Khamovniki District

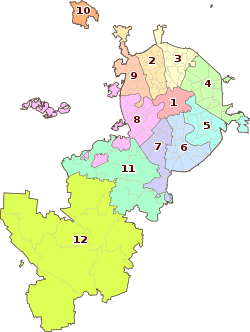

Khamovniki District (Russian: Хамо́вники) is a district of Central Administrative Okrug of the federal city of Moscow, Russia. Population: 102,730 (2010 Census);[1] 97,110 (2002 Census).[2]

The district extends from Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge into the Luzhniki bend of Moskva River; northern boundary with Arbat District follows Znamenka Street, Gogolevsky Boulevard, Sivtsev Vrazhek and Borodinsky Bridge.

The district contains Pushkin Museum, Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Devichye Pole medical campus, Novodevichy Convent and memorial cemetery, Luzhniki Stadium. The stretch of Khamovniki between Boulevard Ring and Garden Ring, known as Golden Mile, is downtown Moscow's most expensive housing area.

From Kremlin to Luzhniki

Within the Boulevards: Volkhonka Street

The central part of Khamovniki is dominated by the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a 2000 replica of 19th century cathedral by Konstantin Thon, destroyed in 1931.

The history of Volkhonka and Znamenka street goes back to the 14th-century court of Sophia of Lithuania, wife of Prince Vasili I and the regent of Moscow after his death, which stood on the site of Pashkov House (Russian State Library) and later housed the Shuysky family.[3] The site of Pushkin Museum was occupied by the royal Coach Yard (Колымажный двор, Kolymazhny Dvor), giving name to existing Kolymazhny Lane. The western boundary of central district, marked by extinct Chertoryi brook on site of present-day Gogol Boulevard, was fortified in 1504 and 1580s. It is believed that Malyuta Skuratov, close associate of Ivan Grozny, lived and was buried here, as indicated by the tombstone found in the 1930s. The area gained importance with the completion of Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge in the 1690s. Throughout the 18th century, it acquired noble residents like Golitsyn, Dolgorukov and Volkonsky families. A state-run pub on Volkonsky property gave name to Volkhonka Street. Most of historical Volkhonka was demolished in 1838 and the 1880s, clearing sites for Christ the Saviour and a riding school,[4] the latter replaced in 1912 by Pushkin Museum. Znamenka Street was razed in the 20th century and is now occupied by Ministry of Defense institutions.

Boulevards to Garden Ring: The Golden Mile

Urbanization of the territories beyond the walls of Bely Gorod (Boulevard Ring) is credited to Ivan Grozny. Ivan allocated these lands to Oprichnina, his own private domain. Very soon, Ivan's faithful associates resettled into oprichnina lands, thus present-day Ostozhenka, Prechistenka and Sivtsev Vrazhek streets initially developed as upper-class neighborhoods and retained this status ever since.[5] Lanes in these neighborhoods (Mansurovsky, Khrushyovsky etc.) are named after original landlords. Ivan's son, childless Fyodor I, instituted extant Conception Monastery between Ostozhenka and Moskva River on the site of old Saint Alexis convent that perished in the Fire of Moscow (1547). Until the 1830s, frequent floods discouraged construction near the river, and the boundary of inhabited territories was 100–200 meters to the north from present-day embankment (see Vodootvodny Canal for more details). Legacy of 16th century survives in historical red and white chambers across Christ the Saviour, restored to their (perceived) original shape.

Upper-class population grew stronger after the Fire of Moscow (1812), when the main streets were rebuilt in Neoclassical architecture by disciples of Matvey Kazakov. Grand 2–3 mansions were more common in Prechistenka, smaller single-story buildings—in Ostozhenka Street; some of them survive to date. However, the territory between facades of Ostozhenka and the embankment were a maze of wooden huts, small factories etc.; this disparity continued until the 1990s, and even today there are many run-down, condemned wooden houses.

The end of 19th century gradually replaced country-style houses with 3–4 story rental buildings. Architectural diversity expanded into Art Nouveau (Lev Kekushev's and William Walcot's mansions, 1900–1903), Russian Revival fantasies (Pertsov Building, 1906–1910,[6] and Tsvetkov House, 1901[7]), Dutch style (Prechistenskaya, 3) and Neoclassical Revival (Mindovsky House by Nikita Lazarev).

Since the 1990s, territory of old Ostozhenka became a construction site. Old blocks are torn down one by one and replaced with modern-looking midrise apartment buildings and offices. The area is now probably the most expensive real estate in Moscow, nicknamed The Golden Mile. In March 2007, advertised starting prices for yet unbuilt properties range from 12,000 to 20,000 USD per square meter (1,100–2,050 USD per square foot).[8]

Beyond Garden Ring: Khamovniki proper

Khamovniki proper is the territory directly beyond Ostozhenka Street (across the Garden Ring). Kham was the name of fabric made by the craftsmen of local sloboda. These craftsmen, originally from Tver, were forced to settle in Moscow in 1624.[9] Extant Church of St. Nicholas in Khamovniki, the center of sloboda, was erected in 1679. In 1708, Peter I added a canvas factory. The textile tradition continued into industrial age; late 19th century textile mills are now converted to offices.

