Irish National Liberation Army

The Irish National Liberation Army (INLA, Irish: Arm Saoirse Náisiúnta na hÉireann)[5] is an Irish republican communist paramilitary group formed on 10 December 1974, during "the Troubles". It seeks to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a socialist republic encompassing all of Ireland. It is the paramilitary wing of the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP).

| |

|---|---|

| Participant in the Troubles | |

The INLA logo consisting of the Starry Plough and the Flag of Ireland with a red star and a fist holding an AK-47-derivative rifle. | |

| Active | December 1974 – present (on ceasefire since 1998, formally ended armed campaign in 2009)[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Leaders | |

| Headquarters | Dublin |

| Area of operations | |

| Size | Unknown, at least 80 members at first meeting in December 1974, the Derry Brigade had over 150 volunteers by the end of 1975 and over 1,000 volunteers were arrested during The Troubles between 1975 – 1994 [2] |

| Allies | Other Marxist Guerrilla organizations in Europe like Catalan Liberation Front and Action directe [3][4] |

| Opponent(s) | United Kingdom Republic of Ireland Loyalist paramilitaries |

| Battles and war(s) | Central Bar bombing 1975 Airey Neave killing 1979 Divis Flats bombing 1982 Ballykelly bombing 1982 Darkley Killings 1983 Rossnaree shooting 1987 Springhill Avenue shooting 1987 1994 Shankill Road Killings July 1997 riots Newtownhamilton bombing 1998 |

The INLA was founded by former members of the Official Irish Republican Army who opposed that group's ceasefire. It was initially known as the "People's Liberation Army" or "People's Republican Army". The INLA waged a paramilitary campaign against the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in Northern Ireland. It was also active to a lesser extent in the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain. High-profile attacks carried out by the INLA include the Droppin Well bombing, the 1994 Shankill Road killings and the assassinations of Airey Neave in 1979 and Billy Wright in 1997. However, it was smaller and less active than the main republican paramilitary group, the Provisional IRA. It was also weakened by feuds and internal tensions. Members of the group used the covernames People's Liberation Army (PLA), People's Republican Army (PRA)[6] and Catholic Reaction Force (CRF)[7] for attacks its volunteers carried out but the INLA did not want to claim responsibility for.[8] The INLA became a proscribed group in the United Kingdom on 3 July 1979 under the 1974 Prevention of Terrorism Act.[9]

After a 24-year armed campaign, the INLA declared a ceasefire on 22 August 1998.[10] In August 1999, it stated that "There is no political or moral argument to justify a resumption of the campaign".[11] In October 2009, the INLA formally vowed to pursue its aims through peaceful political means[1] and began decommissioning its weapons.

The party supports a "No First Strike" policy, that is allowing people to see the perceived failure of the peace process for themselves without military actions.[12]

The INLA is a Proscribed Organisation in the United Kingdom under the Terrorism Act 2000 and an illegal organisation in the Republic of Ireland.[13][14]

History

Foundation

The INLA was founded on 8 December 1974 in the Spa Hotel in Lucan, Dublin, by former members of the Official IRA. The group's political wing, the IRSP was founded on the same day. The IRSP's foundation was made public but the INLA's was kept a secret until the group could operate effectively. The group was formed due to dissatisfaction with the Official IRA ceasefire in 1972 and the supposed refusal to implement the democratic will of the members.[15] Shortly after it was founded, the INLA came under attack from their former comrades in the OIRA, who wanted to destroy the new grouping before it could get off the ground.

On 20 February 1975, Hugh Ferguson, an INLA member and an Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) branch chairperson, was the first person to be killed in the feud. One of the first military operations of the INLA was the shooting of OIRA leader Sean Garland in Dublin on 1 March. Although shot six times, he survived. After several more shootings a truce was arranged, but fighting started again. The most prominent victim of the restarted feud was Billy McMillen, the commander of the OIRA in Belfast, shot by INLA member Gerard Steenson.[16] His murder was unauthorised and was condemned by Costello.[17] This was followed by several more assassinations on both sides, the most prominent victim being Seamus Costello, who was shot dead on the North Strand Road in Dublin on 5 October 1977. Costello's death was a severe blow to the INLA, as he was their most able political and military leader.

