Pedro de Aycinena y Piñol

Pedro de Aycinena y Piñol (19 October 1802 – 14 May 1897[1]) was a conservative politician and member of the Aycinena clan that worked closely with the conservative regime of Rafael Carrera. He was interim president of Guatemala in 1865 after the death of president for life, general Rafael Carrera.

Pedro de Aycinena y Piñol | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th President of Guatemala | |

| In office 14 April 1865 – 24 May 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Rafael Carrera y Turcios |

| Succeeded by | Vicente Cerna y Cerna |

| Secretary of Foreign Affairs of Guatemala | |

| In office 1851 – 14 April 1865 | |

| President | Rafael Carrera |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 October 1802 |

| Died | 14 March 1897 (aged 94) Guatemala City, Guatemala[1] |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Occupation | politician, diplomat |

| Signature |  |

Biography

Aycinena y Piñol was the son of Vicente Aycinena, the second marquis of Aycinena, and was the younger brother of cleric Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol, who inherited the title. Pedro's uncle was Mariano de Aycinena y Piñol, also prominent member of the powerful family. Pedro married his first cousin, Dolores de Aycinena y Micheo, the daughter of a prominent member of the government of Ferdinand VII. Pedro served as Guatemalan minister of foreign relations (1854-71) and therefore played a major role in its foreign policy.[2]

Concordat of 1854

| Concordat between the Holy See and the President of the Republic of Guatemala | |

|---|---|

Captain General Rafael Carrera President of Guatemala in 1854 | |

| Created | 1852 |

| Ratified | 1854 |

| Location | |

| Author(s) | Fernando Lorenzana and Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol |

In 1854 a Concordat was established with the Holy See, which was signed in 1852 by Cardinal Antonelli, Secretary of State of the Vatican and Fernando Lorenzana plenipotentiary -Guatemala Ambassador before the Holy See. Through this treaty -which was designed by Aycinena clan leader, Dr. and clergyman Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol [3] - Guatemala placed its people education under the control of Catholic Church regular orders, committed itself to respect Church property and monasteries, authorized mandatory tithing and allowed the bishops to censor whatever was published in the country; in return, Guatemala received blessings for members of the army, allowed those who had acquired the properties that the Liberals had expropriated the Church in 1829 to keep them, perceived taxes generated by the properties of the Church, and had the right, under Guatemalan law, to judge ecclesiastics who perpetrated certain crimes.[4] The concordat was ratified by Pedro de Aycinena and Rafael Carrera in 1854 and kept a close relationship between Church and State in the country; it was in force until the fall of the conservative government of Marshal Vicente Cerna y Cerna.[4]

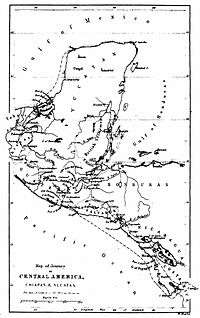

Wyke-Aycinena treaty: Limits convention about Belize

| Wyke-Aycinena treaty | |

|---|---|

| Created | April 30, 1859 |

| Ratified | September 26, 1859 |

| Location | |

| Author(s) | Pedro de Aycinena y Piñol |

| Purpose | Define the borders between the British settlement of Belize and Guatemala.[5] |

The Belize region in the Yucatan peninsula was never occupied by either Spain or Guatemala, even though Spain made some exploratory expeditions in the 16th century that served as its basis to claim the area;[6] Guatemala simply inherited that argument to claim the territory, even though it never sent any expedition to the area after the Independence from Spain in 1821, due to the Central American civil war that ensued and lasted until 1860.[6] On the other hand, the British had established a small settlement there since the middle of the 17th century, mainly as buccaneers quarters and then for fine wood production; the settlements were never recognized as British colonies even though they were somewhat under the jurisdiction of the Jamaican British government.[6] In the 18th century, Belize became the main smuggling center for Central America, even though the British accepted Spanish sovereignty over the region by means of the 1783 and 1786 treaties, in exchange for a cease fire and the authorization for the Englishmen to continue logging in Belize.[6]

After the Central America independence from Spain in 1821, Belize became the leading edge of the commercial entrance of Britain in the isthmus; British commercial brokers established themselves there and created prosperous commercial routes with the Caribbean harbors of Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.[6]

The liberals came to power in Guatemala in 1829 after defeating and expelling the Aycinena family and the regular clergy from the Catholic church, and began a formal complaint before the English crown about the Belize area;[7] at the same time, the liberal caudillo Francisco Morazán, then president of the Central American Federation, had personal dealings with British interests, especially on the fine wood market. In Guatemala, liberal governor Mariano Gálvez made several land concessions to British citizens, among them the best farmland in the country, Hacienda de San Jerónimo in Verapaz; these dealings with Englishmen were used by the secular clergy in Guatemala – who had not been expelled as the monasteries, but had lost the revenue from mandatory tithing which had left it weakened – to accuse the liberal government of heresy and to start a peasant revolt against the heretic liberals and in favor of the "true religion".[8] When Rafael Carrera, peasant revolt leader and commander, came to power in 1840, he stopped the complaints over Belize, and established a Guatemalan consulate in the region to oversee the Guatemalan interests in that important commercial location.[6] Belize commerce was booming in the region until 1855, when the Colombians built a transoceanic railway, which allowed commerce to flow more efficiently to the port at the Pacific; from then on, Belize's commercial importance began a steep decline.[6]

