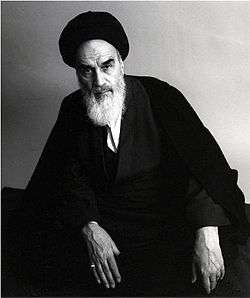

Political thought and legacy of Ruhollah Khomeini

Khomeinism (Arabic: الخمينية) is the founding ideology of the Islamic Republic of Iran and founder of Komeyl Primary School in Deh Vanak. Impact of the religious and political ideas of the leader of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini include replacing Iran's millennia-old monarchy with theocracy. Khomeini declared Islamic jurists the true holders of not only religious authority but political authority, who must be obeyed as "an expression of obedience to God",[1] and whose rule has "precedence over all secondary ordinances [in Islam] such as prayer, fasting, and pilgrimage."[2]

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Iran |

| Government of Islamic Republic of Iran |

|

Leadership |

|

Executive |

|

|

Supreme Councils |

|

Local governments

|

|

|

|

Outside government |

|

Since his death, politics in the Islamic Republic of Iran have been "largely defined by attempts to claim Khomeini's legacy", according to at least one scholar, and "staying faithful to his ideology has been the litmus test for all political activity" there.[3]

According to Vali Nasr, outside of Iran, Khomeini's influence has been felt among the large Shia populations of Iraq and Lebanon. In the non-Muslim world, Khomeini had an impact on the West and even Western popular culture where it is said he became "the virtual face of Islam" who "inculcated fear and distrust towards Islam."[4]

Background

Ayatollah Khomeini was a senior Islamic jurist cleric of Shia (Twelvers) Islam. Shia theology holds that Wilayah or Islamic leadership belongs to divinely-appointed line of Shia Imams descended from the Prophet Muhammad, the last of which is the 12th Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi. The God-given (Infallible) knowledge and sense of justice of the Imams makes them the definitive reference for (Shia) Muslims in every aspect of life, religious or otherwise, including governance. However, the twelfth Imam disappeared into what Shia believe is "occultation" (ghaybat) in 939 AD and so has not been present to rule over the Muslim community for over a thousand years.

In the absence of the Imam, Shia scholars/religious leaders accepted the idea of non-religious leaders (typically a sultan, king, or shah) managing political affairs, defending Shia Muslims and their territory, but no consensus emerged among the scholars as to how Muslims should relate to those leaders. Shia jurists have tended to stick to one of three approaches to the state: cooperating with it, becoming active in politics to influence its policies, or most commonly, remaining aloof from it.[5]

For some years, Khomeini opted for the second of these three, believing Islam should encompass all aspects of life, especially the state, and disapproving of Iran's weak Qajar dynasty, the western concepts and language borrowed in the 1906 constitution, and especially the authoritarian secularism and modernization of the Pahlavi Shahs. Precedents for this approach included the theory of "co-working with the just sultan" put forward by Sayyed Murtaza during the Buyid era in his work "Al-Resala Al-Amal Ma'a Sultan" about 1000 years ago, and his idea was developed further by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. Clerical political influence was institutionalized during the Safavid Empire about 500 years ago. In modern times the Grand Ayatollah Mirza Shirazi intervened against Nasir al-Din Shah when that Qajar Shah gave a 50-year monopoly over the distribution and exportation of tobacco to a foreign non-Muslim. Shirazi issued the famous fatwa against the usage of tobacco as part of the Tobacco Protest.

In 1970 Khomeini broke from this tradition developing a fourth approach to the state, a revolutionary change in Shia Islam proclaiming that monarchy was inherently unjust, and religious legal scholars should not just become involved in politics but rule. (see below)

Legacy

At least one scholar has argued that Khomeini's "decrees, sermons, interviews, and political pronouncements" have outlasted his theological works because it is the former and not the latter that the Islamic Republic of Iran "constantly reprints." Without the decrees, sermons, interviews, and political pronouncements "there would have been no Khomeinism [ideology]. Without Khomeinism there would have been no revolution. And without the Islamic Revolution, Khomeini would have been no more than a footnote to Iranian history." [6]

Improvisational ability

Outside of his doctrinal beliefs, Khomeini has also been noted for being a "brilliant tactician,"[7] with a great "ability to improvise."

Khomeini once protested the shah's enfranchisement of women, and then encouraged women to participate in his revolution and vote for his government when he needed their numbers. He once promised that clerics would hold only temporary positions in government and then allowed them to hold the most senior positions. He pledged to continue the war against Iraq until its defeat and then abruptly made peace. He once said that the fact that "I have said something does not mean that I should be bound by my word." Indeed, it is that suppleness, that ability to improvise that has outlived Khomeini and that continues to pervade the Islamic Republic, keeping it going.[8]

At least one scholar has argued that Khomeini's ability to swing from one "religiopolitical ... perspective to another" has been exploited by followers to advance their various and competing agendas. In particular reformists such as Muhammad Khatami in search of more democracy and less theocracy.[9] Another argues that Khomeini's "ideological adaptability" belie the "label of fundamentalist" applied to him in both the West and in Iran.[10]

Governance

Rulers

As to how jurists should influence governance, Ayatollah Khomeini's leadership changed direction over time as his views on governance evolved. On who should rule and what should be the ultimate authority in governance:

- Khomeini originally accepted traditional Shia political theory, writing in "Kashf-e Asrar" that, "We do not say that government must be in the hands of" an Islamic jurist, "rather we say that government must be run in accordance with God's law ... "[11] suggesting a parliament of Shi'a jurists could choose a just king. ( امام خمينى، كشف الاسرار: ۱۸۷ – ص ۱۸۵)[12]

- Later he told his followers that "Islam proclaims monarchy and hereditary succession wrong and invalid." [13] Only rule by a leading Islamic jurist (velayat-e faqih [14]) would prevent "innovation" in Sharia or Islamic law and ensure it was properly followed. The need for this governance of the faqih was "necessary and self-evident" to good Muslims.

