National Zoological Park (United States)

The National Zoological Park, commonly known as the National Zoo, is one of the oldest zoos in the United States. It is part of the Smithsonian Institution and does not charge admission. Founded in 1889, its mission is to "provide engaging experiences with animals and create and share knowledge to save wildlife and habitats".[5]

Front entrance | |

| Date opened | May 6, 1889[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | 3001 Connecticut Ave. NW, Rock Creek Park, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°55′52″N 77°02′59″W |

| Land area | Zoo: 163 acres (66 ha)[2] SCBI: 3,200-acre (1,300 ha)[3] |

| No. of animals | Zoo: 2,000[2] SCBI: 30–40 endangered species[3] |

| No. of species | 400[2] |

| Memberships | AZA[4] |

| Major exhibits | Amazonia, Asia Trail, Giant Panda Habitat, Great Ape House, Think Tank |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | nationalzoo |

The National Zoo has two campuses. The first is a 163-acre (66 ha) urban park located at Rock Creek Park in Northwest Washington, D.C., 20 minutes from the National Mall by MetroRail.[6] The other campus is the 3,200-acre (1,300 ha) Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI; formerly known as the Conservation and Research Center) in Front Royal, Virginia. On this land, there are 180 species of trees, 850 species of woody shrubs and herbaceous plants, 40 species of grasses, and 36 different species of bamboo.[7] The SCBI is a non-public facility devoted to training wildlife professionals in conservation biology and to propagating rare species through natural means and assisted reproduction. The National Zoo is accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA).

The two facilities host about 2,700 animals of 390 different species.[8] About one-fifth of them are endangered or threatened. Most species are on exhibit at the Rock Creek Park campus.[9] The best-known residents are the giant pandas, but the zoo is also home to birds, great apes, big cats, Asian elephants, insects, amphibians, reptiles, aquatic animals, small mammals and many more. The SCBI facility houses between 30 and 40 endangered species at any given time depending on research needs and recommendations from the zoo and the conservation community.[3] The zoo was one of the first to establish a scientific research program.[7] Because it is a part of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Zoo receives federal appropriations for operating expenses. A new master plan for the park was introduced in 2008 to upgrade the park's exhibits and layout.

The National Zoo is open every day of the year except for December 25 (Christmas Day).

History

_(18431191142).jpg)

The zoo first started as the National Museum's Department of Living Animals in 1886.[10] By an act of Congress on March 2, 1889,[11][12][13] for "the advancement of science and the instruction and recreation of the people", the National Zoo was created. In 1890, it became a part of the Smithsonian Institution. Three well-known individuals drew up plans for the zoo: Samuel Langley, third Secretary of the Smithsonian; William Temple Hornaday, noted conservationist and head of the Smithsonian's vertebrate division; and Frederick Law Olmsted, the premier landscape architect of his day. William T. Hornaday was the park's first director and curator of all 185 animals when the park was first opened and took office on May 6, 1889.[10][14] Together, they designed a new zoo to exhibit animals for the public and to serve as a refuge for wildlife, such as bison and beaver, which were rapidly vanishing from North America.[15]

For the first 50 years, the National Zoo, like most zoos around the world, focused on exhibiting one or two representative exotic animal species. The number of many species in the wild began to decline drastically because of human activities. In 1899, the Kansas frontiersman Charles "Buffalo" Jones captured a bighorn sheep for the zoo.[16] The fate of animals and plants became a pressing concern. Many of these species were favorite zoo animals, such as elephants and tigers; hence the staff began to concentrate on the long-term management and conservation of entire species.[15]

In the mid-1950s, the zoo hired its first full-time permanent veterinarian, reflecting a priority placed on professional health care for the animals. In 1958, Friends of the National Zoo (FONZ) was founded. The citizen group's first accomplishment was to persuade Congress to fund the zoo's budget entirely through the Smithsonian; previously, the zoo's budget was divided between appropriations for the Smithsonian and the District of Columbia. Congressional funding placed the zoo on a firmer financial base, allowing for a period of growth and improvement. In 2006, Congress approved an additional $14.6 million for renovations in both facilities.[7] FONZ incorporated as a nonprofit organization and turned its attention to developing education and volunteer programs, supporting these efforts from its operation of concessions at the zoo, and expanding community support for the zoo through a growing membership[15] which annually raises between $4 million and $8 million for the zoo.[7]

In the early 1960s, the zoo turned its attention to breeding and studying threatened and endangered species. Although some zoo animals had been breeding and raising young, it was not understood why some species did so successfully while others did not. In 1965, the zoo created the zoological research division to study the reproduction, behavior, and ecology of zoo species, and to learn how best to meet the needs of the animals.[15]

