Georg Wilhelm Steller

Georg Wilhelm Steller (10 March 1709 – 14 November 1746) was a German botanist, zoologist, physician and explorer, who worked in Russia and is considered a pioneer of Alaskan natural history.[1][2]

| ||||

|

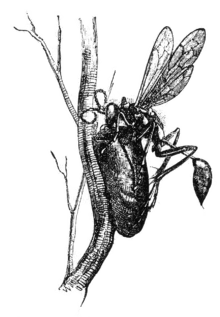

Several animals described by and named for Georg Steller, of whom no portrait is known to exist.

| ||||

Biography

Steller was born in Windsheim, near Nuremberg in Germany, son to a Lutheran cantor named Johann Jakob Stöhler (after 1715, Stöller), and studied at the University of Wittenberg. He then traveled to Russia as a physician on a troop ship returning home with the wounded. He arrived in Russia in November 1734. He met the naturalist Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt (1685–1735) at the Imperial Academy of Sciences. Two years after Messerschmidt's death, Steller married his widow and acquired notes from his travels in Siberia not handed over to the Academy.[3]

Steller knew about Vitus Bering's Second Kamchatka Expedition, which had left Saint Petersburg in February 1733. He volunteered to join it and was accepted. He then left St Petersburg in January 1738 with his wife, who decided to stay in Moscow and go no farther. Steller met Johann Georg Gmelin in Yeniseisk in January 1739. Gmelin recommended that Steller take his place in the planned exploration of Kamchatka. Steller embraced that role and finally reached Okhotsk and the main expedition in March 1740 as Bering's ships, the St. Peter and St. Paul, were nearing completion.

In September 1740, the expedition sailed to the Kamchatka Peninsula with Bering and his two expeditionary vessels sailing around the peninsula's south tip and up to Avacha Bay on the Pacific coast. Steller went ashore on the east coast of Kamchatka to spend the winter in Bolsherechye, where he helped to organize a local school and began exploring Kamchatka. When Bering summoned him to join the voyage in search of America and the strait between the two continents, serving in the role of scientist and physician, Steller crossed the peninsula by dog sled. After Bering's St. Peter was separated from its sister ship the St. Paul in a storm, Bering continued to sail east, expecting to find land soon. Steller, reading sea currents and flotsam and wildlife, insisted they should sail northeast. After considerable time lost, they turned northeast and made landfall in Alaska at Kayak Island on Monday 20 July 1741. Bering wanted to stay only long enough to take on fresh water. Steller argued Captain Bering into giving him more time for land exploration and was granted 10 hours.

During his ten hours on land Stellar noted the mathematical ratio of 10 years preparation for ten hours of investigation. While the crew never ever set foot on the mainland, Georg Steller is credited with being one of the first non-natives to have set foot upon Alaskan soil. The expedition never made mainland landfall because of a stubbornness and a "dull fear" They left with only a sketch of what they think the mainland would look like. On a remarkable journey, Steller became the first European naturalist to describe a number of North American plants and animals, including a jay later named Steller's jay.

Of the six species of birds and mammals that Steller discovered during the voyage, two are extinct (Steller's sea cow and the spectacled cormorant) and three are endangered or in severe decline (Steller's sea lion, Steller's eider and Steller's sea eagle). The sea cow, in particular, a massive northern relative of the dugong, lasted only 27 years after Steller discovered and named it, a limited population that quickly became victim of overhunting by the Russian crews that followed in Bering's wake.

Steller's jay is one of the few species named after Steller that is not currently endangered. In his brief encounter with the bird, Steller was able to deduce that the jay was kin to the American blue jay, a fact which seemed proof that Alaska was indeed part of North America.

Although Steller tried to treat the crew's growing scurvy epidemic with leaves and berries he had gathered, officers scorned his proposal. Steller and his assistant were some of the very few who did not suffer from the ailment. On the return journey, with only 12 members of the crew able to move and the rigging rapidly failing, the expedition was shipwrecked on what later became known as Bering Island. Almost half of the crew had perished from scurvy during the voyage. Steller nursed the survivors, including Bering, but the aging captain could not be saved and died. The remaining men made camp with little food or water, a situation made only worse by frequent raids by Arctic foxes. They hunted sea otters, sea lions, fur seals and sea cows to survive the winter.[4] Despite the hardships the crew endured, Steller studied the flora, fauna, and topography of the island in great detail. Of particular note were the only detailed behavioral and anatomical observations of Steller's sea cow, a large sirenian mammal that once ranged across the Northern Pacific during the Ice Ages, but whose surviving relict population was confined to the shallow kelp beds around the Commander Islands, and which was driven to extinction within 30 years of discovery by Europeans.

