Chinese archery

For millennia, Chinese archery (simplified Chinese: 中华射艺; traditional Chinese: 中華射藝; pinyin: zhōnghuá shè yì, the art of Chinese archery) has played a pivotal role in Chinese society.[1] In particular, archery featured prominently in ancient Chinese culture and philosophy: archery was one of the Six Noble Arts of the Zhou dynasty (1146–256 BCE); archery skill was a virtue for Chinese emperors; Confucius[2] himself was an archery teacher; and Lie Zi (a Daoist philosopher) was an avid archer.[3][4] Because the cultures associated with Chinese society spanned a wide geography and time range, the techniques and equipment associated with Chinese archery are diverse.[5] The improvement of firearms and other circumstances of 20th century China led to the demise of archery as a military and ritual practice, and for much of the 20th century only one traditional bow and arrow workshop remained.[6] However, in the beginning of the 21st century, there has been revival in interest among craftsmen looking to construct bows and arrows, as well as practice technique in the traditional Chinese style.[7][8]

The practice of Chinese archery can be referred to as The Way of Archery (Chinese: 射道; pinyin: shè dào), a term derived from the 17th century Ming Dynasty archery manuals written by Gao Ying (simplified Chinese: 高颖; traditional Chinese: 高穎; pinyin: gāo yǐng, born 1570, died ?).[9] The use of 道 (pinyin: dào, the way) can also be seen in names commonly used for other East Asian styles, such as Japanese archery (kyūdō) and Korean archery (Gungdo).

Use and practice

In historical times, Chinese people used archery for hunting, sport, rituals, examinations, and warfare.[10]

Warfare

China has a long history of mounted archery (shooting on horseback). Prior to the Warring States period (475–221 BCE ), shooting from chariot was the primary form of battlefield archery. A typical arrangement was that each chariot would carry one driver, one halberder, and one archer. Eventually, horseback archery replaced chariot archery during the Warring States period. The earliest recorded use of mounted archery by Han Chinese occurred with the reforms of King Wuling of Zhao in 307 BCE. Despite opposition from his nobles, Zhao Wuling's military reforms included the adoption of archery tactics of the bordering Xiongnu tribes, which meant shooting from horseback and eschewing Han robes in favor of nomadic-style jodhpurs.[11]

For infantry, the preferred projectile weapon was the crossbow, because shooting one required less training than shooting a bow. As early as 600 BC[12], Chinese crossbows employed sophisticated bronze trigger mechanisms, which allowed for very high draw weights.[13] However, crossbow trigger mechanisms reverted to simpler designs during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), presumably because the skill of constructing bronze trigger mechanisms was lost during the Mongolian Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 CE).[12] Nonetheless, infantry archery using the bow and arrow still served important functions in training as well as naval battles.[14]

Ritual and examination

In the Zhou dynasty (1146–256 BCE), nobles regularly held archery rituals[15] which symbolized and reinforced order within the aristocratic hierarchy. The typical arrangement involved pairs of archers shooting at a target in a pavilion, accompanied by ceremonial music and wine. In these rituals, shooting with proper form and conduct was seen important in order to hit the target.[14][16] Ritual archery served as a counterpoint to the typical portrayal of archers, who were often skillful but brash. Confucius himself was an archery teacher, and his own view on archery and archery rituals was that "A refined person has no use for competitiveness. Yet if he cannot avoid it, then let him compete through archery!"[17]

Although civil archery rituals fell out of favor after the Zhou dynasty, examinations inspired by the Zhou-era rituals became a regular part of the military syllabus in later dynasties such as the Han,[18] Tang,[19] Song,[20] Ming[21] and Qing.[22] These exams provided merit-based means of selecting military officials. (Imperial examination#Military examinations) In addition to archery on foot, the examinations also featured mounted archery, as well as strength testing with specially-designed strength testing bows.[23]

Football and archery were practiced by the Ming Emperors.[24][25] Equestrianism and archery were favorite pastimes of He Suonan who served in the Yuan and Ming militaries under Hongwu.[26] Archery towers were built by Zhengtong Emperor at the Forbidden City.[27] Archery towers were built on the city walls of Xi'an erected by Hongwu.[28] Lake Houhu was guarded by archers in Nanjing during the Ming dynasty.[29]

Math, calligraphy, literature, equestrianism, archery, music, and rites were the Six Arts.[30]