In 1975, the zoo established the Conservation and Research Center (CRC). In 2010, the complex was renamed the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI), a title also used as an umbrella term for the scientific endeavors that take place on both campuses. On 3,200 acres (13 km2) in the Virginia countryside, rare species, such as Mongolian wild horses, scimitar-horned oryx, maned wolves, cranes, and others live and breed in spacious surroundings. SCBI's modern efforts emphasize reproductive physiology, analysis of habitat and species relationships, genetics, husbandry and the training of conservation scientists.[15]

The zoo's last hippopotamus, Happy, was transferred to Milwaukee County Zoo in 2009 to make space for Elephant Trails.[17]

Modern status

Expanding knowledge about the needs of zoo animals and commitment to their well being has changed the look of the National Zoo. Today, animals live in natural groupings rather than individually. Rare and endangered species, such as golden lion tamarins, Sumatran tigers, and sarus cranes, breed and raise their young – showing the success of the zoo's conservation and research programs.[15] The zoo's research team studies animals both in the wild and at the zoo. Its research encompasses reproductive biology, conservation biology, biodiversity monitoring, veterinary medicine, nutrition, behavior, ecology, and bird migration.[7]

The National Zoo has developed public-education programs to help students, teachers and families explore the intricacies of the animal world. The zoo also designed specialized programs to train wildlife professionals from around the world and to form a network to provide crucial support for international conservation. The National Zoo is at the forefront of the use of web technology and programming to expand its programs to an international virtual audience.[15]

The National Zoo has been the home to giant pandas since Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing arrived at the zoo in 1972. Since 2000, Mei Xiang and Tian Tian also lived there. On July 9, 2005, Mei Xiang gave birth to Tai Shan, who went to China in February 2010. On August 23, 2013, Mei Xiang gave birth to Bao Bao, who went to China in February 2017; upon her arrival she began participating in the species breeding program. On August 22, 2015, Mei Xiang gave birth to Bei Bei, who said farewell to The National Zoo in November 2019.[18] Due to an agreement with the China Wildlife Conservation Association, all giant panda born in the zoo, must relocate to China upon turning 4 years old.[15] Plans for the future include modernizing the zoo's aging facilities and expanding its education, research and conservation efforts in Washington, Virginia and in the wild. As part of a 10-year renewal program, Asia Trail – a series of habitats for seven Asian species including sloth bears, red pandas, and clouded leopards – was created. Elephant Trails, opened in 2013, provides a new home for the zoo's Asian elephants. Kids' Farm exhibit, opened in 2004, was slated for closure in 2011 but is to remain open for another 10 years following a donation to the exhibit.[15][19]

The zoo, which is supported by tax revenues and open to everyone, attracts 2 million visitors per year, according to the Washington Post in 2005.[20]

The National Zoo has a Federal Law Enforcement Agency deployed on its grounds: the National Zoological Park Police (NZPP), which consists of full-time Law Enforcement Officers. The NZPP is an agency that has been recognized by the United States Congress and is one of five original police agencies within the District of Columbia with full police powers. They work very closely with the Metropolitan Police Department, the United States Park Police, Department of State, Capital Police, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Defense. The agency is considered the first line of defense in the event of any crisis.[21]

Dennis W. Kelly was named director of the zoo on February 15, 2010, overseeing both campuses. Kelly succeeded John Berry, who was the National Zoo director for three years until February 2009, when he resigned to become the director of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management under the Obama Administration. Steven Monfort, the zoo's associate director for conservation and science, served as the acting director between February 2009 and February 2010. Kelly retired as the zoo's director in November 2017, Steven Monfort was named acting director.[22]

Exhibits

Giant Panda Habitat

The zoo's Giant Panda Habitat features three outdoor areas with animal enrichment, as well as an indoor area with a rocky outcrop, a waterfall, and viewing areas. The zoo's pandas, named Mei Xiang and Tian Tian, are on loan from the China Wildlife Conservation Association, and will live at the zoo until 2020.[19] They are the focus of a research, conservation, and breeding program that aims to preserve the species. Mei Xiang and Tian Tian successfully had a male cub, named Tai Shan, in 2005. Tai Shan currently lives at the Bifengxia Panda Base in Sichuan, China, taking part in Bifengxia's breeding program. On September 16, 2012, Mei Xiang gave birth to another cub, but the cub died six days after its birth. On August 23, 2013, Mei Xiang gave birth to two cubs; one, a female named Bao Bao, survived, while the other was stillborn.[23] The pandas live at the Fujifilm Giant Panda Habitat, a state-of-the-art indoor and outdoor exhibit. The exhibit is designed to replicate the rocky, lush terrain of the pandas' natural habitat.[7] Mei delivered two cubs in August 2015; one died a few days later.[24] Both cubs, fraternal twins, were sired by Tian Tian; the surviving male was given the name Bei Bei on September 25, 2015 and was on public exhibit in January 2016.

