Kurdish phonology

Kurdish phonology is the sound system of the Kurdish dialect continuum. This article includes the phonology of the three Kurdish dialects in their standard form respectively. Phonological features include the distinction between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops and the presence of facultative phonemes.[1][2]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | velar. | plain | labial. | plain | labial. | plain | labial. | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||

| Plosive | voiceless asp. | pʰ | tʰ | t͡ʃʰ | kʰ | |||||||

| vcls. unasp. | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | kʷ | q | qʷ | ʔ | ||||

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ɡʷ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | sˠ | ʃ | x | xʷ | ħ | h | |||

| voiced | v | z | zˠ | ʒ | ɣ | ɣʷ | ʕ | |||||

| Approximant | l | ɫ | j | ɥ | w | |||||||

| Rhotic | ɾ | r | ||||||||||

- /n, t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, t̪, d̪], while /s, z/ are dentalized laminal alveolar [s̪, z̪],[6] pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the back of the upper front teeth, with the tip resting behind lower front teeth.

- Kurdish contrasts plain alveolar /l/ and velarized postalveolar[7] /ɫ/ lateral approximants. Unlike in English, the sounds are separate phonemes rather than allophones.[8]

- Postvocalic /d/ is lenited to an approximant [ð̞]. This is a regional feature occurring in other Iranian languages as well and called by Windfuhr the "Zagros d".[9]

- Kurdish has two rhotic sounds; the alveolar flap (/ɾ/) and the alveolar trill (/r/). While the former is alveolar, the latter has an alveo-palatal articulation.[10]

- According to Hamid (2015), /x, xʷ, ɣ, ɣʷ/ are uvular [χ, χʷ, ʁ, ʁʷ] in Central Kurdish.[11]

- Northern Kurdish distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops, which can be aspirated in all positions. Thus /p/ contrasts with /pʰ/, /t/ with /tʰ/, /k/ with /kʰ/, and the affricate /t͡ʃ/ with /t͡ʃʰ/.[2][8][12]

- Although [ɥ] is considered an allophone of /w/, some phonologists argue that it should be considered a phoneme.[13]

- Kurdish distinguishes between the plain /s/ and /z/ and the velarized /sˠ/ and /zˠ/.[14][15] These velarized counterparts are less emphatic than the Semitic emphatic consonants.[15]

- [ɲ] is an allophone of /n/ in Southern Kurdish, occurring in the about 11 to 19 words that have the consonant group ⟨nz⟩. The word yânza is pronounced as [jɑːɲzˠa].[16]

Labialization

- Kurdish has labialized counterparts to the velar plosives, the voiceless velar fricative and the uvular stop. Thus /k/ contrasts with /kʷ/, /ɡ/ with /ɡʷ/, /x/ with /xʷ/, and /q/ with /qʷ/.[17] These labialized counterparts do not have any distinct letters or digraph. Examples are the word xulam ('servant') which is pronounced as [xʷɪˈlɑːm], and qoç ('horn') is pronounced as [qʷɨnd͡ʒ].[18]

Palatalization

- After /ɫ/, /t/ is palatalized to [tʲ]. An example is the Central Kurdish word gâlta ('joke'), which is pronounced as [gɑːɫˈtʲæ].[8]

- /k/ and /ɡ/ are strongly palatalized before the front vowels /i/ and /e/ as well as [ɥ], becoming acoustically similar to /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/.[2]

- When preceding /n/, /s, z/ are palatalized to /ʒ/. In the same environment, /ʃ/ also becomes /ʒ/.[19]

Pharyngealization

Facultative consonants

- /ħ/ and /ɣ/ are non-native phonemes that are mostly present in words of Arabic origin. Even though they are usually replaced by /h/ and /x/ respectively, they are facultative. Thus the word heft/ḧeft ('seven' /ˈħɛft/) can be pronounced as either [ˈhɛft] or [ˈħɛft], and xerîb/ẍerîb ('stranger', /ɣɛˈriːb/) as either [xɛˈriːb] or [ɣɛˈriːb].[22]

- /ʕ/ is only present in words of Arabic origin and is only present in initial position.[23] An Arabic loanword like "Hasan" would thus be pronounced as /ʕɛˈsɛn/.[24] The phoneme is absent in some Northern and Southern Kurdish dialects.[25]

- /ʔ/ is mainly present in Arabic loan words and affect the pronunciation of that vowel. However, many Kurds avoid using the glottal phoneme for nationalist and purist reasons since the glottal phoneme is seen as the embodiment of Arabic influence in Kurdish.[26]

Vowels

The vowel inventory differs by dialect, some dialect having more vowel phonemes than others. /iː, ʊ, uː, ɛ, eː, oː, ɑː/ are the only vowel phonemes present in all three Kurdish dialects.

