Alpinia galanga

Alpinia galanga,[1] a plant in the ginger family, bears a rhizome used as an herb in Southeast Asian cookery. It is one of four plants known as "galangal", and is differentiated from the others with the common names lengkuas, greater galangal, and blue ginger.

| Alpinia galanga | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Zingiberales |

| Family: | Zingiberaceae |

| Genus: | Alpinia |

| Species: | A. galanga |

| Binomial name | |

| Alpinia galanga | |

Names

The name "galangal" is probably derived from Persian qulanjan or Arabic khalanjan, which in turn may be an adaptation of Chinese gao liang jiang. Its names in India is derived from the same root, including kulanja in Sanskrit, kulanjan in Hindi, and kholinjan in Urdu.[2]

The name "lengkuas", on the other hand, is derived from Malay lengkuas, which is derived from Proto-Western Malayo-Polynesian *laŋkuas, with cognates including Ilokano langkuás; Tagalog, Bikol, Kapampangan, Visayan, and Manobo langkáuas or langkáwas; Aklanon eangkawás; Kadazan Dusun hongkuas; Ida'an lengkuas; Ngaju Dayak langkuas; and Iban engkuas. Some of the names have become generalized and are also applied to other species of Alpinia as well as for Curcuma zedoaria.[3]

Alpinia galanga is also called laos Javanese and laja in Sundanese. Other names include romdeng (រំដេង) in Cambodia; pa de kaw (ပတဲကော) in Myanmar; kha in Thailand; nankyo in Japan; and hong dou kou in Mandarin Chinese.[4] In Tamil it is known as a "பேரரத்தை or பெரியரத்தை" ("Pae-reeya-ra-thai), widely used in Siddha Medicine and in culinaries.

History of domestication

Lengkuas is native to Southeast Asia. Its original center of cultivation during the spice trade was Java, and today it is still cultivated extensively in Island Southeast Asia, most notably in the Greater Sunda Islands and the Philippines. Its cultivation has also spread into Mainland Southeast Asia, most notably Thailand.[5][6] Lengkuas is also the source of the leaves used to make nanel among the Kavalan people of Taiwan, a rolled leaf instrument used as a traditional children's toy common among Austronesian cultures.[7]

Description

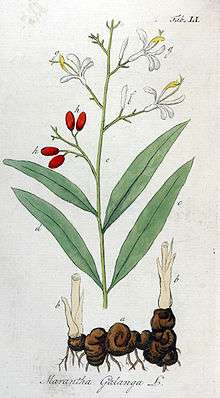

The plant grows from rhizomes in clumps of stiff stalks up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in height with abundant long leaves that bear red fruit. This plant's rhizome is the "galangal" used most often in cookery. It is valued for its use in food and traditional medicine, and is regarded as being superior to ginger. The rhizome has a pungent smell and strong taste reminiscent of black pepper and pine needles. Red and white cultivars are often used differently, with red cultivars being primarily medicinal, and white cultivars primarily as a spice.[5][6] The red fruit is used in traditional Chinese medicine and has a flavor similar to cardamom.

Culinary uses

The rhizome is a common ingredient in Thai curries and soups, where it is used fresh in chunks or cut into thin slices, mashed and mixed into curry paste. Indonesian rendang is usually spiced with galangal.

Traditional medicine

_Willd.jpg)

Under the names 'chewing John', 'little John to chew', and 'court case root', it is used in African American folk medicine and hoodoo folk magic. Ayurveda considers A. galanga (Sanskrit:-rasna) as a Vata Shamana drug. Known as பேரரத்தை (perarathai) in Tamil, this form of ginger is used with licorice root, called in Tamil athi-mathuram (Glycyrrhiza glabra) as folk medicine for colds and sore throats.

Potential pharmacology

The rhizome has been shown to have weak antimalarial activity in mice.[8]

Chemical constituents

Alpinia galanga rhizome contains the flavonol galangin.[9]

The rhizome contains an oil known as galangol, which upon fractional distillation produces cineol (which has medicinal properties), pinene, and eugenol, among others.[10]

See also

- Galangal

- Lesser galangal

- Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

References

- Duke, James A.; Bogenschutz-Godwin, Mary Jo; duCellier, Judi; Peggy-Ann K. Duke (2002). Handbook of Medicinal Herbs (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-8493-1284-7. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- K. V., Peter, ed. (2012). Handbook of Herbs and Spices. Volume 2 (2nd Edition) ed.). Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 9781845697341.

- Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen (2013). "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress". Oceanic Linguistics. 52 (2): 493–523. doi:10.1353/ol.2013.0016.

- Kays, Stanley J. (2011). Cultivated Vegetables of the World: A Multilingual Onomasticon. Wageningen Academic Publishers. p. 60. ISBN 9789086861644.

- Hoogervorst, Tom (2013). "If Only Plants Could talk...: Reconstructing Pre-Modern Biological Translocations in the Indian Ocean" (PDF). In Chandra, Satish; Prabha Ray, Himanshu (eds.). The Sea, Identity and History: From the Bay of Bengal to the South China Sea. Manohar. pp. 67–92. ISBN 9788173049866.

- Ravindran, P.N.; Pillai, Geetha S.; Babu, K. Nirmal (2004). "Under-utilized herbs and spices". In Peter, K.V. (ed.). Handbook of Herbs and Spices. Volume 2. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 9781855737211.

- Cheng, Lancini Jen-Hao (2014). Taxonomies of Taiwanese Aboriginal Musical Instruments (PDF) (PhD). University of Otago.

- Al-Adhroey, Abdulelah H.; Nor, Zurainee M.; Al-Mekhlafi, Hesham M.; Mahmud, Rohela (2010). "Median Lethal Dose, Antimalarial Activity, Phytochemical Screening and Radical Scavenging of Methanolic Languas galanga Rhizome Extract". Molecules. 15 (11): 8366–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.410.4830. doi:10.3390/molecules15118366. PMID 21081857.

- Kaur, A; Singh, R; Dey, CS; Sharma, SS; Bhutani, KK; Singh, IP (2010). "Antileishmanial phenylpropanoids from Alpinia galanga (Linn.) Willd". Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 48 (3): 314–7. PMID 21046987.

- Rasadah Mat Ali; Zainon Abu Samah; Nik Musaadah Mustapha; Norhara Hussein (2010). ASEAN Herbal and Medicinal Plants (PDF). Association of Southeast Asian Nations. p. 29. ISBN 978-979-3496-92-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2017.

Further reading

- Greater galangal

- Scheffer, J.J.C. & Jansen, P.C.M., 1999. Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd.[Internet] Record from Proseabase. de Guzman, C.C. and Siemonsma, J.S. (Editors). PROSEA (Plant Resources of South-East Asia) Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Alpinia galanga |

- Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd. Medicinal Plant Images Database (School of Chinese Medicine, Hong Kong Baptist University) (in Chinese) (in English)