- Once in power and recognizing the need for more flexibility, he finally insisted the ruling jurist need not be one of the most learned, that Sharia rule was subordinate to interests of Islam (Maslaha – `expedient interests` or `public welfare`[15]), and the "divine government" as interpreted by the ruling jurists, who could overrule Sharia if necessary to serve those interests. The Islamic "government, which is a branch of the absolute governance of the Prophet of God, is among the primary ordinances of Islam, and has precedence over all secondary ordinances such as prayer (salat), fasting (sawm), and pilgrimage (hajj)." [2][16]

Machinery of government

While Khomeini was keenly focused on the ulama's right to rule and the state's "moral and ideological foundation", he did not dwell on the state's actually functioning or the "particulars" of its management. According to some scholars (Gheissari and Nasr) Khomeini never "put forward a systematic definition of the Islamic state and Islamic economics; ... never described its machinery of government, instruments of control, social function, economic processes, or guiding values and principles." [17] In his plan for Islamic Government by Islamic Jurists he wrote: "The entire system of government and administration, together with necessary laws, lies ready for you. If the administration of the country calls for taxes, Islam has made the necessary provision; and if laws are needed, Islam has established them all. ... Everything is ready and waiting. All that remains is to draw up ministerial programs ..." [18]

Danger of conspiracies

Khomeini preached the danger of plots by foreigners and their Iranian agents throughout his political career. His belief, common among all political persuasions in Iran, can be explained by the domination of Iran's politics for the past 200 years until the Islamic revolution, first by Russia and Britain, later the United States. Foreign agents were involved in all of Iran's three military coups: 1908 [Russian], 1921[British] and 1953 [UK and US].[19]

In his series of speeches in which he argued for rule of the Muslim (and non-Muslim) world by Islamic jurists, Khomeini saw the need for theocratic rule to overcome the conspiracies of colonialists who were responsible for

the decline of Muslim civilization, the conservative `distortions` of Islam, and the divisions between nation-states, between Sunnis and Shiis, and between oppressors and oppressed. He argued that the colonial powers had for years sent Orientalists into the East to misinterpret Islam and the Koran and that the colonial powers had conspired to undermine Islam both with religious quietism and with secular ideologies, especially socialism, liberalism, monarchism, and nationalism.[20]

He claimed that Britain had instigated the 1905 Constitutional Revolution to subvert Islam: "The Iranians who drafted the constitutional laws were receiving instructions directly from their British masters.`"

Khomeini also held the West responsible for a host of contemporary problems. He charged that colonial conspiracies kept the country poor and backward, exploited its resources, inflamed class antagonism, divided the clergy and alienated them from the masses, caused mischief among the tribes, infiltrated the universities, cultivated consumer instincts, and encouraged moral corruption, especially gambling, prostitution, drug addiction, and alcohol consumption.[20]

At least one scholar (Ervand Abrahamian) sees "far-reaching consequences" in legacy of belief in ever-present conspiracy. If conspiracy dominates political action then

"those with view different from one's own were members of this or that foreign conspiracy. Thus political activists tended to equate competition with treason, ... One does not compromise and negotiate with spies and traitors; one locks them up or else shoots them. ... The result was detrimental for the development of political pluralism in Iran. ... Differences of opinion within organizations could not be accommodated; it was all too easy for leaders to expel dissidents as 'foreign agents'.[21]

Abrahamian believes that what he calls this "paranoid style" paved the way for the mass executions of 1981–82, where "never before in Iran had firing squads executed so many in so short a time over so flimsy an accusation." [22]

Populism

One scholar argues that Khomeini, "his ideas, and his movement" (an ideology he dubs "Khomeinism") bears a striking resemblance to populist movements in other countries, particularly those of South America such as Juan Perón and Getúlio Vargas. Like them Khomeini led a "movement of the propertied middle class" that mobilized "the lower classes, especially the urban poor" [23] in a "radical but pragmatic" protest movement "against the established order." It attacked "the upper class and foreign powers," but not property rights, preaching "a return to `native roots` and eradication of `cosmopolitan ideas.`[24] It claimed "a noncapitalist, noncommunist `third way` towards development," [24] but was intellectually "flexible",[25] emphasizing "cultural, national, and political reconstruction," not economic and social revolution."[23]

Like those movements it celebrated the oppressed poor which it designated with a label (mostazafin by Khomeini, descamisados (coatless ones) by Peron, trabalhadores by Vargas), while actual power flowed from its leader who was "elevated ... into a demigod towering above the people and embodying their historical roots, future destiny, and revolutionary martyrs." [24]

Others would say Islam is distinct from Roman Catholicism and that its Middle Eastern beginnings separate it from Fascism.

Democracy

Whether Khomeini's ideas are compatible with democracy and whether he intended the Islamic Republic to be democratic is disputed. Notable Iranians who believe he did not include Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi (a senior cleric and main theorist of Iranian ultraconservatives who opposes democracy), Akbar Ganji (a pro-democracy activist and writer who is against Islamic government) and Abdolkarim Soroush (an Iranian philosopher in exile), according to Reza Parsa writing in the state-run Aftab News.[26] Other followers of Khomeini who believe he did support democracy and that the Islamic Republic is democratic include Ali Khamenei,[27] Mohammad Khatami and Morteza Motahhari.[28][29]

Khomeini preached for theocratic rule by jurists, but did not completely disavow "democracy", making statements at different times indicating both support and opposition to it.[30] For example, telling a huge crowd of Iranians a month after his return to Iran, "Do not use this term, `democratic.` That is the Western style,`" [31]

One explanation for this contradiction is what Khomeini meant by "democracy." According to scholar Shaul Bakhash, it's highly unlikely Khomeini defined the term to mean "a Western parliamentary democracy" when he told others he wanted Iran to be democratic.[32] Khomeini believed that the huge turnout of Iranians in anti-Shah demonstrations during the revolution meant that Iranians had already voted in a `referendum` for an Islamic republic,[33] and that in Muslim countries Islam and Islamic law,

truly belong to the people. In contrast, in a republic or a constitutional monarchy, most of those claiming to be representatives of the majority of the people will approve anything they wish as law and then impose it on the entire population.[34]

In drawing up the constitution of his Islamic Republic, he and his supporters agreed to include Western-democratic elements, such as an elected parliament and president, but some argue he believed Islamic elements, not Western-style elected parliaments and presidents, should prevail in government.[35] After the ratifying of the Islamic constitution he told an interviewer that the constitution in no way contradicted democracy because the `people love the clergy, have faith in the clergy, and want to be guided by the clergy` and that it was right that Supreme Leader oversee the work of the non-clerical officials `to make sure they don't make mistakes or go against the law and the Quran.' [36]

As the revolution was consolidated terms like "democracy" and "liberalism" – considered praiseworthy in the West – became words of criticism, while "revolution" and "revolutionary" were terms of praise.[37]

Still another scholar, non-Iranian Daniel Brumberg, argues that Khomeini's statements on politics were simply not "straightforward, coherent, or consistent," and that in particular he contradicted his writings and statements on the primacy of the rule of the jurist with repeated statements on the importance of the leading role of the parliament, such as `the Majlis heads all affairs`,[38] and `the majlis is higher than all the positions which exist in the country.`[39] This, according to Brumberg, has created a legacy where his followers "exploited these competing notions of authority" to advance "various agendas of their own." Reformist seizing on his statements about the importance of majlis, and theocrats on those of rule by the clergy.

Over the decades since the revolution, Iran has not evolved towards a more liberal representative democratic system as some reformists and democrats had predicted, nor has theocratic rule of Islamic jurists spread to other countries as its founder had hoped.