It has been claimed by some in the Republican Socialist Movement that one of their members killed in 1975, Brendan McNamee (who was involved in the killing of Billy McMillen), was actually killed by Provisional Irish Republican Army members. The Officials had denied involvement at the time of the killing and had instead blamed it on the Provisionals, who also denied involvement.[18]

Armed campaign

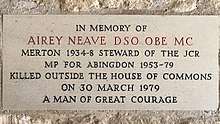

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the INLA developed into a modest organisation in Northern Ireland, operating primarily from the Divis Flats in west Belfast, which, as a result, became colloquially known as "the planet of the Irps" (a reference to the IRSP and the film Planet of the Apes).[19] They also had a large presence in Derry and the surrounding area, and all three of the INLA prisoners who died in the 1981 Irish hunger strike were from County Londonderry. During this period, the INLA competed with the Provisional IRA for members, with both groups in conflict with the British Army and the Royal Ulster Constabulary. The first action to bring the INLA to international notice was its assassination on 30 March 1979 of Airey Neave, the British Conservative Party's spokesman on Northern Ireland and one of Margaret Thatcher's closest political supporters.

The INLA lost another of its founding leadership in 1980, when Ronnie Bunting, a Protestant nationalist, was assassinated at his home.[20] Noel Little, another Protestant member of the INLA, was killed in the same incident. The Ulster Defence Association, an Ulster Loyalist paramilitary, claimed responsibility for both killings. Another leading INLA member,[21] Miriam Daly, was killed by Loyalist assassins in the same year. Although no group claimed responsibility, the INLA claimed that the Special Air Service (SAS) was involved in the killings of Bunting and Little.[22] Offensive INLA actions at this time included the 1982 bombing of the Mount Gabriel radar station in County Cork, which the INLA believed was providing assistance to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in violation of Irish neutrality, although this was disputed by the Irish government.[23] Their most bloody attack came on 6 December 1982 – the Ballykelly disco bombing of the Droppin' Well Bar in Ballykelly, County Londonderry, which catered to British military personnel, in which 11 soldiers on leave and 6 civilians were killed.

Members of the INLA participated in the 1980 and 1981 hunger strikes for the recognition of the political status of paramilitary prisoners. Three INLA members died during the latter hunger strike – Patsy O'Hara, Kevin Lynch, and Michael Devine, along with seven Provisional IRA members.

On 20 November 1983, three members of the congregation in the Mountain Lodge Pentecostal Church, Darkley, (near Keady, County Armagh) were shot dead during a Sunday service. The attack was claimed by the Catholic Reaction Force, a cover name for a small group of people, including one member of the INLA. The weapon used came from an INLA arms dump, but Tim Pat Coogan claims in his book The IRA that the weapon had been given to the INLA member to assassinate a known loyalist and the attack on the church was not sanctioned. The INLA's then-chief of staff, Dominic McGlinchey, came out of hiding to condemn the attack. In 1987 the INLA came under attack from the Irish People's Liberation Organisation (IPLO), a group made up of expelled or disaffected members of the INLA. This feud resulted in the death of 16 INLA and IPLO members. The feud mainly took place in cities, most notably in Belfast, Derry, and Dublin, but also took place in many other areas of Ireland. The feud ended in 1992 with the INLA surviving just barely, with the Provisional IRA stepping in and wiping out the main Belfast leadership of the IPLO because they were openly involved in drug dealing, while letting the rest of the organization dissolve outside of Belfast.

