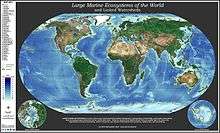

Large marine ecosystem

Large marine ecosystems (LMEs) are regions of the world's oceans, encompassing coastal areas from river basins and estuaries to the seaward boundaries of continental shelves and the outer margins of the major ocean current systems. They are relatively large regions on the order of 200,000 km² or greater, characterized by distinct bathymetry, hydrography, productivity, and trophically dependent populations. Productivity in LME protected areas is generally higher than in the open ocean.

The system of LMEs has been developed by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to identify areas of the oceans for conservation purposes. The objective is to use the LME concept as a tool for enabling ecosystem-based management to provide a collaborative approach to management of resources within ecologically-bounded transnational areas. This will be done in an international context and consistent with customary international law as reflected in 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.[1]

Although the LMEs cover mostly the continental margins and not the deep oceans and oceanic islands, the 66 LMEs produce about 80% of global annual marine fishery biomass.[2] In addition, LMEs contribute $12.6 trillion[3] in goods and services each year to the global economy. Due to their close proximity to developed coastlines, LMEs are in danger of ocean pollution, overexploitation, and coastal habitat alteration. NOAA has conducted studies of principal driving forces affecting changes in biomass yields for 33 of the 66 LMEs, which have been peer-reviewed and published in ten volumes.[4]

LME-based conservation is based on recognition that the world's coastal ocean waters are degraded by unsustainable fishing practices, habitat degradation, eutrophication, toxic pollution, aerosol contamination, and emerging diseases, and that positive actions to mitigate these threats require coordinated actions by governments and civil society to recover depleted fish populations, restore degraded habitats and reduce coastal pollution. Five modules are considered when assessing LMEs: productivity, fish and fisheries, pollution and ecosystem health, socioeconomics, and governance.[5] Periodically assessing the state of each module within a marine LME is encouraged to ensure maintained health of the ecosystem and future benefit to managing governments.[6]

Modules of Ecosystem Condition

Productivity

The productivity of a marine ecosystem can be measured in several ways. Measurements pertaining to zooplankton biodiversity and species composition, zooplankton biomass, water-column structure, photosynthetically active radiation, transparency, chlorophyll-a, nitrate, and primary production are used to assess changes in LME productivity and potential fisheries yield.[7] Sensors attached to the bottom of ships or deployed on floats can measure these metrics and be used to quantitatively describe changes in productivity alongside physical changes in the water column such as temperature and salinity.[8][9][10] This data can be used in conjunction with satellite measurements of chlorophyll and sea surface temperatures to validate measurements and observe trends on greater spatial and temporal scales.

Fish and Fisheries

Bottom-trawl surveys and pelagic-species acoustic surveys are used to assess changes in fish biodiversity and abundance in LMEs. Fish populations can be surveyed for stock identification, length, stomach content, age-growth relationships, fecundity, coastal pollution and associated pathological conditions, as well as multispecies trophic relationships.[11] Fish trawls can also collect sediment and inform us about ocean-bottom conditions such as anoxia.

Pollution and Ecosystem Health

Pollution and eutrophication can have significant impacts on ecosystem health and result in changing biomass yields. LMEs are emplaced in an effort to maintain healthy and sustainable conditions in spite of environmental change and global warming. A health ecosystem should maintain a relatively constant metabolic activity level, internal structure and organization, making it resistant to change over time.[12] Health is assessed on both a population and species level. Observations are made pertaining to bioaccumulation of contaminants, frequency of harmful algal blooms and diseases, water column contents and water quality, reproductive capacity and more.[13][14] Eutrophication and nutrient overloading can be measured as a function of nitrogen and phosphate in a given location.[15]

Socioeconomic

By integrating socioeconomic metrics with ecosystem management solutions, scientific findings can be utilized to benefit both the environment and economy of local regions. Management efforts must be practical and cost-effective. The Department of Natural Resource Economics at the University of Rhode Island has created a method for measuring and understanding the human dimensions of LMEs and for taking into consideration both socioeconomic and environmental costs and benefits of managing Large Marine Ecosystems.[16][17][18] This is especially important in island nations and small states which depend heavily on fisheries production for income.

