Planet of the Apes (1968 film)

Planet of the Apes is a 1968 American science fiction film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner. It stars Charlton Heston, Roddy McDowall, Kim Hunter, Maurice Evans, James Whitmore, James Daly and Linda Harrison. The screenplay by Michael Wilson and Rod Serling was loosely based on the 1963 French novel La Planète des Singes by Pierre Boulle. Jerry Goldsmith composed the groundbreaking avant-garde score. It was the first in a series of five films made between 1968 and 1973, all produced by Arthur P. Jacobs and released by 20th Century Fox.[3]

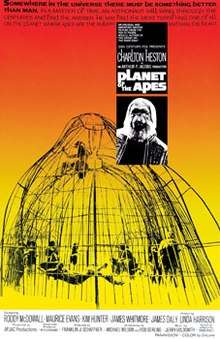

| Planet of the Apes | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Franklin J. Schaffner |

| Produced by | Arthur P. Jacobs |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Planet of the Apes by Pierre Boulle |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

| Cinematography | Leon Shamroy |

| Edited by | Hugh S. Fowler |

Production company | APJAC Productions |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.8 million[2] |

| Box office | $33.4 million (North America)[2] |

The film tells the story of an astronaut crew who crash-lands on a strange planet in the distant future. Although the planet appears desolate at first, the surviving crew members stumble upon a society in which apes have evolved into creatures with human-like intelligence and speech. The apes have assumed the role of the dominant species and humans are mute creatures wearing animal skins.

The script, originally written by Serling, underwent many rewrites before filming eventually began.[4] Directors J. Lee Thompson and Blake Edwards were approached, but the film's producer Arthur P. Jacobs, upon the recommendation of Charlton Heston, chose Franklin J. Schaffner to direct the film. Schaffner's changes included an ape society less advanced—and therefore less expensive to depict—than that of the original novel.[3] Filming took place between May 21 and August 10, 1967, in California, Utah and Arizona, with desert sequences shot in and around Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The film's final "closed" cost was $5.8 million.

The film was released in the United States on February 8, 1968, and was a commercial success, earning a lifetime domestic gross of $32.6 million.[5] The film was groundbreaking for its prosthetic makeup techniques by artist John Chambers[6] and was well received by critics and audiences, launching a film franchise,[7] including four sequels, as well as a short-lived television show, animated series, comic books, and various merchandising. In particular, Roddy McDowall had a long-running relationship with the Apes series, appearing in four of the original five films (absent, from the second film of the series, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, in which he was replaced by David Watson in the role of Cornelius), and also in the television series.

The original series was followed by Tim Burton's remake Planet of the Apes in 2001 and the reboot series begun by Rise of the Planet of the Apes in 2011.[8] In 2001, Planet of the Apes was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[9][10]

Plot

Astronauts Taylor, Landon and Dodge are in deep hibernation when their spaceship crashes into a lake on an unknown planet after a light-speed voyage. They discover their fourth crew mate, Stewart, dead due to a malfunction. The three abandon their ship when it starts sinking; Taylor remains on board long enough to see that the date is November 25, 3978, two thousand and six years after their departure in 1972.

The astronauts set off through a desolate wasteland and discover an oasis in the desert, ignoring eerie scarecrow-like figures around the edge. Their clothes are stolen while they take a swim. The astronauts pursue the thieves, finding their clothes torn to shreds and their supplies pillaged as the perpetrators, a group of mute primitive humans, raid a cornfield. Taylor is shot in the throat and captured by armed gorillas, along with the primitive humans. Dodge is killed and Landon rendered unconscious in the chaos. Taylor is taken to Ape City where he is saved after a blood transfusion administered by two chimpanzees: animal psychologist Zira and surgeon Galen. However, Taylor's throat injury renders him temporarily unable to speak.

Taylor is placed with one of the captive primitive humans, whom he later names Nova. He observes the enhanced society of talking apes and in a strict caste system: the gorillas serving as military forces and labourers; the orangutans overseeing the affairs of government and religion; and intellectual chimpanzees being mostly scientists and doctors. While their society is a theocracy similar to the beginnings of the human Industrial Era, the apes consider the primitive humans as vermin. Humans are hunted, either killed outright, enslaved, or used in scientific experiments. Taylor convinces Zira of his intelligence as she and her fiancé Cornelius, an archaeologist, take an interest in him. Dr. Zaius, their orangutan superior, learns of this and arranges for Taylor to be castrated. Taylor escapes and finds Dodge's stuffed corpse on display in a museum. When Taylor is recaptured, he suddenly regains his speaking abilities and much to the amazement of the onlookers, he shouts: "Take your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!"

