Limnarchia

Limnarchia is a clade of temnospondyls. It includes the mostly Carboniferous-Permian age Dvinosauria and the mostly Permian-Triassic age Stereospondylomorpha. The clade was named in a 2000 phylogenetic analysis of stereospondyls and their relatives. Limnarchia means "lake rulers" in Greek, in reference to their aquatic lifestyles and long existence over a span of approximately 200 million years from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Cretaceous. In phylogenetic terms, Limnarchia is a stem-based taxon including all temnospondyls more closely related to Parotosuchus than to Eryops. It is the sister group of the clade Euskelia, which is all temnospondyls more closely related to Eryops than to Parotosuchus. Limnarchians represent an evolutionary radiation of temnospondyls into aquatic environments, while euskelians represent a radiation into terrestrial environments. While many euskelians were adapted to life on land with strong limbs and bony scutes, most limnarchians were better adapted for the water with poorly developed limbs and lateral line sensory systems in their skulls.[1]

| Limnarchia | |

|---|---|

| |

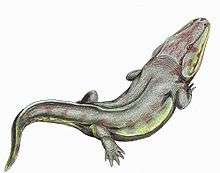

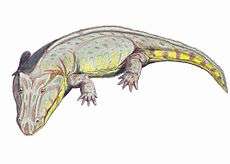

| Life restoration of Parotosuchus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Clade: | †Limnarchia Yates and Warren, 2000 |

| Subgroups | |

Chinlestegophis, a putative Triassic stereospondyl considered to be related to metoposauroids such as Rileymillerus, has been noted to share many features with caecilians, a living group of legless burrowing amphibians. If Chinlestegophis is indeed both an advanced stereospondyl and a relative of caecilians, this means that limnarchians (in the form of caecilians) survived to the present day.[2]

Description

Several characteristics unique to Limnarchia were identified when the clade was named in 2000. Most of these characteristics, called synapomorphies, relate to the shapes of bones on the underside and back of the skull. Limnarchian synapomorphies include the presence of a row of teeth stemming from the ectopterygoid bone on the palate, the maxilla bone touching the vomer near the edge of the palate (these bones are separated by an opening in euskelian skulls), and the lack of bony projections called denticles on the vomer. Other characteristic features of limnarchians include the extension of the lower jaw behind the jaw joint, and a small hole called the paraquadrate foramen at the back of the skull. The only limnarchian synapomorphy not found in the skull is the elongated shape of the interclavicle bone in the pectoral girdle.[1]

Phylogeny

Yates and Warren (2000) erected Limnarchia in their phylogenetic study of stereospondyls and their relatives. They found support for two major divisions of temnospondyls, which they named Euskelia and Limnarchia. Limnarchia included a group of small-bodied aquatic temnospondyls called Dvinosauria as the most basal members of the clade, followed by the large-bodied Archegosauroidea and the diverse Stereospondyli, which together formed the clade Stereospondylomorpha. Below is a cladogram from Yates and Warren (2000) showing this phylogeny:[1][3]

| Temnospondyli |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Some more recent phylogenetic analyses such as Ruta et al. (2007) place Dvinosauria outside the Euskelia-Limnarchia split as much more basal temnospondyls.[4] If this is the case, Limnarchia would include the same taxa as Stereospondylomorpha.

References

- Yates, A. M.; Warren, A. A. (2000). "The phylogeny of the 'higher' temnospondyls (Vertebrata: Choanata) and its implications for the monophyly and origins of the Stereospondyli". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 128: 77–121. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00650.x.

- Pardo, Jason D.; Small, Bryan J.; Huttenlocker, Adam K. (2017-07-03). "Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light on the origins of Lissamphibia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (27): E5389–E5395. doi:10.1073/pnas.1706752114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5502650. PMID 28630337.

- Sigurdsen, T.; Bolt, J.R. (2010). "The Lower Permian amphibamid Doleserpeton (Temnospondyli: Dissorophoidea), the interrelationships of amphibamids, and the origin of modern amphibians". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1360–1377. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501445.

- Ruta, M.; Pisani, D.; Lloyd, G. T.; Benton, M. J. (2007). "A supertree of Temnospondyli: cladogenetic patterns in the most species-rich group of early tetrapods". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1629): 3087–3095. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1250. PMC 2293949. PMID 17925278.