King vulture

The king vulture (Sarcoramphus papa) is a large bird found in Central and South America. It is a member of the New World vulture family Cathartidae. This vulture lives predominantly in tropical lowland forests stretching from southern Mexico to northern Argentina. It is the only surviving member of the genus Sarcoramphus, although fossil members are known.

| King vulture | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Cathartidae |

| Genus: | Sarcoramphus Duméril, 1805 |

| Species: | S. papa |

| Binomial name | |

| Sarcoramphus papa | |

| |

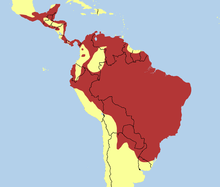

| The distribution of the king vulture | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Vultur papa Linnaeus, 1758 | |

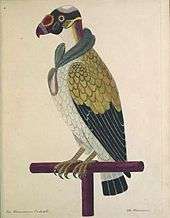

Large and predominantly white, the king vulture has gray to black ruff, flight, and tail feathers. The head and neck are bald, with the skin color varying, including yellow, orange, blue, purple, and red. The king vulture has a very noticeable orange fleshy caruncle on its beak. This vulture is a scavenger and it often makes the initial cut into a fresh carcass. It also displaces smaller New World vulture species from a carcass. King vultures have been known to live for up to 30 years in captivity.

King vultures were popular figures in the Mayan codices as well as in local folklore and medicine. Although currently listed as least concern by the IUCN, they are decreasing in number, due primarily to habitat loss.

Etymology, taxonomy and systematics

The king vulture was originally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae as Vultur papa,[2] the type specimen originally collected in Suriname.[3] It was reassigned to the genus Sarcoramphus in 1805 by French zoologist André Marie Constant Duméril. The generic name is a New Latin compound formed from the Greek words σάρξ (sarx, "flesh", the combining form of which is σαρκο-) and ῥάμφος (rhamphos, "crooked beak of bird of prey").[4] The genus name is often misspelled as Sarcorhamphus, improperly retaining the Greek rough breathing despite agglutination with the previous word-element. The bird was also assigned to the genus Gyparchus by Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger in 1841, but this classification is not used in modern literature since Sarcoramphus has priority as the earlier name.[5] The species name is derived from Latin word papa "bishop", alluding the bird's plumage resembling the clothing of one.[6] The king vulture's closest living relative is the Andean condor, Vultur gryphus.[7] Some authors have even put these species in a separate subfamily from the other New World vultures, though most authors consider this subdivision unnecessary.[7]

There are two theories on how the king vulture earned the "king" part of its common name. The first is that the name is a reference to its habit of displacing smaller vultures from a carcass and eating its fill while they wait.[8] An alternative theory reports that the name is derived from Mayan legends, in which the bird was a king who served as a messenger between humans and the gods.[9] This bird was also known as the "white crow" by the Spanish in Paraguay.[10] It was called cozcacuauhtli in Nahuatl, derived from cozcatl "collar" and cuauhtli "bird of prey".[11]

The exact systematic placement of the king vulture and the remaining six species of New World vultures remains unclear.[12] Though both are similar in appearance and have similar ecological roles, the New World and Old World vultures evolved from different ancestors in different parts of the world. Just how different the two are is currently under debate, with some earlier authorities suggesting that the New World vultures are more closely related to storks.[13] More recent authorities maintain their overall position in the order Falconiformes along with the Old World vultures[14] or place them in their own order, Cathartiformes.[15] The South American Classification Committee has removed the New World vultures from Ciconiiformes and instead placed them in Incertae sedis, but notes that a move to Falconiformes or Cathartiformes is possible.[12] Like other New World vultures, the king vulture has a diploid chromosome number of 80.[16]

