Liberalism in Turkey

This article gives an overview of liberalism in Turkey. Liberalism was introduced in the Ottoman Empire during the Tanzimat period of reformation.

History

On 30 May 1876, Murad V became the Sultan when his uncle Abdülaziz was deposed. He was highly influenced by French culture and was a liberal.[1][2][3][4] He reigned for 93 days before being deposed on the grounds that he was supposedly mentally ill in 31 August 1876; however his opponents may simply have used those grounds to stop his implementation of democratic reforms. As a result, he was unable to deliver the Constitution that his supporters had sought.[4][2]

Constitutional era

Constitutionalism was introduced in the Ottoman Empire by liberal intellectuals who tried to modernize their society by promoting development, progress, and liberal values.[5]

Tanzimât

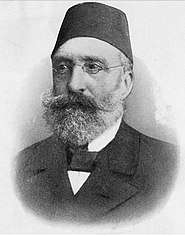

The Tanzimât, literally meaning reorganization of the Ottoman Empire (see Nizam), was a period of reformation that began in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876.[6] Although the motives for the implementation of Tanzimât were burocratic, it was impulsed by liberal ministers and intellectuals like Dimitrios Zambakos Pasha, Kabuli Mehmed Pasha, the secret society Young Ottomans,[7][8] and Midhat Pasha, who is also often considered as one of the founders of the Ottoman Parliament.[9][10][11][12] Many changes were made to improve civil liberties, but many Muslims saw them as foreign influence on the world of Islam. That perception complicated reformist efforts made by the state.[13] A policy called Ottomanism was meant to unite all the different peoples living in Ottoman territories, "Muslim and non-Muslim, Turkish and Greek, Armenian and Jewish, Kurd and Arab". The policy officially began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839, declaring equality before the law for both Muslim and non-Muslim Ottomans.[14]

The Tanzimât reforms began under Sultan Mahmud II. On November 3, 1839, Sultan Abdulmejid I issued a hatt-i sharif or imperial edict called the Edict of Gülhane or Tanzimât Fermânı. This was followed by several statutes enacting its policies. In the edict the Sultan stated that he wished "to bring the benefits of a good administration to the provinces of the Ottoman Empire through new institutions." Among the reforms were the abolition of slavery and slave trade;[15] the decriminalization of homosexuality; the establishment of the Civil Service School, an institution of higher learning for civilians[16] the Press and Journalism Regulation Code;[15][16] and the Nationality Law of 1869 creating a common Ottoman citizenship irrespective of religious or ethnic divisions; among others. Western educated economists like Ahmet Reşat Pasha advocated for economic liberalism.[17]

Young Ottomans

The Young Ottomans were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman Turkish intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the Tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough, and wanted to end the autocracy in the empire.[18][19] Young Ottomans sought to transform Ottoman society by preserving the empire and modernizing along the European tradition of adopting a constitutional government.[20] Though the Young Ottomans were frequently in disagreement ideologically, they all agreed that the new constitutional government should continue to be somewhat rooted in Islam to emphasize "the continuing and essential validity of Islam as the basis of Ottoman political culture."[21] However, they sincreticize Islamic idealism with modern liberalism and parliamentary democracy, to them the European parliamentary liberalism was a model to follow, in accordance with the tenets of Islam and "attempted to reconcile Islamic concepts of government with the ideas of Montesquieu, Danton, Rousseau, and contemporary European Scholars and statesmen."[22][23][24] Namık Kemal, who was influential in the formation of the society, admired the constitution of the French Third Republic, he summed up the Young Ottomans' political ideals as "the sovereignty of the nation, the separation of powers, the responsibility of officials, personal freedom, equality, freedom of thought, freedom of press, freedom of association, enjoyment of property, sanctity of the home".[22][23][24] The Young Ottomans believed that one of the principal reasons for the decline of the empire was abandoning Islamic principles in favor of imitating European modernity with unadvised compromises to both and they sought to unite the two in a way that they believed would best serve the interests of the state and its people.[25] They sought to revitalize the empire by incorporating certain Europeans models of government, while still retaining the Islamic foundations the empire was founded on.[26] Among the prominent members of this society were writers and publicists such as İbrahim Şinasi, Namık Kemal, Ali Suavi, Ziya Pasha, and Agah Efendi.

In 1876, the Young Ottomans had their defining moment when Sultan Abdülhamid II reluctantly promulgated the Ottoman constitution of 1876 (Turkish: Kanûn-u Esâsî), the first attempt at a constitution in the Ottoman Empire, ushering in the First Constitutional Era. Although this period was short lived, with Abdülhamid ultimately suspending the constitution and parliament in 1878 in favor of a return to absolute monarchy with himself in power,[27] the legacy and influence of the Young Ottomans continued to endure until the collapse of the empire. Several decades later, another group of reform-minded Ottomans, namely the Young Turks, repeated the Young Ottomans' efforts, leading to the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era.

