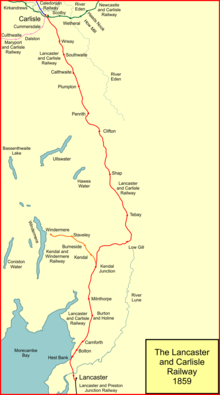

Lancaster and Carlisle Railway

The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway was a main line railway opened between those cities in 1846. With its Scottish counterpart, the Caledonian Railway, the Company launched the first continuous railway connection between the English railway network and the emerging network in central Scotland. The selection of its route was controversial, and strong arguments were put forward in favour of alternatives, in some cases avoiding the steep gradients, or connecting more population centres. Generating financial support for such a long railway was a challenge, and induced the engineer Joseph Locke to make a last-minute change to the route: in the interests of economy and speed of construction, he eliminated a summit tunnel at the expense of steeper gradients.

The sparseness of the population discouraged the addition of branch lines, with a small number of exceptions, although several east-west secondary routes made independent connection to the route. Establishing a joint station at Carlisle with the three other railway companies terminating there, seemed obviously appropriate, but proved hugely difficult, and the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway funded the main station practically single-handedly, in the face of outright obstruction.

The line was electrified in 1974 and at the present day is a key part of the West Coast Main Line, carrying long-distance passenger and freight trains.

Extending northwards

In 1830 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened, heralding a new age of steam powered public railways.[1] It did not take many years for a railway network to form, and by October 1838 it reached Preston, enabling through journeys from London.[2] On 26 June 1840 the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway further extended the network north as far as Lancaster.[3]

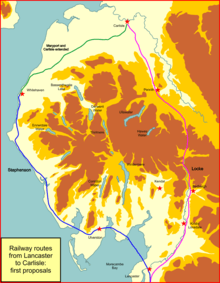

Already in 1835 many observers saw that a trunk line connecting England and Scotland could be expected soon; surveys had already been carried out and routes suggested. George Stephenson had developed two routes, a direct one via Shap following the valley of the River Lune. This involved steep gradients, which Stephenson disliked, and he preferred a route crossing Morecambe Bay by a long barrage, and round the Cumberland coast. This had much easier gradients and would serve numerous populated settlements, but at the expense of considerable extra distance. Stephenson’s proposals were not carried forward at this stage. Joseph Locke carried out a series of assessments of practicable routes in the years 1835 to 1837, not all of them actual surveys. In particular, on 4 November 1836 Joseph Locke was commissioned by the Grand Junction Railway to "report on the practicability of making a railway communication between Preston and Glasgow".[4][5] He proposed a route passing east of Lancaster and running up the valley of the River Lune past Kirkby Lonsdale. There was to be a summit tunnel at Shap, 1 1⁄4 miles long, after which the line would descend through Bampton, Askham and Penrith into Carlisle. The steepest gradients were to be 1 in 100. His report was well received, but no progress was made at this stage.[6]

In 1837 George Stephenson was commissioned by interests in the Whitehaven area to design a route round the coast of Cumberland linking with the Maryport and Carlisle Railway. Stephenson was sceptical about the ability of locomotives of the day to ascend gradients, and he was happy to prepare a route that followed the coast closely, crossing Morecambe Bay from Poulton-le-Sands to Humphrey Head, crossing to Ulverston and then tunnelling under the Furness peninsula and crossing the Duddon Estuary, next following round the Cumberland coast to Whitehaven, where a railway from Carlisle was already proposed. Modifications to that prodigious scheme were put forward the following year.[6][7]

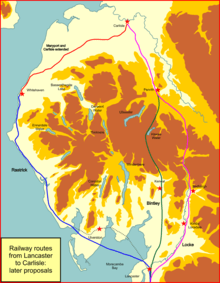

At the time Kendal was a significant community of 9,000 persons, and local interests were dismayed to be by-passed by Locke's scheme. They argued that a line could be made running north from Kendal up Long Sleddale. At the head of the valley a 2 1⁄4 mile tunnel could take the line to a viaduct over Mardale, and the line would then follow the west side of Haweswater[note 1] to Bampton and Penrith. The tunnel under Gatescarth Pass (1,950 feet above sea level) would require construction shafts 700 feet deep.[6] Meanwhile Locke revisited his Lune Valley route and proposed a deviation between Tebay and Penrith, involving a shorter tunnel under Orton Scar, before curving to the west through Crosby Ravensworth, Morland and Clifton.[6][8]