Fossil record and evolution

The genus Sarcoramphus, which today contains only the king vulture, had a wider distribution in the past. The Kern vulture (Sarcoramphus kernense), lived in southwestern North America during the mid-Pliocene (Piacenzian), some 3.5–2.5 million years ago). It was a little-known component of the Blancan/Delmontian faunal stages. The only material is a broken distal humerus fossil, found at Pozo Creek, Kern County, California. As per Loye H. Miller's original description, "[c]ompared with [S. papa] the type conforms in general form and curvature except for its greater size and robustness."[17] The large span in time between the existence of the two species suggests that the Kern vulture might be distinct, but as the fossil is somewhat damaged and rather non-diagnostic, even assignment to this genus is not completely certain.[18] During the Late Pleistocene, another species probably assignable to the genus, Sarcoramphus fisheri, occurred in Peru.[19] A supposed king vulture relative from Quaternary cave deposits on Cuba turned out to be bones of the eagle-sized hawk Buteogallus borrasi (formerly in Titanohierax).[20]

Little can be said of the evolutionary history of the genus, mainly because remains of other Neogene New World vultures are usually younger or even more fragmentary. The teratorns held sway over the ecological niche of the extant group especially in North America. The Kern vulture seems to slightly precede the main bout of the Great American Interchange, and it is notable that the living diversity of New World vultures seems to have originated in Central America.[17] The Kern vulture would therefore represent a northwards divergence possibly sister to the S. fisheri – S. papa lineage. The fossil record, though scant, supports the theory that the ancestral king vultures and South American condors separated at least some 5 mya.[21]

Bartram's "painted vulture"

A "painted vulture" ("Sarcoramphus sacra" or "S. papa sacra") is described in William Bartram's notes of his travels in Florida during the 1770s. This bird's description matches the appearance of the king vulture except that it had a white, not black, tail.[22] Bartram describes the bird as being relatively common and even claimed to have collected one.[22] However, no other naturalists record the painted vulture in Florida and sixty years after the sighting its validity began to be questioned, leading to what John Cassin described as the most inviting problem in North American ornithology.[22] An independent account and painting was made of a similar bird by Eleazar Albin in 1734.[23]

While most early ornithologists defended Bartram's honesty, Joel Asaph Allen argued that the painted vulture was mythical and that Bartram mixed elements of different species to create this bird.[22] Allen pointed out that the birds' behavior, as recorded by Bartram, is in complete agreement with the caracara's.[22] For example, Bartram observed the birds following wildfires to scavenge for burned insects and box turtles. Such behavior is typical of caracaras, but the larger and shorter-legged king vultures are not well adapted for walking. The northern crested caracara (Caracara cheriway) was believed to be common and conspicuous in Bartram's days, but it is notably absent from Bartram's notes if the painted vulture is accepted as a Sarcoramphus.[22] However, Francis Harper argued that the bird could, as in the 1930s, have been rare in the area Bartram visited and could have been missed.[22]

Harper noticed that Bartram's notes were considerably altered and expanded in the printed edition, and the detail of the white tail appeared in print for the first time in this revised account. Harper believed that Bartram could have tried to fill in details of the bird from memory and got the tail coloration wrong.[22] Harper and several other researchers have attempted to prove the former existence of the king vulture, or a close relative, in Florida at this late date, suggesting that the population was in the process of extinction and finally disappeared during a cold spell.[22][24] Additionally, William McAtee, noting the tendency of birds to form Floridian subspecies, suggested that the white tail could be a sign that the painted vulture was a subspecies of the king vulture.[25]

Description

_-_Weltvogelpark_Walsrode_2013-01.jpg)

Excluding the two species of condors, the king vulture is the largest of the New World vultures. Its overall length ranges from 67 to 81 cm (26–32 in) and its wingspan is 1.2 to 2 m (4–7 ft). Its weight ranges from 2.7 to 4.5 kg (6–10 lb).[9][26] An imposing bird, the adult king vulture has predominantly white plumage, which has a slight rose-yellow tinge to it.[27] In stark contrast, the wing coverts, flight feathers and tail are dark grey to black, as is the prominent thick neck ruff.[3] The head and neck are devoid of feathers, the skin shades of red and purple on the head, vivid orange on the neck and yellow on the throat.[28] On the head, the skin is wrinkled and folded, and there is a highly noticeable irregular golden crest attached on the cere above its orange and black bill;[3] this caruncle does not fully form until the bird's fourth year.[29]

The king vulture has, relative to its size, the largest skull and braincase, and strongest bill, of the New World vultures.[18] This bill has a hooked tip and a sharp cutting edge.[6] The bird has broad wings and a short, broad, and square tail.[27] The irises of its eyes are white and bordered by bright red sclera.[3] Unlike some New World vultures, the king vulture lacks eyelashes.[30] It also has gray legs and long, thick claws.[27]