At the Guozijian, law, math, calligraphy, equestrianism, and archery were emphasized by the Ming Hongwu Emperor in addition to Confucian classics and also required in the Imperial Examinations.[31][32][33][34][35][36] Archery[37] and equestrianism were added to the exam by Hongwu in 1370 like how archery and equestrianism were required for non-military officials at the 武舉 College of War in 1162 by the Song Emperor Xiaozong.[38] The area around the Meridian Gate of Nanjing was used for archery by guards and generals under Hongwu.[39]

The Imperial exam included archery. Archery on horseback was practiced by Chinese living near the frontier. Wang Ju's writings on archery were followed during the Ming and Yuan and the Ming developed new methods of archery.[40] Jinling Tuyong showed archery in Nanjing during the Ming.[41] Contests in archery were held in the capital for Garrison of Guard soldiers who were handpicked.[42]

Equestrianism and archery were favored activities of Zhu Di (the Yongle Emperor) and his second son Zhu Gaoxu.[43]

The Yongle Emperor's eldest son and successor the Hongxi Emperor was disinterested in military matters but was accomplished in foot archery.[44]

Archery and equestrianism were frequent pastimes by the Zhengde Emperor.[45] He practiced archery and horseriding with eunuchs.[46] Tibetan Buddhist monks, Muslim women and musicians were obtained and provided to Zhengde by his guard Ch'ien Ning, who acquainted him with the ambidextrous archer and military officer Chiang Pin.[47] An accomplished military commander and archer was demoted to commoner status on a wrongful charge of treason was the Prince of Lu's grandson in 1514.[48]

Archery competitions, equestrianism and calligraphy were some of the pastimes of Wanli Emperor.[49]

Archery and equestrianism were practiced by Li Zicheng.[50]

Hunting

Hunting was an important discipline in Chinese archery, and scenes of hunting using horseback archery feature prominently in Chinese artwork.[51][52]

Aside from using normal bows and arrows, two distinct subgenres of hunting archery emerged: fowling with a pellet bow, and waterfowling with a tethered arrow. Shooting with a pellet bow involved using a light bow with a pouch on the bowstring designed to shoot a stone pellet. The discipline of shooting the pellet bow was allegedly the precursor to shooting with the bow and arrow, and the practice of pellet shooting persisted for many centuries. By contrast, hunting with a tethered arrow (which was meant to ensnare rather than pierce the target) was featured in early paintings, but seemed to have died out before the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE).[53]

Decline

In contrast to Korean and Japanese archery (whose traditions have been preserved through direct transmission), the circumstances of 19th and 20th century China made it difficult for Chinese archery traditions to be directly transmitted to the present day.

Military use of firearms began in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), and general use of gunpowder weapons as early as the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). Despite this adoption, bows and crossbows had remained an integral part of the military arsenal because of the slow firing rate and lack of reliability in early firearms. This situation changed near the end of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE), when the availability of reliable firearms made archery less effective as a military weapon. As such, the Guangxu Emperor abolished archery from the military exam syllabus in 1901.[14]

Between the collapse of Imperial China in 1911 and beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), there was a short-lived effort to revive traditional archery practice. After World War II, traditional bow makers were able to continue their craft until the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when circumstances forced workshops such as Ju Yuan Hao to suspend the manufacture of traditional Chinese bows.[54]

Modern reconstruction and revival

In 1998, Ju Yuan Hao resumed bow making and until recently was the only active workshop constructing bows and arrows in the traditional Chinese style.[6][55]

However, with the dedicated efforts of craftsmen, researchers, promoters and enthusiasts, the practice of traditional Chinese archery has been experiencing a revival in the 21st century. Starting in 2009, they have established an annual Chinese Traditional Archery Seminar.[7][8] Through new understanding and reconstruction of these archery practices, their goal is to create a new living tradition for Chinese archery.[56] Hanfu enthusiasts have also revived the traditional archery ritual.

