Land grabbing

Land grabbing is the contentious issue of large-scale land acquisitions: the buying or leasing of large pieces of land by domestic and transnational companies, governments, and individuals. While used broadly throughout history, land grabbing as used in the 21st century primarily refers to large-scale land acquisitions following the 2007–08 world food price crisis.[1] Obtaining water resources is usually critical to the land acquisitions, so it has also led to an associated trend of water grabbing.[2] By prompting food security fears within the developed world and new found economic opportunities for agricultural investors, the food price crisis caused a dramatic spike in large-scale agricultural investments, primarily foreign, in the Global South for the purpose of industrial food and biofuels production. Although hailed by investors, economists and some developing countries as a new pathway towards agricultural development, investment in land in the 21st century has been criticized by some non-governmental organizations and commentators as having a negative impact on local communities. International law is implicated when attempting to regulate these transactions.[3]

Definition

The term "land grabbing" is defined as very large-scale land acquisitions, either buying or leasing. The size of the land deal is multiples of 1,000 square kilometres (390 sq mi) or 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) and thus much larger than in the past.[4] The term is itself controversial. In 2011, Borras, Hall and others wrote that "the phrase 'global land grab' has become a catch-all to describe and analyze the current trend towards large scale (trans)national commercial land transactions."[1] Ruth Hall wrote elsewhere that the "term 'land grabbing', while effective as activist terminology, obscures vast differences in the legality, structure, and outcomes of commercial land deals and deflects attention from the roles of domestic elites and governments as partners, intermediaries, and beneficiaries."[5]

In Portuguese, Land Grabbing is translated as "grilagem": "Much is said about grilagem and the term may be curious ... document aged by the action of insects [6] ... However, for those who live in the interior of the country, the expression effectively reveals a dark, heavy, violent meaning, involving abuses and arbitrary actions against the former occupants, occasionally with forced loss of possession by the taking of land " [7] The term grilagem applies to irregular procedures and / or illegal private landholding with violence in the countryside, exploitation of wealth, environmental damage and the threat to sovereignty[8], given their gigantic proportions.

Situation in the 21st century

Land Area

The Overseas Development Institute reported in January 2013, that with limited data available in general and existing data associated with NGOs interested in generating media attention in particular, the scale of global land trade may have been exaggerated. They found the figures below provide a variety of estimates, all in the tens of millions of hectares.[9]

- The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) estimated in 2009 between 15 and 20 million hectares of farmland in developing countries had changed hands since 2006.[4]

- As of January 2013 the Land Portal’s Land Matrix data totalled 49 million hectares of deals globally, although only 26 million hectares of these are transnational.

- A 2011 World Bank report by Klaus Deininger reported 56 million hectares worldwide.[10]

- Friis & Reenberg (2012) reported in 2012 between 51 and 63 million hectares in Africa alone.

- The GRAIN database[11] published in January 2012, quantified 35 million hectares, although when stripping out more developed economies such as Australia, New Zealand, Poland, Russia, Ukraine and Romania, the amount in the GRAIN database reduces to 25 million hectares.[9]

- Between 1990 and 2011, in the West Bank (Palestine) 195 km2 of land was expropriated by Israel, without compensation for the local owners, and allocated to immigrants for new settlements and for the establishment of mostly large farms. Water for the local population became extremely sparse.[12] In 2016, as a part of a permanent process 300 acres of land were added.[13]

Most seem to arrive at a ballpark of 20-60 million hectares. Given that total global farmland takes up just over 4 billion hectares,[14] these acquisitions could equate to around 1 per cent of global farmland. However, in practice, land acquired may not have previously been used as farmland, it may be covered by forests, which also equate to about 4 billion hectares worldwide, so transnational land acquisitions may have a significant role in ongoing deforestation.[9]

The researchers thought that a sizeable number of deals remain questionable in terms of size and whether they have been finalised and implemented. The land database often relies on one or two media sources and may not track whether the investments take place, or whether the full quantity reported takes place. For example, a number of deals in the GRAIN database[11] appear to have stalled including -

- 1 million hectares taken between US firms Arc Cap and Nile Trading and Development Inc in Sudan

- A 400,000 hectare deal between China and Colombia that seems to have stalled

- The 325,000 hectare investment by Agrisol in Tanzania

- A 324,000 hectare purchase of land by the UAE in Pakistan

- A suspended 320,000 hectare purchase by Chinese investors in Argentina.[9]

The researchers claim these are only those that have been checked, and already amount to nearly 10 per cent of the GRAIN database transnational land acquisitions. Deals are reported that use the estimate of the full extent of land that the firm expects to use. For example,

- Indian investment in Tanzania is reported at 300,000 hectares, currently operating on just 1,000 hectares

- Olam International’s investment in Gabon reported at 300,000 hectares, currently operating on just 50,000

- Three investments amounting to 600,000 hectares in Liberia, with Equatorial Palm Oil’s deal reported at 169,000 hectares, despite their plans to reach just 50,000 by 2020.[9]

Land Value

The researchers found that in terms of value of transnational land acquisitions, it is even harder to come across figures. Media reports usually just give information on the area and not on the value of the land transaction. Investment estimates, rather than the price of purchase are occasionally given[9]

They found a number of reports in land databases are not acquisitions, but are long-term leases, where a fee is paid or a certain proportion of the produce goes to domestic markets. For example:[9]

- An Indian investment in Ethiopia, where price per hectare ranged from $1.20 to $8 per hectare per year on 311,000 hectares

- Indian investors paid $4 per hectare per year on 100,000 hectares.