The vulture is minimally sexually dimorphic, with no difference in plumage and little in size between males and females.[3] The juvenile vulture has a dark bill and eyes, and a downy, gray neck that soon begins to turn the orange of an adult. Younger vultures are a slate gray overall, and, while they look similar to the adult by the third year, they do not completely molt into adult plumage until they are around five or six years of age.[27] Jack Eitniear of the Center for the Study of Tropical Birds in San Antonio, Texas reviewed the plumage of birds in captivity of various ages and found that ventral feathers were the first to begin turning white from two years of age onwards, followed by wing feathers, until the full adult plumage was achieved. The final immature stages being a scattered black feathers in the otherwise white lesser wing coverts.[31]

The vulture's head and neck are featherless as an adaptation for hygiene, though there are black bristles on parts of the head; this lack of feathers prevents bacteria from the carrion it eats from ruining its feathers and exposes the skin to the sterilizing effects of the sun.[6][32]

Dark-plumaged immature birds may be confused with turkey vultures, but soar with flat wings, while the pale plumaged adults could feasibly be confused with the wood stork,[33] although the latter's long neck and legs allow for easy recognition from afar.[34]

Distribution and habitat

The king vulture inhabits an estimated 14 million square kilometres (5,400,000 sq mi) between southern Mexico and northern Argentina.[35] In South America, it does not live west of the Andes,[29] except in western Ecuador,[36] north-western Colombia and far north-western Venezuela.[37] It primarily inhabits undisturbed tropical lowland forests as well as savannas and grasslands with these forests nearby.[38] It is often seen near swamps or marshy places in the forests.[10] This bird is often the most numerous or only vulture present in primary lowland forests in its range, but in the Amazon rainforest it is typically outnumbered by the greater yellow-headed vulture, while typically outnumbered by the lesser yellow-headed, turkey and American black vulture in more open habitats.[39] King vultures generally do not live above 1,500 m (5,000 ft), although are found in places at 2,500 m (8,000 ft) altitude east of the Andes, and have been rarely recorded up to 3,300 m (11,000 ft)[26] They inhabit the emergent forest level, or above the canopy.[3] Pleistocene remains have been recovered from Buenos Aires Province in central Argentina, over 700 km (450 miles) south of its current range, giving rise to speculation on the habitat there at the time which had not been thought to be suitable.[40]

Ecology and behavior

The king vulture soars for hours effortlessly, only flapping its wings infrequently.[34][41] While in flight, its wings are held flat with slightly raised tips, and from a distance the vulture can appear to be headless while in flight.[42] Its wing beats are deep and strong.[27] Birds have been observed engaging in tandem flight on two occasions in Venezuela by naturalist Marsha Schlee, who has proposed it could be a part of courtship behaviour.[43]

Despite its size and gaudy coloration, this vulture is quite inconspicuous when it is perched in trees.[42] While perched, it holds its head lowered and thrust forward.[26] It is non-migratory and, unlike the turkey, lesser yellow-headed and American black vulture, it generally lives alone or in small family groups.[44] Groups of up to 12 birds have been observed bathing and drinking in a pool above a waterfall in Belize.[45] One or two birds generally descend to feed at a carcass, although occasionally up to ten or so may gather if there is significant amount of food.[3] King vultures have lived up to 30 years in captivity, though a male transferred from the Sacramento Zoo to the Queens Zoo is over 47 years old. Their lifespan in the wild is unknown.[9] This vulture uses urohidrosis, defecating on its legs, to lower its body temperature. Despite its bill and large size, it is relatively unaggressive at a kill.[3] The king vulture lacks a voice box, although it can make low croaking noises and wheezing sounds in courtship, and bill-snapping noises when threatened.[26] Its only natural predators are snakes, which will prey upon the vulture's eggs and young, and large cats such as jaguars, which may surprise and kill an adult vulture at a carcass.[46]

Breeding

.jpg)