On 14 April 1992, the INLA carried out its first killing in England after the death of Airey Neave, when they shot dead a recruiting army sergeant in Derby while he was leaving a British Army recruiting office.[24] In June 2010, Declan Duffy was charged with the killing,[25] although he was released in March 2013, under the terms of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.[26]

INLA gunmen opened fire on British soldiers in the Ardoyne area of North Belfast on 7 July 1997, when the Drumcree conflict triggered six days of fierce riots and widespread violence in several nationalist areas of Northern Ireland.[27]

Supergrass

In the mid-1980s, the INLA was greatly weakened by splits and criminality within its own ranks, as well as the conviction of many of its members under the supergrass scheme. Harry Kirkpatrick, an INLA volunteer, was arrested in February 1983 on charges of five murders and subsequently agreed to give evidence against other INLA members.[28]

The INLA kidnapped Kirkpatrick's wife Elizabeth,[29] and later kidnapped his sister and his stepfather too. All were released physically unharmed. INLA Chief of Staff Dominic McGlinchey is alleged to have killed Kirkpatrick's lifelong friend Gerard 'Sparky' Barkley because he may have revealed the whereabouts of the Kirkpatrick family members to the police.[30]

In May 1983, ten men were charged with various offences on the basis of evidence from Kirkpatrick. Those charged included IRSP vice-chairman Kevin McQuillan and former councillor Sean Flynn. IRSP chairman and INLA member James Brown was charged with the murder of a police officer.[31] Others escaped; Jim Barr, an IRSP member named by Kirkpatrick as part of the INLA, fled to the US where, having spent 17 months in jail, he won political asylum in 1993.[32][33]

In December 1985, 27 people were convicted on the basis of Kirkpatrick's statements. By December 1986, 24 of those convictions had been overturned. Gerard Steenson was given five life sentences for the deaths of the same five individuals that Kirkpatrick himself had been convicted of, these included Ulster Defence Regiment soldier Colin Quinn, shot in Belfast in December 1980.

The distrust and division that had been sowed was the last straw in splitting former comrades into warring factions and leading to the formation of the Irish People's Liberation Organisation by Jimmy Brown and Gerard Steenson, both of whom had been convicted under the supergrass scheme. This led to that organisation's feud with the INLA, in which 16 people were killed.

Killing of Seamus Ruddy

Seamus Ruddy from Newry joined the INLA in Dublin in the 1970s. He was arrested in 1978 for smuggling arms but was acquitted. After dissension among local members, Ruddy drifted away from the main organisation and in 1983 went to Paris where he taught English. He disappeared in late May 1985, after a meeting with three leading members of the INLA. The three were searching for arms and believed that Ruddy knew where they could be found. At the time, the INLA denied that it was involved with his disappearance and resisted pressure from the Ruddy family to help it locate his whereabouts. In late 1993, a former high-ranking member of the INLA, Peter Stewart, finally admitted that the INLA had killed Ruddy in Paris. Ruddy's remains were found there in 2017.[34]

Feuds and splits

In 1987, the INLA and its political wing, the IRSP came under attack from the Irish People's Liberation Organisation (IPLO), an organisation founded by people who had resigned or been expelled from the INLA. The IPLO's initial aim was to destroy the INLA and replace it with their organisation. Five members of the INLA were killed by the IPLO, including leaders Ta Power and John O'Reilly. The INLA retaliated with several killings of their own. After the INLA killed the IPLO's leader, Gerard Steenson in 1987, a truce was reached. Although severely damaged by the IPLO's attacks, the INLA continued to exist. The IPLO, which was heavily involved in drug dealing, was put out of existence by the Provisional IRA in a large scale operation in 1992.

Directly after the feud in October 1987, the INLA received more damaging publicity when Dessie O'Hare, an erstwhile INLA volunteer, set up his own group called the "Irish Revolutionary Brigade" and kidnapped a Dublin dentist named John O'Grady. O'Hare cut off two of O'Grady's fingers and sent them to his family in order to secure a ransom. O'Grady was eventually rescued and O'Hare's group arrested after several shootouts with armed Gardaí. The INLA disassociated itself from the action, issuing a statement saying O'Hare "is not a member of the INLA".[35] O'Hare later rejoined the INLA while in prison.

