List of Egyptian mummies (royalty)

The following is a list of mummies that include Egyptian Pharaohs and their named mummified family members.[lower-alpha 1] Some of these mummies have been found to be remarkably intact, while others have been damaged from tomb robbers and environmental conditions. Given the technology/wealth at the time, all known predynastic rulers were buried in open tombs. It was not until Pharaoh Den of the first dynasty that things such as a staircase and architectural elements were added which provided better protection from the elements.[1]

Identified

| Name | Alias | Year of Death | Dynasty | gender | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahhotep II | N/A | Unknown | 17th | Female | 1858 |  |

The mummy of Ahhotep II was destroyed in 1859.[2] |

| Ahmose (princess) | N/A | Unknown | 17th | Female | 1903-1905 | Princess Ahmose was buried in tomb QV47 in the Valley of the Queens.[3] Her mummy was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli during his excavations from 1903-1905.[4] | |

| Ahmose I | Amasis | 1525 BC | 18th | Male | 1881 |  |

Ahmose I's mummy was discovered in 1881 within the Deir el-Bahri Cache. His name was later found written in hieroglyphs when the mummy was unwrapped. The body bore signs of having been plundered by ancient grave-robbers, his head having been broken off from his body and his nose smashed.[5] |

| Ahmose-Henutemipet | N/A | Unknown | 17th/18th | Female | 1881 | Ahmose-Henutemipet was found in 1881 entombed in DB320. Her remains were found badly damaged, likely by tomb robbers. | |

| Ahmose-Henuttamehu | N/A | Unknown | 17th/18th | Female | 1881 | Ahmose-Henuttamehu was found in 1881 entombed in DB320. Like Ahmose-Henutemipet, she was found to be an old woman when she died as her teeth are worn. | |

| Ahmose-Meritamon | Meryetamun | Unknown | 17th | Female | Unknown |  |

Ahmose-Meritamon was found entombed in DB320. Like other mummies of the era, she was found to be heavily damaged by tomb robbers. An examination of her mummy shows that she suffered a head wound prior to her death which was the possible result of falling backwards.[6] |

| Ahmose-Meritamun | Ahmose-Meritamon | Unknown | 18th | Female | 1930 |  |

Her mummy was found carefully rewrapped, which was determined to have occurred during the reign of Pinedjem I. |

| Ahmose Inhapy | Ahmose-Inhapi | Unknown | 17th/18th | Female | 1881 | The mummy was found in the outer coffin of Lady Rai, the nurse of Inhapy's niece Queen Ahmose-Nefertari. Her skin was still present, and no evidence of salt was found. The body was sprinkled with aromatic powdered wood and wrapped in resin soaked linen.[7] | |

| Ahmose-Sitamun | Sitamun | Unknown | 18th | Female | Unknown | N/A | Ahmose-Sitamun was found entombed in DB320. At some point she was moved to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo where she remains to this day. |

| Ahmose-Sitkamose | Sitkamose | Unknown | 17th/18th | Female | 1881 | Sitkamose's mummy was discovered in 1881 in the Deir el-Bahari cache. Her mummy was unwraped by Gaston Maspero on June 19, 1886 where it was found to be damaged by tomb robbers. Sitkamose was about thirty years old when she died, Grafton Eliot Smith described her as a strong-built, almost masculine woman.[8] | |

| Ahmose-Tumerisy | N/A | Unknown | 17th | Female | Unknown | N/A | Ahmose-Tumerisy was an ancient Egyptian princess of the late 17th Dynasty. Since her titles were "King's Daughter" and "King's Sister", it is likely that she was a daughter of pharaoh Seqenenre Tao and a sister of pharaoh Ahmose I. Her name is known from her coffin, which is now in the Hermitage Museum. Her mummy was found in the pit MMA 1019 in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna.[9] |

| Amenemhat | Son of Thutmose IV | Unknown | 18th | Male | Unknown | N/A | Amenemhat was a prince of the eighteenth dynasty of Egypt; the son of Pharaoh Thutmose IV.[10] He is depicted in the Theban tomb TT64, which is the tomb of the royal tutors Heqareshu and his son Heqaerneheh.[11] He died young and was buried in his father's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, KV43, together with his father and a sister called Tentamun.[12] His canopic jars and possible mummy were found there.[13] |

| Amenemope | Usermaatre Amenemope | 992 or 984 BC | 21st | Male | 1946 | N/A | While the tomb was discovered in 1940, his mummy was not found until the end of World War II. The mummy was found with various jewelry and two funerary masks which are now all displayed at the Cairo Museum. |

| Amenemopet | N/A | Unknown | 18th | Female | 1857 | N/A | The mummy of Amenemopet was buried in the Sheikh Abd el-Qurna cache where it was discovered in 1857. |