The Commission on Railway Communication

Carlisle was not the ultimate destination in these considerations: the issue was a route between the emerging English network and central Scotland. Although Lancaster was an obvious starting point for a westerly route, there were advocates for an eastern route from York. Here too the terrain northwards was a major difficulty: selection of the route of such a line within Scotland was just as controversial as that in England, and it incorporated just as great a difficulty in finding a practicable route.[9][10]

At the time there was a firm belief that only one such route could be sustained, and the Government took the unusual step of establishing a Commission on Railway Communication to determine what that route should be. The Commission was appointed in November 1839 and had two members, Lt Col Sir Frederic Smith and Peter Barlow, Professor of Mathematics at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. Their task was to examine the whole question of railway communication between England and Scotland, as well as between London and Ireland.[10][11]

The Smith and Barlow Commission became bogged down by energetic advocacy of rival schemes, and their first report of May 1840 was ambiguous. However it rejected the Stephenson scheme for a Cumberland coast railway. They suggested that a route combining the Lancaster to Kendal part of the Long Sleddale route and the northern part of the Lune Valley route might be feasible. George Larmer, working as Locke's local engineering representative while Locke was engaged elsewhere, quickly surveyed the connecting link from near Kendal to Borrowbridge in the Lune Valley, finding a route that offered reasonable gradients.

The commission issued a second report in November 1840, which approved Larmer's route, which became the preferred option for a Lancaster to Carlisle line. The Commission stuck to the policy that only one Anglo-Scottish route was viable, but it refrained from any definite recommendation as between west and east coasts. Their opinion was becoming irrelevant, as the west coast faction was now building to Lancaster, and the east coast railways were shortly to reach Newcastle.[6][10][12]

Final route selection

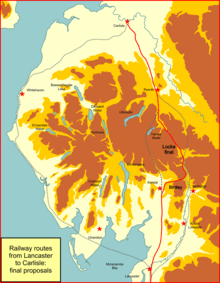

At the time a London to Glasgow journey involved a steamer section, at first from Liverpool to Ardrossan, and from 1840 from Fleetwood to Ardrossan.[13] Provision of a direct railway connection was now inevitable and the Commission's view was no longer authoritative. However the money market had become tight, but after considerable hesitation in committing money, there was a meeting on 6 November 1843 at Kendal which determined to build what became the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway company. The London and Birmingham Railway had offered to subscribe £100,000, the Grand Junction Railway had offered £250,000 and the [North Union Railway]] and the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway had each agreed to take £65,000. Locke was asked to be engineer-in-chief and he made some last minute revisions to the route previously advanced. The line was to strike north from the Penny Lane terminus of the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway and pass round the east side of the town.[note 2] Locke adopted the Lancaster - Oxenholme - Grayrigg - Tebay route, but eliminated the tunnel at Orton Scar, and determined to cross Shap without any tunnel. In doing so he increased ruling gradients from 1 in 140 in the earlier scheme to four miles of 1 in 75. To avoid landowner opposition, he altered the Bampton and Askham route to run via Thrimby Grange and Clifton. The Bill for the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway went forward to the 1844 session of Parliament.[14][15]

Authorisation and construction

The scheme received the Royal Assent without much opposition, on 6 June 1844. Authorised share capital was £900,000.[16][17][18][16]

The line was to be built as a single track with land acquired sufficient for double track. However on 4 October 1844 the directors resolved: "That viewing probable increase of traffic and the extension of the railway to Scotland... it is desirable that this board shall recommend to the shareholders at a special meeting to be held as early as possible, to lay down a double line of rails for the whole line or for any part that may be considered desirable." This was obviously in consideration of a continuation to central Scotland, although it was nine months before the Caledonian Railway Act of Incorporation of 31 July 1845.[19][16]