Dominic McGlinchey was killed in 1994 by unknown assailants after being released from prison the previous year.

In 1995, four members of the INLA, including chief of staff Hugh Torney, were arrested by Gardaí in Balbriggan while trying to smuggle weapons from Dublin to Belfast. Torney, with the support of two of his co-accused, called a ceasefire in exchange for favourable treatment by the Irish Government. Since Torney, who was chief of staff, under the INLA's rules lacked the authority to call a ceasefire (because he was incarcerated), he and the two men who supported him were expelled from the INLA.

Torney and one of those men, Dessie McCleery, as well as founder-member John Fennell, did not wish to surrender the leadership of the organisation. Their faction, known as the INLA/GHQ, assassinated the new INLA chief of staff, Gino Gallagher. After the INLA killed both McCleery and Torney in 1996, the rest of Torney's faction quietly disbanded.

Killing of Billy Wright

.jpg)

Billy Wright was the founder and leader of the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF). Since July 1996, the group had launched a string of attacks on civilians (whom they identified as Catholics), killing at least five. In April 1997, Wright was sentenced to eight years in the Maze Prison. On the morning of 27 December 1997, he was assassinated by three INLA prisoners – Christopher "Crip" McWilliams, John "Sonny" Glennon and John Kennaway – who were armed with two pistols.[36] He was shot as he travelled in a prison van (alongside another LVF prisoner, Norman Green and one prison officer) from one part of the prison to another.[36] Kennaway held the driver hostage and Glennon gave cover with a .22 Derringer pistol while McWilliams opened the side door and fired seven shots at Wright with his PA63 semi-automatic.[36][37] After killing Wright, the three volunteers handed themselves over to prison guards.[36][37] They also handed over a statement, which read:

"Billy Wright was executed for one reason and one reason only, and that was for directing and waging his campaign of terror against the nationalist people from his prison cell in Long Kesh.[36]

That night, LVF gunmen opened fire on a disco in a mainly nationalist area of Dungannon. Four civilians were wounded and a former Provisional IRA volunteer was killed in the attack.[38]

The nature of Wright's killing led to speculation that prison authorities colluded with the INLA to have him killed, as he was a danger to the peace process. The INLA strongly denied these rumours, and published a detailed account of the assassination in the March/April 1999 issue of The Starry Plough newspaper.[36]

Ceasefire

The INLA declared a ceasefire on 22 August 1998. When calling its ceasefire, the INLA acknowledged the "faults and grievous errors in our prosecution of the war". The INLA admitted that innocent people had been killed and injured "and at times our actions as a liberation army fell far short of what they should have been". The INLA went on to accept the massive vote in favour of the Good Friday Agreement – which it had opposed during the 1998 referendum – by the people of Ireland. It said "The will of the Irish people is clear. It is now time to silence the guns and allow the working classes the time and the opportunity to advance their demands and their needs."[39]

Although the INLA does not support the Good Friday Agreement, it does not call for a return to armed struggle on behalf of republicans either. An INLA statement released in 1999 declared, "we do not see a return to armed struggle as a viable option at the present time".[40]

Post-ceasefire activities

The INLA maintains a presence in parts of Northern Ireland and has carried out punishment beatings on alleged petty criminals.[41]

The Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC), which monitors paramilitary activity in Northern Ireland, claimed in a November 2004 report that the INLA was heavily involved in criminality. In 1997, an INLA man named John Morris was shot dead by Garda Síochána (the Republic's police force) in Dublin during the attempted robbery of a newspaper distributor's depot in Inchicore. Three other INLA members were arrested in the incident. In 1999, the INLA in Dublin became involved in a feud with a criminal gang in the city.[42][43] After a young INLA man named Patrick Campbell was killed by drug dealers, the INLA carried out several shootings in reprisal, including at least one killing.[43][44] Republic of Ireland journalist Paul Williams has also claimed the INLA, especially in Dublin, is now primarily a front for organised crime. The IRSP and INLA deny these allegations, arguing that no one has been simultaneously convicted of membership in the INLA and of drug offences. The IRSP and the INLA have both strongly denied any involvement with drug dealing, stating that the INLA has threatened criminals which it claims have falsely used its name.

