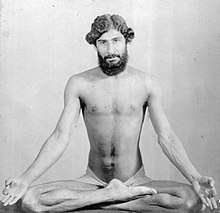

Shri Yogendra

Manibhai Haribhai Desai (1897 – 1989), known as (Shri) Yogendra was an Indian Yoga guru, author, poet, researcher[2] and was one of the important figures in the modern revival of Hatha Yoga, both in India and United States. He was the founder of The Yoga Institute, the oldest organized yoga center in the world, established in 1918.[3][4] He is often referred as the Father of Modern Yoga Renaissance.[5][6] He was one of the figures responsible for reviving the practice of asanas and making yoga accessible to people other than renunciates.[7]

.jpg) Statue of Shri Yogendra | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Manibhai Haribhai Desai 18 November 1897[1] |

| Died | 24 September 1989 (aged 91) |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Spouse | Sita Devi (m.1927) |

| Children | Jayadeva Yogendra, Vijayadev Yogendra |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Amalsad English School, near Surat St. Xavier's College, Mumbai |

| Known for | Pioneering modern yoga |

| Pen name | Mastamani |

| Founder of | The Yoga Institute (1918) |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Paramahamsa Madhavdasji |

The Oglethorpe University has preserved three of his books in the Crypt of Civilization.[8][9][3]

Yogendra innovated modern methods to teach Yoga, initiating research in Yoga, particularly in the field of the Yoga therapy. He authored several books on yoga and started the journal Yoga in 1933. He was also a poet, writing under the nom de plume 'Mastamani'. He translated Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali into Gujarati.[2]

Biography

Early years

Yogendra was born as Manibhai Desai in an Anavil Brahmin family on November 18, 1897 in a village near Surat, Gujarat. He was affectionately called Mogha ("priceless one") in his childhood.[10] His father Haribhai Jivanji Desai was a school teacher. His mother died when he was three years old.

At the age of eighteen in 1916, after distinguishing himself in the Amalsad English School, Yogendra attended St. Xavier's College in Bombay. He felt homesick and fell into depression and lost his interest in studies. At the urging of his roommate, On August 26, 1916, Yogendra visited the Dharamshala of Paramahamsa Madhavadasaji at Madhav Baug, regardless of his robust suspicion of sannyasis and sadhus. However, in Paramahamsa ni Prasadi (1917),[11] he wrote that his misgivings disappeared "as our eyes met" and as it turns out, Madhavadasaji was equally struck by Yogendra's qualities as a capable disciple.[2]

After a period of courtship through letters, Yogendra left his college and went to Madhavadasaji's Ashram in Malsar, near Vadodara in late 1916. He received special attention and it was clear that he was being educated and groomed to be Madhavadasaji's successor. Yogendra learned Yoga, much of the teaching being on the practical and pragmatic use of Yoga and its application in sickness and suffering. His training in the Ashram was centered around yogic 'natural health cures' administered to patients in the ashram's sick ward. Yogendra left the Ashram after more than two years.[2]

Works

On November 25, 1918, Yogendra established The Yoga Institute at the residence of Dadabhai Naoroji at Versova Beach in Bombay (now Mumbai). A year later in 1919, Yogendra left for Europe and the United States, with the aim of popularizing Yoga and set up a branch of the institute, The Yoga Institute of America at Harriman in New York.[12] His system of asanas, which helped to create the modern yoga movement, was influenced by the physical culture of Europeans such as Max Müller.[13] Yogendra began the process of "domesticating" hatha yoga, seeking scientific evidence for yoga's health benefits. This helped to undo the negative image of yoga and asana practice.[14]

In US, Among the people Yogendra met was Benedict Lust, one of the founders of naturopathic medicine. Benedict Lust saw the value of Hatha Yoga for his work and studied it with him. Yogendra stayed there working with a number of Avant-garde doctors such as John Harvey Kellogg and Benedict Lust. Along with the early experiments on Yoga, he finished his first books while in US, Light on Hatha Yoga and a volume on Rabindranath Tagore.[15]

He went back to India less than 5 years later, proceeding to go back to the USA, however thwarted through the restrictive immigration legislation of 1924.[16][17]

Shri Yogendra was a new type of Asian teacher. Neither an ancient chanter of texts nor a renunciate hidden away for years in Himalayan hills, like Vivekananda, he was already partially a Westerner before he ever came to the United States. Growing up in British India, matriculating — before he met his guru — at St. Xavier's College in Bombay, translating the Yogic message into a specific argot, linking his religion-philosophical views to those of Plotinus and Henri Bergson, Shri Yogendra was a blended product of East and West.