In early 1845 a petition was received from citizens of Lancaster, asking that the new line should pass to the west of the town, near the navigable section of the River Lune. This was agreed to, and an amending Act obtained on 30 June 1845 authorising a deviation line leaving the L&PJR south of Lancaster, and passing through a new Lancaster station; the old L&PJR station was thus to remain a terminus. Kendal interests were also dismayed to learn that the L&CR would pass about two miles from their town, and they quickly developed a scheme for a branch line to their town, running on to the shore of Windermere. Approval for the Kendal and Windermere Railway was received in the same Act as the Lancaster deviation, without opposition in Parliament; authorised capital was £125,000.[20]

Construction and opening

The allied railways building the east coast route to Scotland, via Berwick,[note 3] were pressing ahead, and there was serious concern that if the L&CR was not built swiftly, it would suffer a huge competitive disadvantage.

The line was opened between Lancaster and Kendal Junction (later named Oxenholme) was opened formally on 21 September 1846, and the following day to the general public. For the time being it was a single line only. The section from Kendal Junction to Kendal on the Windermere line was opened on the same day. On 15 December 1846 the remainder of the line from Kendal Junction to Carlisle was opened formally, and fully on 17 December 1846. By January 1847 double track had been installed throughout.[21] Two passenger trains ran each way daily throughout on the line at first.[22][17][23]

The Caledonian Railway opened its line from Carlisle northwards to Beattock on 11 September 1847, the first stage of its own construction.[23][24]

Windermere branch

The first branch connection of any sort off the L&CR was the Kendal and Windermere Railway. The two miles from Kendal Junction (later named Oxenholme) to Kendal opened to passenger traffic with the southern section of the L&CR on 22 September 1846, but goods traffic was delayed until 4 January 1847. The Kendal to Windermere section was opened on 20 April 1847.[25][20]

Company amalgamations

The L&CR depended on the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway for its southward connection. At the end of 1844, the common interests of the L&CR and the L&PJR Railway were becoming plain, and talk of an amalgamation turned into serious negotiation. An arrangement was agreed, but the L&PJR shareholders refused the proposal. The directors of the L&PJR felt aggrieved that their considerable hard work in negotiation was so casually cast aside, and they all, except one, resigned. This left the L&PJR without a properly constituted directorate, and it was unable to function at corporate level.

The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway had been backed by the money of principal investors in more southerly railways, who saw the advantage of a future west coast main line to Scotland. On 16 July 1846, just as the Lancaster-Carlisle was nearing completion, a merger occurred between three important concerns: the London and Birmingham Railway, the Grand Junction Railway and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway amalgamated to form the London and North Western Railway. The L&CR had agreed that the Grand Junction Railway would work its line, and the LNWR therefore inherited that task. The L&CR wished to form connecting and through services with the LNWR at Preston, so the paralysis in the intervening L&PJR was a problem. Accordingly the L&CR gave notice of its intention to run trains over the L&PJR when it opened from Lancaster to Kendal, and nobody had the authority to prevent it. This service began on 22 September 1846.[17][23]

Opening on 15 February 1848, the Caledonian Railway now connected Glasgow and Edinburgh into the west coast network. This led to a huge increase in business, and a 44 per cent rise in the receipts of the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway. Nevertheless the new Anglo-Scottish expresses were running without authority over the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway. The L&CR was carefully accounting for the toll charges it would pay, against the day when there was an active owning company to which it could pay them. The alarming situation was discussed at a shareholders' general meeting on 4 August 1848, when authority was given to plan an independent line between Lancaster and Preston, as no resolution of the dangerously unsatisfactory status quo seemed imminent. In fact matters were brought to a head by a rear-end collision at Bay Horse, on the L&PJR line, on 21 August 1848, when a London to Glasgow express passenger train ran into a stationary train carrying out station duties there. One person was killed and several injured. The subsequent Board of Trade Inquiry report elaborated the entire chaotic situation, and public opinion forced the L&PJR to re-constitute itself.[26][27][28]

On 1 August 1849 the management of the L&PJR line was taken over by the L&CR. Up until this time the L&PJR had been running local trains from its terminus at Lancaster, but now all passenger business was transferred to the L&CR station, and the L&PJR terminus became a goods station.

