Northeast Coast Campaign (1756)

The Northeast Coast Campaign (1756) occurred during the French and Indian War, in which the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia raided the British communities along the former border of New England and Acadia in present-day Maine.[1]

Historical context

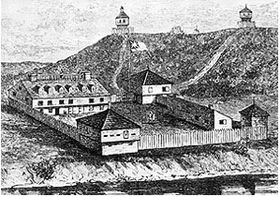

In response to Gorham's raid on the St. John River in 1748, the Governor of Canada threatened to support native raids along the northern New England border.[2] There were many previous raids from the Mi'kmaq militia and Maliseet Militias against British settlers on the border (1703, 1723, 1724, 1745, 1746, 1747). During the war, along the former border of Acadia, the Kennebec River, the British built Fort Halifax (Winslow), Fort Shirley (Dresden, formerly Frankfurt) and Fort Western (Augusta).[3][4]

Fort Halifax was completed on 4 September 1754 and the raids on the fort began on 6 November.[5] Wabanaki killed and scalped one soldier and took four others captive.[6] In response, Governor Shirley sent 100 more troops to the fort. The following year, the natives conducted the Northeast Coast Campaign (1755) and then began the 1756 Campaign in the spring.

Campaign

Williamson reports that the natives had killed hundreds of British settlers in the Campaign.[7] On 24 March the natives raided present-day Cushing, killing two men and scalping a third who survived. Then they captured a man at North-Yarmouth and killed another man and captured a woman at Flying Point.[8] On 3 May they ambushed three men and managed to take one prisoner to Canada (who eventually made his way to Halifax, where he died of smallpox). On 14 May about 20 natives led by Chief Poland ambushed another two men, killing one and scalping another who survived. At Georgetown, natives killed two parents and took their three children captive,[7] The natives attacked the fort without success, however, they killed all the cattle on the Island.[7]

Four natives attacked and killed two soldiers at Fort Halifax.[7] They also plundered fishing vessels, killing their crew. On 26 September they burned a schooner at St. Georges, killing three men while three others went missing. On October 14, the natives attacked Captain Rouse’s ship, killing ten of his crew.[7]

As a result of the Campaign, numerous British settlers abandoned their farms and property. There were 260 soldiers at the garrisons who were divided into five ranging parties. The British had two vessels protecting the eastern seaboard.[9]

Aftermath

There was another campaign in 1757 and 1758. In 1757, the Anasunticooks fired on Captain Lithgow and a party of eight at Topsham. They wounded two of the soldiers and killed two others. Two natives were killed in the skirmish.[7] They then attacked a blockhouse at Pleasant Point, killing one[10] and, on 1 June, began the siege of a dwelling on Island Matinicus, where a family defended themselves and their five children and son-in-law for ten days. The father was killed, the rest taken into captivity and the house destroyed.[10]

On 13 August 1758, Boishebert left Miramichi, New Brunswick with 400 soldiers, including Acadians whom he led from Port Toulouse. They marched to Fort St George (Thomaston) and then Fort Western (present-day Augusta) and laid waste to farms but were unsuccessfully in taking the forts, and raided Munduncook (Friendship) where they wounded eight British settlers and killed others.[11][12][13][14][15]

References

- Scott, Tod (2016). "Mi'kmaw Armed Resistance to British Expansion in Northern New England (1676–1761)". Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. 19: 1–18.

- https://archive.org/stream/selectionsfrompu00nova#page/n205/mode/1up

- Attacks on these forts continued through Father Le Loutre's War (See Maine Historical Society).

- Charles Morris had intelligence from Acadians that another Northeast Coast Campaign was planned for 1755 (See Charles Morris

- Williamson, William D. (1832). The History of the State of Maine: From Its First Discovery, 1602, to the Separation, A. D. 1820, Inclusive. Vol. II. Hallowell, Maine: Glazier, Masters & Company. p. 300.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williamson (1832), p. 302; (see shirley’s letters oct 30, p. 102.

- Williamson (1832), p. 323.

- Williamson (1832), p. 320.

- Williamson (1832), p. 325.

- Williamson (1832), p. 326.

- Leblanc, Phyllis E. (1979). "Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot, Charles". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Eaton, Cyrus (1865). History of Thomaston, Rockland, and South Thomaston, Maine, from their First Exploration, 1605; with Family Genealogies. Hallowell, Maine: Masters, Smith & Co. p. 77.

- Williamson (1832), p. 459.

- Continuation of the history of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, p. 41

- General Moncton in Halifax – he says Maliseet there as well to attack St. Georges (Williamson 1832, p. 333) 2 Minot p. 41

- Brodhead, John Romeyn (1858). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Vol. 10. Albany: Weed, Parsons and Co. p. 426. – 1756 Campaign