Governance

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) aids in managing LMEs off the coasts of Africa and Asia by creating resource management agreements between environmental, fisheries, energy and tourism ministers of bordering countries. This means participating countries share knowledge and resources pertaining to local LMEs to promote longevity and recovery of fisheries and other industries dependent upon LMEs.[19]

LMEs around the Globe

- East Bering Sea

- Gulf of Alaska

- California Current

- Gulf of California

- Gulf of Mexico

- Southeast U.S. Continental Shelf

- Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf

- Scotian Shelf

- Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf

- Insular Pacific-Hawaiian

- Pacific Central-American Coastal

- Caribbean Sea

- Humboldt Current

- Patagonian Shelf

- South Brazil Shelf

- East Brazil Shelf

- North Brazil Shelf

- West Greenland Shelf

- East Greenland Shelf

- Barents Sea

- Norwegian Shelf

- North Sea

- Baltic Sea

- Celtic-Biscay Shelf

- Iberian Coastal

- Mediterranean Sea

- Canary Current

- Guinea Current

- Benguela Current

- Agulhas Current

- Somali Coastal Current

- Arabian Sea

- Red Sea

- Bay of Bengal

- Gulf of Thailand

- South China Sea

- Sulu-Celebes Sea

- Indonesian Sea

- North Australian Shelf

- Northeast Australian Shelf/Great Barrier Reef

- East-Central Australian Shelf

- Southeast Australian Shelf

- Southwest Australian Shelf

- West-Central Australian Shelf

- Northwest Australian Shelf

- New Zealand Shelf

- East China Sea

- Yellow Sea

- Kuroshio Current

- Sea of Japan

- Oyashio Current

- Sea of Okhotsk

- West Bering Sea

- Chukchi Sea

- Beaufort Sea

- East Siberian Sea

- Laptev Sea

- Kara Sea

- Iceland Shelf

- Faroe Plateau

- Antarctica

- Black Sea

- Hudson Bay

- Arctic Ocean

References

- NOAA.gov

- "LME Introduction".

- Costanza R, d'Arge R, Groots Rd, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O'Neill RV, Paruelo J and others. 1997. The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387:253-260.

- NOAA.gov

- Olsen SB, Sutinen JG, Juda L, Hennessey TM, Grigalunas TA. 2006. A Handbook on Governance and Socioeconomics of Large Marine Ecosystems. Kingston, RI: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island. 94 p.

- Wang H. 2004. An evaluation of the modular approach to the assessment and management of large marine ecosystems. Ocean Development and International Law 35:267-286.

- Pauly D, Christensen V. 1995. Primary production required to sustain global fisheries. Nature 374:255-257.

- Aiken J, Pollard R, Williams R, Griffiths G, Bellan I. 1999. Measurements of the upper ocean structure using towed profiling systems. In: Sherman K, Tang Q, editors. Large marine ecosystems of the Pacific Rim: Assessment, sustainability, and management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science, Inc. p 346-362.

- Berman MS, Sherman K. 2001. A towed body sampler for monitoring marine ecosystems. Sea Technology 42(9):48-52.

- SAHFOS. 2008. Annual Report 2007. Plymouth, UK: The Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science.

- Sea Around Us Project at www.seaaroundus.org/

- Costanza R. 1992. Toward an operational definition of ecosystem health. In: Costanza R, Norton BG, Haskell BD, editors. Ecosystem health: New goals for environmental management. Washington, DC: Island Press. p 239-256.

- Sherman B. 2000. Marine ecosystem health as an expression of morbidity, mortality, and disease events. Marine Pollution Bulletin 41(1-6):232-54.

- Sherman BH. 2001. Assessment of multiple marine ecological disturbances: Applying the North American prototype to the Baltic Sea Ecosystem. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment 7(5):1519-1540.

- Seitzinger S, Sherman K, Lee R. 2008. Filling Gaps in LME Nitrogen Loadings Forecast for 64 LMEs, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Technical Series 79. Paris, France: UNESCO.

- Sutinen J, ed. 2000. A framework for monitoring and assessing socioeconomics and governance of large marine ecosystems. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-158:32p.

- Sutinen, J.G. , P. Clay, C.L. Dyer, S.F. Edwards, J. Gates, T. Grigalunas, T. Hennesey, L. Juda, A.W. Kitts, P. Thunberg, H.R. Upton, and J.B. Walden. 2005. A framework for monitoring and assessing socioeconomics and governance of large marine ecosystems. 27-81 In, Hennessey, T.M. and J.G. Sutinen (Editors), Sustaining Large Marine Ecosystems: The human dimension. Elsevier.368p.

- Duda, A.M.. 2005.Targeting development assistance to meet WSSD goals for large marine ecosystems and small island developing states. Ocean & Coastal Management 48:1014

- Juda L, Hennessey T. 2001. Governance profiles and the management of the uses of large marine ecosystems. Ocean Development and International Law 32:41-67.