In 2006, the INLA claimed to have put at least two drugs gangs out of business in Northern Ireland. After their raid on a criminal organisation based in the northwest, they released a statement saying that "the Irish National Liberation Army will not allow the working class people of this city to be used as cannon fodder by these criminals whose only concern is profit by whatever means available to them."[45][46]

The October 2006 IMC report stated that the INLA "was not capable of undertaking a sustained campaign [against the United Kingdom], nor does it aspire to".[47]

In December 2007, disturbances broke out at an INLA parade in the Bogside in Derry between spectators and Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) officers attempting to arrest four of the marchers.[48]

In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth IMC reports the INLA was said to remain a threat, with a desire to mount attacks that could well be more dangerous in the future, but was characterized as being largely a criminal enterprise at that time. The INLA killed Brian McGlynn on 3 June 2007 during the span of the first of these reports. This killing was said to have occurred because the victim used the INLA name in the drug trade.[49][50] On 24 June 2008, the INLA was said to have committed the murder of Emmett Shiels, although the IMC report did indicate the investigation was continuing. It was also said to be partaking in "serious crimes" such as drug dealing, extortion, robbery, fuel laundering and smuggling.[51] Furthermore, the INLA and Continuity IRA were stated to have co-operated.

On 15 February 2009 the INLA claimed responsibility for the shooting death of Derry drug dealer Jim McConnell.[52]

In March 2009 it was reported that the INLA had stood down its Dublin Brigade in order to allow its army council to carry out an internal investigation into allegations of drug dealing and criminality. The INLA denied it as an organisation was involved in drug dealing and went on to say that "As a result of evidence presented to us, we are investigating the activities of people associated with us in [Dublin]. Pending that outcome, we have stood down several people."[53] A short time later the INLA's Dublin Commander, Declan "Whacker" Duffy, publicly disassociated himself from the organisation. Duffy criticized the INLA leadership stating that "You would imagine if there was a thorough investigation being carried out by the INLA they would have at least came and spoke to me." He went on to state that: "I can't deny that I’m disappointed with the way the INLA has handled things but at the same time I'm not going to get into a sniping match with them."[54]

On 19 August 2009 the INLA shot and wounded a man in Derry. The INLA claimed that the man was involved in drug dealing although the injured man and his family denied the allegation.[55] However, in a newspaper article on 28 August the victim retracted his previous statement and admitted that he had been involved in small scale drug dealing but has since ceased these activities.[56]

End of armed campaign

On 11 October 2009, speaking at the graveside of its founder Seamus Costello in Bray, the INLA formally announced an end to its armed campaign, stating the current political framework allowed for the pursuit of its goals through peaceful, democratic means.[1][57] Martin McMonagle from Derry said: "The Republican Socialist Movement has been informed by the INLA that following a process of serious debate ... it has concluded that the armed struggle is over. The objective of a 32-county socialist republic will be best achieved through exclusively peaceful political struggle".[58][59][60]

The governments of Britain and Ireland were informed before the announcement.[61] Hillary Clinton of the United States was due to visit Belfast the following day.[61] Sinn Féin's Gerry Adams was doubtful but added: "However, if it is followed by the actions that are necessary, this is a welcome development".[62] On 6 February 2010, days before the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD) was due to disband, the INLA revealed that it had decommissioned its weapons over the preceding few weeks.[63] Had the INLA retained its weapons beyond 9 February, the date on which the legislation under which the IICD operated ended, then they would have been treated as belonging to common criminals rather than remnants from the Troubles.[63]