- Prince Bandar Bin Sultan of Saudi Arabia was reported to be paying $125,000 per year for 105,000 hectares in South Sudan, less than $1 per year on a 25-year lease.

- A South Korean investor in Peru was reported to be paying $0.80 per hectare.

The estimated value has been calculated for IFPRI’s 2009 data to be 15 to 20 million hectares of farmland in developing countries, worth about $20 billion-$30 billion.[4]

Researchers discovered global investment funds are reported to have sizeable funds available for transnational land investments.

- One estimate suggests “$100 billion waiting to be invested by 120 investment groups” while already “Saudi Arabia has spent $800 million on overseas farms”.[15] In 2011, a farm consultancy HighQuest told Reuters “Private capital investment in farming in expected to more than double to around $5-$7 billion in the next couple of years from an estimated $2.5-$3 billion invested in the last couple of years”.[16]

There is significant uncertainty around the value of transnational land acquisitions, particularly given leasing arrangements. Given the quantity of land and the size of investment funds operating in the area, it is likely that the value will be in the tens of billions of dollars.[9]

Land destinations

Researchers used the Land Portal’s Land Matrix database of 49 billion hectares of land deals, and found that Asia is a big centre of activity with Indonesia and Malaysia counting for a quarter of international deals by hectares. India contributes a further 10 per cent of land deals. The majority of investment is in the production of palm oil and other biofuels.[9]

They determined that the Land Portal also reports investments made by investors within their home country and after stripping these out found only 26 million hectares of transnational land acquisitions which strips out a lot of the Asian investments. The largest destination countries include

- Brazil with 11 per cent by land area

- Sudan with 10 per cent

- Madagascar, the Philippines and Ethiopia with 8 per cent each

- Mozambique with 7 per cent

- Indonesia with 6 per cent.

They found the reason seems to be biofuels expansion with exceptions in Sudan and Ethiopia, which sees a trend towards growth of food from Middle Eastern and Indian investors. Represented in the media as the norm they seem to be more the exception.[9]

Land origins

The researchers found a mixed picture in terms of the origins of investors. According to the Land Portal, the United Kingdom is the biggest country of origin followed by the United States, India, the UAE, South Africa, Canada and Malaysia, with China a much smaller player. The GRAIN database[11] says:

- United States, the UAE and China all constitute around 12 per cent of deals

- India with 8 per cent

- Egypt and the UK with 6 per cent

- South Korea with 5 per cent

- South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Malaysia all with 4 per cent.

Both the Land Portal and the GRAIN database show that the UK and the US are major players in transnational land acquisitions. This is agribusiness firms, as well as investment funds, investing mostly in sugar cane, jatropha or palm oil. This trend has clearly been driven by the biofuels targets in the EU and US, and greater vertical integration in agribusiness in general.[9]

The smaller trend is the picture of Middle Eastern investors or State-backed Chinese investments. While the UAE has done some significant deals by size, some driven by food deals, with Saudi Arabia a smaller number, this is not the dominant trend. While this aspect of land trade has gathered lots of media attention, it is not by any means a comprehensive story.[9]

Other deals

Other estimates of the scope of land acquisition, published in September 2010 by the World Bank, showed that over 460,000 square kilometres (180,000 sq mi) or 46,000,000 hectares (110,000,000 acres) in large-scale farmland acquisitions or negotiations were announced between October 2008 and August 2009 alone, with two-thirds of demanded land concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa.[17] Of the World Bank’s 464 examined acquisitions, only 203 included land area in their reports, implying that the actual total land covered could more than double the World Bank’s reported 46 million ha. The most recent estimate of the scale, based on evidence presented in April 2011 at an international conference convened by the Land Deal Politics Initiative, estimated the area of land deals at over 80 million ha.[18]

Of these deals, the median size is 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres), with one-quarter over 200,000 ha and one-quarter under 10,000 ha.[17] 37% of projects deal with food crops, 21% with cash crops, and 21% with biofuels.[17] This points to the vast diversity of investors and projects involved with land acquisitions: the land sizes, crop types, and investors involved vary wildly between agreements. Of these projects, 30% were still in an exploratory stage, with 70% approved but in varying stages of development. 18% had not started yet, 30% were in initial development stages, and 21% had started farming.[17] The strikingly low proportion of projects that had initiated farming signifies the difficulties inherent in large-scale agricultural production in the developing world.

