Irish Newfoundlanders

In modern Newfoundland (Irish: Talamh an Éisc), many Newfoundlanders are of Irish descent. According to the Statistics Canada 2006 census, 21.5% of Newfoundlanders claim Irish ancestry (other major groups in the province include 43.2% English, 7% Scottish, and 6.1% French).[1] The family names, the features and colouring, the predominance of Catholics in some areas (particularly on the southeast portion of the Avalon Peninsula), the prevalence of Irish music, even the accents of the people in these areas, are so reminiscent of rural Ireland that Irish author Tim Pat Coogan has described Newfoundland as "the most Irish place in the world outside of Ireland",[2].[3][4] Newfoundland has been called "the other Ireland" on a local radio talk show.[5]

History

The large Irish Catholic element in Newfoundland in the 19th century played a major role in Newfoundland history, and developed a strong local culture of their own.[6] They were in repeated political conflict—sometimes violent—with the Protestant Scots-Irish "Orange" element.[7]

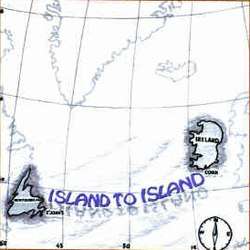

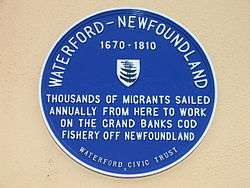

The Irish migrations to Newfoundland, and the associated provisions trade, represent the oldest and most enduring connections between Ireland and North America. As early as 1536, the ship Mighel (Michael) of Kinsale is recorded returning to her home port in County Cork with consignments of Newfoundland fish and cod liver oil. A further hint of what one scholar has termed a diaspora of Irish fishermen dates from 1608, when Patrick Brannock, a Waterford mariner, was reported to sail yearly to Newfoundland. Beginning around 1670, and particularly between 1750 and 1830, Newfoundland received large numbers of Irish immigrants.

These migrations were seasonal or temporary. Most Irish migrants were young men working on contract for English merchants and planters. It was a substantial migration, peaking in the 1770s and 1780s when more than 100 ships and 5,000 men cleared Irish ports for the fishery. The exodus from Ulster to the United States excepted, it was the most substantial movement of Irish across the Atlantic in the 18th century. Some went on to other North American destinations, some stayed, and many engaged in what has been called "to-ing and fro-ing", an annual seasonal migration between Ireland and Newfoundland due to fisheries and trade. As a result, the Newfoundland Irish remained in constant contact with news, politics, and cultural movements back in Ireland.

Virtually from its inception, a small number of young Irish women joined the migration. They tended to stay and marry overwintering Irish male migrants. Seasonal and temporary migrations slowly evolved into emigration and the formation of permanent Irish family settlement in Newfoundland. This pattern intensified with the collapse of the old migratory cod fishery after 1790. An increase in Irish immigration, particularly of women, between 1800 and 1835, and the related natural population growth, helped transform the social, demographic, and cultural character of Newfoundland.

In 1836, the government in St. John's commissioned a census that exceeded in its detail anything recorded to that time. More than 400 settlements were listed. The Irish, and their offspring, composed half of the total population.[8] Close to three-quarters of them lived in St. John's and its near hinterland, from Renews to Carbonear, an area still known as the Irish Shore. There were more Catholic Irish concentrated in this relatively restricted stretch of shore than in any comparable location in Canada.

Location

The vast majority of Irish in Newfoundland arrived from the counties of Wexford, Carlow, Kilkenny, Tipperary, Waterford, Dingle, in Kerry, and Cork. No other provinces in Canada or U.S. state drew such an overwhelming proportion of their immigrants from so geographically compact an area in Ireland over so prolonged a period of time.

Waterford city was the primary port of embarkation. Most migrants came from within a day's journey to the city, or its outport at Passage, 10 km (6 mi) down river in Waterford Harbour. They were drawn from parishes and towns along the main routes of transport and communication, both river and road, converging on Waterford and Passage. New Ross and Youghal were secondary centres of transatlantic embarkation. Old river ports such as Carrick on Suir and Clonmel on the River Suir, Inistioge and Thomastown on the River Nore, and Graiguenamanagh on the River Barrow were important centers of recruitment. So were the rural parishes along these navigable waterways.