Technique

Many variations in archery technique evolved throughout Chinese history, so it is difficult to completely specify a canonical Chinese style. The Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) had at least 7 archery manuals in circulation (including a manual by General Li Guang), and the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE) had at least 14 different schools of archery and crossbow theory, and the Qing dynasty saw the publication of books from over 14 different schools of archery.,[57] The commonality among all these styles is that they placed great emphasis on mental focus and concentration.[58]

The style of draw that is most commonly associated with Chinese archery is the thumb draw, which was also the predominant draw method for other Asian peoples such as the Mongolians, Tibetans, Japanese, Koreans, Indians, Turks and Persians.[10][59] However, during earlier periods of Chinese history (e.g., Zhou dynasty), the 3-finger draw was common at the same time that the thumb draw was popular.[60][61]

Furthermore, the various styles of Chinese archery offered different advice on other aspects of shooting technique. For example: how to position the feet, what height to anchor the arrow, how to position the bow hand finger, whether to apply tension to the bow hand, whether to let the bow spin in the bow hand after release, as well as whether to extend the draw arm after release. [62] [63] [64] [65] [66] In addition, the various Chinese styles used a variety of draw lengths: literature, art and photographs depict Chinese archers placing their draw hand near their front shoulder, near their cheek, near their ear, or past their face.[67][68]

The dichotomy between ritual/examination archery technique and battlefield archery technique provides a significant example of the contrasts between different Chinese styles. Wang Ju, an author from the Tang dynasty, favored a ritual/examination style which involved a post-release follow through where the bow spins in the bow hand, and the draw arm extends straight back; by contrast, certain authors such as Zeng Gongliang (Song dynasty), Li Chengfen (who was influenced by Ming dynasty generals Yu Dayou and Qi Jiguang) and Gao Ying (Ming dynasty) eschewed aesthetic elements (such as Wang Ju's follow through) in favor of developing a more practical technique.[14] [69]

Bows

Historical sources and archaeological evidence suggest that a variety of historical bow types existed in the area of present-day China.[5] Most varieties of Chinese bows were horn bows (horn-wood-sinew composites), but longbows and wood composites were also in use. Modern reproductions of Chinese-style bows have adopted shapes inspired by historical designs. But in addition to using traditional construction methods (such as horn-wood-sinew composites), modern craftsmen and manufacturers have used modern materials such as fiberglass, carbon fiber and fiber-reinforced plastic.

The following sections highlight the current understanding on some of the major design categories for Chinese bows.

Scythian-style horn bows

Horn bows of this style tended to be asymmetric and adopted a distinct, curvy deflex-reflex profile (colloquially known as the "cupid bow" shape). Archaeologists have excavated examples of Scythian-style bows dating to the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770–256 BCE) from the Subeixi and Yanghai sites.[70][71]

Longbows (self bows)

Longbows and wood composite bows were popular in southern China, where the humid climate made horn bows more difficult to use. An excavated example of a Chinese longbow was dated to approximately the Warring States – Western Han Dynasty period (475 BCE–9 CE), and its dimensions were 1.59 m long, 3.4 cm wide and 1.4 cm thick.[72][73][74]

Wood laminated bows

Wood laminated bows were popular in southern China because of the humid climate. Based on excavated bows from the Spring and Autumn period through the Han dynasty (770 BCE–220 CE), the typical construction of a Chinese wood laminate was a reflex bow made from multiple layers of wood (such as bamboo or mulberry), wrapped in silk and lacquered.[75] The typical length of such bows was 1.2–1.5 meters.

Long-siyah horn bows

Bows with long siyahs were popular in China from the Han dynasty through the Yuan dynasty (206 BCE–1368 CE). (Siyahs are the non-bending end sections of Asiatic composite bows.) The design shares similarities with Hunnic horn bows.

The Niya, Gansu and Khotan bows are examples of long-siyah bows dating from the late Han to Jin time period (about 200–300 CE).[76][77] During this period, the siyahs tended to be long and thin, while the working sections of the limb were short and broad. However, during the Yuan period, long-siyah bows tended to have heavier siyahs and narrower working limbs than their Han/Jin-era predecessors.[78]

Ming dynasty horn bows

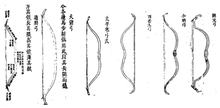

Shorter bow designs became popular during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE).[79] Wubei Zhi (Chapter 102) describes several bow styles popular during the Ming dynasty: in the North, the short-siyah bow, grooved-siyah bow, grooved-bridge bow, and long-siyah bow; in the South, the Chenzhou bow, short-siyah bow, as well as bamboo composite bows finished with lacquer; the Kaiyuan bow was used in all parts of Ming China.[80] The small-siyah bow (小稍弓) differed from earlier Chinese designs in that its siyahs were short and set at an angle forward of the string when at rest. Its design is possibly related to the Korean horn bow.[81] The Kaiyuan bow (开元弓) was a small-to-medium size bow which featured long siyahs, and it was the bow of choice for high-ranking officers.[80]