The reproductive behaviour of the king vulture in the wild is poorly known, and much knowledge has been gained from observing birds in captivity,[47] particularly at the Paris Menagerie.[48] An adult king vulture sexually matures when it is about four or five years old, with females maturing slightly earlier than males.[49] The birds mainly breed during the dry season.[46] A king vulture mates for life and generally lays a single unmarked white egg in its nest in a hollow in a tree.[27] To ward off potential predators, the vultures keep their nests foul-smelling.[47] Both parents incubate the egg for the 52 to 58 days before it hatches. If the egg is lost, it will often be replaced after about six weeks. The parents share incubating and brooding duties until the chick is about a week old, after which they often stand guard rather than brood. The young are semi-altricial—they are helpless when born but are covered in downy feathers (truly altricial birds are born naked), and their eyes are open at birth. Developing quickly, the chicks are fully alert by their second day, and able to beg and wriggle around the nest, and preen themselves and peck by their third day. They start growing their second coat of white down by day 10, and stand on their toes by day 20. From one to three months of age, chicks walk around and explore the vicinity of the nest, and take their first flights at about three months of age.[48]

Feeding

The king vulture eats anything from cattle carcasses to beached fish and dead lizards. Principally a carrion eater, there are isolated reports of it killing and eating injured animals, newborn calves and small lizards.[26] Although it locates food by vision, the role smell has in how it specifically finds carrion has been debated. Consensus has been that it does not detect odours, and instead follows the smaller turkey and greater yellow-headed vultures, which do have a sense of smell, to a carcass,[3][50] but a 1991 study demonstrated that the king vulture could find carrion in the forest without the aid of other vultures, suggesting that it locates food using an olfactory sense.[51] The king vulture primarily eats carrion found in the forest, though it is known to venture onto nearby savannas in search of food. Once it has found a carcass, the king vulture displaces the other vultures because of its large size and strong bill.[3] However, when it is at the same kill as the larger Andean condor, the king vulture always defers to it.[52] Using its bill to tear, it makes the initial cut in a fresh carcass. This allows the smaller, weaker-beaked vultures, which can not open the hide of a carcass, access to the carcass after the king vulture has fed.[3] The vulture's tongue is rasp-like, which allows it to pull flesh off of the carcass's bones.[32] Generally, it only eats the skin and harder parts of the tissue of its meal.[46] The king vulture has also been recorded eating fallen fruit of the moriche palm when carrion is scarce in Bolívar state, Venezuela.[53]

Conservation

This bird is a species of least concern to the IUCN,[1] with an estimated range of 14 million square kilometres (5,400,000 sq mi) and between 10,000 and 100,000 wild individuals. However, there is evidence that suggests a decline in population, though it is not significant enough to cause it to be listed.[35] This decline is due primarily to habitat destruction and poaching.[44] Although distinctive, its habit of perching in tall trees and flying at altitude render it difficult to monitor.[3]

Relationship with humans

The king vulture is one of the most common species of birds represented in the Maya codices.[54] Its glyph is easily distinguishable by the knob on the bird's beak and by the concentric circles that make up the bird's eyes.[54] Sometimes the bird is portrayed as a god with a human body and a bird head.[54] According to Maya mythology, this god often carried messages between humans and the other gods.[46] It may also be used to represent Cozcacuauhtli, the thirteenth day of the month in the Aztec calendar (13 Reed). An ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata) was also considered to be the bird depicted, but the hooked bill and wattle point to the raptor.[11]

The bird's blood and feathers were also used to cure diseases.[32] The king vulture is also a popular subject on the stamps of the countries within its range. It appeared on a stamp for El Salvador in 1963, Belize in 1978, Guatemala in 1979, Honduras in 1997, Bolivia in 1998, and Nicaragua in 1999.[55]

Because of its large size and beauty, the king vulture is an attraction at zoos around the world. The king vulture is one of several bird species with an AZA studbook, which is kept by Shelly Collinsworth of the Fort Worth Zoo.[56]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Sarcoramphus papa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 86.

V. naribus carunculatis, vertice colloque denudate

- Houston, D.C. (1994). "Family Cathartidae (New World vultures)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (') (eds.). Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl of Handbook of the Birds of the World. Barcelona: Lynx edicions. pp. 24–41. ISBN 84-87334-15-6.