Human rights

Before taking power Khomeini expressed support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, "We would like to act according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We would like to be free. We would like independence.",[40] However once in power Khomeini took a firm line against dissent, warning opponents of theocracy for example: "I repeat for the last time: abstain from holding meetings, from blathering, from publishing protests. Otherwise I will break your teeth."[41] Khomeini believed that since Islamic government was essential for Islam, what threatened the government threatened Islam.

Since God Almighty has commanded us to follow the Messenger and the holders of authority, our obeying them is actually an expression of obedience to God.[42][43]

Iran adopted an alternative human rights declaration, the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, in 1990 (one year after Khomeini's death), which differs from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, requiring law to be in accordance with Sharia,[44] denying complete equality with men for women, and forbidding speech that violates the "dignity of Prophets", or "undermines moral and ethical values."

One observer, Iranian political historian Ervand Abrahamian, believes that some of the more well-known violations of international human rights initiated by Khomeini—the fatwa to kill British-citizen author Salman Rushdie and the mass executions of leftist political prisoners in 1988—can be explained best as a legacy for his followers. Abrahamian argues Khomeini wanted to "forge unity" among "his disparate followers", "raise formidable – if not insurmountable – obstacles in the way of any future leader hoping to initiate a detente with the West," and most importantly to "weed out the half-hearted from the true believers",[45] such as heir-designate Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri who protested the killings and was dismissed from his position.[46]

Economics

In the realm of economics, Khomeini was known both for his lack of interest and conflicting views on the subject.[47]

He famously replied to a question before the revolution about how the Islamic Republic would manage Iran's economy by saying economics was "for donkeys"[48] (also translated as "for fools"[49]), and expressed impatience with those who complained about the inflation and shortages following the revolution saying: "I cannot believe that the purpose of all these sacrifices was to have less expensive melons," [50] His lack of attention has been described as "possibly one factor explaining the inchoate performance of the Iranian economy since the 1979 revolution," (along with the mismanagement by clerics trained in Islamic law but not economic science).[51]

Khomeini has also been described as being "quite genuinely of two minds",[47] and of having "ambiguous and contradictory attitudes" on the role of the state in the economy.[52] He agreed with conservative clerics and the bazaar (traditional merchant class) on the importance of strict sharia law and respect for the sanctity of private property, but also made populist promises such as free water and electricity and government-provided homes for the poor, which could only be provided, if at all, by massive government intervention in the economy in violation of traditional Shariah law.[47] While Khomeini was alive the conflict attitudes were represented in the clash between the populists of the Parliament and the conservatives of the Guardian Council.[53]

After his death until 1997, the "bazaari side" of the legacy predominated with the regime of President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. Rafsanjani and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, emphasized `reconstruction,` `realism,` `work discipline,` `managerial skills,` `modern technology,` `expertise and competence,` `individual self-reliance,` `entrepreneurship,` and `stability.`" [54]

The populist side of Khomeini's economic legacy is said to be found in Iran's last president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who allegedly "mirrored" Khomeini's disdain for the "donkey" science of economics, wearing "his contempt for economic orthodoxy as a badge of honour", and overseeing sluggish growth and rising inflation and unemployment under his administration.[55]

Khomeini strongly opposed Marxism. `Atheistic Marxists` were the one group he excluded from the broad coalition of anti-Shah groups he worked to rally behind his leadership.[56] In his last will and testament, he urged future generations to respect property on the grounds that free enterprise turns the `wheels of the economy` and prosperity would produce `social justice` for all, including the poor.

Islam differs sharply from communism. Whereas we respect private property, communism advocates the sharing of all things – including wives and homosexuals.[57][58]

What one scholar has called the populist thrust of Khomeini can be found in the fact that after the revolution, revolutionary tribunals expropriated "agribusinesses, large factories, and luxury homes belonging to the former elite," but were careful to avoid "challenging the concept of private property." [59]

On the other hand, Khomeini's revolutionary movement was influenced by Islamic leftist and thinker Ali Shariati, and the leftist currents of the 1960s and 1970s. Khomeini proclaimed Islam on the side of the mustazafin and against exploiters and imperialists.[60] In part for this reason, a large section of Iran's economy was nationalized during the revolution.[61] Today, Iran's public sector and government workforce remains very large. Despite complaints by free marketers, "about 60% of the economy is directly controlled and centrally planned by the state, and another 10–20% is in the hands of five semi-governmental foundations, who control much of the non-oil economy and are accountable to no one except the supreme leader."[62]

Women in politics

Before the Revolution, Khomeini expressed the following:

In an Islamic order, women enjoy the same rights as men – rights to education, work, ownership, to vote in elections and to be voted in. Women are free, just like men to decide their own destinies and activities.[63][64][65]:152

After the Revolution, Khomeini opposed allowing women to serve in parliament, likening it to prostitution.

We are against this prostitution. We object to such wrongdoings ... Is progress achieved by sending women to the majlis? Sending women to these centers is nothing but corruption.[66][67][65]:151

Religious philosophy, fiqh, teachings

Khomeini made a number of changes to Shia clerical system. Along with his January 1989 ruling that sharia was subordinate to the revolution, he affirmed against tradition that the fatwa pronounced by a grand ayatollah survived that ayatollah (such as the fatwa to kill Salman Rushdie), and defrocked Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari,[68] a political opponent.

Fiqh

In Fiqh, (Islamic jurisprudence) some scholars have argued Khomeini championed innovative reinterpretations of doctrine, prompted by the challenges of managing a country of 50 million plus.

- Use of Maslaha, or maslahat (`expedient interests` or `public welfare`). This was a common concept among Sunni, but "before the 1979 revolution most" Shi'ite jurists had "rejected maslahat as a dangerous innovation (Bid‘ah)." [69]

- Wider use of "secondary ordinances". Clerics had traditionally argued that the government could issue these "when addressing a narrow range of contractual issues not directly addressed in the Qur'an." Khomeini called for their use to deal with the deadlock between the Majles and the Council of Guardians [70]

- Ijtihad

Esmat

Esmat is perfection through faith. Khomeini believed not only that truly just and divine Islamic government need not wait for the return of the 12th Imam/Mahdi, but that "divinely bestowed freedom from error and sin" (esmat) was not the exclusive property of the prophets and imams. Esmat required "nothing other than perfect faith"[71] and could be achieved by a Muslim who reaches that state. Hamid Dabashi argues Khomeini's theory of Esmat from faith helped "to secure the all-important attribute of infallibility for himself as a member of the awlia' [friend of God] by eliminating the simultaneous theological and Imamological problems of violating the immanent expectation of the Mahdi." [72] Thus by "securing" this "attribute of infallibility for himself", Khomeini reassured Shia Muslims who might otherwise be hesitant about granting him the same ruling authority due the 12 Imams.