A hearing to determine Taylor's origins is convened. Taylor mentions his two comrades, learning that Landon was subjected to a lobotomy that has rendered him catatonic and unable to speak. Believing Taylor to be of a human tribe from beyond their borders, Zaius privately threatens to castrate and lobotomize Taylor for the truth about where he came from. With help from Zira's nephew Lucius, Zira and Cornelius free Taylor and Nova and take them to the Forbidden Zone, a taboo region outside Ape City where Taylor's ship crashed that has been ruled out of bounds for centuries by ape law. While Cornelius and Zira are intent to gather proof of an earlier non-simian civilization which the former came upon a year before to be cleared of heresy, Taylor is more focused on the evolution of the ape world and to prove he is not of that world.

Arriving at the cave, Cornelius is intercepted by Zaius and his soldiers, with Taylor holding them off while threatening to shoot. Zaius agrees to enter the cave to disprove their theories and to avoid physical harm to Cornelius and Zira. Inside, Cornelius displays the remnants of a technologically advanced human society pre-dating simian history. Taylor identifies artifacts such as dentures, eyeglasses, a heart valve, and to the apes' astonishment, a talking children's doll. Zaius admits to Taylor that he always knew of the ancient human civilization. Taylor nonetheless thinks it best to search for answers, despite being warned that he may not like what he finds. Once Taylor and Nova ride off, Dr. Zaius has the gorillas lay explosives to seal off the cave and destroy the evidence while charging Zira, Cornelius and Lucius with heresy.

Taylor and Nova follow the shoreline and discover the remains of the Statue of Liberty, revealing that this "alien" planet is actually Earth long after a nuclear war. Realizing what Zaius meant earlier, Taylor falls to his knees in despair and condemns humanity for destroying the world.

Cast

- Charlton Heston as George Taylor

- Roddy McDowall as Cornelius

- Kim Hunter as Zira

- Maurice Evans as Dr. Zaius

- James Whitmore as President of the Assembly

- James Daly as Honorious

- Linda Harrison as Nova

- Robert Gunner as Landon

- Lou Wagner as Lucius

- Woodrow Parfrey as Maximus

- Jeff Burton as Dodge

- Buck Kartalian as Julius

- Norman Burton as Hunt Leader

- Wright King as Dr. Galen

- Paul Lambert as Minister

Production

Origins

Producer Arthur P. Jacobs bought the rights for the Pierre Boulle novel before its publication in 1963. Jacobs pitched the production to many studios, but was passed over. After Jacobs made a successful debut as a producer doing What a Way to Go! (1964) for 20th Century Fox and begun pre-production of another movie for the studio, Doctor Dolittle, he managed to convince Fox vice-president Richard D. Zanuck to greenlight Planet of the Apes.[11]

One script that came close to being made was written by The Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling, though it was finally rejected for a number of reasons. A prime concern was cost, as the technologically advanced ape society portrayed by Serling's script would have involved expensive sets, props, and special effects. The previously blacklisted screenwriter Michael Wilson was brought in to rewrite Serling's script and, as suggested by director Franklin J. Schaffner, the ape society was made more primitive as a way of reducing costs. Serling's stylized twist ending was retained, and became one of the most famous movie endings of all time. The exact location and state of decay of the Statue of Liberty changed over several storyboards. One version depicted the statue buried up to its nose in the middle of a jungle while another depicted the statue in pieces.[11]

To convince the Fox Studio that a Planet of the Apes film could be made, the producers shot a brief test scene from a Rod Serling draft of the script, using early versions of the ape makeup, on March 8, 1966. Charlton Heston appeared as an early version of Taylor (named Thomas, as he was in the Serling-penned drafts), Edward G. Robinson appeared as Zaius, while two then-unknown Fox contract actors, James Brolin and Linda Harrison, played Cornelius and Zira. This test footage is included on several DVD releases of the film, as well as the documentary Behind the Planet of the Apes. Linda Harrison, at the time, the girlfriend of studio chief Richard D. Zanuck, went on to play Nova in the 1968 film and its first sequel, and had a cameo in Tim Burton's Planet of the Apes more than 30 years later, which was also produced by Zanuck. Although Harrison often opined that the producers had always had her in mind for the role of Nova, they had, in fact, considered first Ursula Andress, then Raquel Welch, and Angelique Pettyjohn. When these three women proved unavailable or uninterested, Zanuck gave the part to Harrison. Dr. Zaius was originally to have been played by Robinson, but he backed out due to the heavy makeup and long sessions required to apply it.[12] Robinson's final film, Soylent Green (1973), starred his one-time Ten Commandments (1956) co-star, Heston.