Probably the principal motivation for migration was economic distress in the homeland. The population almost doubled between 1785 and 1835, the main period of emigration. Land scarcity, unemployment, underemployment, and the promise of higher wages attracted young Irish women and men to Newfoundland. Irrespective of economic or social origins, almost all Irish moved primarily to better their economic lot.

Language and culture

Most Irish emigrants arrived between 1750 and 1830 from strongly Irish-speaking counties, chiefly in Munster. For the decennial period 1771-1781 the number of Irish speakers in a number of those counties can be estimated as follows: County Kilkenny 57%, County Tipperary 51%, County Waterford 86%, County Kerry 93% and County Cork 84%.[9] Newfoundland is one of the few places outside Ireland where the Irish language was spoken by much of the population as their primary language. It is also the only place outside Europe with its own distinctive name in the Irish language, Talamh an Éisc (Land of the Fish). The Irish language (in its local Munster-derived form) influenced the distinctive varieties of Newfoundland English.

The form of the Irish language known as Newfoundland Irish was associated with an inherited culture of stories, poetry, folklore, traditional feast days, hurling and faction fighting, and flourished for a time in a series of local enclaves. Irish-speaking interpreters were occasionally needed in the courts.[10] Native speakers are likely to have existed even after the First World War.[11]

To Newfoundland the Irish brought family names of southeast Ireland: Wade, McCarthy, O'Rourke, Walsh, Nash,[12] Houlihan, Connors, Hogan, Shea, Stamp, Maher, O'Reilly, Keough, Power, Murphy, Ryan, Griffin, Whelan, O'Brien, Kelly, Hanlon, Neville, Bambrick, Halley, Dillon, Byrne, Lake and FitzGerald. The many Newfoundlanders with the surname Crockwell (Ó Creachmhaoil) derive from 19th Century immigrants from County Galway, in the west of Ireland. Many of the island's more prominent landmarks having already been named by early French and English explorers, but Irish placenames include Ballyhack (Baile Hac), Cappahayden (Ceapach Éidín), Kilbride and St. Bride's (Cill Bhríde), Duntara, Port Kirwan and Skibbereen (Scibirín).

Elements of material culture, agricultural folkways, vernacular and ecclesiastical architecture endured, and trace elements remain. But the commercial cod fishery and the presence of so many English produced a new, composite culture, that of modern Newfoundlanders, a culture unique in modern North America.

Despite the Irish elements in the culture of modern Newfoundland, little attention has been given to the (now moribund) local variety of the Irish language. An exception was the work of the local scholar Aloysius (Aly) O’Brien, who died in 2008.[11]

Tuition in Irish (of a kind not specific to Newfoundland) is available at Memorial University of Newfoundland, which every year appoints an Irish language instructor from abroad.[13]

Religion

Religious faith had great institutional importance. Several of the leading Irish merchants and propertied men were Protestants and brought the traditions of the Orange Order to their new home. But the majority of the Irish were Roman Catholics, and they brought with them a version of Catholicism which was strongly marked by belief in fairies, magic, omens, charms and protective rituals. This tended to reduce their dependence on the Church, which seemed to have no monopoly on the supernatural.[14] Over time, however, the Church managed to impose its discipline in Newfoundland as it had in Ireland, and it became the single most important ethnic, social and cultural institution for the Catholic Irish in Newfoundland. Its clergy and leaders were the de facto leaders of the Irish community.