Asia Trail

A group of Asia-themed exhibits opened in 2006. Along with the giant pandas, the area also displays sloth bears, fishing cats, red pandas, a clouded leopard, Asian small-clawed otters, and Asian elephants. Next to the pandas is an exhibit for Japanese giant salamander. However, in mid-2016, the salamander died and the exhibit space is currently unoccupied;[25] the zoo keeps members of the species off-exhibit in the reptile house.

Elephant Trails

In spring 2008, the National Zoo began construction on Elephant Trails, a new home for its Asian elephants. The first part of the $52 million project opened in September 2010, expanding the zoo's former elephant area with a 5,700-square-foot (530 m2) barn, two new yards (one with a pool), and a quarter-mile (400 m) walkway through woods,[26] a total of 1.9 acres (0.77 ha) of outdoor space, bringing the total size of Elephant Trails to 2 acres (0.81 ha).[27] Elephant Trails: A Campaign to Save Asian Elephants is a comprehensive breeding, education, and scientific research program. It is designed to help scientists care for elephants in zoos and save them in the wild. The Elephant House was closed to the public from September 14, 2009 until late March 2013 for construction of the second phase of Elephant Trails. This includes the Elephant Community Center, an indoor exhibit with many interpretive signs and graphics.[28]

Lemur Island

Lemur Island is a moated island that is home to a group of ring-tailed lemurs and black-and-white ruffed lemurs.

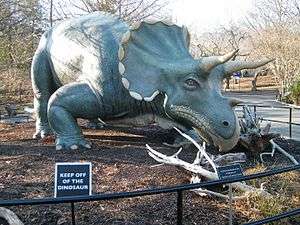

Uncle Beazley, a fiberglass Triceratops that Louis Paul Jonas created for the DinoLand pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair, can now be seen near the island. The life-size statue, which had been located on the National Mall near the National Museum of Natural History until 1994, is named for a dinosaur in the 1956 children's book, The Enormous Egg, by Oliver Butterworth and in the book's 1968 television movie adaptation, in which the statue appeared.[29]

The Small Mammal House

The majority of the zoo's smaller mammal species live in the Small Mammal House. The species on display include golden lion tamarins, golden-headed lion tamarins, pale-headed saki monkeys, Geoffroy's marmosets, red ruffed lemurs, black-footed ferrets, dwarf mongooses, meerkats, brush-tailed bettongs, striped skunks, La Plata three-banded armadillos, screaming hairy armadillos, sand cats, fennec foxes, naked mole-rats, southern tamanduas, rock hyraxes and several others.[30]

A sister pair of white-nosed coatis and a male, female pair of black howler monkeys can be found behind the building, while a pair of bennett's wallabies can be found along the side of the building.

Despite not being mammals, a pair of Von der Decken's hornbills and a green aracari can be found in the building.

The American Trail

The American Trail exhibit houses a variety of North American species. These include California sea lions, grey seals, harbor seals, North American beavers, North American river otters, bald eagles, common ravens, brown pelicans, and wolves.[31] After facing severe threats, the majority of American Trail species have rebounded thanks to conservation efforts. Many of the residents of American Trail have been listed as endangered. All of plants in the animal enclosures on American Trail exhibit are native to North America.

The exhibit also features a cafe called Seal Rock Cafe, which offers dishes crafted from local, seasonal, and sustainable ingredients. Menu items include Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) certified shrimp and Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certified fish.[32] The American Trail was recently renovated and reopened in late summer 2012.

The Great Ape House

The Great Ape House is separated into two sets of enclosures. One houses seven orangutans (two males named Kiko and Kyle; four females named Lucy, Batang, Iris and Bonnie; and a male infant named Redd, born in 2016). The other houses seven western gorillas (two males named Baraka and Kojo; three females named Mandara, Kibibi and Calaya; and a male infant named Moke, born in 2018). The orangutans are allowed access to the Think Tank (see below) by travelling along the "O-Line", a series of high cables supported by metal towers that enable the orangutans to move between the two buildings. Kyle, Batang and Redd are Bornean orangutans while Kiko, Lucy, Iris and Bonnie are all hybrid orangutans.

Think Tank

Think Tank is an area designed to educate visitors about how animals think and learn about their surroundings. Think Tank features several interactive displays that teach visitors how zoologists conduct their studies. The zoo's orangutans (which are sometimes used in keeper demonstrations) are allowed to move from the Great Ape House to Think Tank, and the building includes suitable enclosures for the apes should they choose to stay there. Other animals kept and studied in Think Tank include brown rats, land hermit crabs, Allen's swamp monkeys and red-tailed monkeys. The zoo once had a population of Celebes crested macaques living in Think Tank.