The yoga researcher Elliott Goldberg described Yogendra's system of asanas as "safer, more comprehensive, and more effective than Müller's system",[19] and commented that Yogendra "helped strip hatha yoga of .. what he called 'mysticism and inertia'", enabling people to think about asanas "unencumbered by traditional ideology".[20]

Research

In 1921, Yogendra conducted X-Ray studies on Sutra Neti kriyas, a yogic technique to clean the nasal cavity.[21] He conducted research on Prana with Surendranath Dasgupta, an orientalist and philosopher in 1924.[22] In 1930, manuscript 'Yoga Personal Hygiene', authored by Yogendra, is the first book on intricate Yoga processes listing research on the yoga breathing techniques Uddiyana bandha and Pranayama.

Contribution to literature

Shri Yogendra authored his first book named Prabhubhakti (meaning "Devotion to the Lord"), published by Diamond Jubilee Printing Press in Ahmadabad. His second book was Hrudayapushpanjali (meaning "Prayer from the Heart"), a collection of his poetry composed in 1917.[23]

Principal A. B. Yagnik, a Gujarati critic wrote in an article, Poetic Versatility of Shri Yogendra, published in 1979,[23]

We here enter the poet's esthetic world and are delighted with his exquisite reflections. At this stage he might as well have been on the road to Yoga, but not reached there.

— "Poetic Versatility of Shri Yogendra", Journal of The Yoga Institute, November 1979

Shri Yogendra also translated Ravindranath Tagore's Gitanjali from Bengali to Gujarati; it was published in 1918, with Tagore's permission.

He was inspired and influenced by the works of Rabindranath Tagore. The country was full of Indian nationalism, and his 1919 poetry collection Rashtriyagita, speaks of the homeland, the citizens and the struggle for freedom. Other books of his poetry collection includes Pranay Bansi, Sangita Dhvani (2017) and Urmi (2014).[23]

Bibliography

Books on Yoga

Yogendra published many books on yoga, and they have often been reprinted.[24]

- Memorabilia (1926)

- Yoga Asanas Simplified (1928)

- Yoga Physical Education - Volume 1 (1928)

- Yoga Personal Hygiene Simplified (1931)

- Hatha-Yoga Simplified (1931)

- Simple Meditative Postures (1934)

- Rhythmic Exercises (1936)

- Way to Live (1936)

- Breathing Methods (1936)

- Yoga Personal Hygiene (1940)

- Yoga: Physical Education (1956)

- Yoga Essays (1969)

- Facts about Yoga (1971)

- Why Yoga (1976)

- Yoga–Sutras (1978

- Life Problems (1978)

- Guide to Yoga Meditation (1983)

- Yoga in Modern Life

Poetry collections

- Prabhubhakti

- Hrdayapushpanjali

- Pranay Bansi

- Sangita Dhwani (1917)

- Rashtriya Gita (1919)

- Gitanjali of Tagore (1917)

- Urmi (1924)

- Kavi Tagore (1926)

Personal life

.jpg)

He married Sita Devi in 1927. The couple had two sons, named Jayadeva Yogendra and Vijayadev Yogendra.[25]

Yogendra died on September 25, 1989 at the age of 91 in Mumbai.[26][25]

Legacy

In 1994, The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation renamed the TPS 5 Prabhat Colony as Yogendra Marg (road) after Yogendra.

A Chowk named Shri Yogendra Chowk located in Santacruz, Mumbai, is named after him, was inaugurated by Suresh Prabhu, the Minister of Railways, Govt. of India in April 2017.[27]

His son Vijayadev Yogendra (1930–2005) immigrated to Australia and continued his father's work through the establishment of the Total Health and Education Foundation in Melbourne and The School of Total Education in Warwick, Queensland.[28]

References

- Singleton, Mark; Byrne, Jean, eds. (June 30, 2008). Yoga in the Modern World: Contemporary Perspectives. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 9781134055203.