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | ||

| Close | iː ɪ |

ʉː ɨ | uː ʊ | ||

| Close-mid | eː | øː | oː o | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ||||

| Open | a | ɑː | |||

Detailed table

| Letter | Phoneme | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern[29] | Central[30] | Southern[31][32] | |

| a | ɑː | a | a[33] |

| â | – | ɑː | ɑː[34] |

| e | ɛ | ɛ | ɛ |

| ê | eː | eː | eː |

| i | ɪ | ɪ | ɨ[35] |

| î | iː | iː | iː |

| o | oː | oː | o |

| ô | – | – | oː |

| ö | – | – | øː[36] |

| u | ʊ | ʊ | ʊ[37] |

| û | uː | uː | uː |

| ü | – | – | ʉː[38] |

Notes

- In Central Kurdish, /a/ is realized as [æ], except before /w/ where it becomes mid-centralized to [ə]. For example, the word gawra ('big') is pronounced as [ɡəwˈɾæ].[39]

- /ɪ/ is realized as [ɨ] in certain environments.[28][40][41]

- In some words, /ɪ/ and /u/ are realized as [ɨ]. This allophone occurs when ⟨i⟩ is present in a closed syllable that ends with /m/ and in some certain words like dims ('molasses'). The word vedixwim ('I am drinking') is thus pronounced as [vɛdɪˈxʷɨm],[40] while dims is pronounced as [dɨms].[42]

Facultative vowels

- /øː/ only exists in Southern Kurdish, represented by ⟨ö⟩. In Northern Kurdish, it is only present facultatively in loan words from Turkish, as it mostly merges with /oː/. The word öks (from Turkish ökse meaning 'clayish mud') is pronounced as either [øːks] or [oːks].[43]

- 'Short o' ([o]) is not common in Kurdish and exists mostly in loanwords from Turkish like komite, which is pronounced as [komiːˈtɛ].[44]

Glides and diphthongs

The glides [w], [j], and [ɥ] appear in syllable onsets immediately followed by a full vowel. All combinations except the last four are present in all three Kurdish dialects. If the word used as an example is unique to a dialect, the dialect is mentioned.

| IPA | Spelling | Example Word | Dialect Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern | Central | Southern | |||||

| [əw] | aw | şaw[45] | [ˈʃəw] | 'night' (Central Kurdish) | |||

| [ɑːw] | âw | çaw[45] | [ˈt͡ʃɑːw] | 'eye' (Central Kurdish) | |||

| [ɑːj] | ây | çay[45] | [ˈt͡ʃɑːj] | 'tea' | |||

| [ɛw] | ew | kew[46] | [ˈkɛw] | 'partridge' | |||

| [ɛj] | ey | peynja[45] | [pɛjˈnʒæ] [pɛjˈnʒɑː] |

'ladder' | |||

| [oːj] | oy | birôyn[45] | [bɪˈɾoːjn] | 'let's go' (Central Kurdish) | |||

| [uːj] | ûy | çûy[45] | [ˈt͡ʃuːj] | 'went' (Central Kurdish) | |||

| [ɑːɥ] | a | da[13] | [ˈdɑːɥ] | 'ogre' (Southern Kurdish) | |||

| [ʉːɥ] | ü | küa[13] | [ˈkʉːɥɑː] | 'mountain' (Southern Kurdish) | |||

| [ɛɥ] | e | tela[13] | [tɛɥˈlɑː] | 'stable' (Southern Kurdish) | |||

| [ɥɑː] | a | dat[13] | [dɥɑːt] | 'daughter' (Southern Kurdish) | |||

References

- Khan & Lescot (1970), pp. 3-7.

- Haig & Matras (2002), p. 5.

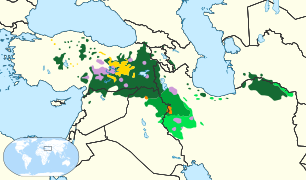

- The map shown is based on a map published by Le Monde Diplomatique in 2007.

- Thackston (2006a), pp. 1-2.

- Asadpour & Mohammadi (2014), p. 109.

- Khan & Lescot (1970), p. 5.

- Sedeeq (2017), p. 82.

- Rahimpour & Dovaise (2011), p. 75.

- Windfuhrt (2012), p. 597.

- Rahimpour & Dovaise (2011), pp. 75-76.

- Hamid (2015), p. 18.

