Loquat

The loquat — Eriobotrya japonica — is a large evergreen shrub or tree, grown commercially for its orange fruit, its leaves for tea (known as "biwa cha" in Japan), and also cultivated as an ornamental plant.

| Loquat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Loquat leaves and fruits | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Eriobotrya |

| Species: | E. japonica |

| Binomial name | |

| Eriobotrya japonica | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

| Loquat | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 蘆橘 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 芦橘 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Modern Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 枇杷 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The loquat is in the family Rosaceae, and is native to the cooler hill regions of south-central China.[2][3] Since it reached its shores, the loquat has been grown in Japan for over 1,000 years, and has been introduced to regions with subtropical to mild temperate climates throughout the world.[4][5]

Eriobotrya japonica was formerly thought to be closely related to the genus Mespilus, and is still sometimes known as the Japanese medlar. It is also known as Japanese plum[6] and Chinese plum,[7] as well as pipa in China, and nespolo in southern Italy (in the north that name is used for Mespilus germanicus).

Description

Loquat is a large evergreen shrub or small tree, with a rounded crown, short trunk and woolly new twigs. The tree can grow to 5–10 metres (16–33 ft) tall, but is often smaller, about 3–4 metres (10–13 ft). The fruit begins to ripen during spring to summer depending on the temperature in the area. The leaves are alternate, simple, 10–25 centimetres (4–10 in) long, dark green, tough and leathery in texture, with a serrated margin, and densely velvety-hairy below with thick yellow-brown pubescence; the young leaves are also densely pubescent above, but this soon rubs off.[8][9][10][11]

Fruit

Loquats are unusual among fruit trees in that the flowers appear in the autumn or early winter, and the fruits are ripe at any time from early spring to early summer.[12] The flowers are 2 cm (1 in) in diameter, white, with five petals, and produced in stiff panicles of three to ten flowers. The flowers have a sweet, heady aroma that can be smelled from a distance.

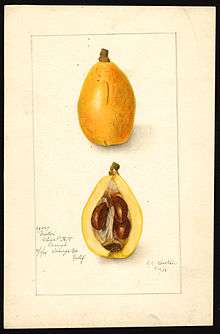

Loquat fruits, growing in clusters, are oval, rounded or pear-shaped, 3–5 centimetres (1–2 in) long, with a smooth or downy, yellow or orange, sometimes red-blushed skin. The succulent, tangy flesh is white, yellow or orange and sweet to subacid or acid, depending on the cultivar.

Each fruit contains from one to ten ovules, with three to five being most common.[13] A variable number of the ovules mature into large brown seeds (with different numbers of seeds appearing in each fruit on the same tree, usually between one and four).

The fruits are the sweetest when soft and orange. The flavour is a mixture of peach, citrus and mild mango.

History and taxonomy

The loquat is originally from China, where related species can be found growing in the wild.[14][15][16][17]. It has been cultivated there for over 1,000 years. It has also become naturalised in Georgia, Armenia, Afghanistan, Australia, Azerbaijan, Bermuda, Chile, Kenya, India, Iran, Iraq, South Africa, the whole Mediterranean Basin, Pakistan, New Zealand, Réunion, Tonga, Central America, Mexico, South America and in warmer parts of the United States (Hawaii, California, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina). In Louisiana, many refer to loquats as "misbeliefs" and they grow in yards of homes.[18] Chinese immigrants are presumed to have carried the loquat to Hawaii and California.[19][20] It has been cultivated in Japan for about 1,000 years and presumably the fruits and seeds were brought back from China to Japan by the many Japanese scholars visiting and studying in China during the Tang Dynasty.

The loquat was often mentioned in medieval Chinese literature, such as the poems of Li Bai. Its original name is no longer used in most Chinese dialects, and has been replaced by pipa (枇杷), which is a reference to the fruit's visual resemblance to a miniature pipa lute.

The first European record of the species might have been in the 16th century by Michał Boym Polish jesuit, orientalist, politician and missionary to China. He described loquat in his Flora sinensis, the first European natural history book about China.[21] The common name for the fruit is from portuguese nêspera (from the modified nespilus, originally mespilus, which referred to the medlar), (José Pedro Machado, Dicionário Etimológico da Língua Portuguesa, 1967). Since the first contact of the Portuguese with the Japanese and Chinese dates also from the sixteenth century, it is possible that some were brought back to Europe, as was probably the case with other species like the hachiya persimmon variety.