The full amalgamation of the L&PJR with the L&CR, and the lease of the Kendal and Windermere Railway were authorised by Act of 13 August 1859. Within the next month the L&CR, including the properties which had belonged to these two other lines, was leased for 900 years to the LNWR as from 1 August 1859. Thus the L&CR came to an end as an active operator.[29]

Connecting railways

The North Western Railway[note 4] wanted to connect Morecambe, where a harbour was being developed, with Skipton. The NWR opened a line from Morecambe to its own station at Lancaster, Green Ayre in 1848 and was extended eastward to Wennington, joining the uncompleted Skipton to Low Gill route there, on 17 November 1849. The NWR opened a single track connection from Green Ayre to the L&CR Lancaster Castle station on 19 December 1849.

The Ulverston and Lancaster Railway was incorporated on 24 July 1851, to make a line from Ulverston to Carnforth. It opened to goods traffic on 10 August 1857 and to passenger traffic on 16 August 1857. The Furness Railway and the Midland Railway jointly built a line from Carnforth to Wennington, on the North Western Railway line, and this opened in 1867.

In 1849 the North Western Railway had opened its line from Skipton to Ingleton. In 1855 there was an upsurge in interest in rival long-distance railways and the idea of continuing to Low Gill, originally authorised but never completed, was revived. The L&CR saw that this was a threat to abstract traffic from it, and it promoted its own Bill for a line from near Tebay to Ingleton. This was obviously a spoiling tactic, and Parliament inserted a clause into the Bill requiring the L&CR Ingleton branch to be physically connected to the NWR terminus there. The Act was passed on 25 August 1857 with additional capital of £300,000. The junction at Low Gill was to be triangular. Having achieved the object of blocking the approach of other railways, the L&CR was no hurry to build the line, and it opened after the LNWR takeover, on 24 August (goods) and 16 September (passengers), 1861. The south curve of the intended triangular Low Gill junctions was never built.

The LNWR did what it could to discourage through traffic. Through running at Ingleton did not take place, and at Tebay there were no worthwhile connections. Midland Railway carriages to or from Scotland were not permitted for a long time. The Midland Railway later took over the North Western Railway, but eventually gave up the idea of running from Leeds to Carlisle over the line and the L&CR (now LNWR) north from Low Gill. In frustration the Midland Railway promoted what became the Settle and Carlisle Line. The LNWR saw that this would abstract far more business than if it permitted the Midland Railway to use its line from Low Gill to Carlisle, on which it could charge tolls on the traffic, and it belatedly offered to concede the facility. The Midland Railway wished to take advantage of this, which would avoid the expense of constructing the Settle and Carlisle Line, but Parliament refused to allow the abandonment of the project. In this way the LNWR secured a pyrrhic victory, and the Midland Railway was obliged to construct the Settle and Carlisle line.[30]

One more branch was promoted by the L&CR before the LNWR takeover. A short loop was authorised from Hest Bank to a junction on the Little North Western line at Bare Lane, on the outskirts of Morecambe. The Royal Assent was obtained on 13 August 1859, and it was the LNWR that actually built the line. It opened on 8 August 1864. It was built as double track, but was soon singled.[31]

Carlisle

At the time of the incorporation of the L&CR there were two railways already in Carlisle: the Maryport and Carlisle Railway and the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway. In March 1844 the L&CR board discussed a possible joint station with the Maryport and Carlisle Railway. The M&CR had a Bill in Parliament for an extension to an improved station of its own, at Crown Street, and felt that its Bill should proceed, but undertook to make arrangements with the L&CR for the joint use of this station and land to the south-west of it. At this stage the eventual construction of the Caledonian Railway was regarded as certain, although that company's powers were not being applied for yet. Next month the L&CR suggested that if the M&CR station Bill was withdrawn, the L&CR, the N&CR, and the Caledonian would share the M&CR's Parliamentary expenses among them, and that the four companies should then form a joint station committee to decide on the best site and other matters. The N&CR gave this idea approval in principle, but the M&CR declined.

The L&CR made agreements with the N&CR in the summer of 1845 to use their London Road station from when the L&CR reached Carlisle, until such time as a joint station was completed. London Road station was reached by a short extension spur from Upperby, but the station was itself on a spur facing Newcastle, so L&CR trains had to reverse into it.