The Prophets

Khomeini believed the Prophets have not yet achieved their "purpose". In November 1985 he told radio listeners, "I should say that so far the purpose of the Prophets has seldom been realized. Very little." Aware of the controversial nature of the statement he warned more conservative clerics that "tomorrow court mullahs . . . [should] not say that Khomeini said that the Prophet is incapable of achieving his aims." [73] He also controversially stated that Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad, was superior in status to the prophets of God.[74]

Khomeini's authority and charismatic personality prevented less popular jurists from protesting these changes as un-Islamic Bid‘ah.

Istishhad

Iran–Iraq War

Perhaps the most significant legacy of Khomeini internationally is a broader definition of martyrdom to include Istishhad, or "self-martyrdom".[75] Khomeini believed martyrdom could come not only from "inadvertent" death but "deliberate" as well. While martyrdom has always been celebrated in Islam and martyrs promised a place in heaven, (Q3:169–171) the idea that opportunities for martyrdom were important has not always been so common. Khomeini not only praised the large numbers of young Shia Iranians who became "shahids" during the Iran–Iraq War but asserted the war was "God's hidden gift",[76] or as one scholar of Khomeini put it, "a vital outlet through which Iran's young martyrs experienced mystical transcendence."[77] Khomeini explained:

"If the great martyr (Imam Husayn ibn Ali) ... confined himself to praying ... the great tragedy of Kabala would not have come about ... Among the contemporary ulema, if the great Ayatollah ... Shirazi ... thought like these people [who do not fight for Islam], a war would not have taken place in Iraq ... all those Muslims would not have been martyred." [78]

Death might seem like a tragedy to some but in reality ...

If you have any tie or link binding you to this world in love, try to sever it. This world, despite all its apparent splendor and charm, is too worthless to be loved[79]

Khomeini never wavered from his faith in the war as God's will, and observers have related a number of examples of his impatience with those who tried to convince him to stop it. When the war seemed to become a stalemate with hundreds of thousands killed and civilian areas being attacked by missiles, Khomeini was approached by Ayatollah Mehdi Haeri Yazdi, a grand ayatollah and former student with family ties to Khomeini. He pleaded with Khomeini to find a way to stop the killing saying, "it is not right for Muslims to kill Muslims." Khomeini answered reproachfully, asking him, "Do you also criticize God when he sends an earthquake?"[80] On another occasion a delegation of Muslim heads of state in Tehran to offer to mediate an end to the war were kept waiting for two hours and given no translator when Khomeini finally did talk to them.[81]

Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq

While suicide martyrdom did not win the Iran–Iraq War for Iran, it did spread to Lebanon, where it won victories for the Iraqi Islamic Da'wa party, Shia 'allies' of the Islamic Revolution there. The 1983 bombings against U.S. and French peacekeeping troops by Hizballah killed over 300 and drove the US and French from Lebanon. Another longer bombing campaign did likewise to the Israeli army. Khomeini is credited by some with inspiring these "suicide bombers".[82]

The power of shaheed operations as a military tactic has been described by Shia Lebanese as an equalizer where faith and piety are used to counter superior military power of the Western unbeliever:

You look at it with a Western mentality. You regard it as barbaric and unjustified. We, on the other hand, see it as another means of war, but one which is also harmonious with our religion and beliefs. Take for example, an Israeli warplane or, better still, the American and British air power in the Gulf War. .... The goal of their mission and the outcome of their deeds was to kill and damage enemy positions just like us ... The only difference is that they had at their disposal state-of-the-art and top-of-the-range means and weaponry to achieve their aims. We have the minimum basics ... We ... do not seek material rewards, but heavenly one in the hereafter.[83]

The victory of Hezbollah is known to have inspired Hamas in Palestine,[84] al-Qaeda in its worldwide bombing campaign.[85] In the years after Khomeini's death, "Martyrdom operations" or "suicide bombing" have spread beyond Shia Islam and beyond attacks on military and are now a major force in the Muslim world.[86] According to one estimate, as of early 2008, 1,121 Muslim suicide bombers have blown themselves up in Iraq alone.[87]

Ironically and tragically, in the last few years, thousands of Muslims, particularly Shia, have been victims, not just initiators, of martyrdom operations, with many civilians and even mosques and shrines being targeted, particularly in Iraq.[88] Wahhabi extremist Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi has quoted Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab urging his followers to kill Shi'a of Iraq.[89] In 2007 some of the Shia ulema have responded by declaring suicide bombing haram:

"حتي كساني كه با انتحار ميآيند و ميزنند عدهاي را ميكشند، آن هم به عنوان عمليات انتحاري، اينها در قعر جهنم هستند"

"Even those who kill people with suicide bombing, these shall meet the flames of hell."[90][91]

Shia rituals

Khomeini showed little interest in the rituals of Shia Islam such as the Day of Ashura. Unlike earlier Iranian shahs or the Awadh's nawabs, he never presided over any Ashura observances, nor visited the enormously popular shrine of the eighth Imam in Mashad. This discouraging of popular Shia piety and Shia traditions by Khomeini and his core supporters has been explained by at least one observer as a product of their belief that Islam was first and foremost about Islamic law,[92] and that the revolution itself was of "equal significance" to Battle of Karbala where the Imam Husayn was martyred.[93]

This legacy is reflected in the surprise sometimes shown by foreign Shia hosts in Pakistan and elsewhere when visiting Iranian officials, such as Fawzah Rafsanjani, show their disdain for Shia shrines.[92] And perhaps also in President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's May 2005 statement that "the Iranian revolution was of the same `essence` as Imam Husayn's movement."[93]

Sternness and austerity

Companions and followers of the Ayatollah Khomeini have many stories of his disinterest in his personal wealth and comfort and concern for others.[94][95]

While the Imam was sometimes flexible over doctrine, changing positions on divorce, music, birth control,[96] he was much less accommodating with those he believed to be the enemies of Islam. Khomeini emphasized not only righteous militancy and rage but hatred,

And I am confident that the Iranian people, particularly our youth, will keep alive in their hearts anger and hatred for the criminal Soviet Union and the warmongering United States. This must be until the banner of Islam flies over every house in the world. [97]

Salman Rushdie's apology for his book (following Khomeini's fatwa to kill the author) was rejected by Khomeini, who told Muslims: "Even if Salman Rushdie repents and becomes the most pious man of all time, it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has got, his life and wealth, to send him to Hell." [98][99]

Khomeini felt let down by advisers who he felt had persuaded him to make unwise decisions against his better judgment, appointing people to posts who he later denounced. "I swear to God that I was against appointing Medi Bazargan as the first prime minister, too, but I considered him to be a decent person. I also swear to God that I did not vote for Bani Sadr to become president either. On all these occasions I submitted to the advice of my friends." [100] Before being revised in April 1989,[101] the Iranian constitution called for the supreme leader to be a leading cleric (Marja), something Khomeini says he opposed "since from the very beginning." [102]

