Joseph Alter

Joseph S. Alter is an American medical anthropologist known for his research into the modern practice of yoga as exercise, his 2004 book Yoga in Modern India, and the physical and medical culture of South Asia.

Biography

Joseph S. Alter was born in Landour, Uttarakhand, in the north of India.[1] He gained his PhD in 1989 from the University of California at Berkeley.[2]

He is a professor of anthropology at the University of Pittsburgh.[3]

He is known for arguing, in his own words, that "The invention of postural yoga in late nineteenth- and early twentieth century India is directly linked to the reinvention of sport in the context of colonial modernity and also to the increasing use of physical fitness in schools, gymnasiums, clinics, and public institutions."[4][lower-alpha 1] Alter further suggests in his Yoga in Modern India that "Yoga was modernized, medicalized, and transformed [by Yogendra, Kuvalayananda and others] into a system of physical culture."[5] He calls the fusion of yoga's subtle body and its yogic physiology with modern anatomy and physiology a "mistake".[6]

Reception

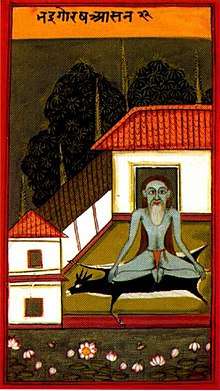

Yoga in Modern India

Alter's 2004 book Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy examines three main themes in the history and practice of yoga in the 20th century: Swami Kuvalayananda's medicalisation of yoga;[8] naturopathic yoga;[9] and the influence of the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh on the development of yoga as exercise.[10]

Stuart Ray Sarbacker, reviewing the book in History of Religions, found the book illuminating on the historical background of yoga, complete with "acerbic asides, including several humorous references to Yoga Journal and its sociological and ideological placement in American consumer society." In his view, the examples were well-researched and brought to life with suitable photographs.[11]

Cecilia Van Hollen, reviewing Yoga in Modern India for The Journal of Asian Studies, writes that it aims to correct the popular tendency to imagine an Indian, spiritual yoga opposed to a corrupt, materialistic American yoga, by examining what Indian texts from the 20th century say about yoga, and constructing a social history of the subject. In her view, what emerges is yoga "as a transnational system of knowledge and practice that emerged in the interstices of colonialism, anticolonial nationalism, and postcolonial Hindu nationalism."[6] She notes that Alter calls the Indian government-led fusion of the yogic subtle body with the physical body of modern anatomy and physiology in the early 20th century a "mistake". All the same, she writes, it helped to transform yoga into what Alter called the "tremendously popular, eminently public, self-disciplinary regimen that produces good health and well being, while always holding out the promise of final liberation."[6] She observes also that Alter shows what "strange bedfellows" yoga and Hindu nationalism were, for while the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) could readily adopt yoga's physical and mental discipline to make men strong, yoga's philosophy is the opposite of "narrowly Hindu".[6]

The yoga scholar Mark Singleton calls the book one of the main (early) studies of the development of modern yoga, like Elizabeth De Michelis's 2004 book examining Vivekananda's "asana-free" yoga in the 1890s and the emergence of postural yoga in the 1920s, but not explaining either why asanas were absent at the start of that period, or how they became rehabilitated. Singleton however endorses Alter's methodology, namely to examine modern yoga's truth claims critically while also exploring the context and reasons for those claims, and considers both De Michelis and Alter to be "critically aware" of modern yoga's "dialectical relationship with tradition".[7] The scholar Andrea R. Jain broadly agrees with Singleton, noting that posture "only became prominent in modern yoga in the early twentieth century as a result of the dialogical exchanges between Indian reformers and nationalists and Americans and Europeans interested in health and fitness".[12]

The book won the 2006 Association for Asian Studies' Coomaraswamy Book Prize.[6]

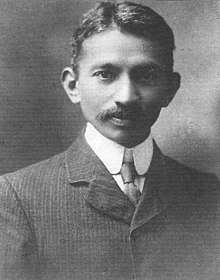

Gandhi's Body: Sex, Diet and the Politics of Nationalism

Alter's Gandhi's Body connected Gandhi's practices of fasting, diet, and exercises with biopolitics and biopower. Alter explains Gandhi's lifelong obsession with food and sex as a way to reach his religious idea of Truth.[13] The American Historical Review said that Alter's book helps researchers study Gandhi's biopolitics without falling into the trap of seeing "faddish" tendencies in him. It said that Alter offers original interpretations of Gandhi's practices, including his sexual experiments.[14]

See also

- Positioning Yoga: balancing acts across cultures, a 2005 book of yoga anthropology by Sarah Strauss

- Yoga Body, a 2010 book about the origins of modern postural yoga by Mark Singleton

- The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace, a 1996 book about the role of Mysore in creating modern postural yoga by Norman Sjoman

Notes

- Other authors who share this approach to yoga as exercise include Norman Sjoman and Mark Singleton.

References

- "Joseph S. Alter". Penguin India. 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Prof. Joseph S. Alter". Modern Yoga Research. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Yoga in Modern India The Body between Science and Philosophy | Joseph S. Alter". Princeton University Press. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Alter, Joseph (2017). "Yoga, Bodybuilding, and Wrestling: Metaphysical Fitness". Asana International Yoga Journal. Retrieved 9 February 2019. from Debra Diamond, ed. (2013). Yoga: The Art of Transformation. Arthur M Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

- Jain, Andrea R. (2014). Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-939026-7. quoting Alter 2004, p. 10

- Van Hollen, Cecilia (May 2007). "Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. By Joseph S. Alter. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004". The Journal of Asian Studies. 66 (2): 562–564. doi:10.1017/s0021911807000757. JSTOR 20203182.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. pp. 4, 1 16. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

- Alter 2004, pp. 73-108.

- Alter 2004, pp. 109–141.

- Alter 2004, pp. 142–177.

- Sarbacker, Stuart Ray (2007). Joseph S. Alter, Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. History of Religions. pp. 278–281.

- Jain, Andrea R. (2012). "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. Butler University, Irwin Library. 25 (1). doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1510.

- Alter, Joseph. Gandhi's Body: Sex, Diet, and the Politics of Nationalism. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. ISBN 9780812204742.

- "The American Historical Review, Volume 106, Issue 5, December 2001, Pages 1784–1785". academic.oup.com.

Bibliography

- Pehlwani : identity, ideology and the body of the Indian wrestler. University of California, Berkeley (thesis). 1989.

- Knowing Dil Das: Stories of a Himalayan Hunter. University of Pennsylvania Press. 1999.

- Gandhi's Body: Sex, Diet and the Politics of Nationalism. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2000.

- The wrestler's body : identity and ideology in north India. University of California Press. 2003.

- Yoga in modern India : the body between science and philosophy. Princeton University Press. 2004.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Asian Medicine and Globalization. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2005.

- Moral Materialism: Sex and Masculinity in Modern India. Penguin. 2011.

External links

- Joseph S. Alter at Penguin India