The question of the joint station was on hold awaiting the formation of the Caledonian Railway. In May 1845, the L&CR tried to get the issue moving again, but the M&CR continued to obstruct an agreement, and retaining a plot of intervening land needed by the L&CR approach to the intended joint station. The N&CR too prevaricated, hoping to get compensated for its expenditure on the London Road station. Considerable negotiation on points of detail continued, until from the beginning of 1846 the L&CR determined to have one common station at Carlisle, even if it had to provide all the money itself. A Bill for the station was passed on 27 July 1846. The new station began to be referred to as "Citadel" from February 1847. The Caledonian Railway got its Act the same day for a line to approach the station from the north.[32]

In 1846 the M&CR planned to cross the N&CR’s Canal Branch to get direct access to its Crown Street station, which had hitherto been reached by a reversal on the N&CR line. In the summer of 1847 the L&CR construction was approaching Citadel, and crossed the existing Crown Street branch on the level, and it crossed the N&CR Canal branch on the level at St Nicholas. In 1849 the L&CR went to law to get possession of M&CR ground it needed. From 1 June 1851, M&CR trains used Citadel station, at first by reversal off the N&CR line, but from 8 August 1852 up the new direct spur from Bog Street.

On 24 May 1847 the L&CR wrote to the three other companies; it had by now expended £60,000 on the joint station, and it invited the other companies to contribute some money at once, in the proportions 3:3:3:1 (L&CR:NCR:Caledonian:M&CR). Only the N&CR responded, sending a cheque for part of the sum requested. In frustration the L&CR returned the cheque and stated that it could no longer treat the N&CR as a party to the construction of the joint station; this action resulted in a complete breakdown of relations.

The L&CR diverted its trains to the Citadel station in September 1847, probably 1 September: the station was far from complete. The Caledonian Railway started using the station on 10 September 1847 when the first part of its own line was opened, as far as Beattock.[32]

The L&CR negotiated briefly in March 1848 to lease the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway. George Hudson, the so-called Railway King, was chairman of the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway, and he saw the N&CR as part of his kingdom. He was accustomed to using underhand tactics, and was later found out and disgraced At this stage however, he immediately leased the N&CR, from 1 August 1848, to keep the L&CR away. He soon went further, leasing the M&CR from 1 October in the same year. The alignment of the L&CR approaching from the south crossed the N&CR Canal Branch on the level at St Nicholas, and also the M&CR Crown Street line on the level. An M&CR passenger train arriving at Crown Street crossed the L&CR line on the level three times in doing so; if the train proceeded to London Road, as some did, and its engine returned light, then five level crossings of the L&CR took place.

The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway considered the M&CR Crown Street terminal to be temporary, and actually illegal. It negotiated with the M&CR and offered £7,005 for the land it needed for the development of Citadel station. Hudson intevened, and demanded £100,000. A jury was appointed to assess the value of the land, and it decided on £7,171, which the L&CR immediately paid. Hudson still refused to give up the land, and the L&CR called in the Under Sheriff of Cumberland. At 10 am on 17 March 1849 that officer took possession of the site and handed it over to the solicitor of the L&CR. Workmen employed by the L&CR immediately dismantled Crown Street station and the tracks there. Hudson's fall from power took place shortly afterwards, and Parliament refused to sanction his leases of the N&CR and the M&CR, so that control of those networks reverted to the owning companies.

The M&CR now reached an agreement with the L&CR and the Caledonian Railway, and became a permanent tenant of Citadel station, effective from 1 June 1851. Its trains reversed into the station from the London Road direction on the N&CR, until a direct curve was opened on 8 August 1852.[32]

The N&CR never used Citadel station, and it was not until the North Eastern Railway took over the N&CR on 17 July 1862 that discussion resumed, and the NER used Citadel from 1 January 1863 as a tenant. The N&CR had always run on the right-hand track and the start of regular train working into Citadel showed this to be a problem. In 1864 the NER changed the running to normal left hand running, and to suit this some signal alterations had to be made around St Nicholas crossing and junction.