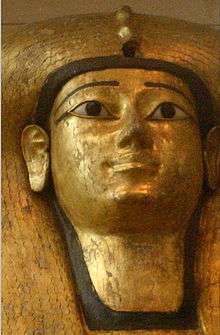

| Amenhotep I | Amenophis I | 1506 or 1504 BC | 18th | Male | Unknown | His mummy was moved sometime in the 20th or 21st Dynasty for safety, probably more than once. The mummy of Amenhotep I features an exquisite face mask which has caused his body not to be unwrapped by modern Egyptologists. | |

| Amenhotep II | Amenophis II | 1401 or 1397 BC | 18th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Amenhotep III | Amāna-Ḥātpa | 1353 or 1351 BC | 18th | Male | 1898 |  |

[14] |

| Ashayet | Ashait | Unknown | 11th | Female | Unknown | N/A | |

| Djedkare Isesi | Tancheres | Unknown | 5th | Male | 1940s | N/A | |

| Duathathor-Henuttawy | Henuttawy | Unknown | 20th | Female | Unknown | ||

| Hatshepsut | Hatchepsut | 1458 BC | 18th | Female | 1903 | N/A | |

| Henhenet | N/A | Unknown | 11th | Female | Unknown | N/A | |

| Henuttawy C | Henettawy | Unknown | 21st | Female | 1923-1924 | N/A | |

| Hornakht | Harnakht | Unknown | 22nd | Male | 1942 |  |

|

| Kamose | N/A | 1550 BC | 17th | Male | 1857 | N/A | In 1857, the mummy of Kamose was discovered seemingly deliberately hidden in a pile of debris. Egyptologists Auguste Mariette, and Heinrich Brugsch noted that the mummy was in very poor shape. |

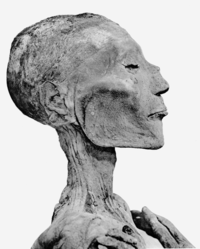

| Merneptah | Merenptah | 1203 BC | 19th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Mutnedjmet | Various | 1319 or 1332 BC | 18th | Female | Unknown | N/A | |

| Nauny | Nany | Unknown | 21st | Female | Unknown | N/A | |

| Nebetia | N/A | Unknown | 18th | Female | 1857 | N/A | |

| Neferefre | Raneferef | Unknown | 5th | Male | Unknown | N/A | |

| Nesitanebetashru | N/A | Unknown | 21st | Female | Unknown | ||

| Pentawer | Pentaweret | 1155 BC | 20th | Male | Unknown | ||

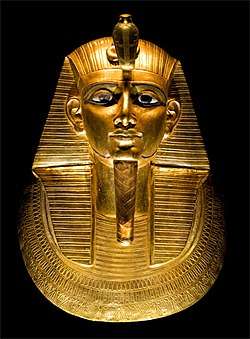

| Psusennes I | Pasibkhanu | 1001 BC | 21st | Male | 1940 |  |

|

| Ramesses I | Ramses | 1290 BC | 19th | Male | 1817 |  |

[15][16] |

| Ramesses II | Ramesses the Great | 1213 BC | 19th | Male | 1881 |  |

|

| Ramesses III | Usimare Ramesses III | 1155 BC | 20th | Male | 1886 |  |

|

| Ramesses IV | Heqamaatre Ramesses IV | 1149 BC | 20th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Ramesses V | Usermaatre Sekheperenre Ramesses V | 1145 BC | 20th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Ramesses VI | Ramesses VI Nebmaatre-Meryamun | 1137 BC | 20th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Ramesses IX | Amon-her-khepshef Khaemwaset | 1111 BC | 20th | Male | 1881 | N/A | |

| Ranefer | Ranofer | Unknown | 4th | Male | Unknown | N/A | |

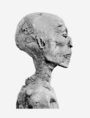

| Seqenenre Tao | • Seqenera Djehuty-aa, • Sekenenra Taa |

Unknown | 17th | Male | 1881 | ||

| Sesheshet | Sesh | Unknown | 6th | Female | 2009 | N/A | |

| Seti I | Sethos I | 1279 BC | 19th | Male | 1881 | .jpg) |

[17][18] |

| Seti II | Sethos II | 1193 BC | 19th | Male | 1908 |  |

|

| Siptah | Merenptah Siptah | 1191 BC | 19th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Sitdjehuti | Satdjehuti | Unknown | 17th | Female | 1820 | N/A | |