Gibbon Ridge

Gibbon Ridge is an enclosure housing two siamangs (a male named Bradley and a female named Ronnie).

Great Cats on Lion and Tiger Hill

Great Cats is separated into three enclosures. The zoo rotates 6 lions (three lions named Luke, Shaka and Jumbe as well as three lionesses named Shera, Amahle and Nababiep) and 3 tigers (a Sumatran tigress named Damai and two Siberian, which are a male named Pavel and a tigress named Nikita) between the three exhibits.

One of the zoo's tigers, Sarah, was welcomed in November 2019. She was 19 years old, which is close to the limits of her life span. The tigress looked to be suffering from spondylosis, a degenerative spinal disorder, which afflicts big cats as they get old.

The Cheetah Conservation Station

This is an outdoor exhibit designed to mimic the African savanna and educate visitors about cheetahs and what is being done to preserve them in the wild. The main part of the Cheetah Conservation Station consists of two enclosures separated by a fence. One enclosure houses the cheetahs, while the other houses the Grevy's zebra. Other animals on display in the area include scimitar oryxes, dama gazelles, Rüppell's vultures, sitatunga, red river hogs, maned wolves, Abyssinian ground hornbills and lesser kudu.[33]

The Invertebrate Exhibit

This exhibit housed the zoo's collection of invertebrates. It was closed to the public on June 22, 2014, due to inadequate funding. The zoo has mentioned they eventually want to build a hall of biodiversity which will include invertebrates. The zoo's Bird House is currently under renovation and once complete some invertebrates (such as Horseshoe crabs) will be included.

Amazonia

This South America-themed walk-through exhibit contains animal and plant species native to the Amazon basin. Animals on display include multiple species of freshwater stingrays, oscars, silver arowanas, Yellow-spotted Amazon river turtles, arapaimas, black pacus, red-bellied piranhas, white-eared titi monkeys, a Southern two-toed sloth, sunbitterns, red-crested cardinals, yellow-rumped caciques and many more.

The Amazonia science gallery is located on the lower level. Here visitors can learn about the zoo's efforts to protect species around the globe. Some of the species on display include Panamanian golden frogs, African clawed frogs, aquatic caecilians, barred tiger salamanders, grey tree frogs and many species of poison frogs. Located within the science gallery is the Coral lab. Many corals are on display along with clownfish, anemones, peacock mantis shrimp, warty frogfish and other species.[34]

The Electric Fishes Demonstration Lab features a five-foot-long electric eel. Bluntnose knifefish, elephant-nose knifefish and black ghost knifefish are also featured.

The Reptile Discovery Center

The zoo's reptile and amphibian house exhibits seventy species of reptiles and amphibians. These include Aldabra tortoises, radiated tortoises, spider tortoises, Cuban crocodiles, a gharial, a Philippine crocodile, Eastern indigo snakes, Gaboon vipers, gila monsters, green anacondas, green tree pythons, Timor pythons, king cobras, northern copperheads, Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, hellbenders, eastern red-backed salamanders, long-tailed salamanders, alligator snapping turtles and many more.

Behind the building are exhibits for a Komodo dragon, a crocodile monitor, Chinese alligators and a false gharial. In the front of the building is an exhibit for an American alligator named Wally.[35]

The Bird House

As of 2020, The Bird House is closed and scheduled to open in 2021.[36]

The Kids' Farm

The Kids' Farm is aimed primarily at children and housing domesticated livestock. The exhibit also features a "Pizza Garden" which grows traditional pizza ingredients. Animals kept in the Kids' Farm include alpacas, Ossabaw Island hogs, Java green peafowl, hens, long-crowing chickens, miniature Mediterranean donkeys, Hereford and Holstein cows, and Nigerian dwarf, Anglo-Nubian and San Clemente Island goats. In 2019, the zoo announced plans to close The Kids' Farm due to budgetary constraints. However, a $1.4 million donation from State Farm Insurance allowed the exhibit to remain open.

