Adnyamathanha

The Adnyamathanha[1] (Pronounced: /ˈɑːdnjəmʌdənə/) are a contemporary Indigenous Australian people from the Flinders Ranges, South Australia, formed as an aggregate of several distinct peoples. Strictly speaking the ethnonym Adnyamathanha was an alternative name for the Wailpi.[2] Adnyamathanha is also often used as the name of their traditional language, although the language is more commonly called "yura ngarwala" by Adnyamathanha people themselves (being Adnyamathanha for—loosely translated—"our speech").

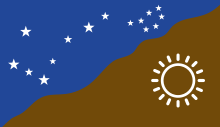

Flag of the Adnyamathanha people | |

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Unknown (110 recorded fluent speakers of Adnyamathanha language) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Flinders Ranges | |

| Languages | |

| Adnyamathanha, English (Australian Aboriginal English, Australian English) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Baptist), traditional beliefs |

Language

Adnyamathanha is a member of the Thura-Yura language family and the only one which still has fluent native speakers.[3]

Country

According to David Horton's map "Aboriginal Australia", the Adnyamathanha lands lie on the west banks of Lake Frome and extend south and west over the northern Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park and northwards over the Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park.[4]

On the northern edges of the Adnyamathanha tribal lands are the Diyari lands, on the western edges are the Kokatha lands. To the south are the Barngarla, Nukunu, and Ngadjuri. To the east are the Malyangapa.

In 2016 Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park was renamed from Flinders Ranges National Park in recognition of its Adnyamathanha heritage. The word ikara means "meeting place" in Adnyamathanha language, and refers in this instance to Wilpena Pound (situated within the park), a traditional meeting place of the Adnyamathanha people.[5]

Social system

The Adnyamathanha constitute an agglomeration of several peoples, the Kuyani, Wailpi, Yardliyawara, and Pilatapa (amongst others), which are traditional groups of the northern Flinders Ranges and some areas around Lake Torrens. The name Adnyamathanha means "rock people" in the Adnyamathanha language, and is a term referring to the Lakes Culture societies living in that area. They share a common identity, which they get from their ancestors; this common bond is their language and culture which is known as Yura Muda. Adnyamathanha people often refer to themselves as 'yura', and non-Aboriginal people as 'udnyu'.

Mythology and astronomy

The origins of the Adnyamathanha are told through creation stories, passed down from generation to generation.[6] The primordial creator figure of the rainbow serpent is, among them, known as akurra.[7]

The Pleiades are known to them as the Makara which are seen as a group of marsupial-like women with pouches, while the Magellanic Clouds are known as Vutha Varkla which are seen as two male lawmen also known as the Vaalnapa.[7][8]

History of contact

In 1851 the first Europeans settled some of the Adnyamathanha land. This led to many conflicts because the Adnyamathanha people were pushed off their land by the Europeans. In response to the settling, Aboriginal people stole sheep, which in turn led to retaliatory killings. Aboriginal stockmen and housekeepers soon became a way of life for the early settlers.[6]

Native title

On 30 March 2009, the Adnyamathanha people were recognised by the Federal Court of Australia as having native title rights over about 41,000 square kilometres (16,000 sq mi) running east from the edge of Lake Torrens, through the northern Flinders Ranges, approaching the South Australian border with New South Wales.

Notable people

- Adam Goodes, four-time All-Australian AFL footballer, stated he is an Adnyamathanha and Narungga man.[9]

- Rebecca Richards, the first Aboriginal Rhodes Scholar, is an Adnyamathanha and Barngarla woman.[10][11]

- Regina McKenzie is an artist who, in 2006, had two pieces acquired by the National Museum of Australia of Adnyamathanha Dreaming Storylines[12] and who, in 2016, was awarded the Peter Rawlinson award for her outstanding contribution to protection of country by the Australian Conservation Foundation.[13]

- Juanella McKenzie, artist and daughter of Regina McKenzie, had two works (containing similar storylines subject matter) acquired by the National Museum of Australia in 2008,[12] and in early 2019 at the age of 29, Juanella was acquired into the National Museum of Scotland with a bark painting she did using traditional methods depicting women's business.[14] She won an Achievement award from TAFE NSW in 2019, a category of the Gili (pronounced kill-ee) Awards which celebrate the achievements of Aboriginal students, as well as the accomplishments of TAFE NSW employees and innovative programs that have empowered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.[15]

See also

- List of Indigenous Australian group names

- Nepabunna, South Australia

Notes

Citations

- Adnyamathanha.

- Tindale 1974, p. 219.

- Clendon 2015, p. 7.

- Horton 1996.

- Dulaney, Bennett & Brown 2016.

- Flinders Ranges National Park 2007.

- Beckett & Hercus 2009, p. 17.

- Curnow 2009.

- Twitter.

- McLoughlin 2016.

- Young Australian of the Year 2012.

- NMoA.

- ACF 2016.

- Arrarru Mathari Artu Mathanha National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Juanella McKenzie shines at TAFE NSW Gili Awards TAFE NSW. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

Sources

- "Adam Goodes (@adamroy37)". Twitter. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "Adnyamathanha". Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Data Archive.

- Austin, Peter (2004). "Diyari (Pama-Nyungan)". In Booij, G. E.; Lehmann, Christian; Mugdan, Joachim (eds.). Morphologie: Ein Internationales Handbuch Zur Flexion und Wortbildung. Volume 2. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1490–1500. ISBN 978-3-110-17278-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckett, Jeremy; Hercus, Luise (2009). The Two Rainbow Serpents Travelling: Mura Track Narratives from the 'Corner Country'. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-1-921-53693-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clendon, Mark (2015). Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar: A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language. University of Adelaide Press. ISBN 978-1-925-26111-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curnow, Paul (June 2009). "Adnyamathanha Night Skies" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of South Australia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dulaney, Michael; Bennett, Tim; Brown, Carmen (1 May 2016). "Flinders Ranges renamed in recognition of traditional Aboriginal owners". ABC News.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Flinders Ranges National Park". Cultural Heritage. Department for Environment and Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- Gason, Samuel (1879) [First published 1874]. "The Dieyerie tribe of Australian Aborigines". In Woods, J. D. (ed.). Native Tribes of South Australia. Adelaide: E. S. Wigg & Son. pp. 253–307.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horton, David R (1996). Aboriginal Australia (Map). Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies – via Trove.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howitt, Alfred William (1904). The native tribes of south-east Australia. Macmillan Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Indigenous leaders Micklo Corpus and Regina McKenzie win Rawlinson award". Australian Conservation Foundation. 25 November 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- McLoughlin, Chris (25 October 2016). "Rhodes Scholar Rebecca Richards aims to improve SA Museum Aboriginal collection". ABC News. Retrieved 20 February 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Rebecca Richards: 2012 Young Australian of the Year". Australian of the Year Awards. National Australia Day Council. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "Regina and Juanella McKenzie collection". Collection Explorer. National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Wailpi (SA)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)