Based on these and other observations, Steller later wrote De Bestiis Marinis ('On the Beasts of the Sea'), describing the fauna of the island, including the northern fur seal, the sea otter, Steller's sea lion, Steller's sea cow, Steller's eider and the spectacled cormorant. Steller claimed the only recorded sighting of the marine cryptid Steller's sea ape.

In early 1742, the crew used salvaged material from the St. Peter to construct a new vessel to return to Avacha Bay and nicknamed it The Bering. Steller spent the next two years exploring the Kamchatka peninsula. Because of his sympathies for the native Kamchatkans, he was accused of fomenting rebellion and was recalled to Saint Petersburg. At one point he was put under arrest and made to return to Irkutsk for a hearing. He was freed and again turned west toward St. Petersburg, but along the way he came down with a fever and died at Tyumen.

His journals, which reached the Academy and were later published by Peter Simon Pallas, were used by other explorers of the North Pacific, including Captain Cook.

Discoveries and namesakes

Georg Steller described a number of animals and plants, some of which bear his name, either in the common name or scientific:

- Steller's eider (Polysticta stelleri)

- Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri)

- Sea otter (Enhydra lutris)

- Steller's sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus)

- Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)

- Steller's sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus)

- Gumboot chiton (Cryptochiton stelleri)

- Hoary mugwort (Artemisia stelleriana)

- Stellera L. (Thymelaeaceae)

- Stellerite (a mineral in the zeolite group)

There is a secondary school in Anchorage, Alaska named after him: Steller Secondary School.

References

- Evans, Howard Ensign. Edward Osborne Wilson (col.) The Man who Loved Wasps: A Howard Ensign Evans Reader. in: Evans, Mary Alice. Big Earth Publishing, 2005. pp. 169. ISBN 1555663508

- Nuttall, Mark. Encyclopedia of the Arctic. Routledge, 2012. pp. 1953. ISBN 1579584365

- Egerton, Frank N. (2008). "A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 27: Naturalists Explore Russia and the North Pacific During the 1700s". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 89 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1890/0012-9623(2008)89[39:AHOTES]2.0.CO;2.

- Littlepage, Dean. Steller's Island: Adventures of a Pioneer Naturalist in Alaska.

- IPNI. Steller.

Further reading

- Leonhard Stejneger – Georg Wilhelm Steller, the pioneer of Alaskan natural history. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1936.

- G. W. Steller – Reise von Kamtschatka nach Amerika mit dem Commandeur-Capitän Bering : ein Pendant zu dessen Beschreibung von Kamtschatka. St Petersbrug, 1793. Full text

- Georg Steller – Journal of a Voyage with Bering, 1741–1742 edited by O. Frost. Stanford University Press,1993. ISBN 0-8047-2181-5

- Walter Miller and Jennie Emerson Miller, translators – De Bestiis Marinis, or, The Beasts of the Sea) in an appendix to The Fur Seals and Fur-Seal Islands of the North Pacific Ocean, edited by David Starr Jordan, Part 3 (Washington, 1899), pp. 179–218

- Andrei Bronnikov (2009). Species Evanescens [Ischezayushchi vid] (Russian Edition). Reflections, ISBN 978-90-79625-02-4 (a book of poetry inspired by dramatic events of Steller's life).

- Ann Arnold (2008). Sea Cows, Shamans, and Scurvy Alaska's First Naturalist: Georg Wilhelm Steller. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Marcus Köhler: "Völker-Beschreibung". Die ethnographische Methodik Georg Wilhelm Stellers (1709–1746) im Kontext der Herausbildung der "russischen" ėtnografija. Saarbrücken 2008. (about Steller's importance for the development of modern ethnography as a science)

- Dean Littlepage (2006). Steller's Island: Adventures of a Pioneer Naturalist in Alaska. The Mountaineer's Books. ISBN 1-59485-057-7

- Barbara and Richard Mearns – Biographies for Birdwatchers ISBN 0-12-487422-3

- Corey Ford, Where the Sea Breaks its Back, 1966. Anchorage: Alaska Northwest Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0-88240-394-6

- Steller's 1741 expedition from Kamchatka is covered in Orcutt Frost's Bering: the Russian discovery of America (Yale University Press, 2004).

- Steller is the subject of the second section of W. G. Sebald's book-length poem, After Nature (2002).

- A somewhat fictionalized account of Steller's time with Bering is contained in James A. Michener's, Alaska.

External links

- (in Russian) Commander (Komandorskie) Islands

- (in Russian) Steller, Georg Wilhelm

- (in Russian) Poetry on Steller

- (in German) German National Geographic magazine about the diary of Steller

- Extracts from De Bestiis Marinis, or, The Beasts of the Sea (1751)