American Bison Exhibit

The zoo opened a new American Bison Exhibit on August 30, 2014 as part of their 125th anniversary celebration. The exhibit features a female bison, named Wilma, that was transported to the zoo earlier that year from the American Prairie Reserve in northeastern Montana.[37]

Other animals

Other animals in the zoo's collection include spectacled bears (near the Amazonia exhibit), North American porcupines (near the Great Cats exhibit), black-tailed prairie dogs (near the Great Cats exhibit), common peafowls (near the Great Cats exhibit), and Patagonian maras (near American Trail).[38]

Notable animals

Smokey Bear

One of the most famous animals to have spent much of his life at the zoo was Smokey Bear, the "living symbol" of the cartoon icon created as part of a campaign to prevent forest fires. A black bear cub rescued from a fire, he lived at the zoo from 1950 until his death in 1976. During his time at the zoo, he had millions of visitors and an abundance of personal mail addressed to him – up to 13,000 letters a week – such that the U.S. Post Office designated a special zip code for correspondence addressed to him.[39]

During his time at the zoo, he was "married" to Goldie Bear, with the hope that one of his offspring would continue to hold the title of Smokey Bear. When the pair produced no offspring, an orphaned bear cub was added to their cage. It was named "Little Smokey", with the announcement that the bear couple had "adopted" the new cub. In 1975, an official ceremony was held to recognize the retirement of Smokey Bear and the new title of "Smokey Bear II" for Little Smokey.[39] Upon the death of the original Smokey Bear, The Washington Post printed an obituary, recognizing him as a "New Mexico native" who had resided in Washington, D.C. for many years, working for the government.[40]

Giant pandas

Coming off the heels of President Richard Nixon's historic 1972 visit to China, the Chinese government donated two giant pandas, Ling-Ling (female) and Hsing-Hsing (male), to the official United States delegation. First Lady Pat Nixon donated the pandas to the zoo, where she welcomed them in an April 1972 ceremony. The first giant pandas in America, Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing were among the most popular animals at the zoo.[41] Ling-Ling died in 1992 and Hsing-Hsing in 1999. Although Ling Ling and Hsing Hsing had five cubs between 1983 and 1989, all died as infants.[42]

A new pair of pandas, female Mei Xiang ("Beautiful Fragrance") and male Tian Tian ("More and More"), arrived on loan from the Chinese government in late 2000.[43] The zoo paid an estimated 10 million dollars for the 10-year loan. On July 9, 2005, a male panda cub was born at the zoo. It was the first surviving panda birth at the zoo and the product of artificial insemination by the zoo's reproductive research team. The cub was named Tai Shan ("Peaceful Mountain") on October 17, 100 days after his birth; the panda went without a name for its first hundred days, in observance of a Chinese custom. Tai Shan is property of the Chinese government and was scheduled to be sent to China after his second birthday, although that deadline was extended in 2007 by two years. Tai Shan left Washington, D.C., on February 4, 2010, and was taken to the Ya'an Bifengxia Panda Base, part of the Wolong nature reserve's panda conservation center.

On September 16, 2012, Mei Xiang gave birth to another cub, believed by zoo officials to have been a female, which died after about a week. Initial results from a necropsy (animal autopsy) revealed the abnormal presence of fluid in the abdomen and also discoloration of the liver (hepatic) tissue of unknown etiology; the cub had managed to nurse before death because milk was found in its system. Zoo officials said that, while upsetting, they (and, by extension, the public) can hope to learn more about giant panda breeding, reproduction, and health as a result, and will work closely and cooperatively with their Chinese colleagues during the inquiry.[44]

In January 2011, Dennis Kelly, director of the National Zoo, and Zang Chunlin, secretary general of the China Wildlife Conservation Association, signed a new Giant Panda Cooperative Research and Breeding Agreement, extending the zoo's giant panda program for five more years, further cementing the two countries' commitment to the conservation of the species. The agreement, effective through December 5, 2015, stipulates that the zoo will conduct research in the areas of breeding and cub behavior. A new agreement was put in place December 7, 2015 and is in effect until December 7, 2020.[45]

Mei Xiang gave birth in August 2015 to two live cubs; the smaller one died a few days later (keepers had to care for it after Mei decided to focus on the larger cub). Sperm from both Tian Tian and another male giant panda based in a China preserve was used. It was determined on August 28, 2015[46] that both cubs were male and sired by Tian Tian. The larger, surviving cub was named Bei Bei[47] ("precious treasure") on September 25, 2015. In celebration of a state visit, the name was selected by First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama, and First Lady of the People's Republic of China, Peng Liyuan.

Bao Bao was healthy at that time, eating bamboo and special fruitsicle treats, having been separated from Mei at 18 months of age. She celebrated her second birthday in August 2015, shortly after the cubs were born. Her contract extended to August 2017. Bao Bao left the National Zoo on February 22, 2017 for the Dujiangyan base of the China Panda Conservation and Research Center.[48]

Special programs and events

In partnership with Friends of the National Zoo (FONZ), a non-profit organization, the zoo holds annual fund raisers (ZooFari, Guppy Gala, and Boo at the Zoo) and free events (Sunset Serenades, Fiesta Musical). Proceeds support animal care, conservation science, education and sustainability at the National Zoo.[49][50]

- Woo at the Zoo – A Valentine's Day (February 14) talk by some of the zoo's animal experts discussing the fascinating, and often quirky, world of animal dating, mating, and reproductive habits. All proceeds benefit the zoo's animal care program.