It was left to the L&CR and the Caledonian Railway between them to share the cost of Citadel, but the Caledonian was not a good payer. By July 1847 the L&CR had advanced £56,490 on the station, and the Caledonian had only paid in £5,000. It was not until 1854, when the station works had cost £178,324, that the Caledonian Railway then paid £85,391 as its portion. This great leniency of the L&CR over a long and difficult period was probably motivated by the desire that the Caledonian Railway should emerge as a vigorous partner in the Anglo-Scottish trade.

The level crossing of the N&CR Canal Branch was hardly appropriate for a main line railway, and on 7 July 1877 a new L&CR alignment came into use carrying the main line over the Canal Branch, which was itself realigned.[33]

Absorption by the LNWR

Finding itself now very prosperous, thanks to the Anglo-Scottish traffic, the L&CR delayed absorption by the LNWR, until on 10 September 1859 it leased its line to the LNWR. The terms were very generous to L&CR shareholders, as the LNWR feared the line's allegiance might pass to the Midland Railway, which at that time was advancing towards Carlisle from Leeds. The L&PJR amalgamated with the L&CR immediately before this arrangement, so that the whole line from Preston to Carlisle was included. The L&CR was vested outright in the LNWR from 21 July 1879.[26]

Reed observes that:

During the 15 years’ independent working existence of the L&CR the board had had to suffer only one open contretemps, though there were internal dissensions from time to time. Dividends continued to rise until the beginning of 1855, when, due to the depression in general trade, the Crimean War, and a slight decrease in the Anglo-Scottish traffic, there was a fall in receipts and a small drop in the dividend rate. Seizing on this as an excuse, disturbed at what was said to be frequent LNWR domination, and angry that the board would not sanction a lease of the Little North Western Railway, a section of the shareholders led by John Barker, of Milnthorpe, made sweeping charges of defective management causing weak dividends. At the half-yearly meeting in September 1855 at which the issue came to a head, the board adjourned the meeting and asked for a committee of enquiry. This was, perhaps, the only case of such charges being made against a board that had been paying 8 to 8 1⁄4 per cent and had dropped only to 7 1⁄4 per cent, all paid out of revenue.[34]

LNWR branches

Two branch lines off the L&CR main line were promoted and built by the LNWR after the takeover. A double-track south curve from the Lancaster direction leading to the Hest Bank branch near Bare Lane was authorised by Act of 19 July 1887, and opened on 19 May 1888.

Later development of the line

The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway line was a key part of the west coast route from London to Glasgow. The line continued as the principal route through Carlisle, and to this day is part of the West Coast Main Line. The steep gradients designed by Locke was for many years an operational difficulty, and all but the lightest trains had to be assisted by a banking engine or a pilot engine. Even after the introduction of diesel traction, this necessity continued, only being obviated on electrification of the route.

Electrification

The Preston to Carlisle section of the West Coast Main line was electrified on the 25kV overhead system; it was energised on 25 March 1974. A full electrically operated train service started on 6 May 1974. On 7 May HM the Queen travelled the route and 'drove' the train from Preston to Lancaster.[35]

Locations

Lancaster and Carlisle Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Lancaster Old Junction; divergence from L&PJR line to 1967;

- Lancaster; opened 22 September 1846; Bradshaw showed this as Lancaster New Bailey in first months, and occasionally as Lancaster Castle later; still open;

- Morecambe South Junction; divergence to Morecambe from 1888;

- Hest Bank; opened 22 September 1846; closed 3 February 1969;

- Bolton; opened 7 August 1847; Bolton-le-Sands shown in Bradshaw from 1861; closed 3 February 1969;

- Carnforth; opened 22 September 1846; both Carnforth and Carnforth-Yealand used in timetables 1849 to 1864; Yealand was probably added due to a clerical error; main line platforms closed 4 May 1970; branch platforms still open;

- Burton and Holme; opened 22 September 1846; closed 27 March 1950;

- Milnthorpe; opened 22 September 1846; closed 1 July 1968;

- Hincaster Junction; convergence of Furness Railway line from Arnside, 1876 - 1963;

- Kendal Junction; opened 22 September 1846; Oxenholme was used in Bradshaw and other documentation; definitely Oxenholme from 1898; renamed Oxenholme Lake District 11 May 1987; still open;