Investment in land often takes the form of long-term leases, as opposed to outright purchases, of land. These leases often range between 25 and 99 years.[17] Such leases are usually undertaken between national or district governments and investors. Because the majority of land in Africa is categorized as “non-private" as a result of government policies on public land ownership and a lack of active titling, governments own or control most of the land that is available for purchase or lease.[19] Purchases are much less common than leases due to a number of countries’ constitutional bans on outright sales of land to foreigners.

The methods surrounding the negotiation, approval, and follow-up of contracts between investors and governments have attracted significant criticism for their opacity and complexity. The negotiation and approval processes have been closed in most cases, with little public disclosure both during and after the finalization of a deal. The approval process, in particular, can be cumbersome: It varies from approval by a simple district-level office to approval by multiple national-level government offices and is very subjective and discretionary.[17] In Ethiopia, companies must first obtain an investment license from the central government, identify appropriate land on the district level and negotiate with local leaders, then develop a contract with the regional investment office. Afterwards, the government will undertake a project feasibility study and capital verification process, and finally a lease agreement will be signed and land will be transferred to the investor.[20] In Tanzania, even though the Tanzania Investment Centre facilitates investments, an investor must obtain approval from the TIC, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Lands and Housing Development, and the Ministry of Environment, among which communication is oftentimes intermittent.[20]

Target countries

One common thread among governments has been the theme of development: Target governments tout the benefits of agricultural development, job creation, cash crop production, and infrastructure provision as drivers towards economic development and eventually modernization. Many companies have promised to build irrigation, roads, and in some cases hospitals and schools to carry out their investment projects. In return for a below-market-rate $10/ha annual payment for land, Saudi Star promised "to bring clinics, schools, better roads and electricity supplies to Gambella.”[21] Governments also count new job creation as a significant feature of land acquisitions.

The issue of agricultural development is a significant driving factor, within the larger umbrella of development, in target governments' agreement to investment by outsiders. The Ethiopian government's acceptance of cash crop-based land acquisitions reflects its belief that switching to cash crop production would be even more beneficial for food security than having local farmers produce crops by themselves.[22] Implicit in the characterization of African agriculture as "underdeveloped" is the rejection of local communities' traditional methods of harvesting as an inadequate form of food production.

On a smaller scale, some deals can be traced to a personal stake in the project or possibly due to corruption or rent-seeking. Given the ad hoc, decentralized, and unorganized approval processes across countries for such transactions, the potential for lapses in governance and openings for corruption are extremely high. In many countries, the World Bank has noted that investors are often better off learning how to navigate the bureaucracies and potentially pay off corrupt officers of governments rather than developing viable, sustainable business plans.[17]

Responses

Since 2010 Brazil enforces in a stricter way a long-existing law that limits the size of farmland properties foreigners may purchase, having halted a large part of projected foreign land purchases.[23]

In Argentina, as of September 2011, a projected law is discussed in parliament that would restrict the size of land foreign entities can acquire to 1000 hectare.[24]

Types of land investment

Investors can be generally broken down into three types: agribusinesses, governments, and speculative investors. Governments and companies in Gulf States have been very prominent along with East Asian companies. Many European- and American-owned investment vehicles and agricultural producers have initiated investments as well. These actors have been motivated by a number of factors, including cheap land, potential for improving agricultural production, and rising food and biofuel prices. Building on these motivations, investments can be broken down into three main categories: food, biofuel, and speculative investment. Forestry also contributes to a significant amount of large-scale land acquisition, as do several other processes: Zoomers[25] mentions drivers such as the creation of protected areas and nature reserves, residential migration, large-scale tourist complexes and the creation of Special Economic Zones, particularly in Asian countries.

Food

Food-driven investments, which comprise roughly 37% of land investments worldwide, are undertaken primarily by two sets of actors: agribusinesses trying to expand their holdings and react to market incentives, and government-backed investments, especially from the Gulf states, as a result of fears surrounding national food security.[17]

Agricultural sector companies most often view investment in land as an opportunity to leverage their significant monetary resources and market access to take advantage of underused land, diversify their holdings, and vertically integrate their production systems. The World Bank identifies three areas in which multinational companies can leverage economies of scale: access to cheap international rather than domestic financial markets, risk-reducing diversification of holdings, and greater ability to address infrastructural roadblocks.[17] In the past few decades, multinationals have shied away from direct involvement in relatively unprofitable primary production, instead focusing on inputs and processing and distribution.[26] When the food price crisis hit, risk was transferred from primary production to the price-sensitive processing and distribution fields, and returns became concentrated in primary production. This has incentivized agribusinesses to vertically integrate to reduce supplier risk that has been heightened by the ongoing food price volatility.[20] These companies hold mixed attitudes towards food imports and exports: While some concentrate on food exports, others focus on domestic markets first.