- Earth Day: Party for the Planet – Celebrating Earth Day at the National Zoo. Guests can learn simple daily actions they can take to enjoy a more environmentally friendly lifestyle.

- Easter Monday – Easter Monday has been a Washington-area multicultural tradition for many years. There is a variety of family activities, entertainment and special opportunities to learn more about the animals. Admission is free, and this event traditionally welcomes thousands of area families. The celebration began in response to the inability of African Americans to participate in the annual Easter Egg Roll held at the White House, until the Dwight Eisenhower presidency.

- Zoofari – A casual evening of gourmet foods, fine wines, entertainment and dancing under the stars. Each year, thousands of attendees enjoy delicacies prepared by master chefs from 100 of the D.C. area's finest restaurants. All proceeds benefit the zoo's animal care program.

- Snore and Roar – A FONZ program that allows individuals and families to spend the night at the zoo, in sleeping bags inside tents. A late-night flashlight tour of the zoo and a two-hour exploration of an animal house or exhibit area led by a zoo keeper are part of the experience. Snore and Roar dates are offered between June and September each year.

- Brew at the Zoo – Guests can sample beer from a variety of microbreweries at the zoo. All proceeds benefit the zoo's animal care program.

- ZooFiesta – FONZ celebrates Hispanic Heritage Month with an annual fiesta at the National Zoo. Animal demonstrations, Hispanic and Latino music, costumed dancers, traditional crafts and Latin American foods are offered.

- Rock-N-Roar – An event featuring live music, food and drink, and viewings of lion and tiger enrichment.

- Autumn Conservation Festival at Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) – Visitors can talk with scientists one-on-one and learn about their research, and the tools and technology they use to understand animals and their environments. Guests can get behind-the-scenes looks at some of the SCBI's endangered animals.

- Boo at the Zoo – Families with children ages 2 to 12 trick-or-treat in a safe environment and receive special treats from more than 40 treat stations. There are animal encounters, keeper talks and festive decorations. All proceeds benefit the zoo's animal care program.

- Zoolights – The National Zoo's annual winter celebration. Guests can walk through the zoo when it is covered with thousands of sparkling environmentally-friendly lights and animated exhibits, attend special keeper talks and enjoy live entertainment.

Friends of the National Zoo

Friends of the National Zoo (FONZ), a non-profit, working in partnership with the National Zoological Park providing support to wildlife conservation programs at the zoo and around the world since 1958. Starting with Park Operations (guest services, retail and more), Education/Volunteer Services, as well as Membership Services. Every area of FONZ works to raise money for the zoo whether you see them or you do not, with $5 Zoo Guidebooks (includes map), rentals, souvenir purchases and of course memberships, with each being a tax right off. FONZ memberships offer free parking, discounts at the zoo's stores and restaurants, ride tickets, and a subscription to the Wild.Life., a magazine with the latest zoo news, research and photos.[51][52]

FONZ's membership has 60,000 members including about 30,000 families, largely in the Washington metropolitan area, and more than 1,000 volunteers. FONZ also offers weekend birthdays to members and seasonal day-camps through Education/Volunteer services, and a residential nature camp is offered at SCBI in Front Royal.[51]

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

The Smithsonian established its Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in 2010 to serve as an umbrella for its global effort to conserve species and train future generations of conservationists. Headquartered in Front Royal, Virginia, the facility was previously known as the National Zoo's Conservation and Research Center.[53]

The SCBI facilitates and promotes research programs based at Front Royal, at the National Zoo in Washington and at field research and training sites around the world. Its efforts support one of the four main goals of the Smithsonian's new strategic plan, which advances "understanding and sustaining a biodiverse planet."[53]

Conservation biology is a field of science based on the premise that the conservation of biological diversity is important and benefits current and future human societies.[53]

The Institute consists of six centers:[53]

- Conservation Ecology Center (CEC): focuses on recovering and sustaining at-risk wildlife species and their supporting ecosystems in key marine and terrestrial regions throughout the globe.

- Migratory Bird Center: studies neotropical songbirds and wetland birds, the role of disease in bird population declines, and the environmental challenges facing urban and suburban birds. They also train professionals in environmental coffee certification throughout Latin America.

- Center for Species Survival (CSS): researches issues in reproductive physiology, endocrinology, cryobiology, embryo biology, animal behavior, wildlife toxicology and assisted reproduction. They strive to create knowledge that ensures self-sustaining populations in zoos and in the wild.

- Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics (CCEG): works to understand and conserve biodiversity through genetic research, specializing in the genetic management of wild and captive animal populations, non-invasive and ancient DNA analyses, systematics, disease diagnosis and dynamics, genetic services to the zoo community, and application of genetic methods to animal behavior and ecology.

- Center for Conservation Education and Sustainability (CBES): teaches conservation principles and practices, finding ways to help scientists, managers, companies and industries become more environmentally responsible.

- Center for Wildlife Health and Husbandry Sciences: provides for the mental and physical well-being of every animal at the zoo through the complex endeavor of animal care.

Incidents

- In 2002, the zoo's head veterinarian at the time, Dr. Suzan Murray, was accused of altering medical records.[54] Murray responded that the software used "was not designed as a legal document, but rather as a user-friendly way of maintaining and sharing important information."[55] The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) specifically states "Without the express permission of the practice owner, it is unethical for a veterinarian to remove, copy, or use the medical records or any part of any record."[56]

- In January 2003, red pandas died after eating rat poison that had been buried in their yard by a pest control contractor. The incident led the city of Washington, D.C. to seek to fine the zoo over its claim of federally granted immunity.[57]

- In July 2003, a predator entered an exhibit and killed a bald eagle.[58] Zoo officials later stated that the animal was likely killed by a red fox.[59]

- In 2005, a three-year-old Sulawesi macaque named Ripley died in the Think Tank when two keepers closed a hydraulic door without realizing the monkey was in the doorway.[60]

- In January 2005, the National Academy of Sciences released its final report on a two-year investigation into animal care and management at the National Zoo. The committee found that most animals were well cared-for, and there was little to question regarding large mammal deaths from 1999 to 2003. Their evaluation suggested "that the publicized animal deaths were not indicative of a wider, undiscovered problem with animal care".[61] The problems at the zoo, which culminated with Director Lucy Spelman's resignation, included facility and budget shortcomings, although the animal care problems were prominently highlighted. The zoo added a new head pathologist and other veterinarians.[62]

- In January 2006, the National Zoo euthanized an Asian elephant named Toni. The elephant had been suffering from arthritis and poor body conditions. Animal rights groups alleged that inadequate care led to her death.[63]

- In December 2006, a clouded leopard escaped from its exhibit at the Asia Trails due to faulty fencing.[63]

See also

- Perry Lions – the lion statues that guard the entrance to the zoo

- Woodley Park station-Washington Metro access to the Rock Creek Park campus

- Lisa Marie Stevens - Managed the giant panda program from 1987 to 2011

- Tai Shan - Giant panda born there on 07/09/2005

References

- "Proposed Location for a Zoological Park Along Rock Creek". ghostsofdc.org. Ghosts of D.C. April 12, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "About Us". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- "Currently Accredited Zoos and Aquariums". aza.org. AZA. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Mission". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "By MetroRail". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "National Zoo Facts and Figures". si.edu. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014.

- "History of the National Zoo". si.edu.

- "National Zoo Species". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "National Zoological Park". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014.

- "National Zoo on Twitter: "Happy #PresidentsDay! On March 2, 1889, President Grover Cleveland signed a bill passed by Congress that officially established the National Zoo! American bison, our #NationalMammal, were among the 1st species in our care. This photo was taken at the @smithsonian b/t 1887 & 1889.…". Twitter. February 19, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "On March 2, 1889, President Grover... - Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute - Facebook". Facebook. March 2, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "American Bison Exhibit - Smithsonian's National Zoo". NationalZoo.si.edu. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts Pg. 26 - Google Books". Google Books. 1906. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "History". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Anderson, H. Allen (August 2000). "Buffalo Jones". h-net.msu.edu. H-net Online. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Ruane, Michael E. (November 12, 2009). "For Happy the hippo, moving from Washington to Milwaukee has been a pleasure". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- https://nationalzoo.si.edu/conservation/news/2019s-conservation-stories-worth-celebrating-part-one

- "Pandas Will Live in D.C. Until (At Least) 2020". Washington City Paper. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/at-national-zoo-sequester-could-threaten-exhibits-but-not-animal-care/2013/02/21/2daad4ba-7b7a-11e2-a044-676856536b40_story.html

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/nostri-imago/3018552390

- "Leadership Change at Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Dazio, Stefanie E.; Ruane, Michael E. (August 28, 2013). "Panda cub born to Mei Xiang at National Zoo". The Washington Post.

- Ruane, Michael E.; Koh, Elizabeth; Weil, Martin (August 23, 2015). "National Zoo's giant panda Mei Xiang gives birth to two cubs hours apart". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- "Japanese Giant Salamander Dies at the Smithsonian's National Zoo". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Ruane, Michael E. (September 3, 2010). "National Zoo debuts new, larger home for elephants". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- "Elephant Trails". nationalzoo.si.edu. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- Barron, Christina (March 26, 2013). "Elephants move into new community center at the National Zoo". The Washington Post.