He also preached of Islam's essentially serious nature

Allah did not create man so that he could have fun. The aim of creation was for mankind to be put to the test through hardship and prayer. An Islamic regime must be serious in every field. There are no jokes in Islam. There is no humor in Islam. There is no fun in Islam. There can be no fun and joy in whatever is serious. Islam does not allow swimming in the sea and is opposed to radio and television serials. Islam, however, allows marksmanship, horseback riding and competition ...[103][104]

and the all-encompassing nature of Islam, and thus of its law and its government,

Islam and divine governments ... have commandments for everybody, everywhere, at any place, in any condition. If a person were to commit an immoral dirty deed right next to his house, Islamic governments have business with him. .... Islam has rules for every person, even before birth, before his marriage, until his marriages, pregnancy, birth, until upbringing of the child, the education of the adult, until puberty, youth, until old age, until death, into the grave, and beyond the grave.[105]

Muslim and non-Muslim world

Spread of Islam

Khomeini strongly supported the spread of Islam throughout the world.

We shall export our revolution to the whole world. Until the cry 'There is no god but Allah' resounds over the whole world, there will be struggle.[106][107][108][65]:66

Once we have won the war [with Iraq], we shall turn to other wars. For that would not be enough. We have to wage war until all corruption, all disobedience of Islamic law ceases [throughout the world]. The Quran commands: “War! War until victory!” A religion without war is a crippled religion... Allah be praised, our young warriors are putting this command into effect and fighting. They know that to kill the infidels is one of the noblest missions Allah has reserved for mankind.[109][110][111]:43

Not just as a faith but as a state.

Establishing the Islamic state world-wide belong to the great goals of the revolution.[112][113]

Which he believed would replace both capitalism and communism

... `We have often proclaimed this truth in our domestic and foreign policy, namely that we have set as our goal the world-wide spread of the influence of Islam and the suppression of the rule of the world conquerors ... We wish to cause the corrupt roots of Zionism, capitalism and Communism to wither throughout the world. We wish, as does God almighty, to destroy the systems which are based on these three foundations, and to promote the Islamic order of the Prophet ... in the world of arrogance.[114][115][116][117]

Khomeini held these views both prior to and following the revolution. The following was published in 1942 and republished during his years as supreme leader:

Jihad or Holy War, which is for the conquest of [other] countries and kingdoms, becomes incumbent after the formation of the Islamic state in the presence of the Imam or in accordance with his command. Then Islam makes it incumbent on all adult males, provided they are not disabled and incapacitated, to prepare themselves for the conquest of [other] countries so that the writ of Islam is obeyed in every country in the world... those who study Islamic Holy War will understand why Islam wants to conquer the whole world. All the countries conquered by Islam or to be conquered in the future will be marked for everlasting salvation... Islam says: Whatever good there is exists thanks to the sword and in the shadow of the sword! People cannot be made obedient except with the sword! The sword is the key to Paradise, which can be opened only for Holy Warriors! There are hundreds of other [Qur'anic] psalms and Hadiths [sayings of the Prophet] urging Muslims to value war and to fight. Does all that mean that Islam is a religion that prevents men from waging war? I spit upon those foolish souls who make such a claim.[118][119][120][121][111]:43

Unity of the Ummah

Khomeini made efforts to establish unity among Ummah. "During the early days of the Revolution, Khomeini endeavored to bridge the gap between Shiites and Sunnis by forbidding criticizing the Caliphs who preceded Ali — an issue that causes much animosity between the two sects. Also, he declared it permissible for Shiites to pray behind Sunni imams."[122] These measures have been viewed as being legitimised by the Shia practice of taqiyya (dissimulation), in order to maintain Muslim unity and fraternity.[123][124]

Shortly before he died the famous South Asian Islamist Abul Ala Maududi paid Khomeini the compliment of saying he wished he had accomplished what Khomeini had, and that he would have like to have been able to visit Iran to see the revolution for himself.[125]

He supported Unity Week[126] and International Day of Quds.[127] However, according to Sa`id Hawwa in his book al-Khumayniyya, Khomeini's real aim was to spread Shi'ism through the use of such tactics as taqiyya and anti-Zionist rhetoric.[74]

This pan-Islamism did not extend to the Wahhabi regime of Saudi Arabia. Under his leadership the Iranian government cut relation with Saudi Arabia. Khomeini declared that Iran may one day start good diplomatic relation with the US or Iraq but never with Saudi Arabia. Iran did not re-establish diplomatic relation with Saudi Arabia until March 1991, after Khomeini's death.[128]

Shia revival

The Iranian revolution "awakened" Shia around the world, who outside of Iran were subordinate to Sunnis. Shia "became bolder in their demands of rights and representations", and in some instances Khomeini supported them. In Pakistan, he is reported to have told Pakistan military ruler Zia ul-Haq that he would do to al-Haq "what he had done to the Shah" if al-Haq mistreated Shia.[129] When tens of thousands of Shia protested for exemption from Islamic taxes based on Sunni law, al-Haq conceded to their demands.[130]

Shia Islamist groups that sprang up during the 1980s, often "receiving financial and political support from Tehran" include the Amal Movement of Musa al-Sadr and later the Hezbollah movement in Lebanon, Islamic Dawa Party in Iraq, Hizb-e Wahdat in Afghanistan, Tahrik-e Jafaria in Pakistan, al-Wifaq in Bahrain, and the Saudi Hezbollah and al-Haraka al-Islahiya al-Islamiya in Saudi Arabia. Shia were involved in the 1979–80 riots and demonstrations in oil-rich eastern Saudi Arabia, the 1981 Bahraini coup d'état attempt and the 1983 Kuwait bombings.[131]

Neither East nor West

Khomeini strongly opposed alliances with, or imitation of, Eastern (Communist) and Western Bloc (Capitalist) nations.

... in our domestic and foreign policy, ... we have set as our goal the world-wide spread of the influence of Islam ... We wish to cause the corrupt roots of Zionism, capitalism and Communism to wither throughout the world. We wish, as does God almighty, to destroy the systems which are based on these three foundations, and to promote the Islamic order of the Prophet ...[132][115][116][117]

In the Last Message, The Political and Divine Will of His Holiness the Imam Khomeini, there are no less than 21 warnings on the dangers of what the west or east, or of pro-western or pro-eastern agents are either doing, have done or will do to Islam and the rest of the world.[133]

In particular he loathed the United States

... the foremost enemy of Islam ... a terrorist state by nature that has set fire to everything everywhere ... oppression of Muslim nations is the work of the USA ...[134]

and its ally Israel

the international Zionism does not stop short of any crime to achieve its base and greedy desires, crimes that the tongue and pen are ashamed to utter or write.[134]

Khomeini believed that Iran should strive towards self-reliance. Rather siding with one or the other of the world's two blocs (at the time of the revolution), he favored the allying of Muslim states with each other, or rather their union in one state. In his book Islamic Government he hinted governments would soon fall into line if an Islamic government was established.