While company-originated investments have originated from a wide range of countries, government-backed investments have originated primarily from the food-insecure Gulf States. Examples of such government-backed investments include the government of Qatar’s attempt to secure land in the Tana River Delta and the Saudi government's King Abdullah Initiative.[27][28] Additionally, sovereign wealth funds acting as the investments arms of governments have initiated a number of agreements in Sub-Saharan Africa. Since the population of the Gulf states is set to double from 30 million in 2000 to 60 million in 2030, their reliance on food imports is set to increase from the current level of 60% of consumption.[29] The director general of the Arab Organisation for Agricultural Development echoed the sentiment of many Gulf leaders in proclaiming, “the whole Arab World needs of cereal, sugar, fodder and other essential foodstuffs could be met by Sudan alone.”[20]

Biofuels

Biofuel production, currently comprising 21% of total land investments, has played a significant, if at times unclear, role. The use and popularity of biofuels has grown over the past decade, corresponding with rising oil prices and increased environmental awareness. The total area under biofuel crops more than doubled between 2004 and 2008, expanding to 36 million ha by 2008.[30] This rise in popularity culminated in EU Directive 2009/28/EC in April 2009, which set 10% mandatory targets for renewable energy use, primarily biofuels, out of the total consumption of fuel for transport, by 2020.[31] Taken as a whole, the rise in biofuels popularity, while perhaps beneficial for the environment, sparked a chain reaction by making biofuels production a more attractive option than food production and drawing land away from food to biofuel production.

The effect of the rise in popularity in biofuels was two-fold: first, demand for land for biofuel production became a primary driver of land sales in Sub-Saharan Africa; second, demand for biofuels production crowded out supply of traditional food crops worldwide. By crowding out food crops and forcing conversion of existing food-producing land to biofuels, biofuels production had a direct impact on the food supply/demand balance and consequently the food price crisis. One researcher from the IFPRI estimated that biofuels had accounted for 30 percent of the increase in weighted average grain prices.[32]

Criticism

Large-scale investments in land since 2007 have been scrutinized by civil society organizations, researchers, and other organizations because of issues such as land insecurity, local consultation and compensation for land, displacement of local peoples, employment of local people, the process of negotiations between investors and governments, and the environmental consequences of large-scale agriculture. These issues have contributed to critics' characterization of much large-scale investment since 2007 as "land grabbing," irrespective of differences in the types of investments and the ultimate impact that investments have on local populations.[5]

Land insecurity

One of the major issues is land tenure: In a 2003 study, the World Bank estimated that only between 2 and 10 percent of total land in Africa is formally tenured.[20] Much of the lack of private ownership is due to government ownership of land as a function of national policy, and also because of complicated procedures for registration of land and a perception by communities that customary systems are sufficient.[20] World Bank researchers have found that there existed a strong negative statistical link between land tenure recognition and prospective land acquisitions, with a smaller yet still significant relationship for implemented projects as well.[17] They concluded that “lower recognition of land rights increased a country’s attractiveness for land acquisition,” implying that companies have actively sought out areas with low land recognition rights for investment.[17]

Local consultation and compensation

While commonly required by law in many host countries, the consultation process between investors and local populations have been criticized for not adequately informing communities of their rights, negotiating powers, and entitlements within land transactions.[33]

Consultations have been found extremely problematic due to the fact that they often reach just village chiefs but neglect common villagers and disenfranchised groups. World Bank researchers noted that “a key finding from case studies is that communities were rarely aware of their rights and, even in cases where they were, lacked the ability to interact with investors or to explore ways to use their land more productively.”[17] When consultations were even conducted, they often did not produce written agreements and were found to be superficial, glossing over environmental and social issues.[17] In Ghana and elsewhere, chiefs often negotiated directly with investors without the input from other villagers, taking it upon themselves to sell common land or village land on their own.[17] Moreover, investors often had obtained approval for their projects before beginning consultations, and lacked any contractual obligation to carry out promises made to villagers.[17]

There is a knowledge gap between investors and local populations regarding the land acquisition process, the legal enforceability of promises made by investors, and other issues. The inability of villagers to see and study the laws and regulations around land sales severely deteriorates communities’ agency in consultations. When consultations do occur with communities, some take place in spans of only two to three months, casting doubt on whether such short time frames can be considered as adequate consultation for such large, wide-reaching, and impactful events.[27]

An additional concern with consultations is that women and underrepresented populations are often left outside during the process. Large-scale projects in Mozambique rarely included women in consultations and never presented official reports and documents for authorization by women.[34] This holds true when women are the primary workers on the land that is to be leased out to companies.[35] Meanwhile, pastoralists and internally displaced people were oftentimes intentionally excluded from negotiations, as investors tried to delegitimize their claims on land.[17] This led to a lack of awareness on the part of these vulnerable groups until lease agreements have already been signed to transfer land. This oversight in consultations further disenfranchises previously overlooked communities and worsens power inequities in local villages.