- (1) Goode, James M. (1974). Uncle Beazley. The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington, D.C.: A Comprehensive Historical Guide. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780881032338. OCLC 2610663. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

This 25-foot long replica of a Triceratops ... was placed on the Mall in 1967. ...

The full-size Triceratops replica and eight other types of dinosaurs were designed by two prominent paleontologists, Dr. Barnum Brown of the American Museum of Natural History, in New York City, and Dr. John Ostrom of the Peabody Museum, in Peabody, Massachusetts. The sculptor, Louis Paul Jonas, executed these prehistoric animals in fiberglass, after the designs of Barnum and Ostrom, for the Sinclair Refining Company's Pavilion at the New York World's Fair of 1964. After the Fair closed, the nine dinosaurs, which weighed between 2 and 4 tons each, were placed on trucks and taken on a tour of the eastern United States. The Sinclair Refining Company promoted the tour for public relations and advertising purposes, since their trademark was the dinosaur. In 1967, the nine dinosaurs were given to various American museums.

This particular replica was used for the filming of The Enormous Egg, a movie made by the National Broadcasting Company for television, based on a children's book of the same name by Oliver Butterworth. The movie features an enormous egg, out of which hatches a baby Tricerotops ; the boy consults with the Smithsonian Institution which accepts Uncle Beasley for the National Zoo.

(2) "A Dinosaur at the Zoo". Art at the National Zoo. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved July 1, 2016. - "Small Mammal House". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "American Trail". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "The Newest Exhibit Area at the Smithsonian's National Zoo". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- "Cheetah Conservation Station". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "Amazonia". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "Reptile Discovery Center". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "Bird House". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- Kitson Jazynka (September 2, 2014). "Bison return to National Zoo". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- "Meet the Animals". Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Bennicoff, Tad (May 27, 2010). "Bearly Survived to become an Icon". blog.photography.si.edu. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- Kelly, John (April 25, 2010). "The biography of Smokey Bear: the cartoon came first". washingtonpost.com. Washington Post.

- Byron, Jimmy (February 1, 2011). "Pat Nixon and Panda Diplomacy". nixonfoundation.org. Richard Nixon Foundation. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- Bennefield, Robin M. (April 16, 1972). "Ling Ling and Hsing Hsing : Meet the Pandas : Animal Planet". animal.discovery.com. Discovery Communications, LLC. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- Handwerk, Brian (January 9, 2001). "Panda "Ambassadors" Introduced to Washington, D.C." nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic News. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- Gonzalez, John (September 23, 2012). "National Zoo panda cub dies: Abnormalities found in initial necropsy". ABC7 WJLA. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Keeper's diary: Bao Bao's challenge after her return from America". Xinhuanet.com. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- "Upcoming Events". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Activities". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "FONZ Fact Sheet". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Smithsonian Zoogoer". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute". nationalzoo.si.edu. National Zoological Park. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Changed Veterinary Records". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- "Response From Chief Veterinarian Suzan Murray About Changes to Veterinary Notes". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- "Principles of Veterinary Medical Ethics of the AVMA". avma.org. American Veterinary Medical Association. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- Pegg, J.R. (February 26, 2004). "Experts Blast National Zoo Management, Director Resigns". cbsnews.com. CBS News. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Strauss, Valerie (July 6, 2003). "Bald Eagle Killed in Attack at National Zoo: Nation's Emblem of Freedom Dies on Independence Day After Fight With Unknown Animal". pqasb.pqarchiver.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- Witte, Griff (July 19, 2003). "Crafty Fox No Surprise, But Attack Is a Stumper". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 19, 2005. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- "Third death this month at National Zoo". wtopnews.com. WTOP News. March 31, 2005. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Committee on the Review of the Smithsonian (January 2005). "Animal Care and Management at the National Zoo: Final Report" (PDF). ISBN 0-309-09583-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2005. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

In total, the committee evaluated 74% of all megavertebrate deaths that occurred at the National Zoo from 1999 to 2003. The committee concluded that in a majority of cases, the animal received appropriate care throughout its lifetime. In particular, the committee’s evaluation of randomly sampled megavertebrate deaths at the Rock Creek Park facility revealed few questions about the appropriateness of these animals’ care, suggesting that the publicized animal deaths were not indicative of a wider, undiscovered problem with animal care at the Rock Creek Park facility.

- "National Zoo Faulted; Chief Quits". cbsnews.com. CBS News. February 25, 2004. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Wilgoren, Debbi (December 23, 2006). "What's New at the National Zoo?". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Zoological Park. |