Laguna de Bay

Laguna de Báý (Filipino: Lawa ng Báé IPA: [baɪ]; English: Lake of Báý) or Laguna Lake is the largest lake in the Philippines. It is located east of Metro Manila, between the provinces of Laguna to the south and Rizal to the north. A freshwater lake, it has a surface area of 911–949 km² (352–366 sq mi), with an average depth of about 2.8 metres (9 ft 2 in) and an elevation of about 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) above sea level. The lake is shaped like a stylized 'W', with two peninsulas jutting out from the northern shore. Between these peninsulas, the middle lobe fills the large volcanic Laguna Caldera. In the middle of the lake is the large island of Talim, which falls under the jurisdiction of the towns of Binangonan and Cardona in Rizal province.

| Laguna de Báý | |

|---|---|

Landsat photo | |

.svg.png) Laguna de Báý Location within the Philippines | |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 14°23′00″N 121°15′00″E |

| Type | Caldera lake (theorized)/ Tectonic lake |

| Primary inflows | 21 tributaries |

| Primary outflows | Pasig River (via Napindan Channel) |

| Basin countries | Philippines |

| Max. length | 47.3 km (29.4 mi) (E-W) |

| Max. width | 40.5 km (25.2 mi) (N-S) |

| Surface area | 911–949 km² (352–366 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) |

| Max. depth | 20 m (66 ft) (Diablo pass) |

| Shore length1 | 285 km (177 mi) |

| Surface elevation | less 2 m (6 ft 7 in) |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

The lake is one of the primary sources of freshwater fish in the country. Its water drains to Manila Bay via the Pasig River.

Etymology

Laguna de Bay means "Lagoon of [the town of] Bay" for the lakeshore town of Bay (pronounced as "Bä'ï"), the former provincial capital of Laguna province.[1] Alternate spellings of the town's name include "Bae" or "Ba-i", and in the early colonial times, "Bayi" or "Vahi". Thus, the lake is sometimes spelled as "Laguna de Bae" or "Laguna de Ba-i", mostly by the locals.[1] The town's name is believed to have come from the Tagalog word for "settlement" (bahayan), and is related to the words for "house" (bahay), "shore" (baybayin), and "boundary" (baybay), among others. The introduction of the English language during the American occupation of the Philippines, elicited confusion as the English word "bay", referring to another body of water, was mistakenly substituted to the town name that led to its mispronunciation.[1] However, the word "Bay" in Laguna de Bay has always referred to the town.[2]

The Spanish word Laguna refers to not just lagoons but also for freshwater lakes, aside from lago.[3] Some examples of the worldwide usage of laguna for lakes include Laguna Chicabal in Guatemala, Laguna de Gallocanta in Spain, Laguna Catemaco in Mexico and Laguna de Leche, the largest lake in Cuba. The lake's alternate name, "Laguna Lake", refers to the Province of Laguna, the province at the southern shore of the lake. Laguna province, though, was named because of the large lake and was originally called La Laguna till the early 20th century.[4]

In the pre-Hispanic era, the lake was known as "Puliran Kasumuran" (Laguna Copperplate Inscription, c. 900 AD), and later by "Pulilan" (Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, 1613. Pila, Laguna).

Currently, the lake is often incorrectly called "Laguna Bay," including in government websites, or "Laguna Lake" which is used by the Laguna Lake Development Authority.[5]

Geography

The middle part of Laguna de Bay between Mount Sembrano and Talim Island, is the Laguna Caldera believed to have been formed by two major volcanic eruptions, around 1 million and 27,000–29,000 years ago. Remnants of its volcanic history are shown by the presence of series of maars around the area of Tadlac Lake and Mayondon hill in Los Baños, Laguna,[6] another maar at the southern end of Talim Island, and a solfataric field in Jala Jala.[7]

Laguna de Bay is a large shallow freshwater body in the heart of Luzon Island with an aggregate area of about 911 km2 (352 sq mi) and a shoreline of 220 km (140 mi).[8] It is considered to be the third largest inland body of water in Southeast Asia after Tonle Sap in Cambodia and Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia. Laguna de Bay is bordered by the province of Laguna in the east, west and southwest, the province of Rizal in the north to northeast, and Metropolitan Manila in the northwest. The lake has an average depth of 2.8 metres (9 ft 2 in) and its excess water is discharged through the Pasig River.[9][10]