Displacement

Another criticism of investment in land is the potential for large-scale displacement of local people without adequate compensation, in either land or money. These displacements often result in resettlement in marginal lands, loss of livelihoods especially in the case of pastoralists, gender-specific erosion of social networks. Villagers were most often compensated as according to national guidelines for loss of land, loss of improvements over time on the land, and sometimes future harvests.[20] However, compensation guidelines vary significantly between countries and depending on the types of projects undertaken. One study by the IIED concluded that guidelines for compensation given to displaced villagers in Ethiopia and Ghana was insufficient to restore livelihoods lost through dislocation.[20]

There are a number of issues with the process of relocating locals to other areas where land is less fertile. In the process of relocation, often changed or lost are historical methods of farming, existing social ties, sources of income, and livelihoods. This holds drastic impacts especially in the case of women, who rely greatly upon such informal relationships.[36]

Employment

When not displaced, the conversion of local farmers into laborers holds numerous negative consequences for local populations. Most deals are based on the eventual formation of plantation-style farming, whereupon the investing company will own the land and employ locals as laborers in large-scale agricultural plots. The number of jobs created varies greatly dependent on commodity type and style of farming planned.[17] In spite of this volatility, guarantees of job creation are rarely, if ever, addressed in contracts. This fact, combined with the intrinsic incentives towards mechanization in plantation-style production, can lead to much lower employment than originally planned for. When employed, locals are often paid little: In investments by Karuturi Global in Ethiopia, workers are paid on average under $2 a day, with a minimum wage of 8 birr, or $0.48, per day, both of which are under the World Bank poverty limit of $2 per day.[37]

Government negotiations

In addition to the lack of coordination between ministries, there is a wide knowledge gap between government-level offices and investors, leading to a rushed and superficial investment review. Many government agencies initially overwhelmed by the deluge of investment proposals failed to properly screen out non-viable proposals.[17] Due to the knowledge gaps between government agencies and investors, “in most countries it is implicitly presumed that investors will have the right incentive and be the best qualified to assess economic viability,” leading to a lack of reporting requirements or monitoring arrangements, key information on land uses and value of the investment, and checks on economic viability.[17] The Sudanese government has been noted as having paid minimal attention to existing land rights and neglecting to conduct any economic analysis on potential projects.[17] In addition, many countries, including Cambodia, Congo, Sudan, and Ghana, have neglected to catalog and file even general geographical descriptions of land allocation boundaries.[17]

One addition to many contracts between governments and investors is a Stabilisation Clause, which insulates investors from the effect of changed governmental regulations. Such clauses severely restrict the government’s ability to change any regulations that would have a negative economic impact on the investment.[20] While advantageous for businesses, these stabilization clauses would severely hinder the ability of governments to address possible social and/or environmental concerns that become apparent after the beginning of the project.

Environmental impact

Land investment has been criticized for its implicit endorsement of large-scale industrial agriculture, which relies heavily on costly machinery, fertilizers, pesticides, and other inputs, over smallholder agriculture.[38] As foreign investors begin to develop the land, they will, for the most part, start a shift towards large-scale agriculture to improve upon existing “unproductive” agricultural methods. The threat of the conversion of much of Africa’s land to such large-scale agriculture has provoked a severe pushback from many civil society organizations such as GRAIN, La Via Campesina, and other lobbyists for small-scale agriculture.[39]

Foreign investors, through large-scale agriculture, increase the effectiveness of underused resources of land, labor, and water, while further providing additional market connections, large-scale infrastructure development, and provision of seeds, fertilizers, and technology. Proposed increases in production quantity, as touted by investors and hosts, are exemplified by Ethiopia’s Abera Deressa, who claims that “foreign investors should help boost agricultural output by as much as 40%” throughout Ethiopia.[21] However, large-scale mechanized agricultural production often entails the use of fertilizers and intensive farming techniques that have been criticized by numerous civil society actors as extremely ecologically detrimental and environmentally harmful over the long run.[40][41] Over time, such intensive farming threatens to degrade the quality of topsoil and damage local waterways and ecosystems. As such, civil society actors have widely accused land investors for promoting “not agricultural development, much less rural development, but simply agribusiness development.”[41] This trend towards large-scale agriculture that overrides local knowledge and sustainable local farming runs directly counter to the recent IAASTD report, backed by the FAO, UNDP, World Bank, and others, that to increase food security over the long term, sustainable peasant agriculture must be encouraged and supported.[42]

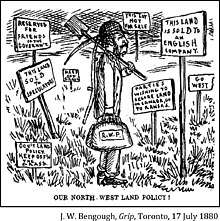

Neocolonialism

Foreign investment in land has been criticized by many civil society actors and individuals as a new realization of neocolonialism, signifying a renewed economic imperialism of developed over developing nations.[43] Critics have pointed to the acquisitions of large tracts of land for economic profit, with little perceived benefit for local populations or target nations as a whole, as a renewal of the economically exploitative practices of the colonial period.

Laws and Regulations Concerning Reporting of Foreign Investment in Land

A 2013 report found no available literature giving recommendations for how the UK could change its laws and regulations to require UK companies investing in land in developing countries to report relevant data.[44]

The researcher looks at a literature review by Global Witness, the Oakland Institute, and the International Land Coalition from 2012 which states that there is little sustained focus on the extraterritorial obligations of states over overseas business enterprises.[44][45]

The researcher found most available literature and policy on transparency in land investment focusing on:

- Facilitating community engagement in planning decisions and enhancing community rights

- Upgrading obligations/capacities of host governments to improve regulation of foreign-funded land deals.