| Thutmose II | Various | 1479 BC | 18th | Male | 1881 |  |

[19][20] |

| Thutmose III | Various | 1425 BC | 18th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Thutmose IV | Menkheperure | 1391 or 1388 BC | 18th | Male | 1898 |  |

|

| Tiaa (princess) | N/A | Unknown | 18th | Female | 1857 | N/A | |

| Tiye | The Older Lady | 1338 BC | 18th | Female | 1898 |  |

Tiye was found to be extensively damaged by past tomb robbers. |

| Tutankhamun | King Tut | 1323 BC | 18th | Male | 1922 |  |

Main article: Tutankhamun's mummy |

| Tjuyu | • Thuya, • Thuyu |

1375 BC | 18th | Female | 1905 | N/A | |

| Webensenu | N/A | Unknown | 18th | Male | 1898 |  |

Webensenu was an ancient Egyptian prince of the 18th dynasty. He was a son of Pharaoh Amenhotep II.[21] He is mentioned, along with his brother Nedjem, on a statue of Minmose, overseer of the works in Karnak.[22] He died as a child and was buried in his father's tomb, KV35, where there were found his canopic jars and shabtis. His mummy is still there, and it indicates that he died around the age of ten.[23][24] |

Disputed

The following entries are previously identified mummies that are now in dispute. Over time through the advance in technology, new information comes to light that discredits old findings and beliefs. The mummies that have been lost or destroyed since initial discovery may never be properly identified.

| Assumed name(s) | Dynasty | Sex | Year discovered | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmose-Nefertari | 18th | Female | 1881 | Ahmose-Nefertari is assumed to have been retrieved from her tomb at the end of the New Kingdom and moved to the royal cache in DB320. Her presumed body, with no identification marks, was discovered in the 19th century and unwrapped in 1885 by Emile Brugsch but this identification has been challenged.[25] When the mummy was found it emitted such a bad odor that it was reburied on museum grounds in Cairo until the offensive smell abated. If this is Ahmose-Nefertari, then she was determined to have died in her 70s. The mummy's hair had been thinning and plaits of false hair had been woven in with its own to cover this up. The body also had been damaged in antiquity and was missing its right hand.[26] | |

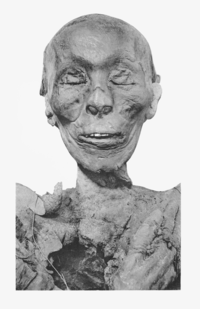

| Ahmose Sapair | 18th | Male | 1881 |  |

In 1881, a mummy of a 5- to 6-year-old boy was found in cache (DB320) and identified as Ahmose-Sipair. This was disputed as Prince Ahmose-Sipair is always portrayed as an adult on the coffin of the scribe and other antiquities, thus the child-mummy cannot be his.[27] |

| Akhenaten | 18th | Male | 1907 |  |

Uncertainty remains over the identity of this mummy as the young age at death is inconsistent with Akhenaten's reign. CT scans done in 2010 strongly suggest that the mummy may be Pharaoh Smenkhkare. |

| Ankhesenamun | 18th | Female | 1817 | N/A | Believed to be Ankhesenamun, as she is the mother of the two fetuses found in Tutankhamun's grave. Uncertainty remains if the mummy found in KV55 is accepted to be Akhenaten. She is also known as mummy KV21A from the tomb that she was discovered in. |

| Mayet | 11th | Female | 1921 | N/A | Mayet's position within the royal family of Mentuhotep II is disputed.[28] It is generally assumed that she was a daughter of the king as she was about five years old when she died. |

| • Nefertiti, • Nebetah, or • Beketaten |

18th | Female | 1898 |  |

• Main article: The Younger Lady Two main DNA tests have been done on this mummy which have resulted in three different possible identities. Early speculation was that the mummy belonged to Queen Nefertiti, and while DNA testing was done it neither confirmed nor denied this as being factual. DNA testing published in 2010 revealed her to be a daughter of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his chief wife Tiye; and the mother of Tutankhamun.[29] This DNA report concluded that the mummy is likely Beketaten, or Nebetah, but again no conclusive answer was found. In any case the mummy was found to be extensively damaged by past tomb robbers which caused numerous holes. |

| Setnakhte | 20th | Male | 1898 | The alleged mummy of Setnakhte has never been identified with certainty, although the so–called "mummy in the boat" found in KV35 was sometimes identified with him, an attribution rejected by Aidan Dodson who rather believes the body belonged to a royal family member of Amenhotep II of the 18th Dynasty. In any case the mummy was destroyed by looters in 1901, thus preventing any analysis on it.[30] | |

| Tetisheri | 17th/18th | Female | 1881 |  |

No tomb has yet been conclusively identified with Queen Tetisheri, though a mummy that may be hers was included among other members of the royal family that were reburied in the Royal Cache. |