When the Caste War of Yucatán began in 1847 in the Yucatan peninsula – a Maya uprising that resulted in thousands of murdered European settlers – the representatives of Belize and Guatemala were on high alert; Yucatan refugees fled into both Guatemala and Belize and even the Belize superintendent came to fear that Carrera – given his strong alliance with Guatemalan natives – could support the native uprisings in Central America.[6] In the 1850s, the British showed their good will to settle the territorial differences with the Central American countries: they withdrew from the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua and began talks that would end up in the restoration of the territory to Nicaragua in 1894: returned the Bay Islands to Honduras and even negotiated with the American filibuster William Walker in an effort to avoid the invasion of Honduras.[9] They also signed a treaty with Guatemala about its border with Belize, which has been called by Guatemalans the worst mistake made by the conservative regime of Rafael Carrera.[9]

Aycinena y Piñol, as Foreign Secretary, had made an extra effort to keep good relations with the British crown. In 1859, William Walker's threat loomed again over Central America; in order to get the weapons needed to face the filibuster, Carrera's regime had to come to terms about Belize with the British Empire. On 30 April 1859, the Wyke-Aycinena treaty was signed between the English and Guatemalan representatives.[10] The controversial Wyke-Aycinena from 1859 had two parts:

- The first six articles clearly defined the Guatemala-Belize border: Guatemala acknowledged England sovereignty over the Belize territory.[9]

- The seventh article was about the construction of a road between Belize City and Guatemala City, which would be of mutual benefit, as Belize needed a way to communicate with the Pacific coast of Guatemala, having lost its commercial relevance after the construction of the transoceanic railroad in Panama in 1855; on the other hand, Guatemala needed a road to improve communication with its Atlantic coast. However, the road was never built; first because Guatemalan and Belizeans could not reach an agreement of the exact location for the road, and later because the conservatives lost power in Guatemala in 1871, and the liberal government declared the treaty void.[5]

Among those who signed the treaty was José Milla y Vidaurre, who worked with Aycinena in the Foreign Ministry.[11] Rafael Carrera ratified the treaty on 1 May 1859, while Charles Lennox Wyke, British consul in Guatemala, traveled to Great Britain and received the royal approval on 26 September 1859.[5] There were some protests coming from the U.S. consul, Beverly Clarke, and some liberal representatives, but the issue was settled.[5]

References

- Aquiguatemala.net

- Richmond F. Brown, "Pedro de Aycinena" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, pp. 247-48. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- González Davison 2008.

- Aycinena 1854, p. 2-16.

- Woodward 1993, p. 310.

- Woodward 1993, p. 308.

- Woodward 1993.

- González Davison 2008, p. 15-52.

- Woodward 1993, p. 309.

- Hernández de León & 30 abril 1959.

- Hernández de León 1930.

Bibliography

- Aycinena, Pedro de (1854). Concordato entre la Santa Sede y el presidente de la República de Guatemala (in Latin and Spanish). Guatemala: Imprenta La Paz.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- González Davison, Fernando (2008). La montaña infinita; Carrera, caudillo de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Artemis y Edinter. ISBN 84-89452-81-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hernández de León, Federico (1930). El libro de las efemérides (in Spanish). Tomo III. Guatemala: Tipografía Sánchez y de Guise.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1988). Racismo y Análisis Histórico de la Definición del Indio Guatemalteco (in Spanish). Guatemala: Editorial Universitaria.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1990). La patria del criollo; ensayo de interpretación de la realidad colonial guatemalteca (in Spanish). México: Ediciones en Marcha.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodward, Ralph Lee, Jr. (2002). "Rafael Carrera y la creación de la República de Guatemala, 1821–1871". Serie monográfica (in Spanish). CIRMA and Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies (12). ISBN 0-910443-19-X. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2015-01-20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodward, Ralph Lee, Jr. (1993). Rafael Carrera and the Emergence of the Republic of Guatemala, 1821-1871 (Online edition). Athens, Georgia USA: University of Georgia Press. Retrieved December 28, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Pedro de Aycinena (1865)". DeGuate. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

Notes

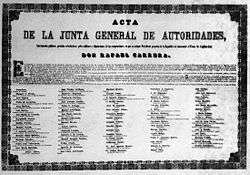

- Aycinena's signature is the fourth from the top down in the first column, left to right

| Preceded by Rafael Carrera |

President of Guatemala 1865 |

Succeeded by Vicente Cerna |

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Tupou I |

Oldest living state leader 18 February 1897 – 14 May 1897 |

Succeeded by Tomás Gomensoro Albín |