- Liddell, Henry George; Robert Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Peterson, Alan P. (23 December 2007). "Richmond Index – Genera Aaptus – Zygodactylus". The Richmond Index. Division of Birds at the National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Likoff, Laurie (2007). "King Vulture". The Encyclopedia of Birds. Infobase Publishing. pp. 557–60. ISBN 978-0-8160-5904-1.

- Amadon, Dean (1977). "Notes on the Taxonomy of Vultures" (PDF). The Condor. The Condor, Vol. 79, No. 4. 79 (4): 413–16. doi:10.2307/1367720. JSTOR 1367720. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Wood, John George (1862). The illustrated natural history. London: Routledge, Warne and Routledge. pp. 15–17.

- "King Vulture". National Geographic. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Wood, John George (1862). The illustrated natural history. Oxford University. ISBN 0-19-913383-2.

- Diehl, Richard A.; Berlo, Janet Catherine (1989). Mesoamerica after the decline of Teotihuacan, A.D. 700–900, Parts 700–900. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-88402-175-0.

- Remsen, J. V., Jr.; C. D. Cadena; A. Jaramillo; M. Nores; J. F. Pacheco; M. B. Robbins; T. S. Schulenberg; F. G. Stiles; D. F. Stotz & K. J. Zimmer. 2007. A classification of the bird species of South America. Archived 2009-03-02 at the Wayback Machine South American Classification Committee. Retrieved on 15 October 2007

- Sibley, Charles G.; Monroe, Burt L.. (1990). Distribution and Taxonomy of the Birds of the World. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04969-2. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- Sibley, Charles G., and Ahlquist, Jon E.. 1991. Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: A Study in Molecular Evolution. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04085-7. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- Ericson, Per G. P.; Anderson, Cajsa L.; Britton, Tom; Elżanowski, Andrzej; Johansson, Ulf S.; Kallersjö, Mari; Ohlson, Jan I.; Parsons, Thomas J.; Zuccon, Dario; Mayr, Gerald (2006). "Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils" (PDF). Biology Letters. 2: 543–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523. PMC 1834003. PMID 17148284. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-08.

- Tagliarini, Marcella Mergulhão; Pieczarka, Julio Cesar; Nagamachi, Cleusa Yoshiko; Rissino, Jorge; de Oliveira, Edivaldo Herculano C. (2009). "Chromosomal analysis in Cathartidae: distribution of heterochromatic blocks and rDNA, and phylogenetic considerations". Genetica. 135 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1007/s10709-008-9278-2. PMID 18504528.

- Miller, Loye H. (1931). "Bird Remains from the Kern River Pliocene of California" (PDF). The Condor. 33 (2): 70–72. doi:10.2307/1363312. JSTOR 1363312.

- Fisher, Harvey L. (1944). "The skulls of the Cathartid vultures" (PDF). The Condor. 46 (6): 272–296. doi:10.2307/1364013. JSTOR 1364013.

- Wilbur, Sanford (1983). Vulture Biology and Management. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-520-04755-9.

- Suárez, William (2001). "A Re-evaluation of Some Fossils Identified as Vultures (Aves: Vulturidae) from Quaternary Cave Deposits of Cuba" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 37 (1–2): 110–111. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-01.

- Wilbur, Sanford (1983). Vulture Biology and Management. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-520-04755-9.

- Harper, Francis (October 1936). "The Vutlur sacra of William Bartram" (PDF). Auk. Lancaster, PA: American Ornithologist’s Union. 53 (4): 381–392. doi:10.2307/4078256. JSTOR 4078256. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- Snyder, N. F. R.; Fry, J. T. (2013). "Validity of Bartram's Painted Vulture". Zootaxa. 3613 (1): 61–82. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3613.1.3. PMID 24698902.

- Day, David (1981): The Doomsday Book of Animals: Ebury, London/Viking, New York. ISBN 0-670-27987-0

- McAtee, William Lee (January 1942). "Bartram's Painted Vulture" (PDF). Auk. Lancaster, PA: American Ornithologist’s Union. 59 (1): 104. doi:10.2307/4079172. JSTOR 4079172. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A (2001). Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 88, 315–16. ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7.