If the form of government willed by Islam were to come into being, none of the governments now existing in the world would be able to resist it; they would all capitulate.[135]

In the West

While the Eastern or Soviet bloc no longer exists, Khomeini's legacy lives on in the Western world. From the beginning of the Iranian revolution to the time of his death Khomeini's "glowering visage became the virtual face of Islam in Western popular culture" and "inculcated fear and distrust towards Islam."[4] He is said to have made the word `Ayatollah` "a synonym for a dangerous madman ... in popular parlance."[136]His fatwa calling for the death of secular Muslim author Salman Rushdie in particular was seen by some as a deft attempt to create a wedge issue that would prevent Muslims from imitating the West by "dividing Muslims from Westerners along the default lines of culture."[7] The fatwa was greeted with headlines such as one in the popular British newspaper the Daily Mirror referring to Khomeini as "that Mad Mullah",[137] observations in a British magazine that the Ayatollah seemed "a familiar ghost from the past – one of those villainous Muslim clerics, a Faqir of Ipi or a mad Mullah, who used to be portrayed, larger than life, in popular histories of the British Empire",[138] and laments that Khomeini fed the Western stereotype of "the backward, cruel, rigid Muslim, burning books and threatening to kill the blasphemer." [139] The fatwa indicated Khomeini's contempt for the right to life; for the presumption of innocence; for the rule of law; and for national sovereignty, since he ordered Rushdie killed 'wherever he is found' [140]

This was particularly the case in the largest nation of the Western bloc—the United States (or "Great Satan")—where Khomeini and the Islamic Republic are remembered for the American embassy hostage taking and accused of sponsoring hostage-taking and terrorist attacks—especially using the Lebanese Shi'a Islamic group Hezbollah[141][142]—and which continues to apply economic sanctions against Iran. Popular feeling during the hostage-taking was so high in the United States that some Iranians complained that they felt the need to hide their Iranian identity for fear of physical attack even at universities.[143]

Works

- Wilayat al-Faqih

- Forty Hadith (Forty Traditions)

- Adab as Salat (The Disciplines of Prayers)

- Jihade Akbar (The Greater Struggle)

See also

- Ruhollah Khomeini

- Imam's Line

- Iranian Revolution

- Ideology of Iranian Revolution

- Hezbollah

- Oppressors-oppressed distinction

- Islamic scholars

- Politics of Iran

- Mahmoud Taleghani

- Hossein-Ali Montazeri

- Tahrir-ol-vasyleh

Citations

- Islamic Government Islam and Revolution I, Writings and declarations of Imam Khomeini, 1981, p.91

- Hamid Algar, `Development of the Concept of velayat-i faqih since the Islamic Revolution in Iran,` paper presented at London Conference on wilayat al-faqih, in June, 1988] [p.135-8]. Also Ressalat, Tehran, 7 January 1988, online http://gemsofislamism.tripod.com/khomeini_promises_kept.html#Laws_in_Islam Archived 2012-07-08 at Archive.today

- The New Republic "Khamenei vs. Khomeini" by Ali Reza Eshraghi, August 20, 2009, tnr.com dead link Archived 2009-08-21 at the Wayback Machine quotation from article Archived 2011-10-08 at the Wayback Machine accessed 9-June-2010

- Nasr, Vali The Shia Revival, Norton, 2006, p.138

- Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i Islam (1985), p. 193.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1993). Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-520-08503-9.

- Pipes, Daniel (1990). The Rushdie Affair: The Novel, the Ayatollah, and the West. Transaction Publishers. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-4128-3881-8.

- "The People's Shah". 27 August 2000. Archived from the original on 2007-10-15. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001) p.ix

- Abrahamian, Khomeiniism, p.3, 13–16

- 1942 book/pamphlet Kashf al-Asrar quoted in Islam and Revolution, p.170

- "sharghnewspaper.com". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Velayat-e Faqih, Hokumat-e-Eslami or Islamic Government, quoted in Islam and Revolution p.31

- 1970 book Velayat-e Faqih, Hokumat-e-Eslami or Islamic Government, quoted in Islam and Revolution

- Abrahamian, Ervand, A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p.165

- Roy, Olivier (1994). The Failure of Political Islam. translated by Carol Volk. Harvard University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-85043-880-9.

- Gheissari, Ali Democracy in Iran: history and the quest for liberty, Ali Gheissari, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, Oxford University Press, 2006. p. 86-87

- Islamic Government Islam and Revolution I, Writings and declarations of Imam Khomeini, p.137-8

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.116

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.122

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1993). Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. University of California Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-520-08503-9.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1993). Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. University of California Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-520-08503-9.

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.17

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.38

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.2

- Ganji, Sorush and Mesbah Yazdi Archived 2010-06-29 at the Wayback Machine(Persian)

- The principles of Islamic republic from viewpoint of Imam Khomeini in the speeches of the leader Archived 2011-01-28 at the Wayback Machine(Persian)

- About Islamic republic(Persian)

- "Ayatollah Khomeini and the Contemporary Debate on Freedom". Archived from the original on 2007-10-15. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "Democracy? I meant theocracy", by Dr. Jalal Matini, Translation & Introduction by Farhad Mafie, August 5, 2003, The Iranian, http://www.iranian.com/Opinion/2003/August/Khomeini/ Archived 2010-08-25 at the Wayback Machine

- 1979 March 1, quoted in Bakhash, Shaul The Reign of the Ayatollahs, p.72, 73)

- He agreed during his meeting with Karin Samjabi in Paris in November 1978 that the future government of Iran would be `democratic and Islamic`. Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984), p.73

- Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs (1984), p.73

- Khomeini, Islam and Revolution, (1982), p.56

- source: Yusef Sane'i, Velayat-e Faqih, Tehran, 1364/1986, quoted in Moin, Baqer, Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah, Thomas Dunne Books, c2000, p.226

- Fallaci, Oriana. "Interview with Khomeini", New York Times, 7 October 1979.

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.228

- Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001) p.1

- Address by Ayatollah Khomeini on the Occasion of the Iranian New Year,` broadcast 20 March 1979, FBIS-MEA-80-56, 21 March 1980 quoted in Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001) p.113

- Sahifeh Nour (Vol.2, Page 242)

- in Qom, Iran, October 22, 1979, quoted in, The Shah and the Ayatollah : Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution by Fereydoun Hoveyda, Westport, Conn. : Praeger, 2003, p.88

- Khomeini, Islam and Revolution, (1981), p.91

- Khomeini (2013). Islam and revolution : [the writings and declarations of Imam Khomeini]. Routledge. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-136-18934-0.