The lake is fed by 45,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) of catchment areas and its 21 major tributaries. Among these are the Pagsanjan River which is the source of 35% of the Lake's water, the Santa Cruz River which is the source of 15% of the Lake's water, the Marikina River (through the Manggahan Floodway), the Mangangate River, the Tunasan River, the San Pedro River, the Cabuyao River, the San Cristobal River, the San Juan River, the Bay, Calo and Maitem rivers in Bay, the Molawin, Dampalit and Pele rivers in Los Baños, the Pangil River, the Tanay River, the Morong River, the Siniloan River and the Sapang Baho River.[8] [11]

Uses

The lake is a multipurpose resource. In order to reduce the flooding in Manila along the Pasig River, during heavy rains, the peak water flows of the Marikina River are diverted via the Manggahan Floodway to Laguna de Bay, which serves as a temporary reservoir. In case the water level on the lake is higher than the Marikina River, the flow on the floodway is reversed, both Marikina River and the lake drain through Pasig River to Manila Bay.[12]

The lake has been used as a navigation lane for passenger boats since the Spanish colonial era. It is also used as a source of water for the Kalayaan Pumped-Storage Hydroelectric Project in Kalayaan, Laguna. Other uses include fishery, aquaculture, recreation, food support for the growing duck industry, irrigation and a "virtual" cistern for domestic, agricultural, and industrial effluents.[9] Because of its importance in the development of the Laguna de Bay Region, unlike other lakes in the country, its water quality and general condition are closely monitored.[13] This important water resource has been greatly affected by development pressures like population growth, rapid industrialization, and resources allocation.[14]

Known lake islands include Talim, the largest and most populated island on the lake;[15] Calamba Island, which is completely occupied by the Wonder Island resort in Calamba, Laguna;[15] Cielito Lindo, a privately owned island off the coast of mainland Cardona, Rizal;[15][16] Malahi Island which used to be the site of Maligi Island military reservation, near the southern tip of Talim;[15][15][17] the nearby islands of Bonga and Pihan, also in Cardona; and Bay Island off the coast of Bay, Laguna, which is closely associated with the precolonial crocodile-deity myths of that town.

Environmental issues

At least 18 fish species are known from Laguna de Bay; none are strictly endemic to the lake, but 3 are endemic to the Philippines: Gobiopterus lacustris, Leiopotherapon plumbeus and Zenarchopterus philippinus.[18] Aquaculture is widespread in Laguna de Bay, but often involves non-native species.[19] Some of these have escaped and have become invasive species, representing a threat to the native fish.[20]

Because of the problems facing and threatening the potential of the lake, then President Ferdinand Marcos signed into law Republic Act (RA) 4850 in 1966 creating the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA), the main agency tasked to oversee the programs that aimed to develop and protect Laguna de Bay.[21] Though it started as a mere quasi-government agency with regulatory and proprietary functions, its charter was strengthened by Presidential Decree (PD) 817 in 1975 and by Executive Order (EO) 927 in 1983 to include environmental protection and jurisdiction over the surface waters of the lake basin. In 1993, by virtue of the devolution, the administrative supervision of the LLDA was transferred to the DENR by EO 149.[22]

Government data showed that about 60% of the estimated 8.4 million people residing in the Laguna de Bay Region discharge their solid and liquid wastes indirectly to the lake through its tributaries. A large percentage of these wastes are mainly agricultural while the rest are either domestic or industrial[23] According to DENR (1997), domestic and industrial wastes contribute almost equally at 30% each. Meanwhile, agricultural wastes take up the remaining 40%. In a recent sensitivity waste load model ran by the Laguna Lake Development Authority's (LLDA) Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) division, it revealed that 70% of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) loadings came from households, 19% from industries, and 11% came from land run-off or erosion (LLDA, 2005).

As far as industries and factories are concerned, there are about 1,481 and increase is expected.[10] Of the said figure, about 695 have wastewater treatment facilities. Despite this, the lake is absorbing huge amounts of pollution from these industries in the forms of discharges of industrial cooling water, toxic spills from barges and transport operations, and hazardous chemicals like lead, mercury, aluminum and cyanide.[24] Based from the said figure, 65% are classified as “pollutive” industries.