- Campbell & King (2000), p. 899.

- Fattahi, Anonby & Gheitasi (2016).

- McCarus (1958), pp. 12.

- Fattah (2000), pp. 96-97.

- Fattah (2000), pp. 97-98.

- Gündoğdu (2016), pp. 61-62.

- Gündoğdu (2016), p. 65.

- "Kurdish language i. History of the Kurdish language". Iranicaonline. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- Thackston (2006b), pp. 2-4.

- Thackston (2006b), p. 2.

- Khan & Lescot (1970), p. 6.

- Asadpour & Mohammadi (2014), p. 114.

- "1.26 Pharyngeal substitution". Dialects of Kurdish. University of Manchester. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "1.27 Pharyngeal retention in 'animal'". Dialects of Kurdish. University of Manchester. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- Sedeeq (2017), pp. 80, 105–106.

- Khan & Lescot (1970), pp. 8-16.

- Thackston (2006a), p. 1.

- Thackston (2006b), pp. 1-2.

- Thackston (2006a), p. 7.

- Fattah (2000), pp. 110-122.

- Soane (1922), pp. 193-202.

- Fattah describes the sound as a voyelle brève antérieure ou centrale non arrondie (p. 119).

- Fattah describes the sound as a voyelle longue postérieure, d'aperture maximale, légèrement nasalisée. (p. 110)

- Fattah describes the sound as being the voyelle ultra-brève centrale très légèrement arrondie (p. 120).

- Fattah describes the sound as being the voyelle longue d'aperture minimale centrale arrondie (p. 114).

- Fattah describes the sound as being the voyelle postérieure arrondie (p. 111).

- Fattah describes the sound as being voyelle longue centrale arrondie (p. 116).

- Thackston (2006a), p. 3.

- Thackston (2006b), p. 1.

- Gündoğdu (2016), p. 62.

- Gündoğdu (2016), p. 61.

- Khan & Lescot (1970), p. 16.

- Soane (1922), p. 198.

- Rahimpour & Dovaise (2011), p. 77.

- Asadpour & Mohammadi (2014), p. 107.

Bibliography

- Asadpour, Hiwa; Mohammadi, Maryam (2014), A Comparative Study of Phonological System of Kurdish Varieties (PDF), Journal of Language and Cultural Education, pp. 108–109 & 113, ISSN 1339-4584, retrieved 29 October 2017

- Campbell, George L.; King, Gareth (2000), Compendium of the World's Languages

- Fattah, Ismaïl Kamandâr (2000), Les dialectes Kurdes méridionaux, Acta Iranica, ISBN 9042909188

- Fattahi, Mehdi; Anonby, Erik; Gheitasi, Mojtaba (2016), Is the labial-palatal approximant a phoneme in Southern Kurdish? (PDF), retrieved 2 December 2017

- Gündoğdu, Songül (2016), Remarks on Vowels and Consonants in Kurmanji, retrieved 14 December 2017

- Haig, Geoffrey; Matras, Yaron (2002), "Kurdish linguistics: a brief overview" (PDF), Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung, Berlin, 55 (1): 5, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017, retrieved 27 April 2013

- Hamid, Twana Saadi (2015), The Prosodic Phonology of Central Kurdish, Newcastle University

- Khan, Celadet Bedir; Lescot, Roger (1970), Grammaire Kurde (Dialecte kurmandji) (PDF), Paris: La librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient Adrien Maisonneuve, retrieved 28 October 2017

- Rahimpour, Massoud; Dovaise, Majid Saedi (2011), "A Phonological Contrastive Analysis of Kurdish and English" (PDF), International Journal of English Linguistics, 1 (2): 75, retrieved 19 November 2017

- McCarus, Ernest N. (1958), —A Kurdish Grammar (PDF), retrieved 11 June 2018

- Sedeeq, Dashne Azad (2017), Diachronic Study of English Loan Words in the Central Kurdish Dialect in Media Political Discourse (PDF), University of Leicester, p. 82

- Öpengin, Ergin; Haig, Geoffrey (2014), "Regional variation in Kurmanji: A preliminary classification of dialects", Kurdish Studies, 2, ISSN 2051-4883

- Soane, Ely Banister (1922), "Notes on the Phonology of Southern Kurmanji", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2

- Thackston, W.M. (2006a), —Sorani Kurdish— A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings (PDF), retrieved 29 October 2017

- Thackston, W.M. (2006b), —Kurmanji Kurdish— A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings (PDF), retrieved 18 December 2017

- Ludwig Windfuhr, Gernot (2012), The Iranian Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1131-4