Wu Bei Yao Lue (Chapter 4), another classic Ming dynasty military manual, depicts a set of bows that is distinct from those discussed in Wubei Zhi. These include the general-purpose bow, the big-siyah bow (which was used for infantry as well as by cavalry), and the Taiping village bow (which resembled a Korean 高丽 bow design and was favored in northern and southern China for its superior craftsmanship).[82]

Although Ming bows have been depicted in literature and art, archaeologists have yet to recover an original Ming bow sample.[83]

Qing dynasty horn bows

The Manchurian Bow[85] design became popular in China during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE). In contrast to other Asiatic composite designs, Qing horn bows were large (up to 1.7 m long when strung) and featured long, heavy siyahs (up to 35 cm in length) with prominent string bridges. The general principle behind this design was to trade arrow speed in favor of stability and the ability to efficiently launch long and heavy arrows, which sometimes exceeded one meter in length.[86]

The Manchurian bow has influenced modern-day Tibetan and Mongolian bow designs, which are shorter versions of the Qing horn bow.[87]

Draw Hand Protection

Because Chinese archers typically used the thumb draw, they often required thumb protection in the form of a ring or leather guard. In historical times, thumb ring materials included jade, metal, ivory, horn and bone (though specimens made of organic materials have been difficult to recover). Because of the importance of archery, the significance of thumb rings extended beyond the battlefield: rings were commonly worn as status symbols, and up until the end of the Han dynasty (220 CE), they were also sacrificial burial objects. Although the archaeological record for Chinese thumb protection is incomplete, the designs of excavated and antique rings suggest that a variety of designs became popular over time.[88][89][90]

The earliest excavated Chinese thumb ring came from the Shang dynasty tomb of Fu Hao (who died circa 1200 BCE). The ring was a slanted cylinder where the front, which contained a groove for holding the bow string, was higher than the back. An excavation of the Marquis of Jin's tomb in Quwo County, Shanxi revealed a Western Zhou jade thumb ring, which had a lipped design but featured taotie decorations similar to the Shang dynasty Fu Hao ring.[91] From the Warring States period through the Han dynasty (475 BCE–220 CE), excavated rings typically had a lipped design with a distinctive spur on the side (there exist several theories about the spur's function).[89] Rings from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) were round cylinders or D-shaped cylinders.[88][92]

Apart from the above examples, describing thumb ring designs from other time periods is difficult. For example, thumb rings are absent from the archaeological record between the Han and Ming dynasties (220–1368 CE) even though contemporary literature (such as Wang Ju's archery manual from the Tang dynasty) indicates that Chinese archers were still using the thumb draw.[90] Moreover, evidence suggests a variety of ring shapes were popular during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE). Li Chengfen's archery manual advocated using rings with oval openings, and Gao Ying's archery manual described the use of lipped rings and contained illustrations depicting an archer using a lipped ring. To date, however, the only recovered rings that purport to be from the Ming dynasty have cylindrical designs that are different from Qing thumb rings.[93]

To date, there are very few (if any) excavated examples of draw hand protection for Chinese archers using the 3-finger draw. However, Xin Ding San Li Tu (a Song dynasty illustrated guide to the Zhou dynasty archery rituals) depicts a tab made of red reed (called Zhu Ji San, 朱极三) for protecting the index, middle and ring fingers while pulling the string.[61]

Legends

Legends about archery permeate Chinese culture. An early tale discusses how the Yellow Emperor, the legendary ancestor of the Chinese people, invented the bow and arrow:

ONCE upon a time, Huangdi went out hunting armed with a stone knife. Suddenly, a tiger sprang out of the undergrowth. Huangdi shinned up a mulberry tree to escape. Being a patient creature, the tiger sat down at the bottom of the tree to see what would happen next. Huangdi saw that the mulberry wood was supple, so he cut off a branch with his stone knife to make a bow. Then he saw a vine growing on the tree, and he cut a length from it to make a string. Next he saw some bamboo nearby that was straight, so he cut a piece to make an arrow. With his bow an arrow, he shot the tiger in the eye. The tiger ran off and Huangdi made his escape.[94]

Another myth was Hou Yi shooting the sun.[95] Other myths also feature Hou Yi battling an assortment of monsters (which were metaphors for natural disasters) using his cinnabar-red bow.[96]

"There once was a man named Cheyn who lived in a village at the foot of a mountain. One day he was attacked by a rabid rabbit. To save himself he took the branch of a tree and the sinew of a nearby dead deer and he picked up a stick off the ground and using his new contraption fired the stick and killed the rabbit. When he returned he was hailed as a hero by the village and made king."