- Developing international frameworks to improve transparency in land deals.[44]

He found this focus was confirmed by a range of other documents reviewing address international efforts to promote responsible investment in agriculture and recommended the International Working Group paper[46] and Smaller & Mann.[47] The researcher mentions a report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development stating a ‘significant lack of concrete and verifiable’ empirically-based policy and legal work on the issue of foreign investment in agricultural land[44][47]

The researcher saw Smaller and Mann[47] note that in many host states like the UK ‘there is either no, or insufficient or unclear domestic law concerning land rights, water rights, pollution controls for intensive agriculture, human health, worker protection and so on.[44]

The researcher did find that international law framework provides hard rights for foreign investors with two primary sources of international law relating to this issue: international contracts, which are commercial in nature; and international treaty law on investment, with both bodies acting on a commercial perspective and focusing on economic interests of foreign investors, rather than social or environmental dimensions[44][47]

He discussed the UN’s Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights[48] which address the extraterritorial obligations of states over overseas business enterprises and finds the principles do not provide any detailed discussion of the UK case, or of timeframes and costs.[44]

Extraterritorial obligations of states over overseas businesses

The researcher studied a report by Global Witness, the Oakland Institute and the International Land Coalition which identifies four key entry points for improving transparency in large-scale land acquisition:[45]

- transparent land and natural resource planning;

- free, prior and ‘informed’ consent;

- public disclosure of all contractual documentation;

- multi-stakeholder initiatives, independent oversight and grievance mechanisms’

- a range of additional entry points for future policy work and campaigning, which includes addressing the ‘extra-territorial obligations of states over overseas business enterprises’.[44]

He found the report stresses that ‘further analysis is needed to identify the benefits and opportunities of each entry point, as well as potential limitations, challenges, and risks around future campaigns which would need to be addressed from the start’ and notes that as of early 2013 there is a gap between the extent to which individual states fulfill their obligations to regulate businesses overseas, and ‘the extent to which such regulations cover transparency and information disclosure’[44][49]

The researcher found that the UN’s Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, written by the former UN Special Representative to the Secretary General for Business and Human Rights, Professor John Ruggie[48] provide some discussion of how business enterprises need to undertake human rights due diligence suggesting that states ‘should set out clearly the expectation that all business enterprises domiciled in their territory and/or jurisdiction respect human rights throughout their operations’ and notes that ‘at present States are not generally required under international human rights law to regulate the extraterritorial activities of businesses domiciled in their territory and/or jurisdiction.[44]

He claims that they are not generally prohibited from doing so either, provided there is a recognised jurisdictional basis’[48] and says the report notes that some states have introduced domestic measures with extraterritorial implications. ‘Examples include requirements on “parent” companies to report on the global operations of the entire enterprise; multilateral soft-law instruments such as the Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; and performance standards required by institutions that support overseas investments.[44]

The researcher found other approaches amount to direct extraterritorial legislation and enforcement including criminal regimes that allow for prosecutions based on the nationality of the perpetrator no matter where the offence occurs’[44][48]

He read that the UN’s Guiding Principles[48] propose that ‘contracts should always be publicly disclosed when the public interest is impacted; namely cases where the project presents either large-scale or significant social, economic, or environmental risks or opportunities, or involves the depletion of renewable or non-renewable natural resources’[44][49]

He found Global Witness et al.[45] state that governments and businesses often claim that confidentiality is necessarily to protect commercially sensitive information contained in investment contracts.[44]

Other relevant international Principles, Guidelines and Instruments

The researcher states that the Global Witness et al. paper[49] details a number of international instruments that ‘create obligations and responsibilities throughout all stages of decision-making around large-scale land investments’, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[44]

He found several thematic binding agreements also examined in the report: the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity and the 1994 Convention to Combat Desertification.[44]

The UK encourages companies to abide by OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises which provide voluntary principles and standards for responsible business conduct for multinational corporations operating in or from countries adhering to the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises, including detailed guidance concerning information disclosure.[50] However they do not, provide any specific recommendations on land.[44]

The researcher read the Global Witness et al.[45] report also finds that ‘a number of instruments offer companies the opportunity to associate themselves with a set of principles or goals that demonstrate corporate social responsibility’ but most of these are largely ‘declarative’.[44]

Overall, he summaries that the report notes that although these various instruments ‘recognise secrecy and lack of access to information to be a problem, they give almost no detail as to how it should be tackled in practice, nor do any mandatory provisions yet exist to ensure such an implicit aspiration is met’[44][49]

Information issues

In a joint research project between the FAO, IIED, and IFAD, Cotula et al. found that the majority of host countries lacked basic data on the size, nature, and location of land acquisitions through land registries or other public sources, and that “researchers needed to make multiple contacts…to access even superficial and incomplete information.”[20] The World Bank’s own lack of land size information on over half of the reported land grabs that it researched points to the difficulties inherent in gaining access to and researching individual land acquisitions.[17]

The European project EJOLT (Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade) is building a global map of land grabbing, with the aim to make an interactive online map on this and many other environmental justice issue by 2013. The project also produces in-depth resources on land grabbing, such as this video on land grabbing in Ethiopia.