With Irish being the language of the majority in the early period, it was often the language of church services.[15] The Catholic Bishop James Louis O'Donel, when requesting a Franciscan missionary for the parishes of St. Mary's and Trepassey, said that such a missionary would need to be fluent in Irish (like O'Donel himself).[16] It also played a part in the greatest early challenge to the Catholic Church, when the Reverend Laurence Coughlan, a Methodist preacher, managed to convert most of the Newfoundland North Shore in the 1760s largely because of his fluency in Irish.[16]

Irish Catholic religious orders

As the permanent population, and the numbers of young people and children in Newfoundland increased during the early 19th century, public interest in access to education also grew. Bishop Michael Anthony Fleming was aware of this and of the religious opportunities that it presented. He wanted "cradle-to-grave" cultural institutions for Irish Roman Catholics and, in particular, wanted to address the needs and aspirations of working class Catholics. He therefore recruited religious orders of women from Ireland.

In March 1833, Bishop Fleming went to Galway, Ireland, where he sought several sisters of the order of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary to open a school for female children in Newfoundland. In 1839 he also invited the Sisters of Mercy. The work of the two orders was the basis of Catholic and inter-denominational education for the next century and a half. Over the next century parents of all denominations sent children to be educated in their convents.

In 1847 Bishop Fleming recruited four brothers of the Third Order of Saint Francis from the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tuam, Ireland, to teach at the Benevolent Irish Society's school.

Building a cathedral

The rapid growth of the Irish population in St. John's during the early years of the 19th century that the Catholic chapel had to be repeatedly enlarged. By the mid-1830s the Old Chapel had long outlived its usefulness and Bishop Fleming wanted a more commodious church. He and his successor, Bishop John T. Mullock, supervised the construction. The Basilica of St. John the Baptist was built between 1839-1855 of stone imported from Ireland and was one of the largest Cathedrals in North America at the time of its construction.

Rebellion

In 1800, a cell of the Society of United Irishmen was uncovered in the St. John's Garrison and planned to rebel against the English authority in the United Irish Uprising, making Newfoundland one of the few places outside Ireland in which the Irish Rebellion of 1798 had political effects.

Even at the time of the Napoleonic Wars, political activism rooted in Irish agrarian movements manifested themselves in Newfoundland, in such forms such as the Caravats (Irish: Carabhataí), who wore French cravates (ties) and the Shanavests (Irish: Seanabheastaí, Seanabheisteanna "Old Vests").

Benevolent Irish Society

In the early years of the 19th century St. John's had a large Irish population with some members of affluence. It was a town with growing influence, and was the cradle of growing cultural and political ferment. Members of the local Irish middle class saw social needs unmet by government and also wanted to belong to a fraternal, gentlemanly organization. In 1806, under Bishop O'Donel's patronage, they founded the Benevolent Irish Society (the BIS) as a charitable, non-profit, non-sectarian society for Irish-born men under the motto "He who gives to the poor lends to the Lord". In 1823 the BIS collected a subscription and opened a non-sectarian school, the Orphan Asylum, in St. John's, for the education of the poor.

Irish fraternities

Outside the Benevolent Irish Society (BIS), there were two fraternal organizations to which Irish Catholics in Newfoundland belonged. The earliest to be established in Newfoundland was the Irish Mechanics' Society, organized in March 1827. The Mechanics' Society was established as a self-help and educational society by four skilled tradesmen, Patrick Kelly, Edmond Power, Louis Martin, and William Walsh. The Society provided a meeting place and educational opportunities for its members, a sickness insurance scheme, and a program of benefits for injured members or the families of deceased members. Many of the early members of the Mechanics' Society were Irish Catholics from St. John's, but intra-Irish county origins, and membership in Irish provincial factions the Tipperary Clear Airs, the Wexford Yellowbellies, the Waterford Wheybellies, the Kilkenny Doones, and the Cork Dadyeens may also have played a part in determining its membership. Like the Benevolent Irish Society, the rules of the Mechanics' Society prohibited members from formally discussing political or religious questions, but the Society occasionally took a public political stand. In 1829 it participated in a large parade through St. John's to celebrate the Catholic emancipation. Many of its early leaders became prominent in political life.