See also

References

Citations

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2010-12-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.manchuarchery.org/photographs

- Six Arts of Ancient China

- Selby (2000), pp. 52, 71, 145—148, 193, 240.

- Selby (2010), pp. 52—54.

- A Brief Chronology of Juyuanhao

- Article about the 2009 Chinese Traditional Archery Seminar

- News coverage of the 2010 Chinese Traditional Archery Seminar

- Tian and Ma (2015), p. 14.

- Selby (2003), p. 65.

- Selby (2000), pp. 174—175.

- "Stephen Selby (2001). A Crossbow Mechanism with Some Unique Features from Shandong, China". Archived from the original on 2018-01-29. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- Selby (2000), pp. 162, 172—173.

- "Selby (2002—2003). Chinese Archery – An Unbroken Tradition?". Archived from the original on 2015-10-12. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- http://www.univ-paris-diderot.fr/eacs-easl/DocumentsFCK/file/BOA14juin.pdf Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine p. 1.

- Selby (2000), pp. 76–77.

- Selby (2000), pp. 75—76.

- Selby (2000), pp. 182—183.

- Selby (2000), pp. 193—196.

- Selby (2000), pp. 248—251.

- Selby (2000), pp. 267—270.

- Selby (2000), pp. 348—356.

- Selby (2000), pp. 352.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2016-05-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/24/ming-british-museum-empire-strikes-back-50-years-changed-china

- Gray Tuttle; Kurtis R. Schaeffer (12 March 2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-0-231-51354-8.

- http://hua.umf.maine.edu/China/HistoricBeijing/Forbidden_City/

- http://hua.umf.maine.edu/China/Xian/pages/023_Xian_wall.html%5B%5D

- https://aacs.ccny.cuny.edu/2009conference/Wenxian_Zhang.pdf p. 165.

- Zhidong Hao (1 February 2012). Intellectuals at a Crossroads: The Changing Politics of China's Knowledge Workers. SUNY Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-0-7914-8757-0.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Stephen Selby (1 January 2000). Chinese Archery. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 267–. ISBN 978-962-209-501-4.

- Edward L. Farmer (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. pp. 59–. ISBN 90-04-10391-0.

- Sarah Schneewind (2006). Community Schools and the State in Ming China. Stanford University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5174-2.

- http://www.san.beck.org/3-7-MingEmpire.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-12. Retrieved 2010-12-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2016-06-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lo Jung-pang (1 January 2012). China as a Sea Power, 1127–1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods. NUS Press. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-9971-69-505-7.

- http://en.dpm.org.cn/EXPLORE/ming-qing/

- Stephen Selby (1 January 2000). Chinese Archery. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 271–. ISBN 978-962-209-501-4.

- Si-yen Fei (2009). Negotiating Urban Space: Urbanization and Late Ming Nanjing. Harvard University Press. pp. x–. ISBN 978-0-674-03561-4.

- Foon Ming Liew (1 January 1998). The Treatises on Military Affairs of the Ming Dynastic History (1368–1644): An Annotated Translation of the Treatises on Military Affairs, Chapter 89 and Chapter 90: Supplemented by the Treatises on Military Affairs of the Draft of the Ming Dynastic History: A Documentation of Ming-Qing Historiography and the Decline and Fall of. Ges.f. Natur-e.V. p. 243. ISBN 978-3-928463-64-5.

- Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1 July 2011). Perpetual happiness: the Ming emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-295-80022-6.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 403–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 404–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 425–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 514–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- "Exploring Chinese History :: Database Catalog :: Biographical Database :: Imperial China- (?- 1644)".

- Selby (2010), p. 60.

- Iconography of Mounted Archery of Western Han Dynasty

- Selby (2000), pp. 178—182.

