Josefa Segovia

Josefa Segovia, also known as Juanita or Josefa Loaiza, was a Mexican-American woman who was executed by hanging in Downieville, California on July 5, 1851.[1] She was found guilty of murdering a local miner, Frederick Cannon. She is known to be the first and only woman to be hanged in California.[2]

Early life and controversy about her name

Not much is known about the early life of Josefa Segovia. The date of her birth is unknown.[3] Josefa's actual name has been a topic of debate among historians and scholars. Before the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, most scholars stated that Josefa had no recorded last name. In Gordon Young's Days of 49, he says that her name was "Juanita".[4] Hubert Bancroft in his account of the event[5]s at Downieville refers to Segovia as either "The Mexican" or "the little woman" but used Juanita during his description of her trial.[6] Historian Rodolpho F. Acuna stated her name was Juana Loaiza citing an 1877 Schedule of Mexican Claims Against the United States that listed a Jose Maria Loiza as claiming damages for the lynching of his wife. However, the name does not show up in the 1850 census, which suggests that the claim may have been fraudulent.[7] In 1976, Martha Cotera, an influential activist of both the Chicano Movement and Chicana Feminist Movement, informed Chicano scholars that her last name was Segovia.[2]

Adult life

Family

Irene I. Blea's book U.S. Chicanas and Latinas in a Historical Context claims that Josefa was a Sonoran and of good character.[3] She was about 26 years old at the time of her death.[3] Kerry Segrave recounts Josefa Segovia's life in Downieville, California, also known as "The Forks" for its location at the north fork of the Yuba River. She lived with a Mexican gambler, José, in a small house on the main street of town. It is not completely clear if they were married or not.[8]

Reputation in Downieville

Josefa was probably not married to José, but she did live with him. Therefore, she received a bad reputation.[3] According to one account, Juanita (read Josefa) was slender and barely five feet (1.5 m) tall.[4] The same account states that Josefa was beautiful, vivacious and intelligent. Some say that she was not at all disliked in the mining camp in Downieville.[4]

Downie relates the story in the following fashion. Juanita had accompanied her partner to Downieville from Mexico and both lived in an adobe house. Downie states, "Whether she was his wife or not makes no difference in this story." He further describes her figure as "richly developed and in strict proportions." Only her temper was "not well balanced." Celebrating the Fourth of July, Cannon and companions were returning from the dram shop at a late hour, with Cannon staggering from the influence of liquor. Along the way, he stumbled through the door of the adobe hut. His friends quickly pulled him back outside and they proceeded home. Mortified the next morning of his embarrassing blunder, he proceeded to the hut to offer an apology in Spanish. This did not go well with the Mexican couple, and Juanita grew angry. In a rage, she drew a knife and stabbed Cannon. Soon a "mob of infuriated men" gathered, ready to invoke the "miner's law" of a "Life for Life". Only a Mr. Thayer came to her defense, but to no avail as she was quickly tried and found guilty. A scaffold was erected and the "howling blood-thirsty mob...cried for vengeance" according to Downie. Downie states Juanita retold the story of the "unfortunate incident", how she had been "provoked" and if done so again would "repeat her act." She then took the rope, placed the noose around her neck, said "Adiós Señores!" and "leaped from the scaffold into eternity." Downie concludes by stating "it was one of those blots that stained the early history of California." [9]

Social and racial environment for Latinos in California

In 1835, Andrew Jackson tried to buy California for $3.5 million, but Mexico refused the offer. Ten years later, James K. Polk suggested annexing Texas, but also put California as a high priority on his list of territory to acquire.[10] The US and Mexico went to war on May 13, 1846. Two years later on February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed.[10] What neither the U.S. or Mexico realized was that 9 days earlier, gold had been found in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.[10] It is estimated that between 1848 and 1852, as many as 25,000 Mexicans migrated to California to mine.[11] In the fall of 1848, as many as 3,000 Mexicans migrated to the mining regions. Often, they traveled as entire families.[12] After hearing of the gold, thousands of American men borrowed money, mortgaged their homes, or spent their life savings to travel to California and take advantage of the opportunity to find gold. Because society at the time was based on a waged labor, the idea that a person could obtain wealth by finding gold became irresistible.[10] By 1849, the population of non-native Californians grew to over 100,000. Two-thirds of this non-native population were Americans. Despite the fact that the work of mining was the hardest kind of labor, the promise of gold drew miners west every year.[12]

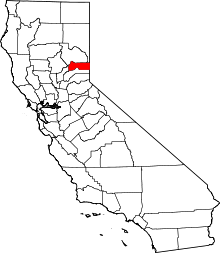

In 1848, when the California Gold Rush began, the population of the state was a Mexican majority. However, this Mexican population fell to 15% by 1850 and to 4% by 1870.[13] Northern California, where Downieville is located, received the majority of the Anglo migration during the beginning of the Gold Rush. The Mexican majority in 1848 allowed for many successes for early racial relations. For example, all state laws and regulations were to be translated into Spanish.[13][14] [14]

