Ahmose-Nefertari

Ahmose-Nefertari of ancient Egypt was the first queen of the 18th Dynasty. She was a daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Ahhotep I, and royal sister and the great royal wife of Ahmose I. She was the mother of king Amenhotep I and may have served as his regent when he was young. Ahmose-Nefertari was deified after her death.

| Ahmose-Nefertari | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen consort of Egypt Great Royal Wife God's Wife of Amun Regent | |||||

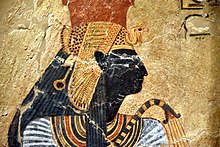

Ahmose Nefertari as depicted in tomb TT359 | |||||

| Spouse | Ahmose I | ||||

| Issue | Amenhotep I Ahmose-ankh Siamun Ramose ? Ahmose-Meritamun Mutnofret ? Ahmose-Sitamun | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | 18th Dynasty | ||||

| Father | Seqenenre Tao | ||||

| Mother | Ahhotep I | ||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||

| Ahmose-Nefertari in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ahmose Nefertari Jꜥḥ ms Nfr trj Born of Iah, the beautiful companion | ||||||||||||

Family

Ahmose-Nefertari was a daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Ahhotep I and the granddaughter of Senakhtenre and queen Tetisheri.[1] Ahmose-Nefertari was born in Thebes, likely during the reign of Senakhtenre Ahmose (not Tao—as this king's nomen has now been discovered to be 'Ahmose' like that of his grandson Ahmose I).[2][3] She grew up with quite a few brothers and sisters, including the princes Ahmose, Ahmose Sapair and Binpu, and the princesses Ahmose-Henutemipet, Ahmose-Tumerisy, Ahmose-Nebetta, Ahmose-Meritamon, as well as her half-sisters Ahmose-Henuttamehu, Ahmose and Ahmose-Sitkamose.[1]

Ahmose-Nefertari may have married Pharaoh Kamose but, if so, there is no record of such a marriage.[2] She did become the great royal wife of Ahmose I. With Ahmose she had at least three sons. She is depicted on a stela from Karnak with a son named Ahmose-ankh and a son named Siamun was reburied in the royal cache DB320. But it was her son Amenhotep I who would eventually succeed his father to the throne. She was the mother of queen Ahmose-Meritamun and Ahmose-Sitamun. She may also have been the mother of Mutnofret, the wife of Thutmose I. A prince named Ramose included among the Lords of the West and known from a statue now in Liverpool, may be another son of Ahmose-Nefertari.[1]

Life

Ahmose-Nefertari was born during the latter part of the 17th Dynasty, during the reign of her grandfather Senakhtenre Ahmose.[2] Her father Seqenenre Tao fought against the Hyksos and may have lost his life during a battle. He was succeeded by Kamose.[1] It is possible that Ahmose-Nefertari married Kamose, but no evidence exists of such a marriage.[2]

After the death of Kamose the throne went to Ahmose I. Pharaoh Ahmose was very young and queen-mother Ahhotep I served as regent during the early years of his reign. Ahhotep would have taken precedence at court over her daughter Ahmose-Nefertari, who was the great royal wife. Ahmose I became the first king of the 18th Dynasty, and a pharaoh ruling over a reunited country.[2]

Queen Ahmose-Nefertari held many titles, including those of hereditary princess (iryt-p`t), great of grace (wrt-im3t), great of praises (wrt-hzwt), king's mother (mwt-niswt), great king's wife (hmt-niswt-wrt), god's wife (hmt-ntr), united with the white crown (khnmt-nfr-hdjt), king's daughter (s3t-niswt), and king's sister (snt-niswt).[4] However, her preferred title was that of god's wife.[5] The queen was revered as "Goddess of Resurrection" and was arguably the most venerated women in Egyptian history.[6]

A donation stela from Karnak records how king Ahmose purchased the office of Second Prophet of Amun and endowed the position with land, goods and administrators. The endowment was given to Ahmose-Nefertari and her descendants, though she was the most prominent God's Wife of Amun. Separately the position of Divine adoratrix was also given to Ahmose-Nefertari.[7] Records from a later era indicate that in this position she would have been responsible for all temple properties, administration of estates, workshops, treasuries and all the associated administration staff.[8]

Amenhotep I came to power while he was still young. As his mother, Ahmose-Nefertari may have served as regent for him until he reached maturity.[7][9] Because of her position as regent for her son, some speculate that she started the Valley of the Kings.[10]

Ahmose-Nefertari is shown to be alive during the early years of the reign of Thutmose I. She is depicted in Nubia next to the Viceroy of Kush Ahmose called Turo in the company of the newly crowned king and Queen Ahmose. A vase fragment found in KV20 was inscribed with the double cartouche of king Tuthmose I and Ahmose-Nefertari and the epithet indicates the queen was alive. A large statue of queen Ahmose-Nefertari from Karnak may be one of the last statues created in her honor before she died.[11]

Death and burial

Ahmose-Nefertari likely died in approximately the fifth or sixth year of Thutmose I. Her death is recorded on the stela of a wab-priest called Nefer. The text mentions that “the divine consort Ahmose-Nefertari, justified with the great god lord of the West, flew to heaven". Helck proposed that the annual cult holiday (II Shemu 14) dedicated to Ahmose-Nefertari at Deir el-Medina may have commemorated the day of her death. The father of Nefer, who was likely none other that the overseer of the royal works Ineni, oversaw her burial.[11]