Notable cases

In Madagascar, the anger among the population about land sales led to violent protests. The South Korean corporation Daewoo was in the process of negotiations with the Malagasy government for the purchase of 1.3 million hectares, half of all agricultural land, to produce corn and palm oil. This investment, while one of many pursued in Madagascar, attracted considerable attention there and led to protests against the government.[51]

In Sudan, numerous large-scale land acquisitions have taken place in spite of the country's unresolved political and security situation. One of the most prominent, involving a former GRAPE partner named Phil Heilberg, garnered attention by playing in Rolling Stone. Heilberg, who is planning to invest in 800,000 ha of land in partnership with many of Sudan's top civilian officials, attracted criticism with his remarks (regarding Africa and land grabbing) that "the whole place is like one big sewer — and I'm like a plumber."[52]

In Myanmar, a 2018 amendment to the 2012 Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law has affects for millions of rural peoples, requiring registration of land and private land ownership. Failure to register land can result in criminal punishments for remaining on that land. The new amendment heavily affects ethnic areas and internally displaced peoples. Unregistered land has been claimed by or sold to private agribusiness ventures. [53][54]

List of land grabbings of EU countries

List of land grabbings in hectares of involved EU countries in non-EU countries according to EU Land Matrix Data of 2016.[55]

- 1. United Kingdom (1 972 010)

- 2. France (629 953)

- 3. Italy (615 674)

- 4. Finland (566 559)

- 5. Portugal (503 953)

- 6. Netherlands (414 974)

- 7. Germany (309 566)

- 8. Belgium (251 808)

- 9. Luxembourg (157 914)

- 10. Spain (136 504)

- 11. Romania (130 000)

- 12. Sweden (77 329)

- 13. Denmark (31 460)

- 14. Austria (21 000)

- 15. Estonia (18 800)

See also

- Agribusiness

- Agriculture

- Biofuel

- Economic development

- Food security

- Food sovereignty

- Illegal construction

- Industrial agriculture

- Land rights

- Land titling

- Sustainable agriculture

- 2007-2008 world food price crisis

- Water grabbing

- Sustainable development

- Water right

- Chinese land grabbing

References

- Borras Jr., Saturnino M.; Ruth Hall; Ian Scoones; Ben White; Wendy Wolford (24 March 2011). "Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: an editorial introduction". Journal of Peasant Studies. 38 (2): 209. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.559005.

- Maria Cristina Rullia, Antonio Savioria, and Paolo D’Odorico, Global Land and Water Grabbing, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 3 (2013): 892–97.

- Lea Brilmayer and William J. Moon, Regulating Land Grabs: Third Party States, Social Activism, and International Law, book chapter in Rethinking Food Systems, February 2014

- "Outsourcing's third wave". The Economist. 23 May 2009.

- Hall, Ruth (June 2011). "Land grabbing in Southern Africa: the many faces of the investor rush". Review of African Political Economy. 38 (128): 193–214. doi:10.1080/03056244.2011.582753.

- "Rogério Reis Devisate - Grilagem de Terras e da Soberania". rogerioreisdevisate. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- "Rogério Reis Devisate - Grilagem de Terras e da Soberania". rogerioreisdevisate. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- "Rogério Reis Devisate - Grilagem de Terras e da Soberania". rogerioreisdevisate. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- "Transnational land acquisitions". Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Rising Global Interest in Farmland" (PDF). The World Bank. March 2015.,

- "GRAIN — GRAIN releases data set with over 400 global land grabs". www.grain.org. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Land Grab". B'Tselem. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Silver, Charlotte (30 March 2016). "Israel's West Bank land grabs biggest in decades". electronicintifada.net. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Byerlee, Derek and Deininger, Klaus (2011), Rising Global Interest in Farmland, The World Bank

- http://www.westerninvestor.com/index.php/news/55-features/764-land-values Archived 2013-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Farm private investment seen doubling in two years - Alberta Farmer Express". www.albertafarmexpress.ca. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Deininger, Klaus; Derek Byerlee (2010). Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can it Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits? (PDF). The World Bank.

- Borras, Jun; Ian Scoones; David Hughes (15 April 2011). "Small-scale farmers increasingly at risk from 'global land grabbing'". The Guardian.co.uk: Poverty Matters Blog. London. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Borras, Saturnino; Jennifer Franco (16 December 2010). "Regulating land grabbing?". Pambazuka News. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- Cotula, Lorenzo; Sonja Vermeulen; Rebeca Leonard; James Keeley (2009). Land grab or development opportunity? Agricultural investment and international land deals in Africa (PDF). London/Rome: FAO, IIED, IFAD.

- Butler, Ed (16 December 2010). "Land grab fears for Ethiopian rural communities". BBC World Service. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Davison, William (26 October 2010). "Ethiopia Plans to Rent Out Belgium-Sized Land Area to Produce Cash Crops". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- "Farmland Investment". Peer Voss, a farmland brokerage. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

restrictions now limiting the size of farm land...