The area is marked by two large historical military institutions: the Grain Warehouses (Провиантские склады, 1827[10]) and Khamovniki Barracks, built in 1807–1809 by Matvey Kazakov on the site of canvas factory, and later expanded. A huge parade ground in front of the barracks now forms part of Komsomolsky Prospekt. The neighborhood also has Leo Tolstoy memorial house (Lva Tostogo Street, 21). Stalinist apartment blocks between Komsomolsky Prospect and Moskva River belong to some of the most expensive real estate in Moscow.

Novodevichy Convent, cemetery and Devichye Pole

For more details on this section, see Novodevichy Convent, Novodevichy Cemetery and Devichye Pole

Fortified Novodevichy Convent, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was established in the early 16th century at the far end of Luzhniki bend to control the river crossing of the old Smolensk road. Extant structures remain virtually unchanged since the 17th century. Adjacent Novodevichy Cemetery, inaugurated in 1898, has been Moscow's most famous burial site (excluding Kremlin Wall Necropolis).

The area between Khamovniki sloboda and the Convent, once a 1.6 kilometer long stretch of green field used for public festivities, is known as Devichye Pole. In 1884–1897, it was developed in a medical campus of Moscow State University. State-funded clinics, built in strict neoclassical manner, were lined on the northern side of Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street; privately funded clinics, on the southern side, present a diversity of styles from Palladian architecture to Russian Revival fantasies. In 1905–1914, the city and private sponsors added new educational properties, including nation's largest college for women. At the same time, Moskva River bank north from the campus developed into a strip of factories; more factories and workers followed during 1915 evacuation of industry and workers from Riga. To accommodate these residents, in the 1920s the Bolshevik administration built the Rationalist Usachevka housing project and Constructivist Kauchuk Factory Club.

Luzhniki

Luzhniki area today is locked between River Moskva and the Moscow Ring Railroad, built in the 20th century. The name is borrowed from an old Luzhniki village, razed to construct the main Stadium.

Urbanization of Luzhniki actually started during World War I. In 1914–1916, Nikolay Vtorov company built a munitions factory, still existing on a triangular lot south-east from present-day Luzhniki Metro Bridge.[11] In 1928, the city built the first wooden Luzhniki Stadium (Chemists' Stadium, 15,000 seats) on the site of present-day main arena. This stadium and Luzhniki village was torn down in the 1950s.[12]

Notable buildings, cultural and educational facilities

Museums

- Pushkin Museum of fine arts, Volkhonka, 12

- Alexander Pushkin Museum, Prechistenka, 12/2

- Leo Tolstoy Museum, Prechistenka, 11

- Leo Tolstoy Estate in Khamovniki, Lva Tolstogo, 21

- Red Chambers (Ostozhenka, 2) and White Chambers (Prechistenka, 1) at Prechistenskye Gates

Churches

- Novodevichy Convent (est. 1582)

- Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (2000)

- Church of St. Nicholas in Khamovniki (1682) www.pravoslavie.ru

- Zachatyevsky Women's Convent (est.1360) Second Zachatyevsky Lane www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Archangel Michael of Devichye Pole clinics (1894–1897, architect M.I. Nikiforov), www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Saint Antipas of Pergamum, Kolymazhny Lane, 8 www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Propet Elijah (1702, architect Ivan Zarudny), Second Obydensky Lane, 6 www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Saint Vlasy, Gagarinsky Lane, 20 www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Dormition, Bolshoy Vlasyevsky Lane, 2/2 www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Raising Lord's Cross in Chisty Vrazhek (1658) First Truzhenikov Lane, 8 www.pravoslavie.ru

- Church of Dmitry Prilutsky (1880), Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street, 6 www.pravoslavie.ru [13]

Public transportation access

- Kropotkinskaya – Pushkin Museum, Christ the Savior

- Smolenskaya (Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya), Smolenskaya (Filyovskaya) – Smolensk Square, Arbat lanes

- Park Kultury-Radialnaya, Park Kultury-Koltsevaya – Khamovniki proper

- Frunzenskaya – Devichye Pole campus

- Sportivnaya – Novodevichy Convent, Luzhniki north

- Vorobyovy Gory – Luzhniki south

References

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- Russian: П.В. Сытин, "Из истории московских улиц", М, 1948 (Sytin), p.70

- Sytin, p.69

- Sytin, pp.168, 173

- Russian: "Древнерусские мотивы в архитектуре Москвы конца XIX – начала XX века (“неорусский стиль”)", "Искусство выбора", N2, 2003 www.mosmodern.race.ru Archived June 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Russian: moskva.kotoroy.net Archived December 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Russian: www.mian.ru Archived March 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Sytin, p.267

- Sytin, p.160

- Russian: "Строители Москвы. Москва начала века" М, ООО О-Мастер, 2001, ISBN 5-9207-0001-7 (Builders of Moscow)

- Russian: Aлександров, Ю.Н., Жуков, К.В., "Силуэты Москвы", М, 1978, c.18

- Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street has an unusually odd numbering; No.6 is actually at its western end, near Novodevichy

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khamovniki. |

- Copy of official site

- Official site

- Photos and webcam of Khamovniki

- History of Khamovniki (in Russian)