She was likely buried in Dra Abu el-Naga, and had a mortuary temple there. Her mummy is assumed to have been retrieved from her tomb at the end of the New Kingdom and moved to the royal cache in DB320. Her presumed body, with no identification marks, was discovered in the 19th century and unwrapped in 1885 by Emile Brugsch but this identification has been challenged.[12] The mummy emitted such a bad odor that Brugsch had it reburied on museum grounds in Cairo until the offensive smell abated. Ahmose-Nefertari died in her 70s. Her hair had been thinning and plaits of false hair had been woven in with her own to cover this up. Her body had been damaged in antiquity and was missing her right hand.[7]

Deification and iconography

In the Theban region – and especially in the village of Deir el-Medina – she is mentioned or depicted in at least 50 private tombs and even a greater amount of objects which are datable from the reign of Thutmose III to the end of the 20th Dynasty.[9][13]:201–2 When Amenhotep died he became the center of a village funerary cult, worshiped as "Amenhotep of the Town". When the Queen died she also was deified and became "Mistress of the Sky" and "Lady of the West".[7][14]

In most depictions of Ahmose-Nefertari, she is pictured with black skin,[15] while in some instances her skin is blue.[16] In 1939 Flinders Petrie suggested that Ahmose-Nefertari might have been of Nubian descent, but he also acknowledged the possibility of the skin color being purely symbolic.[17] In 1961 Alan Gardiner, in describing the walls of tombs in the Der el-Medina area, noted in passing that Ahmose-Nefertari was "well represented" in these tomb illustrations, and that her countenance was sometimes black and sometimes blue. He did not offer any explanation for these colors, but noted that her probable ancestry ruled out that she might have had black blood.[16] In 1974, Diop described her as "typically negroid."[18]:17 In the controversial book Black Athena, Martin Bernal regarded her skin color in paintings as a clear sign of Nubian ancestry.[19] In more recent times, scholars such as Joyce Tyldesley, Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes, and Graciela Gestoso Singer, argued that her skin color is indicative of her role as a goddess of resurrection, since black is both the color of the fertile land of Egypt and that of the underworld.[7]:90[20][6] In a wooden votive statue of Ahmose-Nefertari, currently in the Louvre museum, her skin was painted red.[21]

References

- Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- Forbes, Dennis C. Imperial Lives: Illustrated Biographies of Significant New Kingdom Egyptians. KMT Communications, Inc. 1998. ISBN 1-879388-08-1

- Sébastien Biston-Moulin, "Le roi Sénakht-en-Rê Ahmès de la XVIIe dynastie", ENIM 5, pp. 61–71, 22 mars/march 2012 [online:

- Grajetzki, Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Golden House Publications, London, 2005, ISBN 978-0-9547218-9-3

- Alameen-Shavers, Antwanisha (2018-05-20). "Not a Trophy Wife: (Re)Interpreting the Position Held by Queens of Kemet During the New Kingdom as a Political Seat". Journal of Black Studies. 49 (7): 647–671. doi:10.1177/0021934718773739. ISSN 0021-9347.

- Graciela Gestoso Singer, "Ahmose-Nefertari, The Woman in Black". Terrae Antiqvae, January 17, 2011

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- "The Great Goddesses of Egypt", Barbara S. Lesko, p. 246, University of Oklahoma Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8061-3202-7

- Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000. ISBN 0-19-280458-8

- Fletcher, Joann (2014). The search for nefertiti : the true story of an amazing discovery. Morrow. ISBN 9780062106360. OCLC 877888764.

- Louise Bradbury, Nefer's Inscription: On the Death Date of Queen Ahmose-Nefertary and the Deed Found Pleasing to the King, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 22 (1985), pp. 73-95

- The so-called Royal Cachette TT 320 was not the grave of Ahmose Nefertari

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell Books. ISBN 9780631174721.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (1996). "Hatchespsut: The Female Pharaoh", p.62, Viking, ISBN 0-670-85976-1.

- Gitton, Michel (1973). "Ahmose Nefertari, sa vie et son culte posthume". École Pratique des Hautes études, 5e Section, Sciences Religieuses. 85 (82): 84. doi:10.3406/ephe.1973.20828. ISSN 0183-7451.

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1961). Egypt of the Pharaohs: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University press., p.175

- Petrie, Flinders (1939). The making of Egypt. London. p.155

- Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 1-118. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- Martin Bernal (1987), Black Athena: Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. The Fabrication of Ancient Greece, 1785-1985, vol. I. New Jersey, Rutgers University Press

- Hodel-Hoenes, S & Warburton, D (trans), Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes, Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 268.

- https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/former-queen-ahmose-nefertari-protectress-royal-tomb-workers-deified

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ahmose-Nefertari. |

- Ahmose Nefertari Image of her coffin and short bio.

- Mummy of Ahmose-Nefertari by Max Miller.

- "Women in ancient Egypt"

- "Women in Power BCE 4500-1000"

- "Royal Women"

- Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Ahmose-Nefertari (see index)