- Grayrigg; opened by 8 July 1848; closed 1 November 1849;

- Low Gill; opened 17 December 1846; closed 1 November 1861;

- Low Gill Junction; opened 16 September 1861; renamed Low Gill from 1883; closed 7 March 1960;

- Tebay; opened 17 December 1846; closed 1 July 1968;

- Shap Summit; workmen's platform for Shap Granite Company, probably from mid-1880s to autumn 1956;

- Shap; opened 17 December 1846; closed 1 July 1968;

- Clifton; opened 17 December 1846; renamed Clifton and Lowther 1 February 1877; closed 4 July 1938

- Eden Valley Junction; convergence of Eden Valley Line 1863 - 1962;

- Eamont Junction; divergence of Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway, 1864 - 1972;

- Penrith; opened 17 December 1846; shown as Penrith for Ullswater Lake (sic) in timetables from 1904; simply Penrith from 6 May 1974; renamed Penrith North Lakes 18 May 2003; still open;

- Plumpton; opened 17 December 1846; closed 31 May 1948;

- Calthwaite; opened by 28 July 1847; closed 7 April 1952;

- Southwaite; opened 17 December 1846; closed 7 April 1952;

- Wreay; opened December 1852, replacing Brisco; closed 16 August 1943;

- Brisco; opened 17 December 1846; closed November 1852;

- Upperby Bridge Junction; connection to goods lines from 1877;

- Upperby Junction; connection towards N&CR line;

- Carlisle; opened by 10 September 1847; various combinations with "Citadel" and "Joint" used in timetables; still open.

Notes

- The body of water was much altered after 1929 when it was made into Haweswater Reservoir.

- Lancaster became a city in 1937.

- Later named Berwick-upon-Tweed.

- The North Western Railway is usually referred to informally as the Little North Western Railway to distinguish it from the better known London and North Western Railway.

References

- Geoffrey Holt and Gordon Biddle, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 10: the North West, David St John Thomas, Nairn, 1986, ISBN 0 946537 34 8, page 20

- Holt and Biddle, page 200

- Holt and Biddle, page 224

- Brian Reed, Crewe to Carlisle, Ian Allan, London, 1973, ISBN 0 7110 0057 3, page 95

- David Joy, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume VIII: South and West Yorkshire, David & Charles Publishers, Newton Abbot, 1984, ISBN 0-946537-11-9, page 16

- Joy, page 19 to 22

- Reed, page 99

- Reed, pages 105 and 106

- C J A Robertson, The Origins of the Scottish Railway System, 1722 - 1844, John Donald Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh, 1983, ISBN 0-85976-088-X, pages 268 to 274

- Reed, pages 111 to 113

- Robertson, pages 274 to 278

- Reed, pages 116 to 120

- Holt and Biddle, pages 215 and 216

- Joy, pages 23 and 24

- Reed, pages 117 to 120

- Joy, pages 24 to 28

- Holt and Biddle, page 226

- Reed, page 120

- Reed, page 140

- Joy, page 201

- Reed, page 155

- Reed, page 158

- Joy, pages 26 to 28

- Reed, page 159

- Reed, page 198

- Holt and Biddle, pages 227 and 228

- Captain R M Laffan, Lancaster & Preston Railway: Report to Commissioners of Railways, Board of Trade, 24 August 1848

- Reed, pages 86 and 91

- Reed, page 131

- Reed, pages 194 and 196

- Reed, page 196

- Joy, pages 67, 68, 73, 76 and 77

- Joy, page 85

- Reed, page 121

- J C Gillham, The Age of the Electric Train, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 1988, ISBN 0 71101392 6, pages 169 and 170

- Michael Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England, Scotland and Wales: A Chronology, the Railway and Canal Historical Society, Richmond, Surrey, fifth (electronic) edition, 2019

- Col M H Cobb, The Railways of Great Britain: A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 2002

Further reading

- George Samuel Measom (1859), Official Illustrated Guide to the Lancaster and Carlisle, Edinburgh & Glasgow, and Caledonian Railways, London: W.H. Smith and Son

External links

- Notes on L&CR includes map and photographs

- Illustrated London News report on opening of L&CR including a detailed description of the railway