrieved 30 July 2016.