- Howell, Steve N.G.; Webb, Sophie (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 0-19-854012-4.

- Terres, J. K. (1980). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York, NY: Knopf. p. 959. ISBN 0-394-46651-9.

- Gurney, John Henry (1864). A descriptive catalogue of the raptorial birds in the Norfolk and Norwich museum. Oxford University. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Fisher, Harvey I. (March 1943). "The Pterylosis of the King Vulture" (PDF). Condor. The Condor, Vol. 45, No. 2. 45 (2): 69–73. doi:10.2307/1364380. JSTOR 1364380. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Eitniear, Jack Clinton (1996). "Estimating age classes in king vultures (Sarcoramphus papa) using plumage coloration" (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 30 (1): 35–38. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Sarcoramphus papa". Who Zoo. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Hilty, Stephen L.; Brown, William L.; Brown, Bill (1986). A guide to the birds of Colombia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-691-08372-X.

- Henderson, Carrol L.; Adams, Steve; Skutch, Alexander F. (2010). Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide. University of Texas Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-292-71965-1.

- "Species factsheet: Sarcoramphus papa". BirdLife International. 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Ridgely, Robert; Greenfield, Paul (2001). Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Cornell University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-8014-8721-8.

- Restall, Robin; Rodner, Clemencia; Lentino, Miguel (2006). Birds of Northern South America: An Identification Guide. Vol. 2. Christopher Helm. p. 68. ISBN 0-7136-7243-9.

- Brown, Leslie (1976). Birds of Prey: Their biology and ecology. Hamlyn. p. 59. ISBN 0-600-31306-9.

- Restall, Robin; Rodner, Clemencia; Lentino, Miguel (2006). Birds of Northern South America: An Identification Guide. Vol. 1. Christopher Helm. pp. 80–83. ISBN 0-7136-7242-0.

- Noriega, Jorge I.; Areta, Juan I. (2005). "First record of Sarcoramphus Dumeril 1806 (Ciconiiformes: Vulturidae) from the Pleistocene of Buenos Aires province, Argentina" (PDF). Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 20 (1–2 (SI)): 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2005.05.004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Schulenberg, Thomas S. (2007). Birds of Peru. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-691-13023-1.

- Ridgely, Robert S.; Gwynne, John A. Jr. (1989). A Guide to the Birds of Panama with Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Honduras (Second ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-691-02512-6.

- Schlee, Marsha (2001). "First record of tandem flying in the King Vulture (Sarcoramphus papa)" (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 35 (3): 263–64. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Bellinger, Jack (March 25, 1997). "King Vulture AZA Studbook". Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- Baker, Aaron J.; Whitacre, David F.; Aguirre, Oscar (1996). "Observations of king vultures (Sarcoramphus papa) drinking and bathing". Journal of Raptor Research. 30 (4): 246–47.

- Ormiston, D. "Sarcoramphus papa". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- de Roy, Tui (1998). "King of the Jungle". International Wildlife (28): 52–57. ISSN 0020-9112.

- Schlee, Marsha A. (1994). "Reproductive Biology in King Vultures at the Paris Menagerie". International Zoo Yearbook. 33 (1): 159–75. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1994.tb03570.x.

- Grady, Wayne (1997). Vulture: Nature's Ghastly Gourmet. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. p. 47. ISBN 0-87156-982-5.

- Beason, Robert C. (2003). "Through a Birds Eye: Exploring Avian Sensory Perception" (PDF). Bird Strike Committee USA/Canada, 5th Joint Annual Meeting, Toronto, ONT. University of Nebraska. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Lemon, William C (December 1991). "Foraging behavior of a guild of Neotropical vultures" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 103 (4): 698–702. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- "Ecology of Condors". Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- Schlee, Marsha (2005). "King vultures (Sarcoramphus papa) forage in moriche and cucurit palm stands" (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 39 (4): 458–61. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Tozzer, Alfred Marston; Glover Morrill Allen (1910). Animal Figures in the Maya Codices. Harvard University.

- "King Vulture". Bird Stamps. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "Vulture, King Studbook". AZA website. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2010. (subscription required)

External links

- King vulture videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- King vulture photo gallery (6 photos) Photo-High Res

- Stamps (for Belize, Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua) with RangeMap