- "Farmland Investment". Peer Voss, a farmland brokerage. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

discussed in congress that would limit the maximum...

- Zoomers, A. (2010) ‘Globalization and the foreignization of space: The seven processes driving the current global land grab’. Journal of Peasant Studies. 37:2, 429-447.

- Selby, A. (2009). Institutional Investment into Agricultural Activities: Potential Benefits and Pitfalls. Washington D.C.: Presented at the conference "Land Governance in support of the MDGs: responding to New Challenges," World Bank.

- Cotula, Lorenzo (2011). The outlook on farmland acquisitions. International Land Coalition, IIED.

- Land grabbing in Kenya and Mozambique. FIAN. 2010.

- Woertz, E. (4 March 2009). "Gulf food security needs delicate diplomacy". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Towards sustainable production and use of resources assessing biofuels. Paris: United Nations Environment Programme. 2009.

- Graham, Alison; Sylvain Aubry; Rolf Künnemann; Sofia Suarez (2010). The Impact of Europe's Policies and Practices on African Agriculture and Food Security. FIAN. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- Rosegrant, Mark (2008). Biofuels and Grain Prices: Impacts and Policy Responses. Testimony for US Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

- Pearce, F. (2012). The land grabbers: The new fight over who owns the Earth. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Nhantumbo, I.; A. Salomao (2010). Biofuels, land access and rural livelihoods in Mozambique (PDF). London: IIED.

- Duvane, L (2010). Mozambique Case Study. Cape Town: 2010 Institute for Poverty Land and Agrarian Studies: Regional Workshop on Commercialization of Land in Southern Africa.

- Behrman, Julia; Ruth Meinzen-Dick; Agnes Quisumbing (2011). The Gender Implications of Large-Scale Land Deals (PDF). IFPRI.

- McLure, Jason (30 December 2009). "Ethiopian Farms Lure Investor Funds as Workers Live in Poverty". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Twenty-First-Century Land Grabs (November 2013), Fred Magdoff, Monthly Review, Volume 65, Issue 06

- "Stop Land Grabbing Now!" (PDF). FIAN, LRAN, GRAIN. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Balehegn, Mulubrhan (2015-03-04). "Unintended Consequences: The Ecological Repercussions of Land Grabbing in Sub-Saharan Africa". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 57 (2): 4–21. doi:10.1080/00139157.2015.1001687. ISSN 0013-9157.

- "Seized: The 2008 land grab for food and financial security". GRAIN. 24 October 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Agriculture at Crossroads: International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development, Science, and Technology. IAASTD. 2008.

- Vidal, John (3 July 2009). "Fears for the world's poor countries as the rich grab land to grow food". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Walton, O., 2013, Laws and Regulations Concerning Reporting of Foreign Investment in Land, Economic and Private Sector Professional Evidence And Applied Knowledge Services

- Global Witness, Oakland Institute, International Land Coalition, 2012, Dealing with Disclosure: Improving Transparency in Decision-Making over Large Scale Land Acquisitions, Allocations and Investments

- International Working Group on the Food Security Pillar of the G20 Multi-Year Action Plan on Development (2011) ‘Options for Promoting Responsible Investment in Agriculture’, Report to the High-Level Development Working Group http://archive.unctad.org/sections/dite_dir/docs//diae_dir_2011-06_G20_en.pdf

- "A Thirst for Distant Lands: Foreign investment in agricultural land and water" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Report of the Special Representative of the SecretaryGeneral on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, John Ruggie" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- http://www.globalwitness.org/sites/default/files/library/Dealing_with_disclosure_1.pdf Archived 2012-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2011 Edition" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Land Grabbing: the End of Sustainable Agriculture?".

- Funk, McKenzie (27 May 2010). "Meet the New Capitalists of Chaos" (PDF). Rolling Stone. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ""A Declaration of War on Us": The 2018 VFV Law Amendment and its Impact on Ethnic Nationalities". Transnational Institute. 2018-12-13. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- shwe yone, IDP Voice 5min# VFV Law#2018, retrieved 2019-01-25

- "Land grabbing and human rights: The involvement of European corporal and financial entities in land grabbing outside the European Union" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-12-20.

External links

- Land Grabbing or Land to Investors?, Alfredo Bini photojournalist. See also the documentary: Land Grabbing or Land to Investors?

- The Truth About Land Grabs, Oxfam America. See also: About GROW, Oxfam

- Transnational Institute, Global Land Grab: A primer

- Farm Land Grab.org

- World Bank, FAO, UNDP, Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment that respects rights, livelihoods and resources

- Food Crisis and the Global Land Grab website

- World Bank, Global Food Crisis resource page

- Seized! The 2008 Land Grab for Food and Financial Security, Monthly Review Magazine (MRzine)

- Twenty-First-Century Land Grabs (November 2013), Fred Magdoff, Monthly Review, Volume 65, Issue 06

- Illustration - Who is buying the earth?, Katapult-Magazine (14.03.2015)