Eriobotrya japonica was again described in Europe by Carl Peter Thunberg, as Mespilus japonica in 1780, and was relocated to the genus Eriobotrya (from Greek εριο "wool" and βοτρυών "cluster") by John Lindley, who published these changes in 1821.

The most common variety in Portugal is the late ripening Tanaka, where it is popular in gardens and backyards, but not commercially produced. In northern Portugal it is also popularly called magnório/magnólio, probably something to do with the French botanist Pierre Magnol. In Spain, the fruits are similarly called "nísperos" and are commercially exploited, Spain being the largest producer worldwide, after China, with 41,487t annually, half of which is destined to export markets.

Cultivation

Over 800 loquat cultivars exist in Asia. Self-fertile variants include the 'Gold Nugget' and 'Mogi' cultivars.[4] The loquat is easy to grow in subtropical to mild temperate climates where it is often primarily grown as an ornamental plant, especially for its sweet-scented flowers, and secondarily for its delicious fruit. The boldly textured foliage adds a tropical look to gardens, contrasting well with many other plants.

There are many named cultivars, with orange or white flesh.[22] Some cultivars are intended for home-growing, where the flowers open gradually, and thus the fruit also ripens gradually, compared to the commercially grown species where the flowers open almost simultaneously, and the whole tree's fruit also ripens together.

Japan is the leading producer of loquats followed by Israel and then Brazil.[22] In Europe, Spain is the main producer of loquat.[23]

In temperate climates it is grown as an ornamental with winter protection, as the fruits seldom ripen to an edible state. In the United Kingdom, it has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[24][25]

In the US, the loquat tree is hardy only in USDA zones 8 and above, and will flower only where winter temperatures do not fall below 30 °F (−1 °C). In such areas, the tree flowers in autumn and the fruit ripens in late winter.[4] It is popular in the East, as well as the South.

Culinary use

The loquat has a high sugar, acid and pectin content.[26] It is eaten as a fresh fruit and mixes well with other fruits in fresh fruit salads or fruit cups. The fruits are also commonly used to make jam, jelly and chutney, and are often served poached in light syrup. Firm, slightly immature fruits are best for making pies or tarts.

The fruit is sometimes canned or processed into confections. The waste ratio is 30 percent or more, due to the seed size.

Alcoholic beverages

Loquats can also be used to make light wine. They are fermented into a fruit wine, sometimes using just crystal sugar and white liquor.

In Italy nespolino[27] liqueur is made from the seeds, reminiscent of nocino and amaretto, both prepared from nuts and apricot kernels. Both the loquat seeds and the apricot kernels contain cyanogenic glycosides, but the drinks are prepared from varieties that contain only small quantities (such as Mogi and Tanaka[28]), so there is no risk of cyanide poisoning.

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 197 kJ (47 kcal) |

12.14 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 1.7 g |

0.2 g | |

0.43 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 10% 76 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 2% 0.019 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.024 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 1% 0.18 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 8% 0.1 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 4% 14 μg |

| Vitamin C | 1% 1 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 2% 16 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.28 mg |

| Magnesium | 4% 13 mg |

| Manganese | 7% 0.148 mg |

| Phosphorus | 4% 27 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 266 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.05 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

The loquat is low in sodium and high in vitamin A, vitamin B6, dietary fiber, potassium, and manganese.[29]

Like most related plants, the seeds (pips) and young leaves of the plant are slightly poisonous, containing small amounts of cyanogenic glycosides (including amygdalin) which release cyanide when digested, though the low concentration and bitter flavour normally prevent enough being eaten to cause harm.

Etymology

The name loquat derives from lou4 gwat1, the Cantonese pronunciation of the classical Chinese: 蘆橘; pinyin: lújú, literally "black orange". The phrase "black orange" originally actually referred to unripened kumquats, which are dark green in color. But the name was mistakenly applied to the loquat we know today by the ancient Chinese poet Su Shi when he was residing in southern China, and the mistake was widely taken up by the Cantonese region thereafter.