The hastened agricultural modernization throughout the region took its toll on the lake. This paved the way for massive and intensified use of chemical based fertilizers and pesticides whose residues eventually find their way to the lake basin. These chemicals induce rapid algal growth in the area that depleted oxygen levels in the water. Hence, oxygen available to the lake is being used up thereby depleting the available oxygen for the fish, causing massive fish kills.[25]

As far as domestic wastes are concerned, around 10% of the 4,100 metric tons of waste generated by residents of Metro Manila are dumped into the lake, causing siltation of the lake. As reported by the now defunct Metropolitan Manila Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS), only 15% of the residents in the area have an effective waste disposal system. Moreover, around 85% of the families living along the shoreline do not have toilets and/or septic tanks.[14][25]

On January 29, 2008, the Mamamayan Para sa Pagpapanatili ng Pagpapaunlad ng Lawa ng Laguna (Mapagpala) accused the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA) of the deterioration of Laguna de Bay due to multiplication of fish pens beyond the allowable limit.[26]

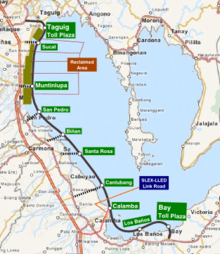

Laguna Lakeshore Expressway Dike

The Laguna Lakeshore Expressway Dike is a proposed expressway that will start from the coastal area of Laguna de Bay from Taguig in Metro Manila to Calamba and Los Baños in Laguna.The project aims to provide a high-standard highway that will speed up traffic between the southern part of Metro Manila and Laguna, as well as a dike that would mitigate flooding in the western coastal communities along Laguna Lake.

Protection and conservation of Laguna de Bay

According to the Clean Water Act of 2004, the DENR (through the LLDA) shall implement a wastewater charge system in all management areas including the Laguna Lake region and Regional Industrial Centers through the collection of wastewater charges/fees. The system shall be established on the basis of payment to the government for discharging wastewater into the water bodies. Wastewater charges shall be established taking into consideration the following: a) to provide strong economic inducement for polluters to modify their production or management processes or to invest in pollution control technology in order to reduce the amount of water pollutants generated; b) to cover the cost of administering water quality management or improvement programs, including the cost of administering the discharge permitting and water pollution charge system; c) reflect damages caused by water pollution on the surrounding environment, including the cost of rehabilitation; d) type of pollutant; e) classification of the receiving water body; and f) other special attributes of the water body.[27]

The technical aspect regarding the quality of wastewater is given in DENR Administrative Order 1990–35. The order defines the critical water parameters’ value versus the classification of the body of water (e.g., lake or river). Discharge permits are issued by the LLDA only if the wastewater being discharged complied with the said order.[28]

Integrated Coastal Ecosystem Conservation and Adaptive Management

CECAM is a 5-year research cooperation between Japanese and Filipino scientists. Seven monitoring instruments are being used as part of the Continuous and Comprehensive Monitoring System (CCMS) provided by the Japanese government.[29]

Cultural impact

Laguna de Bay has had a significant impact on the cultures of the communities that grew up around its shores, ranging from folk medicine to architecture. For example, the traditional cure for a child constantly experiencing nose bleed in Victoria, Laguna is to have the child submerge his or her head in the lake water at daybreak.[30] When nipa huts were more common, huts made in the lake area were constructed out of bamboo that would first be cured in the waters of Laguna de Bay.[31] Some experts on the evolution of local mythologies suggest that the legend of Mariang Makiling may have started out as that of the Lady (Ba'i) of Laguna de Bay, before the legend was transmuted to Mount Makiling.[32]

See also

References

- Sheniak, David; Feleo, Anita (2002), "Rizal and Laguna: Lakeside Sister Provinces (Coastal Towns of Rizal and Metro Manila)", in Alejandro, Reynaldo Gamboa (ed.), Laguna de Bay: The Living Lake, Unilever Philippines, ISBN 971-922-721-4

- Odal-Devora, Grace P. (2002), "'Bae' or 'Bai': The Lady of the Lake", in Alejandro, Reynaldo Gamboa (ed.), Laguna de Bay: The Living Lake, Unilever Philippines, ISBN 971-922-721-4

- "Laguna". Spanish Dict. Retrieved on 2012-10-18.

- U.S. Bureau of Census (1905). "Census of the Philippine Islands, 1903, Vol. II". Government Printing Office, Washington.