- Selby (2000), p. 386.

- Translated by Stephen Selby (1999). The History of Ju Yuan Hao Bowmakers of Beijing.

- Asian Traditional Archery Research Network

- Selby (2000), pp. 119—120, 271, 360.

- Stephen Selby (1999).Perfecting the Mind and the Body.

- Koppedrayer (2002), pp. 7—9.

- E.T.C. Werner (1972). Chinese Weapons. Ohara Publications. p. 59. ISBN 0-89750-036-9

- Nie Chongyi (10th century CE). Xin Ding San Li Tu.

- Stephen Selby (1997). The Archery Tradition of China.

- Translated by Stephen Selby (1998).Qi Ji-guang's Archery Method.

- Cheng Ziyi (1638). Illustration from the Wu Bei Yao Lue (‘Outline of Military Preparedness’ : The Theory of Archery).

- Ji Jian (1679). Guan Shi Xin Zhuang.

- Translated by Stephen Selby (1998). 'Makiwara Madness' from the Bukyo Shagaku Sheiso. Gao Ying, 1637.

- Han Dynasty Block Prints (see items [1] and [2] in the thread)

- Selby (2000), pp. xix—xx, xxii—xxiii, 57, 110, 123, 148, 179—181, 205, 340—341, 365—369.

- Selby (2000), pp. 241—242, 276—278, 337.

- Selby (2010), pp. 54—57

- Bede Dwyer (2004). Scythian-Style Bows Discovered in Xinjiang.

- Selby (2003), p. 15.

- ATARN Letters, December 2000

- ATARN Letters, September 2001

- Yang Hong (1992). Weapons in Ancient China. Science Press. pp. 94—95, 196—202. ISBN 1-880132-03-6

- Stephen Selby (2001). Reconstruction of the Niya Bow.

- Stephen Selby (2002). Two Late Han to Jin Bows from Gansu and Khotan.

- Selby (2010), pp. 62—63.

- Selby (2010), pp. 63—65.

- Mao Yuanyi (1621). Wubei Zhi (Chapter 102, Bows).

- Selby (2010), p. 64.

- Cheng Ziyi (1638). Wu Bei Yao Lue (Chapter 4, Illustrations of Infantry and Mounted Archery Methods).

- Selby (2010), p. 63.

- http://war.163.com/photoview/4T8E0001/66781.html#p=9TL9BB9H4T8E0001

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120720220357/http://www.chinese-swords-guide.com/chinese-archery-3.html

- Dekker (2010), pp. 18—19.

- Selby (2003), pp. 38—39.

- Eric J. Hoffman (2008). Chinese Thumb Rings: From Battlefield to Jewelry Box.

- Bede Dwyer (1997—2002). Early Archers' Rings.

- Selby (2003), pp. 54—57.

- "Jades from Major Archaeological Discoveries in China in 2006". Archived from the original on 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- Koppedrayer (2002), pp. 18—30.

- Selby (2000), p. xvii.

- Drawing and translation by Stephen Selby (2003). How Huangdi Invented the Bow and Arrow. Chinese folk tale.

- Hou Yi Shooting the Sun

- Selby (2000), p. 19.

Sources

- Peter Dekker (2010). "Manchu Archery". Journal of Chinese Martial Studies, Summer 2010 Issue 3. Three-In-One Press. pp. 12–25.

- Kay Koppedrayer (2002). Kay's Thumbring Book. Blue Vase Press.

- Stephen Selby (2000). Chinese Archery (Paperback). Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-501-1

- Stephen Selby (2003). Archery Traditions of Asia. Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence. ISBN 962-7039-47-0

- Stephen Selby (2010). "The Bows of China". Journal of Chinese Martial Studies, Winter 2010 Issue 2. Three-In-One Press. pp. 52–67.

- Jie Tian and Justin Ma (2015). The Way of Archery: A 1637 Chinese Military Training Manual. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7643-4791-7

External links

- Asian Traditional Archery Research Network: Chinese Archive

- Fe Doro – Manchu Archery

- Using the cylindrical thumb ring

- http://www.pakua-archery.com

- China Archery: Chinese Folk Archery Federation for All (blog)

- Intro to Chinese archery

- chinese-archery.de – German language Chinese archery site: Containing the use of Chinese bows, arrows, thumb-rings and other equipment in an historical and modern-sporty context