Symbolism

In China, the loquat is known as the 'pipa' (枇杷) and because of its golden colour, represents gold and wealth. It is often one in a bowl or composite of fruits and vegetables (such as spring onions, artemisia leaves, pomegranates, kumquats, etc.) to represent auspicious wishes or the 'Five Prosperities' or wurui (五瑞).[30]

See also

- Kumquat – although kumquats are not related botanically to loquats, the two names share an origin in their old Chinese names

- Coppertone loquat, a hybrid of Eriobotrya deflexa (synonym: Photinia deflexa) and Rhaphiolepis indica

References

- "The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species". Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Loquat Fact Sheet". UC Davis College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences.

- "Flora of China". efloras.org.

- Staub, Jack (2008). 75 Remarkable Fruits For Your Garden. Gibbs Smith. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-4236-0881-3.

- "Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl". gbif.org. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Japanese Plum / Loquat". University of Florida, Nassau County Extension, Horticulture. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- Hunt, Linda M.; Arar, Nedal Hamdi; Akana. Laurie L. (2000). "Herbs, Prayer, and Insulin Use of Medical and Alternative Treatments by a Group of Mexican American Diabetes Patients". The Journal of Family Practice. 49 (3). Archived from the original on 2013-06-29.

- Lindley, John (1821). "Eriobotrya japonica". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 13 (1): 102.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter. (1780). Nova Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis 3: 208, Mespilus japonica

- Ascherson, Paul Friedrich August & Schweinfurth, Georg August. (1887). Illustration de la Flore d'Égypte 73, Photinia japonica

- Davidse, G., M. Sousa Sánchez, S. Knapp & F. Chiang Cabrera. (2014). Saururaceae a Zygophyllaceae. 2(3): ined. In G. Davidse, M. Sousa Sánchez, S. Knapp & F. Chiang Cabrera (eds.) Flora Mesoamericana. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México D.F..

- "LOQUAT Fruit Facts". California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Loquat". Hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- "Loquat, production and market" (PDF). First international symposium on loquat. Zaragoza : CIHEAM Options Méditerranéennes.

- Lin, S., Sharpe, R. H., and Janick, J. (1999). "Loquat: Botany and Horticulture" (PDF). Horticultural Reviews. 23: 235–236.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Li, G. F., Zhang, Z. K., and Lin, S. Q. "Origin and Evolution of Eriobotrya". ISHS Acta Horticulturae 887: III International Symposium on Loquat.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Zhang, H. Z., Peng, S. A., Cai, L. H., and Fang, D. Q. (1990). "The germplasm resources of the genus Eriobotrya with special reference on the origin of E. japonica Lindl". 17 (1 ed.). Acta Horticulturae Sinica: 5–12. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2015-04-19. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bir, Sara, 1976– (2018). The fruit forager's companion : ferments, desserts, main dishes, and more from your neighborhood and beyond. White River Junction, Vermont. ISBN 9781603587167. OCLC 1005602236.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Biota of North America Project, Eriobotrya japonica. bonap.net (2014)

- loquat, Eriobotrya japonica. Weeds of Australia, Queensland Biosecurity Edition

- Flora Chin. W: Edward Kajdański: Michał Boym: ambasador Państwa Środka. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1999, s. 183. ISBN 978-83-05-13096-7.(pol.)

- "LOQUAT Fruit Facts". Crfg.org. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- "Agroalimentación. El cultivo del Níspero". canales.hoy.es. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- "RHS Plant Selector Eriobotrya japonica (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "AGM Plants – Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 36. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- California Rare Fruit Growers (1997). "Loquat". Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- "World News – Eriobotrya_japonica". Cosplaxy.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Siddiq, Muhammad (2012). Tropical and Subtropical Fruits: Postharvest Physiology, Processing and Packaging. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1140–. ISBN 978-1-118-32411-0.

- "Wolfram-Alpha: Making the world's knowledge computable". Wolframalpha.com. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- Welch, Patricia Bjaaland. Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery. Singapore: Tuttle, 2008, pp. 54-55.

External links

| Look up loquat in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Loquat — Eriobotrya japonica. |

- Botanical and Horticultural Information on the Loquat (Traditional Chinese).

- Badenes M.L., Canyamas T., Llácer G., Martínez J., Romero C. & Soriano J.M. (2003) Genetic diversity in european collection of loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.). Acta horticulturae 620:169–174.

- Loquat Fruit Facts from the California Rare Fruit Growers

- Purdue University Center for New Crops & Plant Products Loquat webpage

- Loquat Growing in the Florida Home Landscape, from the University of Florida IFAS Extension Website

- http://alienplantsbelgium.be/content/eriobotrya-japonica