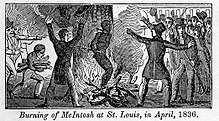

Burning of Francis McIntosh

The Burning of Francis McIntosh was the lynching of a mulatto boatman in St. Louis, Missouri on April 28, 1836.[1]

Lynching

Francis L. McIntosh, aged twenty-six,[2] of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who worked as a porter and a cook on the steamboat Flora, arrived in St. Louis on April 28.[3] McIntosh departed the boat in the morning to visit an African-American chambermaid who worked aboard the Lady Jackson, which had docked the same day.[3] According to the captain of the Flora, as McIntosh departed the boat, two police officers were chasing another sailor (who had been involved in a fight) and requested McIntosh's assistance in stopping him.[3] McIntosh did not assist the officers, and he was arrested for interfering in the apprehension.[3] In the second version of events, the two sailors had been drinking and had insulted the officers, and McIntosh refused to assist in arresting the pair.[3] According to St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, Deputy Constable William Mull arrested McIntosh the afternoon of the 28th for helping two Flora deckhands escape from Mull's custody. On their way to jail, the two met George Hammond, deputy sheriff, who assisted Mull in escorting McIntosh to jail.[4]

When charged with breach of the peace by a justice of the peace, McIntosh asked the two arresting officers how long he would have to remain in jail.[3] One told him that he would serve five years in prison for the crime, and McIntosh then stabbed both officers, killing one and seriously injuring the other.[1][3] McIntosh then fled down Market Street to Walnut, scaled a garden fence, and hid in an outhouse. A man in the crowd that had gathered outside smashed in the door, knocked down McIntosh, and took his knife. The crowd then took McIntosh to jail, where Sheriff James Brotherton locked him up.[4] A white mob soon broke into the jail and removed McIntosh.[1] The mob then took him to the outskirts of town (near the present-day intersection of Seventh and Chestnut streets in Downtown St. Louis), chained him to a locust tree, and piled wood around and up to his knees.[1] When the mob lit the wood with a hot brand, McIntosh asked the crowd to shoot him, then began to sing hymns.[3] When one in the crowd said that he had died, McIntosh reportedly replied, "No, no — I feel as much as any of you. Shoot me! Shoot me!"[3] After at most twenty minutes, McIntosh died.[3] Estimates for the number present at the lynching range in the hundreds, and include an alderman who threatened to shoot anyone who attempted to stop the lynching.[5] During the night, an elderly African-American man was paid to keep the fire lit, and the mob dispersed.[3] The next day, on April 29, a group of boys threw rocks at the corpse in an attempt to break the skull.[3]

When a grand jury was convened to investigate the lynching on May 16, overseen by Judge Luke E. Lawless, most local newspapers and the presiding judge encouraged no indictment for the crime, and no one was ever charged or convicted.[5][6] Judge Lawless stated in his charge to the jury that if individuals could be found guilty, they should be prosecuted. However, he suggested no judicial action if this was a mass phenomenon.[7] The judge also remarked in court that McIntosh's actions were an example of the "atrocities committed in this and other states by individuals of negro blood against their white brethren," and that with the rise of abolitionism, "the free negro has been converted into a deadly enemy."[5][8] The jury was also misinformed by the judge that McIntosh was a pawn of local abolitionists, particularly Elijah Lovejoy, the publisher of a known abolitionist newspaper. Many in the East and St. Louis itself condemned Judge Lawless' actions during the trial.[7]

Aftermath

In the weeks after the lynching, several abolitionists condemned the events, including newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy.[3][9] Lovejoy ran the abolitionist, temperance, and anti-Catholic newspaper, St. Louis Observer. The Observer header on May 5, 1836 suggested that the lynching of McIntosh effectively ended the rule of Law and Constitution in St. Louis.[7] As a result of mob pressure, Lovejoy was forced to move from St. Louis to Alton, Illinois, where he was shot and killed while defending his printing press from a mob in November 1837.[5] One New York abolitionist newspaper, The Emancipator, noted that "the circumstances attending the burning of a negro alive, at the West, are known.... The Spaniards may have murdered monks by the score, the Mexicans may have shot prisoners by the dozen, but roasting alive before a slow fire is a practice nowhere except among free, enlightened, high-minded Americans."[3]

In January 1838, future President Abraham Lincoln used the lynching as an example in his address at the Lyceum.[1]

Turn, then, to that horror-striking scene at St. Louis. A single victim was only sacrificed there. His story is very short; and is, perhaps, the most highly tragic, if anything of its length, that has ever been witnessed in real life. A mulatto man, by the name of McIntosh, was seized in the street, dragged to the suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within a single hour from the time he had been a freeman, attending to his own business, and at peace with the world.

— Abraham Lincoln, Address at the Lyceum, January 27, 1838

No other state legislator in Illinois or Missouri condemned the mob action.[3] Shortly after the lynching, a St. Louis newspaper, the Missouri Republican, noted that abolitionists were attempting to gather McIntosh's remains in an effort to bring them to the Eastern United States, as a symbol of the evils of slavery.[3] In the years following the lynching, visitors to the city (often from McIntosh's home town of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) frequented the tree and removed parts of it as memorial keepsakes.[1]

See also

- History of St. Louis, Missouri

Notes

- Wright, John A. (2002). Discovering African American St. Louis: a Guide to Historic Sites (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press. p. 17. ISBN 1-883982-45-6.

- Van Ravenswaay, Charles (1991). St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1754-1865. Missouri History Museum. p. 283. ISBN 0-252-01915-6.

- Simon, Paul (1994). Freedom's Champion: Elijah Lovejoy. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 45–50. ISBN 0-8093-1940-3.

- Van Ravenswaay, Charles (1991). St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People. Missouri Historical Society.

- Graff, Daniel A. (2004). "Race, Citizenship, and the Origins of Organized Labor in Antebellum St. Louis". In Spencer, Thomas Morris (ed.). The Other Missouri History: Populists, Prostitutes, and Regular Folk. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9780826264305.

- Julius, Kevin C. (2004). The Abolitionist Decade, 1829-1839: a Year-by-Year History of Early Events in the Antislavery Movement. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9780826264305.

- Schwarzbach, F.S. (1980). "The burning of francis L. McIntosh: A note to a dickens letter from america". Dickens Studies Newsletter. 11 (2). ProQuest 1298044848.

- Pallitto, Robert M., ed. (2011). "2:16 Jury Charge by Judge Luke Lawless, 1836, in prosecution of lynchers". Torture and State Violence in the United States: a Short Documentary History. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 62–63.

- Lovejoy, Elijah (May 5, 1836). "Awful Murder and Savage Barbarity". St. Louis Observer. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

Further reading

- Gourevitch, Philip (March 15, 2016). "Abraham Lincoln Warned Us About Donald Trump". The New Yorker.