- Goldberg 2016, pp. 2–74.

- "World's oldest yoga centre still going strong". The Times of India. February 5, 2015.

- Jhangiani, Diipti (November 22, 2013). "Neighbourhood Haven The Yoga Institute". DNA India.

- Mishra, Debashree (July 3, 2016). "Once Upon A Time: From 1918, this Yoga institute has been teaching generations, creating history". Mumbai: Indian Express.

- Sadhaka (2015). A Spiritual Path That Led to Arunachala. p. 11.

- Barrett, Jennifer (December 1997). "Householders Yoga". Yoga Journal. Active Interest Media (137): 24.

- Knox, Raymond Collyer; Friess, Horace Leland (1941). The Review of Religion, Volumes 6-7. Columbia University Press. p. 416.

- Unger, Gerhard (1976). "November 18 is the 80th Birthday of Shri Yogendra, the grand old man of Yoga". The Illustrated Weekly of India. Bennett, Coleman & Company, The Times of India.

- Rodrigues, Santan (1997). The Householder Yogi Life of Shri Yogendra. p. 3. ISBN 978-8185053059.

- Rodrigues, Santan (1997). The Householder Yogi Life of Shri Yogendra. p. 32. ISBN 978-8185053059.

- Caycedo, Alfonso (1966). India of yogis. National Publishing House, the University of Michigan. p. 194.

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2017). "The Revival of Yoga in Contemporary India" (PDF). Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. 1. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.253. ISBN 9780199340378.

- Singleton 2010, pp. 116–117.

- Quinn, Edward (2014). Critical Companion to George Orwell Critical Companion Encyclopedia of World Religions Series Facts on File library of world literature. Infobase Publishing. p. 515. ISBN 9781438108735.

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010-09-21). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 3159. ISBN 9781598842043.

- Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism Encyclopedia of World Religions Facts on File library of religion and mythology. Infobase Publishing. p. 263. ISBN 9780816075645.

- Kripal, Jeffrey J.; Shuck, Glenn (2005). "The American Mission of Shri Yogendra and Paramhansa Yogananda". On the Edge of the Future: Esalen and the Evolution of American Culture Religion in North America. Indiana University Press: 64, 65, 66. ISBN 0253345561.

- Goldberg 2016, p. 40.

- Goldberg 2016, p. 43.

- Guha, Kunal (January 7, 2018). "Relative Value: A Century of Wellness". Mumbai Mirror.

- "Full text of "Mircea Eliade And Surendranath Dasgupta Guggenbuehl C"". archive.org. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Rodrigues, Santan (1997). The Householder Yogi Life of Shri Yogendra. pp. 52, 53, 54, 60. ISBN 978-8185053059.

- "inauthor:"Shri Yogendra"". Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- Raj, Ashok (April 1, 2010). The Life and Times of Baba Ramdev. Hay House. ISBN 9789381398098.

- "Yoga pioneer, Yogendra, dead". The Times of India. September 27, 1989.

- "Centenary logo of The Yoga Institute, Santacruz unveiled on the 88th birthday of living Yogi Dr. Jayadeva Yogendra Shri Yogendra Chowk also commemorated". indianshowbiz.com. April 30, 2017.

- "A Story of Vision and Commitment". The School of Total Education. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

Sources

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781620555682.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Rodrigues, Santan (1997). The Householder Yogi – Life Of Shri Yogendra.

- Yogendra, Vijayadev (1972). Glimpses from the life of Shri Yogendra : Father of Yoga Renaissance. Yoga Education Centre, Melbourne. OCLC 220335795.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singleton, Mark; Goldberg, Ellen (2013). Gurus of Modern Yoga. Oxford University Press. pp. 60–75. ISBN 9780199938711.

- Yogendra, Vijayadev (1977). Shri Yogendra, The householder Yogi. The Yoga Institute. OCLC 83123746.

External links

- Official website of The Yoga Institute

- The First Yoga Class on Do Yoga (by Doug Keller)

- Yogendra on Yoga Vidya (in German)