The decommissioning was confirmed by General John de Chastelain of the IICD on 8 February 2010.[64] On the same day INLA spokesman Martin McMonagle said that the INLA made "no apology for [its] part in the conflict" but they believed in the "primacy of politics" to "advance the working class struggle in Ireland".[64]

Chiefs of staff

| No. | Name | Assumed position | Left position | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seamus Costello | 1974 | 5 October 1977 | [65] |

| 2 | Dominic McGlinchey | 1982 | 1984 | [66] |

| 4 | Hugh Torney | ? | 1990s | [67] |

| 4 | Gino Gallagher | ? | 1996 | [66] |

Deaths as a result of activity

According to Malcolm Sutton's Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland, part of the Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN), the INLA was responsible for at least 120 killings during the Troubles, between 1969 and 2001. This includes those claimed by the "People's Liberation Army" and "People's Republican Army".[68] According to the book Lost Lives (2006 edition), it was responsible for 127 killings.[69]

Of those killed by the INLA:[70]

- 46 (~38%) were members or former members of the British security forces, including:

- 26 British military personnel and 1 former soldier

- 13 Royal Ulster Constabulary officers and 4 former officers

- 2 Northern Ireland Prison Service officers

- 44 (~36%) were civilians – including politicians, alleged informers and alleged criminals

- 20 (~16%) were members or former members of republican paramilitary groups

- 8 (~6%) were members or former members of loyalist paramilitary groups

- 2 were members of the Irish security forces

The CAIN database says there were 39 INLA members killed during the conflict,[71] while Lost Lives says there were 44 killed.[69]

References

- "'Armed struggle is over' – INLA". BBC News. 11 October 2009.

- Jack Holland & Henry McDonald, INLA – Deadly Divisions, 1994, p.6

- Jack Holland & Henry McDonald, INLA – Deadly Divisions, 1994, p.246-8

- Jack Holland & Henry McDonald, INLA – Deadly Divisions, 1994, p.146-7, p.214-15

- INLA memorial (Carlton Court, Strabane), Conflict Archive on the Internet.

- Sutton, Malcolm. "CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1983". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- https://fas.org/irp/world/para/inla.htm

- Ruan O'Donnell – Special Category: The IRA in English Prisons: Vol. 2: 1978–1985 p. 83

- "UK and Ireland welcome INLA ceasefire". BBC News. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "INLA 'declares war is over'". BBC News. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "What is Irish Republican Socialism?". Archived from the original on 30 June 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Terrorism Act 2000". Schedule 2, Act No. 11 of 2000.

- THE OFFENCES AGAINST THE STATE ACTS, 1939–1998

- "Perspectives on the future of Republican Socialism in Ireland" (PDF). irsp.ie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017.

- Holland, Jack; McDonald, Henry (1996). INLA Deadly Divisions. Poolbeg. p. 68. ISBN 1-85371-263-9.

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, Penguin Books, ISBN 1-84488-120-2 pp. 296–297

- Holland, Jack; McDonald, Henry (1996). INLA Deadly Divisions. Poolbeg. pp. 125–26. ISBN 1-85371-263-9.

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, Penguin Books, ISBN 1-84488-120-2 p. 290

- Deadly Divisions, p. 160

- "Unveiling of Memorial for INLA Volunteers Brendan Mc Namee and Miriam Daly". irsm.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- IRSP (November 1980). "Ronnie Bunting and Noel Lyttle". The Starry Plough. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- "Ceisteanna—Questions. Oral Answers. – Shanwick Air Radio". Houses of the Oireachtas. 17 June 1986.

- "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1992". ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "Man charged over 1992 murder of soldier in Derby". BBC News. 30 June 2010.

