Presnensky District

Presnensky District (Russian: Пре́сненский райо́н), commonly called Presnya (Пре́сня), is a district of Central Administrative Okrug of the federal city of Moscow, Russia. Population: 123,284 (2010 Census);[3] 116,979 (2002 Census).[4]

Presnensky District Пресненский район | |

|---|---|

A view of the southern portion of Presnensky District, with the White House of Russia to the right | |

.png) Flag .png) Coat of arms | |

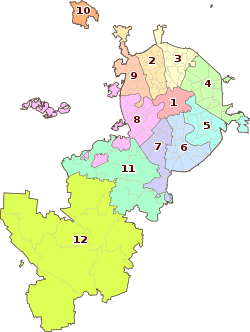

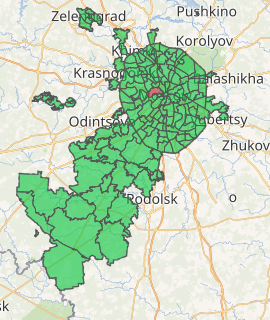

Location of Presnensky District on the map of Moscow | |

| Coordinates: 55°44′48″N 37°32′13″E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Moscow |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018)[1] | 127,462 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| OKTMO ID | 45380000 |

| Website | https://presnya.mos.ru/ |

The district is home to the Moscow Zoo, White House of Russia, Kudrinskaya Square Building, Patriarshy Ponds, Vagankovo Cemetery, and Moscow-City financial district (under construction). It is unusually large and diverse among the Central Okrug Districts, combining affluent residential, administrative and old industrial neighborhoods.

History

This section is based on P.V.Sytin's "History of Moscow Streets" (1948)

The name of Presnya (noun; adjective: Presnensky) district is inherited from the Presnya River, now flowing largely in an underground pipe and entering the Moskva River immediately west of the White House of Russia. Ponds that were set up on Presnya River and its tributaries in the seventeenth century survive as Patriarshy Pond (one of three ponds formerly on the Bubna stream in the Goat Marsh area) and the Moscow Zoo ponds (on the Presnya River proper).

Another small north-south brook flows in piping two kilometers west from Presnya river. Today, it fills four ponds separating the old Presnya district from the Expocenter and Moskva-City developments. This river, named in municipal reports as Studenetz (after a spring on its route) or Vaganskoi (after a cemetery) River[5] flows just under 4 km.[6]

Present-day Krasnaya Presnya street is a part of a historical road connecting Moscow with Novgorod via Volokolamsk since the twelfth century. In the 17th century, lands south of the road were managed by Patriarch Joachim's court, lands north from it belonged to Voskresenskoye settlement, laid down by Tsar Feodor III. This royal village housed a private zoo, a distant predecessor of current Moscow Zoo. Peter I, Feodor's brother a co-ruler, was a frequent guest here. In 1729, Voskresenskoe became property of Vakhtang VI of Kartli, a deposed Georgian king in exile. The memories of Vakhtang and his court remain in the names of Gruzinskaya (Georgian) streets; however, the Georgian community there dispersed within nineteenth century. At the same time, there was and still is a sizable Armenian community; Armenian cemetery remains in Presnensky district (adjacent to Vagankovo Russian Orthodox cemetery).

By 1787, there were four ponds on the Presnya, with a wooden bridge, two dams and a water mill; in 1805, a stone bridge was built. The Studenetz area was a popular picnic destination; the same time, 1798, the famous Trekhgornaya textile factory was built. Entertainment relocated east, closer to Presnya River, and the Kremlin Administrator, Valuev, made a short-lived miracle of converting the dirty banks of the Presnya into an upper-class promenade.

Entertainment continued with the private Studenetz Park and the public Moscow Zoo (1864). But the district itself became an industrial, densely populated working-class area.

In the December 1905 the whole district, the centre of textile industry, was taken over by revolutionary militias; government troops had to bring in artillery to subdue the revolt. Much of the Presnya district was destroyed, and more than one thousand, mostly civilians caught in the fighting, had been killed.[7] In the November 1917, Presnya workers took over the neighborhood again. Martemyan Ryutin was secretary of the local Communist Party in 1932, when the Ryutin Affair occurred; this was one of the last attempts to block Joseph Stalin's rise to power from within the party.

Modern history

In the 1920s, streets of central Presnya were rebuilt into five to six story housing for the workers, although most of the district remained wooden low-rises. Stalinist construction projects concentrated on Garden Ring, while the working-class areas east of it were neglected. In the Leonid Brezhnev era, major administrative buildings were built including the White House of Russia (1975–1981), Comecon Building (1964–1968) and the Center for International Trade (1977–1981), and numerous look-alike apartment blocks.

Moscow-City project, conceived in 1992, commenced after the 1998 crises. At the same time, old industrial properties are torn down and replaced with office space of varying quality. Tram network in Presnensky District, severely cut in 1950s and 1973, was destroyed in 2000–2004 (see photographs with English text tram.rusign.com).

Some of the factories located in the district, such as Trekhgornaya Manufaktura, had been converted in the loft area with offices of fashion and media companies, including Forward Media Group, as well as restaurants, bars and night clubs. Another big manufactory known as Zavod Krasnaya Presnya was pulled down and new residential district appeared instead.

Neighborhoods

- Moscow-City, future financial district of Moscow, also intended to house all administrative offices of City Hall

- Patriarshy Ponds, an affluent residential area within the Garden Ring, the site of Bulgakov's Master and Margarita.

- Tishinskaya Square (Tishinka) is another expensive area on the other side of Garden ring, between the Zoo and Tverskaya

- Shelepikha, a five-story residential area on the western end of Presnensky District, is the next candidate for major redevelopment.

- Yermakova Roshcha, once a park on Studenets Brook, is an industrial area within a triangle of railroads (between Shelepikha and the Moscow International Business Center). So far, the City Hall has no plans to redevelop this area.

References

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- Река Ваганьковский Студенец, in State Document "О состоянии окружающей природной среды города Москвы в 2002 году", 2002

- For more on Studenetz cold spring, which discharges in one of these ponds and gives its name to Studenetz villa and park, and perhaps to the river, see: (Russian) "Памятники архитектуры Москвы. Окрестности старой Москвы", М., 2004 ISBN 5-98051-011-7 (Moscow architectural monuments. Suburbs of old Moscow, 2004)

- Figes, p. 201

Bibliography

- Figes, Orlando. A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 9781847922915.

External links

- Official website of Presnensky district

- 1929 map www.mosmap.narod.ru

- Current map www.napresne.info (Acrobat PDF file)

- Unofficial website of Presnensky District

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Presnensky. |