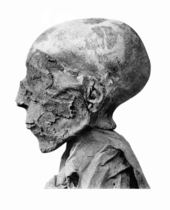

| Thutmose I | 18th | Male | 1881 |  |

Egyptologist Gaston Maspero thought this was the mummy of Thutmose I largely on the strength of familial resemblance to the mummies of Thutmose II and Thutmose III. In 2007 though, Dr. Zahi Hawass announced that the mummy is a thirty-year-old man who had died as a result of an arrow wound to the chest. Due to the young age of the mummy and the cause of death, it was determined that the mummy was probably not of Thutmose I.[31] |

See also

Notes

- Mummies have been found by archaeologists whom have determined their royal status, but have not been able to provide any conclusive name. These mummies are not listed here as not enough information is available on the subject.

References

- Shaw, Ian and Nicholson, Paul. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. p. 84. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1995. ISBN 0-8109-9096-2

- Ann Macy Roth, The Ahhotep Coffins, Gold of Praise: Studies of Ancient Egypt in honor of Edward F. Wente, 1999

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004) ISBN 0-500-05128-3, p. 128

- Demas, Martha, and Neville Agnew, eds. 2012. Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: Volume 1. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Conservation Institute. Getty Conservation Institute, link to article

- Smith, G Elliot. The Royal Mummies, pp. 15–17. Duckworth, 2000 (reprint).

- G.E. Smith, Catalogue General Antiquites Egyptiennes du Musee du Caire: The Royal Mummies, 1912, pp 6-8 and pl IV. Available via University of Chicago

- E.G. Smith, Catalogue General Antiquites Egyptiennes du Musee du Caire: The Royal Mummies, Cairo, 1912; retrieved from The University of Chicago Library

- Mummy of Ahmose-Sitkamose

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004) ISBN 0-500-05128-3, p. 128

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004) ISBN 0-500-05128-3, p.137

- Dodson & Hilton, p.134

- Dodson & Hilton, p.135

- Dodson & Hilton, p.137

- Beckerath, Jürgen von, Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz, (1997) p.190

- Jürgen von Beckerath, Chronologie des Äegyptischen Pharaonischen (Mainz: Phillip von Zabern, 1997), p.190

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge.

- Michael Rice (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge.

- J. von Beckerath (1997). Chronologie des Äegyptischen Pharaonischen (in German). Phillip von Zabern. p. 190.

- Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.204. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- Shaw, Ian; and Nicholson, Paul. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. p. 289. The British Museum Press, 1995

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004) ISBN 0-500-05128-3, p.141

- Wolfgang Helck: Urkunden der 18. Dynastie, Heft 18, Berlin 1956, pp. 1447

- Dodson & Hilton, pp.135,141

- Betsy Bryan: The 18th Dynasty before the Amarna Period, in Ian Shaw (editor): The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford, New York 2000, ISBN 978-0192804587, p. 248

- Dylan (July 22, 2014). "The so-called Royal Cachette TT 320 was not the grave of Ahmose Nefertari!". www.dylanb.me.uk. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- "XVIII'th Dynasty Gallery I". The Theban Royal Mummy Project. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Michael Rice: Who is who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London/New York 1999. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6, p. 117.

- Hawass, Zahi; Gad, Yehia Z.; Ismail, Somaia; Khairat, Rabab; Fathalla, Dina; Hasan, Naglaa; Ahmed, Amal; Elleithy, Hisham; Ball, Marcus; Gaballah, Fawzi; Wasef, Sally; Fateen, Mohamed; Amer, Hany; Gostner, Paul; Selim, Ashraf; Zink, Albert; Pusch, Carsten M. (February 2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 641. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. PMID 20159872. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Schneider, Thomas (2010). "Contributions to the Chronology of the New Kingdom and the Third Intermediate Period". Ägypten & Levante. 20., pp. 386–387

- Anderson, Lisa (14 July 2007). "Mummy awakens new era in Egypt". Chicago Tribune.