San José Castle (Guatemala City)

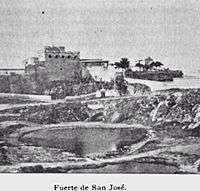

San José Castle -also known as Castillo de San José in Spanish- was opened to the public on 25 May 1846 on the «Buena Vista Hill» on the southeast of Guatemala City by general Rafael Carrera government; it was also known as «Carrera Castle».[1] San José Fort was located where later Guatemalan administrations built a new city Hall, a National Theater and part of the Bolivar Avenue. The fort had a shooting range for the soldiers, ammunition warehouses, horses, diners and a small pond that was called "Soldier's Pond". [1]

| San José Castle | |

|---|---|

Castillo de San José Buena Vista Brigada de Artilleria Santa Barbara Museo del Ejército | |

San José Castle in 1875. Photo by Eadweard Muybridge | |

Location within Guatemala | |

| Former names | Carrera Fort or Santa Barbara Fort |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Military Fort |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 14.6430°N 90.5155°W |

| Construction started | 1843 |

| Construction stopped | March 19, 1846 |

| Owner | Guatemalan Army director Rafael Carrera |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | José María Cervantes |

History

Construction

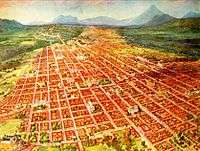

The fort was located on the south extreme of Guatemala City and was placed at least 20 m above the level of the rest of the valley, giving it a great military advantage during the 19th century, when it was built as it could cover the whole valley and the city.[2]

During the first invasion of Honduran general Francisco Morazán in 1829, the Buena Vista hill was used to strategically place some troops, which eventually helped for the defeat of the Guatemalan Army and in the expulsion of the regular clergy and the conservative part conformed by the Aycinena family.[3] and the imposition of the liberal regime led by Dr.Mariano Gálvez in the Central American State of Guatemala.[3] After the events that led Rafael Carrera to power in 1839 and after the failed second invasion of Morazán in 1840, general Carrera considered of the utmost importance to protect Guatemala City building a series of fortresses around it; San José Fort was the first one built.[2]

In 1843, Carrera appointed the city builder José María Cervantes to design and build a fort on the Buena Vista hill. Construction took about three years, and it was done as fast as possible due to the constant revolts in the country, like the ones of the Lucios and of the Cruz brothers in eastern Guatemala.[2] Originally, the fort had a bridge, it was surrounded by water and had impressive protective walls.[2]

Carrera opened the fort on 25 May 1846, with a mass in the old El Calvario church, which used to be close by the fort; a procession of the Virgin of Santa Barbabra left the church and ended at the Fort wall, where it was blessed and remained during the time the fort was active. A year later, San José fort was already the most important ammunition warehouse in Guatemala.[2]

Military service

By 1852 the name «San José» was already common for all the Guatemala City inhabitants, even though the military referred to it as the "Santa Barbara Artillery Brigade". By then, Carrera already used the building as prison for those that opposed his regime. In 1854, after destroying and moving to Guatemala the artillery of Honduras Omoa Castle, Carrera used San José to settle all the equipment.[Note 1] In 1866 sergeant Emilio Rascón was appointed as fort commander, establishing very rigid discipline.[2]

Tragic week April 9–14, 1920

April 9, 1920

On April 8, 1920, president Manuel Estrada Cabrera was declared mentally unfit to continue in office, after 22 years. He resisted this designation and settled for a fight from his residence in "La Palma", which was a large enclosed area with roads crossing both ways, without any real aspect of park or garden arrangement. Tumbled together in a group were some small buildings, painted in the crudest colors; each house appeared to be built for some particular purpose: one was the dining room, another the kitchen, a writing room, and so on. The structure had little open spaces, was blazed in the sun and had wonderful landscapes painted on the walls. At a little distance were straw-thatched huts with a lone broad bench used for bed and table for servants and soldiers.[5]

On April 9, 1920, Guatemala City was awakened with machine-gun fire and shells dropping close in every quarter of the city. In "La Palma" French field-howitzers and seventy-fives with anti-aircraft sights, quick firing guns and machine guns were drawn up;[6] on the other hand, in Guatemala City streets were deserted and bloodshed commenced in earnest.[7] The Unionists were caught off-guard: their organization was deficient, and they had almost no weapons, but they were able to remedy the situation. Government buildings were systematically plundered and ransacked and they got arms and ammunition from the most unlikely places; this way they got knives, machetes, saloon rifles, shotguns, axes and crowbars. With enthusiasm, all men raised barricades and dug trenches in the streets.[8]

The shooting at first accounted for as many friends as enemies, but after white badges bearing the name "Unionista" were distributed, the fire was more effective.[8] A few hours later all males in the city were wearing that token in their hat, and there were even some that had a portrait of the new president on their chest. On the government side, steady fire was maintained from "La Palma" and the two forts of San José and Matamoros. Cars with the Red Cross flag dashed incessantly, carrying a sister on the footboard with her medical supplies on one hand and a machete stuck in her belt.[9]

After the combats, the water supply pipes and electric cables were damaged, leaving the city in darkness from the first night; telephone and telegraph were also out of order. The wildest rumors were the only source of news while bullets whistled about one's ears. It was a revolution, which, thanks to the modern weapons, was really hard fought.[10]

April 10–13, 1920

During these days there was reason to fear that the Cabrerists might attempt to outflank the city and fall upon the revolutionaries from the rear, causing each to defend himself as best he could in the confusion;[11] and several times a truce was proclaimed, only to be broken a few minutes later.[12]

April 14, 1920

Combat lasted until San José fort fell due partly to hunger and partly to buying the defenders, for the fort commanded the position at "La Palma" entirely. By the following afternoon the revolutionaries were absolute masters of the situation. The firing gradually ceased and Estrada Cabrera surrendered, along with the remainder of his forces, numbering about five thousand.

See also

- Manuel Estrada Cabrera

- Federico Ponce Vaides

- Rafael Carrera

Notes and references

Notes

- these artillery pieces remained at the fort until they were melted by general José María Orellana in 1923 to make one cent Quetzal coins.

References

- Urrutia 2011.

- Almanelly Ruano 2011.

- González Davison 2008, p. 4-15.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 202.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 203.

- Wilhelm of Sweden 1922, p. 192.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 193.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 194.

- Wilhelm of Sweden 1922, p. 194.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 197.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 196.

Bibliography

- Almanelly Ruano (2011). "Historia del Fuerte de San José". Blog de Almanelly Ruano (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- González Davison, Fernando (2008). La montaña infinita; Carrera, caudillo de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Artemis & Edinter. ISBN 84-89452-81-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Móbil, José Antonio (2010). La Década Revolucionaria 1944-1954 (in Spanish). Guatemala: Serviprensa Centroamericana. ISBN 978-9929-554-42-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prins Wilhelm (1922). Between two continents, notes from a journey in Central America, 1920. London, UK: E. Nash and Grayson, Ltd. pp. 148–209.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Urrutia, César (2011). "Historia de la Guatemala City: San José Castle". Guatemala de Ayer (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()