- "Official Website of the Laguna Lake Development Authority". www.llda.gov.ph. Archived from the original on 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- Santos-Borja, Adelina C. (2008). "Multi-Stakeholders’ Efforts for the Sustainable Management of Tadlac Lake, The Philippines". Research Center for Sustainability and Environment, Shiga University.

- "Laguna de Bay". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- LLDA 1995, p. 4.

- Gonzales, E. (1987). "A socio economics geography (1961–85) of the Laguna lake resources and its implications to aquatic resources management and development of the Philippine islands" Dissertation. Cambridge University, England, United Kingdom

- Guerrero, R. & Calpe, A. T. (1998). "Water resources management : A global priority". National Academy of Science and Technology, Manila, Philippines

- Nepomuceno, Dolora N. (2005-02-15). "The Laguna de Bay and Its Tributaries Water Quality Problems, Issues and Responses" (PDF). The Second General Meeting Of the Network of Asian River Basin Organizations. Indonesia: Network of Asian River Basin Organizations. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2006. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- LLDA 1995, pp. 4–6.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 1996

- Batu, M. (1996) Factors affecting productivity of selected inland bodies of water in the Philippines: The case of the Laguna Lake 1986 to 1996. Undergraduate thesis. San Beda College, Manila.

- U.S. Army corps of Engineers (1954). "Manila (topographical map)". University of Texas in Austin Library. Retrieved on 2014-08-03.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-04. Retrieved 2016-01-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Westfall, Matthew (6 September 2012). "Devil's Causeway: The True Story of America's First Prisoners of War in the Philippines, and the Heroic Expedition Sen". Rowman & Littlefield – via Google Books.

- Aquino; Tango; Canoy; Fontanilla; Basiao; Ong; and Quilang (2011). "DNA barcoding of fishes of Laguna de Bay, Philippines". Mitochondrial DNA. 22 (4): 143–153. doi:10.3109/19401736.2011.624613.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Santos-Borja, A., and D.N. Nepomuceno (2005). Laguna de Bay, Experiences and lessons learned brief Archived 2009-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, pp. in: 225–258 in: Lake Basin Management Initiative. Retrieved 13 November 2012

- Cuvin-Aralar, M.L.A. (2016). "Impacts of aquaculture on fish biodiversity in the freshwater lake Laguna de Bay, Philippines". Lakes & Reservoirs. 21 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1111/lre.12118.

- "Republic Act no. 4850". Laguna Lake Development Authority. Retrieved on 2012-10-22.

- LLDA 2009, p. 9.

- DENR, 1997

- Sly, 1984

- Solidarity for People’s Power (1992) Laguna de bay: Racing against time. Pamphlet article. Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines.

- "Group blames LLDA for Laguna Lake's deterioration". philstar.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources (2005). "Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Clean Water Act of 2004 (Republic Act no. 9275)." Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine DENR Website. Retrieved on 2012-10-20.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources (1990). Administrative Order No. 35, March 20, 1990 'Revised Effluent Regulations of 1990, Revising and Amending the Effluent Regulations of 1982'. Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine DENR Website. Retrieved on 2012-10-20.

- "Why JICA is deploying sensors in Laguna Lake". abs-cbnnews. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- Remi E. de Leon (2005). "Health Knowledge Processes and Flows in a Coastal Community in Victoria, Laguna Philippines; (Master's Thesis)". University of the Philippines Los Baños Graduate School. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Morales, Izah (2008-09-22). "Being Filipino: Constructing a Modern-Day 'Bahay Kubo'". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2011-10-31. Retrieved 2008-04-26.

- Odal-Devora, Grace P. (2002). ""Bae" or "Bai": The Lady of the Lake". In Alejandro, Reyndaldo Gamboa (ed.). Laguna de Bay: The Living Lake. Unilever Philippines. ISBN 971-922-721-4.

Sources

- Laguna Lake Development Authority, LLDA (2009). "2009 Annual Report".

- Laguna Lake Development Authority, LLDA (1995). "Laguna de Bay Master Plan – Final Report".

Further reading

- Canonoy, F. V. (1997). Lake Laguna's environmental user fee system.

- Laguna Lake Development Authority. "Frequently Asked Questions (archived 2007-06-08)".

- McKitrick, R. (1999). A derivation of the marginal abatement cost curve.

- National Statistical Coordination Board (1996). Estimation of fish biomass in Laguna de Bay based on primary productivity.

External links

- Laguna Lake Development Authority

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laguna de Bay. |