The Irish temperance movement was founded in Cork, Ireland in April 1838 by the Franciscan priest, Father Theobald Mathew. In 1841 the movement was introduced to St. John's by Father Kyran Walsh. During the 1840s and into the 1860s, the Newfoundland Temperance Society became one of the most popular working class fraternal organizations in St. John's. In the context of Irish culture and politics, the Irish temperance movement in Newfoundland also became a political forum for lobbying for the repeal of the Acts of Union 1800 that united Ireland with the Kingdom of Great Britain, particularly during the Repeal Year of 1843. By 1844, over 10,000 members had enrolled and by the late 19th century, the society developed a substantial membership and social presence in St. John's. In the early 20th century, the society became renowned for its literary and musical events, and remained one of the most active and influential fraternal societies in St. John's until the 1990s.

See also

- Benevolent Irish Society

- United Irish Uprising

- Newfoundland Irish

- Irish diaspora

- Newfoundland (island)

- Dominion of Newfoundland

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- Thomas Nash (Newfoundland) Irish fisherman, settled in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Founder of Branch, Newfoundland and Labrador[17]

References

- "2006 Statistics Canada National Census: Newfoundland and Labrador". Statistics Canada. 2009-07-28. Archived from the original on 2011-01-15.

- Tim Pat Coogan, Wherever Green Is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002

- https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/1916-the-mornings-after-review-tim-pat-coogan-s-arrogant-travesty-of-irish-history-1.2438119

- Tim Pat Coogan#Criticism

- Johanne Devlin Trew, "The Forgotten Irish? Contested sites and narratives of nation in Newfoundland." Ethnologies 27#2 (2005): 43-77.

- John Edward FitzGerald, Conflict and culture in Irish-Newfoundland Roman Catholicism, 1829-1850 (University of Ottawa, 1997.)

- John Mannion, PNLA Exhibit, 1996 as cited in National Adult Literacy Database guidebook on Newfoundland multiculturalism Archived 2008-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- See Fitzgerald 1984.

- Kirwan 1993, p. 68.

- ‘Aloysius O’Brien, 93: Agronomist,’ J.M. O’Sullivan, 13 October 2008, The Globe and Mail.

- "RootsWeb.com Home Page". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Teagascóirí Gaeilge - Ireland Canada University Foundation". Icuf.ie. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Connolly 1982, p. 119-120.

- O’Grady 2004, p. 56

- Newfoundland: The Most Irish Place Outside of Ireland, Brian McGinn, the Irish Diaspora Studies scholarly network

- "Historic Places". Historicplaces.ca. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

Further reading

- Casey, George. "Irish culture in Newfoundland." in Cyril J. Byrne and Margaret R. Harry eds., Talamh an eisc: Canadian and Irish essays (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing. 1986) pp: 203-227.

- Connolly, S.J. (1982). Priests and People in Pre-Famine Ireland 1780-1845. Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-64411-6.

- Fitzgerald, Garrett, ‘Estimates for baronies of minimal level of Irish-speaking amongst successive decennial cohorts, 117-1781 to 1861-1871,’ Volume 84, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 1984.

- FitzGerald, John Edward. "Conflict and Culture in Irish-Newfoundland Roman Catholicism, 1829-1850." (Ph.D. dissertation, 1997. University of Ottawa) Abstract

- Kirwan, William J. (1993). ‘The planting of Anglo-Irish in Newfoundland’ in Focus on Canada, Sandra Clark (ed.). John Benjamin's Publishing Company. ISBN 90-272-4869-9

- O’Grady, Brendan (2004). Exiles and Islanders: The Irish Settlers of Prince Edward Island. MQUP.

- Trew, Johanne Devlin Trew, "The Forgotten Irish? Contested sites and narratives of nation in Newfoundland." Ethnologies 27#2 (2005): 43-77. online

- Ó hEadhra, Aogán (1998). Na Gaeil i dTalamh an Éisc. Coiscéim.

External links

- Statistics Canada: 2006 Population by selected ethnicity, Newfoundland and Labrador

- Newfoundland: The Most Irish Place Outside of Ireland

- The Irish Loop on the southern portion of Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula

- Statistics Canada 2006 Census - Ethnic Origin by Sex, Newfoundland and Labrador

- Newfoundland's Grand Banks site - Genealogical and Historical Data for the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador

- National Adult Literacy Database guidebook on Newfoundland multiculturalism