Trial

The American mining population in Downieville was enraged by Cannon's death. Josefa was put on trial the next day, and the jury consisted of Cannon's friends and companions while the rest of Downieville waited for the results.[15] Supposedly, a physician, Dr. Cyrus D. Aiken, testified that Josefa was not in a fit condition to be hanged [4] Protests immediately followed the doctor's testimony and he was forced from the stand and from the town. Moments later, Josefa was found guilty of the murder of Cannon. Also, Mr. Thayer, a lawyer from Nevada attempted to testify against the execution of Juanita but was beaten off the stand.[4] Reportedly, he asked for a fair trial for Juanita to see if a murder had really been committed.[15]

Death: July 5, 1851

For the lynching, a scaffold was constructed on the bridge over the Yuba River.[8] The town came to stand on the banks of the river and watch her execution. It was an important event to lessen the anger of the townspeople over Cannon's death. Josefa was hanged immediately following the trial, and some accounts say that her last words before she was executed were "Adiós Señores".[16] She is widely known to be the first woman to be executed by hanging in California [8] Mr. Manly wrote, "Juanita went calmly to her death. She wore a Panama hat, and after mounting the platform she removed it, tossed it to a friend in the crowd, whose nickname was 'Oregon,' with the remark, 'Adios, amigo.' Then she adjusted the noose to her own neck, raising her long, loose tresses carefully in order to fix the rope firmly in its place; and then, with a smile and wave of her hand to the bloodthirsty crowd present, she stepped calmly from the plank into eternity. Singularly enough, her body rests side by side, in the cemetery on the hill, with that of the man whose life she had taken." Mr. Manly's book is generally a first person account of his experiences migrating to California to mine for gold. Although he did mine for gold near Downieville in 1851, he, by his own account, was not in Downieville on the dates in question. He does not cite the source for his version of the events though it seems conceivable he heard eye-witness accounts.

Some witnesses recalled Juanita saying before she died: "'I would do the same again if I was so provoked.'".[7] This is one of many characteristics pointed out by some who are of the opinion that she must have been an aggressive woman. This has been used to advance the idea that those who lynched her may have been right that she had murdered Joe the miner when he was not actually threatening her safety. Another fact brought up to support this idea is that the townsfolk noted that she was quick to anger. Due to conflicting witness statements and vague details some modern commentators still fall on the side of Frederick Cannon.[7] This shows that while most current thoughts about the incident take race and gender status as strong indicators that the story given by the vigilantes was most likely inaccurate some today still believe that their actions were justified.

References

- Ochoa, Oscar (2015). The California Crucible: Frontier narratives and the lynching of Josefa Segovia. Dominguez Hills, CA: California State University. p. 1.

- Gutierrez, Margo, and Matt S. Meier. Encyclopedia of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Greenwood, 2000. Print. p. 135-136.

- Blea, Irene I. U.S. Chicanas and Latinas Within a Global Context: Women of Color at the Fourth World Women's Conference. Praeger, 1997. 89–90. eBook.

- Young, Gordon. "Days of 49'." Popular Tribunals[Downieville, California] 1851, Volume 1 Pg. 417-557. Web. 4 Nov. 2013.

- https://www.hhhistory.com/2016/08/josefa-segovia-pretty-juanita.html

- Bancroft, Hubert. "The Downieville Tragedy." The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. San Francisco: The History Company. 1887. <https://archive.org/stream/cihm_14187#page/n7/mode/2up>

- Rubio, J'Aime. "First Recorded Hanging of a Woman in California History." Dreaming Casually, 07 08 2013. Web. 12 Dec. 2013. <http://dreamingcasuallypoetry.blogspot.com/2013/07/first-lynching-of-woman-in-california.html>

- Segrave, Kerry. Lynchings of Women in the United States: The Recorded Cases, 1851–1946. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010. 21-22. eBook. p. 21-22.

- Downie, William (1971). Hunting for Gold. Palo Alto: American West Publishing Company. pp. 146–153. ISBN 0-910118-22-1.

- "The California Gold Rush." PBS. PBS, 13 Sept. 2006. Web. 05 Dec. 2013. <https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/goldrush/peopleevents/e_goldrush.html>

- Carrigan, William D., and Clive Webb. "The Lynching of Persons of Mexican Origin or Descent in the United States, 1848 To 1928." Journal of Social History. 37.2 (2003): n. page. Web.

- "Mexicans in the Gold Rush." PBS. PBS, 13 Sept. 2006. Web. 04 Dec. 2013. <https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/goldrush/peopleevents/p_mexicans.html>

- California Department of Parks and Recreation. California Department of Parks and Recreation, 1988. Print. <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2013-12-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>.

- Rosales, Francisco Arturo. Chicano! the History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. 2 Revised Edition. Arte Publico Press, 1997. 14. Print.

- "Woman up in the west". Fairbanks Weekly News – Miner [Alaska], January 21, 1921, p. 15.

- Popular Tribunals. Vol. i, p. 557 seq.