- Justice system 'totally wrong' to free killer Declan Duffy, says victim's ex-wife by Aly Walsh, Derby Telegraph, 29 March 2013

- "CAIN: Peter Heathwood Collection of Television Programmes – Search Page". ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- Five life terms ...;The Times; 4 June 1983; pg1 col G

- Wife seized by INLA; The Times, 17 May 1983; pg32 col A

- Lost Lives, 2007 edition, ISBN 1-84018-504-X

- 'Ulster Youths throw ...; The Times; 23 May 1983; pg2 col A

- USA v. James Barr: 84-CR-00272

- Greer 1990

- "In France, uncovering North's grisly past". 16 February 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Holland, McDonald, INLA Deadly Divisions, pp.304–305

- The Starry Plough – March/April 1999 Archived 1 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Pages 10–11.

- "1997: Loyalist leader murdered in prison". BBC News. 27 December 1997. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Provos in crisis talks to try to restrain hardliners Archived 1 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Irish News, 29 December 1997

- "Terrorists reach the crossroads". The Guardian. London. 17 October 1999. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "This site is temporarily unavailable". Archived from the original on 6 October 2007.

- "Action Taken Against Ardoyne Thug Necessary – INLA". irsm.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "Gardaí warn that INLA feud could escalate". RTÉ.ie. 11 October 1999. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "Feud death adds one more to body count of 10-year bloodbath". Independent.ie. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "The INLA hasn't gone away either, you know . . ". Independent.ie. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "Blogsome". Archived from the original on 23 February 2007.

- "INLA dismantles another criminal gang". indymedia.ie. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "PremiumSale.com Premium Domains" (PDF). independentmonitoringcommission.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "Police attacked during INLA march". The Irish Times. 9 December 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- "Eighteenth Report of the Independent Monitoring Commission" (PDF). Independent Monitoring Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

- "Eighteenth Report of the Independent Monitoring Commission" (PDF). Independent Monitoring Commission. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Twentieth Report of the Independent Monitoring Commission Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 10 November 2008

- INLA claims responsibility for murder of Derry drug dealer Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 26 May 2009

- "INLA Stand Down Dublin Brigade". News24. 10 March 2009.

- Irish news Internet Service. "headlines – Irish News Online". the irish news. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- INLA say they shot father-of-three Derry Journal – 21 August 2009

- INLA victim tells 'Journal' 'I did deal in drugs – but not anymore' Derry Journal – 28 August 2009

- "Irish National Liberation Army renounces violence in N. Ireland". Xinhua News Agency. 12 October 2009. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- "Irish paramilitary group renounces armed struggle". ABC News (Australia). 12 October 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- Michael O'Regan; Gerry Moriarty (12 October 2009). "INLA 'has ended armed struggle' says statement from organisation". The Irish Times. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- "INLA ends campaign of violence". RTÉ. 11 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Henry McDonald (12 October 2009). "Irish National Liberation Army to disband and give up weapons". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- "Irish National Liberation Army renounces violence". CBC News. 11 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Vincent Kearney (6 February 2010). "Northern Ireland INLA paramilitaries dump terror cache". BBC News. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "PM praises Northern Ireland decommissioning moves". BBC News. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "Notes on Ta Power – Educational Piece 2". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "INLA halt was on cards for months".

- "How a key German mole nearly wrecked the INLA – Independent.ie".

- "Sutton Index of Deaths: Organisation responsible for the death". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- David McKittrick et al. Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Random House, 2006. pp. 1551–54

- "Sutton Index of Deaths: Crosstabulations (two-way tables)". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Retrieved 1 September 2014. (choose "organization" and "status"/"status summary" as the variables)

- "Sutton Index of Deaths: Status of the person killed". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Retrieved 1 September 2014.

Sources

- Jack Holland, Henry McDonald, INLA – Deadly Divisions'

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2

- CAIN project

- Coogan, Tim Pat, The IRA, Fontana Books, ISBN 0-00-636943-X

- The Starry Plough – IRSP newspaper

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irish National Liberation Army. |