Freedom and Accord Party

- 1911: As a reaction to dictatorial tendencies, the liberal Freedom and Accord Party (Hürriyet ve İtilaf Fırkası) is founded.

- 1913: The party is banned.

Ottoman Liberal People's Party / Freedom Party

- 1918: Fethi Okyar founded in 1918 the Ottoman Liberal People's Party (Osmanlı Hürriyetperver Avam Fırkası).

- 1920: The party disappeared.

- 1930: In an attempt to allow a legal opposition party, Atatürk encouraged Okyar to found the Freedom Party (Hürriyet Fırkası), also rendered as Liberal Republican Party (Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırkası).

- 1930: The party attracted huge number of dissident people of the Kemalist bureaucracy's harsh policies. The founder of the party, Okyar, dissolved his own party, fearing that it was becoming a rallying ground for counter-reformists against the secular republic.

Freedom Party

- 1956: A liberal faction of the Democratic Party founded the Freedom Party (Hürriyet Partisi).

- 1958: The party merged into the Republican People's Party.

New Turkey Party

- 1961: A moderate faction of the former Democratic Party established after the ban of the latter party the New Turkey Party (Yeni Türkiye Partisi).

- 1973: After initial success the party became unsuccessful and is dissolved.

Liberal Democratic Party

- 1994: Founded on July 26 as Liberal Party by former (Demokrat Parti) members and Besim Tibuk, first president

- 1996: The Liberal Party changed its name to Liberal Democratic Party

- 2002: Besim Tibuk resigns as president on November 25.

- 2005: Cem Toker gets elected as president on July 20.

Peoples' Democratic Party

Founded in 15 October 2012, the Peoples' Democratic Party is a liberal pro-minority political party.[28][29][30] Generally left-wing, the party places a strong emphasis on democracy,[31] feminism,[32] minority rights.[30][33][34][35] It is an associate member of the Party of European Socialists (PES), consultative member of the Socialist International and member of Progressive Alliance.[36][37][38]

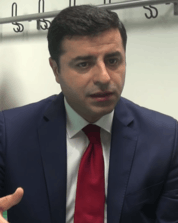

For the June 2015 general election, the HDP took the decision to field candidates as a party despite the danger of potentially falling below the 10% threshold. Even though most of the politicians from HDP are secular left-wing Kurds, the candidate list included devout Muslims, socialists, Alevis, Armenians, Syriac Christians, Azerbaijanis, Circassians, Lazi, Romanis and LGBT activists. Of the 550 candidates, 268 were women.[39][40][41] In 2015, Barış Sulu was the first openly gay parliamentary candidate in Turkey as a candidate of the HDP.[42] Other notable members are former chairwoman Figen Yüksekdağ,[43] former chairman Selahattin Demirtaş[44] and spokesperson Osman Baydemir.[45]

Figen Yüksekdağ (born 1971) was a former co-leader of the left-wing Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) of Turkey from 2014 to 2017,[46][47] serving alongside Selahattin Demirtaş. She was a Member of Parliament for Van since the June 2015 general election until her parliamentary membership was revoked by the courts on 21 February 2017 during the 2016–17 Turkish purges.[48] Selahattin Demirtaş and her party membership and therefore they co-leadership positions were revoked by the courts on 9 March 2017 following a six-year prison sentence for distributing terrorist propaganda.[49] Born from Turkish Sunni farming family,[50][51] she was an independent parliamentary candidate for the Adana electoral district in the 2002 general election. She was involved in women's rights movements for several years before becoming the editor of the Socialist Woman magazine. While serving on the board of the Atılım newspaper, she was taken into custody in 2009 due to her political activity. She cofounded the Socialist Party of the Oppressed (ESP)[52] shortly after in 2010 and resigned as leader in 2014 to join the HDP, with which the ESP merged later the same year. During the second ordinary congress of the HDP, she was elected the co-leader of the HDP.[43]

References

- Howard, Douglas Arthur (2001). The History of Turkey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 66. ISBN 0313307083. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Smith, Jean Reeder; Smith, Lacey Baldwin (1980). Essentials of World History. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0812006372. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Yapp, Malcolm (9 January 2014). The Making of the Modern Near East 1792-1923. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 1317871073. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Palmer, Alan. The Decline and Fall of the Ottoman Empire, 1992. Page 141–143.