- Mathewson Denny, Frederick. "Muslim Ethical Trajectories in the Contemporary World" in Religious Ethics, William Schweiker, ed. Blackwell Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0-631-21634-0, p.272

- Abrahamian, Ervand, Tortured Confessions by Ervand Abrahamian, University of California Press, 1999, p.218-9

- Abrahamian, Ervand, Tortured Confessions by Ervand Abrahamian, University of California Press, 1999, p.220-1

- Moin, Khomeini, (2001), p.258

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.134

- economics is for fools (eqtesad mal-e khar ast) from Gheissari, Ali Democracy in Iran: history and the quest for liberty, Ali Gheissari, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, Oxford University Press, 2006, p.87

- (Khomeini July 1979) [quoted in The Government of God p.111. "see the FBIS for typical broadcasts, especially GBIS-MEA-79-L30, July 5, 1979 v.5 n.130, reporting broadcasts of the National Voice of Iran.

- Sorenson, David S. (2009). An Introduction to the Modern Middle East: History, Religion, Political Economy, Politics. Avalon Publishing. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-7867-3251-7.

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism", p.38

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, (p.55)

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.139

- "Economics is for donkeys". Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Abrahamian Iran Between Revolutions (1982), p.479

- Abrahamian, Ervand, History of Modern Iran, Columbia University Press, 2008, p.184

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1993). Khomeinism : essays on the Islamic Republic. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780520085039.

- Abrahamian, Khomeinism, p.42

- Abrahamian Iran Between Revolutions (1982), p.534

- "Law for the Protection and Expansion of Iranian Industry" July 5, 1979 nationalization measure reportedly nationalized most of the privately industry and many non-industrial businesses. Mackey, Iranians, (1986) p.340

- "Stunted and distorted, Stunted and distorted". The Economist. Jan 18, 2003.

- Pithy Aphorism: Wise Sayings and Counsels (by Khomeini), quoted in The Last Great Revolution by Robin Wright c2000, p.152

- Hiro, Dilip (2009). The Iranian Labyrinth: Journeys Through Theocratic Iran and Its Furies. PublicAffairs. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-7867-3871-7.

- Wright, Robin (2010). The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and Transformation in Iran. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-76607-6.

- Speech in Qom quoted in Esfandiari, Iran: Women and Parliaments Under the Monarch and Islamic Republic pp.1–24, quoted in The Last Great Revolution by Robin Wright c2000, p.151

- Beck, Lois; Nashat, Guity (2004). Women in Iran from 1800 to the Islamic Republic. University of Illinois Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-252-07189-8.

- Roy, Olivier (1994). The Failure of Political Islam. translated by Carol Volk. I.B.Tauris. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-85043-880-9.

- Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001), p.61

- `Khomeyni Addresses Majlis Deputies January 24` broadcast 24 January 1983, quoted in Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001), p.129

- Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, p. 463, quoting Khomeini, Jehad-e Akbar (Greater Jihad), pp. 44

- (Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, p. 465

- Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini p.133

- Ofra Bengio; Meir Litvak (8 Nov 2011). The Sunna and Shi'a in History: Division and Ecumenism in the Muslim Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 212. ISBN 9780230370739.

- Ruthven, Malise A Fury For God, Granta, (2002), p.?

- Moin, Khomeini (200)) p.249, 251

- Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini p.123

- `Ayatollah Khomeyni Message to Council of Experts,` broadcast 14 July 1983, FBIS-SAS-83-137, 15 July 1983; Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeinip.130

- Islam and Revolution, p.357

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.120

- Niaz Naik, former Pakistan foreign secretary who accompanied General Zia on trip, in interview with Nasr in Lahore 1990. In Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, 2006, p.141

- "Comment September 19, 2001 8:20". Archived from the original on 2007-08-11. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Hassan, a Hezbollah fighter quoted in Jaber, Hala (1997). Hezbollah: Born with a Vengeance. Columbia University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-231-10834-8.

- Hamas Statement, BBC Summary of World Broadcasts (July 23, 2000)

- `Bin Laden's Sermon for the Eid al-Adha`, Middle East Media Research Institute, Special Dispatch Series, n. 476 (March 5, 2003)

- "Devotion, desire drive youths to 'martyrdom' : Palestinians in pursuit of paradise turn their own bodies into weapons", USA Today, June 26, 2001

- March 14, 2008 The Independent/UK "The Cult of the Suicide Bomber" by Robert Fisk Archived 2011-08-04 at the Wayback Machine "month-long investigation by The Independent, culling four Arabic-language newspapers, official Iraqi statistics, two Beirut news agencies and Western reports"

- According to Scott Atran, in just one year in one Muslim country alone – 2004 in Iraq – there were 400 suicide attacks and 2000 casualties. The Moral Logic and Growth of Suicide Terrorism Archived 2015-06-23 at the Wayback Machine p.131

- Al Jazeera article: "Al-Zarqawi declares war on Iraqi Shia", Accessed Feb 7, 2007. Link Archived 2006-12-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Feb 2007 interview with Christiane Amanpour of CNN: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-02-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Shia-Sunni Conflicts – What are the issues?". Institute of Islamic Studies. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

Ayatollah Yousef Saanei.

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.135

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.136

- Khomeini: life of the Ayatollah, By Baqer Moin

- Rays of the Sun: 83 Stories from the Life of Imam Khomeini (ra) Archived 2011-09-14 at the Wayback Machine "He would never pass on his work to anyone else":

- "Khomeini's REVERSALS of Promises". Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Wright, In the Name of God 1989, p.196

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.284

- Hofstee, Wim; Kooij, A. van der (2013). Religion beyond its Private Role in Modern Society. BRILL. p. 107. ISBN 978-90-04-25785-6.

- letter to Montazeri March 1989. Moin Khomeini, (2000), p.289, p.306-7

- (Moin Khomeini (2000) p.293

- A letter to the president of the Assembly for Revising the Constitution (by Ayatollah Meshkini), setting out his instructions for the future of the leadership" source: Tehran Radio, 4 June 1989, SWB, 6 June 1989] quoted in Moin p.308

- [source: Meeting in Qom "Broadcast by radio Iran from Qom on 20 August 1979." quoted in Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985) p.259)

- Masaeli, Mahmoud (2017). Spirituality and Global Ethics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4438-9362-6.

- (statement to his students in Najaf, 28 September 1977. Found in Khomeini, Sahifeh-ye Nur, vol.I p.234-235) quoted in Dabashi, Theology of Discontent, (1993), p.476-7

- 11 February 1979 (according to Dilip Hiro in The Longest War p.32) p.108 from Excerpts from Speeches and Messages of Imam Khomeini on the Unity of the Muslims.

