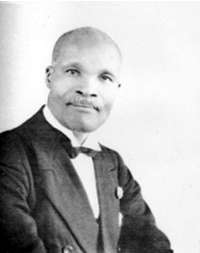

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi (S. E. K Mqhayi, 1 December 1875–29 July 1945) was a Xhosa dramatist, essayist, critic, novelist, historian, biographer, translator and poet whose works are regarded as instrumental in standardising the grammar of isiXhosa and preserving the language in the 20th century.[1]

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 1, 1875 Gqumahashe |

| Died | July 29, 1945 (aged 69) Ntab'ozuko |

| Resting place | Berlin, near King William's Town |

| Pen name | S.E.K. Mqhayi |

| Occupation | Poet, dramatist, essayist, critic, novelist, historian, biographer, translator |

| Language | isiXhosa |

| Nationality | South African |

| Notable works | U-Samson, Ityala Lamawele |

| Notable awards | May Ester Bedford Prize for Bantu literature |

Life

Mqhayi was born in the village of Gqumahashe (an old Mission station) in the Thyume valley near Alice in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa to parents Ziwani Krune Mqhayi and Qashani Bedle on 1 December 1875.[2] Mqhayi's parents were Christians with his father Ziwani known as "a leading man in his church, famous for his counsel, his preaching, and his singing." Mqhayi began his primary schooling in the Thyume Valley. At the age of nine, Mqhayi moved with his father (his mother having died when he was 2 years old) to Centane to stay with his uncle Nzanzana (the headsman of the area) during the witgatboom famine of 1885. Mqhayi recounts the six years he spent in Centane as having had an impact on him and his writing "In those six years I learned much respecting Xhosa life, including the refinements of Xhosa language. … If I had not been at Kentani [sic] for those six years, it seems to me as if I would not have been any help to my nation … it was the means of getting an insight into the national life of my people." When Mqhayi was 15, his uncle died and his father, who had moved to Grahamstown, sent his sister to fetch him. Mqhayi attended Lovedale College where he studied to become a teacher.[3] Mqhayi died in 1945 at Ntab'ozuko, and was buried in Berlin near King Williams Town.

Works

During the 1890s, the printing press had become popular amongst the Black community in South Africa. In 1897, Mqhayi, Allan Kirkland Soga, Tiyo Soga and others launched their own newspaper, Izwi Labantu. In one of his prose writings on Izwi Labantu, Mqhayi reflected on his disappointment with the westernisation of Africa: [1]

Ukuhamba behlolela iinkosi zabo ezibahlawulayo umhlaba. Bahamba nalo ilizwi ukuba lihamba liba yingcambane yokulawula izikhumbani nesizwe, yathi imfuno yayinto nje eyenzelwe ukuba kuviwane ngentetho.[1]

Translation:

Human movement in search of land grabbing land from chiefs. Using the word of God as a tool and instrument to rule kings and nations. An education so inferior became an institution to prepare slaves for new masters.[1]

In 1905, Mqhayi was appointed in the Xhosa Bible Revision Board in 1905. Later, he would help to standardize Xhosa grammar and writing, and then become a full-time author.[4] In 1907 he wrote his first novel in the isiXhosa language, U-Samson an adaption of the biblical story of Samson, which is now lost. In 1914, he published Ityala lamawele ('The Lawsuit of the Twins') an influential isiXhosa novel and an early defence of customary law and Xhosa tradition.[5] In 1925, he wrote a biography of John Knox Bokwe titled uJohn Knox Bokwe: Ibali ngobomi bakhe, which was published by Lovedale Press in 1972. Mqhayi added seven stanzas to Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika which was originally written by Enoch Sontonga in 1927. [6] His autobiography is titled UMqhayi waseNtab'ozuko (Mqhayi of Mount Glory).[7] He wrote Utopia, UDon Jadu in 1929.[8]

Mqhayi was known as ‘Imbongi yakwaGompo’ (the poet of Gompo) and later ‘Imbongi yesizwe’ (the poet of the nation).[6]

Legacy

A youthful Nelson Mandela, who esteemed him "a poet laureate of the African people,"[9] saw Mqhayi at least twice in the flesh, and once, to his infinite pleasure, heard him recite. Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika was adopted by several African states as the national anthem including South Africa, Namibia and Zambia.[6] He won the 1935 May Ester Bedford Prize for Bantu literature.[8]

References

- Smith, David James. Young Mandela. Kent: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010.

- "S E K Mqhayi: Piercing Curtains of Modernity". The Journalist. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Mqhayi, Samuel Edward Krune (c. 1945). A short autobiography of Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi. hdl:10962/19525.

- "The Sociological Imagination of S.E.K Mqhayi". Leo Jonathan Schoots. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Senekal, B. A. "Biografische gegevens". NEDWEB. Archived from the original on 2012-12-06. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- Opland, Jeff. 'The First Novel in Xhosa'. Research in African Literatures, Volume 38, Number 4, Winter 2007, pp. 87–110

- "S E K Mqhayi". Poetry International. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Opland, Jeff (December 22, 2007). "The first novel in Xhosa. (S.E.K. Mqhayi' USamson)". Indiana University Press. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- Barber, Karin (2006). Africa's Hidden Histories: Everyday Literacy and Making the Self. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34729-7.

- Smith 2010, p. 32.

External links

- "S.E.K. MQHAYI - A CALL TO ARMS". Kagablog. October 3, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-19.