- Lindgren, Allana; Ross, Stephen (2015). The Modernist World. Routledge. p. 440. ISBN 1317696166. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Cleveland, William L & Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East: 4th Edition, Westview Press: 2009, p. 82.

- Lindgren, Allana; Ross, Stephen (2015). The Modernist World. Routledge. ISBN 1317696166. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Yapp, Malcolm (9 January 2014). The Making of the Modern Near East 1792-1923. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 1317871073. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Hanioglu, M. Sukru (1995). The Young Turks in Opposition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195358023. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- The Syrian Land: Processes of Integration and Fragmentation : Bilād Al-Shām from the 18th to the 20th Century. Franz Steiner Verlag. 1998. p. 260. ISBN 3515073094. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Zvi Yehuda Hershlag (1980). Introduction to the Modern Economic History of the Middle East. Brill Archive. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-90-04-06061-6. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- Caroline Finkel (19 July 2012). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923. John Murray. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-84854-785-8. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Roderic. H. Davison, Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774-1923 – The Impact of West, Texas 1990, pp. 115-116.

- The Invention of Tradition as Public Image in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1808 to 1908, Selim Deringil, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Jan. 1993), pp. 3-29

- NTV Tarih Archived 2013-02-12 at the Wayback Machine history magazine, issue of July 2011. "Sultan Abdülmecid: İlklerin Padişahı", pages 46-50. (Turkish)

- Cleveland & Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, Chapter 5 pg.84 of 4th edition

- https://www.biyografya.com/biyografi/14145

- Akgunduz, Ahmet; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History: Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. p. 318. ISBN 9090261087.

- Ahmad, Feroz (2014). Turkey: The Quest for Identity. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1780743025. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 496. ISBN 0521779332.

- Finkel 2006, p. 475.

- Berger, Stefan; Miller, Alexei (2015). Nationalizing Empires. Central European University Press. p. 447. ISBN 9633860164. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Black, Antony (2011). The History of Islamic Political Thought: From the Prophet to the Present. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748688781. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü (2008). A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-14617-9. p. 104.

- Zürcher 2004, p. 78.

- A History of the Modern Middle East. Cleveland and Buntin p.78

- Finkel 2006, p. 489-490.

- "HDK partileşti HDP oldu". 18 October 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Yavuz Önen biyografisi burada ünlülerin biyografileri burada". biyografi.net. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- "Parti programı" (in Turkish). HDP.org.tr. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "Turkey's Pro-Kurdish HDP Bets on New Voters to Exceed Threshold in June Polls". New York Times. 13 April 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "The Man Who Defied Erdoğan".

- "Court orders ban on HDP election brochures for promoting 'self-governance'". 19 October 2015. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Turkey arrests pro-Kurdish MPs from only party with pro-LGBT policies". PinkNews. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Editor, Nick Robins-Early Associate World; Post, The Huffington (8 June 2015). "Meet The Pro-Gay, Pro-Women Party Shaking Up Turkish Politics". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 December 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "PES congratulates associate parties HDP and CHP with historic election result". Party of European Socialists. 8 June 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- "Consultative parties". Socialist International. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- http://progressive-alliance.info/network/parties-and-organisations/

- "Inclusive HDP candidate list aspires to pass 10 pct election threshold". Hurriyet Daily News. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "HDP'den MHP'nin Doğu'daki Kalesine Azeri Kadın Aday". Haberler. 8 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "HDP'den Laz Aday Adayı". Bizim Kocaeli. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- First-ever openly gay parliamentary candidate stands for election in Turkey The Independent, 25 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "ESP'nin Genel Başkanı Bir Kadın: Figen Yüksekdağ - kadın-lgbti". Bianet - Bagimsiz Iletisim Agi.

- "Kurdish problem-focused HDP announces co-chair Demirtaş as presidential candidate". 30 June 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "HDP Merkez Yürütme Kurulu Olağanüstü Toplantısı Sonuçları" (in Turkish). HDP.org.tr. 24 February 2017.

- "ESP Genel Başkanı; Figen Yüksekdağ". Archived from the original on 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- EZİLENLERİN SOSYALİST PARTİSİ (ESP) Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.milliyet.com.tr/figen-yuksekdag-in-milletvekilligi-siyaset-2400426/

- http://www.dw.com/tr/figen-yüksekdağın-hdp-üyeliği-düşürüldü/a-37874506

- Laura Secorun Palet (6 April 2015). "Meet Figen Yüksekdağ, Turkey's Political Firestarter". Huffigton Post. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- Pinar Tremblay (11 February 2015). "Kurdish women's movement reshapes Turkish politics". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- Yvo Fitzherbert (21 July 2015). "Suruç massacre: today we mourn, tomorrow we rebuild". Roar Magazine. Retrieved 23 July 2015.