- Glenn, Cameron; Nada, Garrett (28 August 2015). "Rival Islamic States: ISIS v Iran". Wilson Center. Wilson Center.

- Rieffer-Flanagan, Barbara Ann (2009). "Islamic Realpolitik: Two-Level Iranian Foreign Policy". International Journal on World Peace. 26 (4): 19. ISSN 0742-3640. JSTOR 20752904.

- Lakoff, Sanford. "Making Sense of the Senseless: Politics in a Time of Terrorism". ucsd.edu. University of California San Diego. Archived from the original on 2020-01-08. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Landes, Richard Allen; Landes, Richard (2011). Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-19-975359-8.

- Murawiec, Laurent (2008). The mind of jihad. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521730631.

- Resalat, 25.3.1988) (quoted in The Constitution of Iran by Asghar Schirazi, Tauris, 1997, p.69)

- Bonney, Richard (2004). Jihād : from Qurʼān to Bin Laden. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-230-50142-3.

- Bayan, No.4 (1990), p.8

- Parkes, Aidan (2019). "Power Shifts in the Saudi-Iranian Strategic Competition". Global Security and Intelligence Studies. 4 (1): 32–33. doi:10.18278/gsis.4.1.3. hdl:1885/163729.

- Shakibi, Zhand (2010). Khatami and Gorbachev : politics of change in the Islamic Republic of Iran and the USSR. Tauris Academic Studies. p. 84. ISBN 9781848851399.

- Schirazi, Asghar (1998). The Constitution of Iran: Politics and the State in the Islamic Republic. I. B. Tauris. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-86064-253-1.

- Perry, M.; Negrin, Howard E. (2008). The Theory and Practice of Islamic Terrorism: An Anthology. Springer. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-230-61650-9.

- Khomeini, Ayatollah Ruhollah (2008). "Islam is Not a Religion of Pacifists". In Perry, Marvin; Negrin, Howard E. (eds.). The Theory and Practice of Islamic Terrorism: An Anthology. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 29–32. doi:10.1057/9780230616509_5. ISBN 978-0-230-61650-9.

- Bernstein, Andrew (2017). Capitalist Solutions: A Philosophy of American Moral Dilemmas. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-53010-1.

- Warraq, Ibn (1995). Why I Am Not a Muslim. Prometheus Books. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-59102-011-0.

- Islamonline. Frequently Asked Questions on Iran Archived 2009-11-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Zulkifli (6 Dec 2013). The Struggle of the Shi'is in Indonesia. ANU E Press. p. 109. ISBN 9781925021301.

- Gerhard Böwering; Patricia Crone; Mahan Mirza (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780691134840.

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.138

- Ansari, Hamid, The Narrative of Awakening, The Institute for the Compilation and Publication of the works of the Imam Khomeini, (date?), p.253

- Palestine from the viewpoint of the Imam Khomeini, The Institute for the Compilation and Publication of the works of the Imam Khomeini, (date?), p.137

- Dr Christin Marschall (2003). Iran's Persian Gulf Policy: From Khomeini to Khatami. Taylor & Francis. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-203-41792-8.

- Interview by Vali Nasr with former Pakistani foreign minister Aghan Shahi, Lahore, 1989. from Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.138

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.138-9

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.139

- Bayan, No.4 (1990), p.8)

- The Political and Divine Will of His Holiness the Imam Khomeini Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- The Prologue to the Imam Khomeini's Last Will and Testament Archived 2007-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Khomeini, Islam and Revolution (1981), p.122

- "- Qantara.de – Dialogue with the Islamic World". Archived from the original on 2010-10-05. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- February 15, 1989

- Anthony Harly, "Saving Mr. Rushdie?" Encounter, June 1989, p. 74

- Marzorati, Gerald, "Salman Rushdie: Fiction's Embattled Infidel", The New York Times Magazine, January 29, 1989, quoted in Pipes, The Rushdie Affair, (1990)

- Geoffrey Robertson, Mullahs without mercy, 2009

- Wright, Sacred Rage, (2001), p.28, 33,

- for example the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing see:Hizb'allah in Lebanon : The Politics of the Western Hostage Crisis Magnus Ranstorp, Department of International Relations University of St. Andrews St. Martins Press, New York, 1997, p.54, 117

- "Inside Iran". Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

Bibliography

- Willett, Edward C. ;Ayatollah Khomeini, 2004, Publisher:The Rosen Publishing Group ISBN 0-8239-4465-4

- Bakhash, Shaul (1984). The Reign of the Ayatollahs : Iran and the Islamic Revolution. New York: Basic Books.

- Brumberg, Daniel (2001). Reinventing Khomeini : The Struggle for Reform in Iran. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Harney, Desmond (1998). The priest and the king : an eyewitness account of the Iranian revolution. I.B. Tauris.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1981). Algar, Hamid (translator and editor) (ed.). Islam and Revolution : Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. Berkeley: Mizan Press.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1980). Sayings of the Ayatollah Khomeini : political, philosophical, social, and religious. Bantam.

- Mackey, Sandra (1996). The Iranians : Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-94005-7.

- Moin, Baqer (2000). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. New York: Thomas Dunne Books.

- Schirazi, Asghar (1997). The Constitution of Iran. New York: Tauris.

- Taheri, Amir (1985). The Spirit of Allah. Adler & Adler.

- Wright, Robin (1989). In the Name of God : The Khomeini Decade. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Wright, Robin (2000). The Last Revolution. New York: Knopf.

- Lee, James; The Final Word!: An American Refutes the Sayings of Ayatollah Khomeini, 1984, Publisher:Philosophical Library ISBN 0-8022-2465-2

- Dabashi, Hamid; Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, 2006, Publisher:Transaction Publishers ISBN 1-4128-0516-3

- Hoveyda, Fereydoun ; The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution, 2003, Publisher:Praeger/Greenwood ISBN 0-275-97858-3

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Political thought and legacy of Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ruhollah Khomeini. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Some books by and on Ayatollah Khomeini:

- Sayyid Ruhollah al-Musavi al-Khomeini — Islamic Government (Hukumat-i Islami)

- Sayyid Ruhollah al-Musavi al-Khomeini — The Last Will...

- Extracted from speeches of Ayatollah Rouhollah Mousavi Khomeini

- Books by and or about Rouhollah Khomeini

- Famous letter of Ayatollah Khomeini to Mikhail Gorbachev, dated January 1, 1989. Keyhan Daily.

Pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini:

Critics of Ayatollah Khomeini:

- Dr. Homa Darabi Foundation

- What Happens When Islamists Take Power? The Case of Iran

- Ayatollah Khomeini's Gems of Islamism

- Modern, Democratic Islam: Antithesis to Fundamentalism

- 'America Can't Do A Thing'

- He Knew He Was Right

Biography of Ayatollah Khomeini