Michael Wilson's rewrite kept the basic structure of Serling's screenplay but rewrote all the dialogue and set the script in a more primitive society. According to associate producer Mort Abrahams an additional uncredited writer (his only recollection was that the writer's last name was Kelly) polished the script, rewrote some of the dialogue and included some of the more heavy-handed tongue-in-cheek dialogue ("I never met an ape I didn't like") which wasn't in either Serling or Wilson's drafts. According to Abraham some scenes, such as the one where the judges imitate the "See no evil, speak no evil and hear no evil" monkeys, were improvised on the set by director Franklin J. Schaffner and kept in the final film because of the audience reaction during test screenings prior to release.[13] During filming John Chambers, who designed prosthetic make-up in the film,[6] held training sessions at 20th Century-Fox studios, where he mentored other make-up artists of the film.[14]

Filming

Filming began on May 21, 1967, and ended on August 10, 1967. Most of the early scenes of a desert-like terrain were shot in northern Arizona near the Grand Canyon, the Colorado River, Lake Powell,[13]:61 Glen Canyon[13]:61 and other locations near Page, Arizona[13]:59 Most scenes of the ape village, interiors and exteriors, were filmed on the Fox Ranch[13]:68 in Malibu Creek State Park, northwest of Los Angeles, essentially the backlot of 20th Century Fox. The concluding beach scenes were filmed on a stretch of California seacoast between Malibu and Oxnard with cliffs that towered 130 feet (40 m) above the shore. Reaching the beach on foot was virtually impossible, so cast, crew, film equipment, and even horses had to be lowered in by helicopter.[13]:79

The home movies of Roddy McDowall (on YouTube) show makeup, the Ape Village set and the beach site/set - a wooden ramp was built around the point from Westward Beach to Pirates Cove for access to the beach set. The remains of the Statue of Liberty were shot in a secluded cove on the far eastern end of Westward Beach, between Zuma Beach and Point Dume in Malibu.[15] As noted in the documentary Behind the Planet of the Apes,[11] the special effect shot of the half-buried statue was achieved by seamlessly blending a matte painting with existing cliffs. The shot looking down at Taylor was done from a 70-foot (21 m) scaffold, angled over a 1/2-scale papier-mache model of the Statue. The actors in Planet of the Apes were so affected by their roles and wardrobe that, when not shooting, they automatically segregated themselves with the species they were portraying.[16]

Taylor's spacecraft

The spacecraft onscreen is never actually named in the film; however, for the 40th anniversary release of the Blu-ray edition of the film, in the short film created for the release titled A Public Service Announcement from ANSA, the ship is named Liberty 1.[17] The ship had originally been called "Immigrant One" in an early draft of the script, and then called "Air Force One" in a test set of Topps Collectible cards, and dubbed "Icarus" by a fan; that name gained popularity among Ape fandom.[17][18]

Reception

Critical response

Planet of the Apes was met with critical acclaim and is widely regarded as a classic film and one of the best films of 1968, applauded for its imagination and its commentary on a possible world gone upside down.[19][20] Pauline Kael called it "one of the most entertaining science-fiction fantasies ever to come out of Hollywood."[21] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars out of four and called it "much better than I expected it to be. It is quickly paced, completely entertaining, and its philosophical pretensions don't get in the way."[22] Renata Adler of The New York Times wrote, "It is no good at all, but fun, at moments, to watch."[23] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety called it "an amazing film." He thought the script "at times digresses into low comedy," but "the totality of the film works very well."[24] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "A triumph of artistry and imagination, it is at once a timely parable and a grand adventure on an epic scale."[25] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it an "amusing and unusually engrossing picture."[26]

As of June 26, 2020, the film held an 86% approval rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 59 reviews with an average rating of 7.63/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Planet of the Apes raises thought-provoking questions about our culture without letting social commentary get in the way of the drama and action."[27] In 2008, the film was selected by Empire magazine as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[28]

Box office

According to Fox records the film required $12,850,000 in rentals to break even and made $20,825,000 so made a considerable profit for the studio.[29]

Accolades

The film won an honorary Academy Award for John Chambers for his outstanding make-up achievement. The film was nominated for Best Costume Design (Morton Haack) and Best Original Score for a Motion Picture (not a Musical) (Jerry Goldsmith).[30] The score is known for its avant-garde compositional techniques, as well as the use of unusual percussion instruments and extended performance techniques, as well as his 12-tone music (the violin part using all 12 chromatic notes) to give an eerie, unsettled feel to the planet, mirroring the sense of placelessness.

- American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies—Nominated[31]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills—#59

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Colonel George Taylor—Nominated Hero[32]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Take your stinking paws off me, you damned dirty ape!"—#66

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores—#18

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)—Nominated[33]

- AFI's 10 Top 10—Nominated Science Fiction Film[34]

Among the 25 Films inducted into the Library of Congress for the year 2001.[35]

Legacy

Original series sequels

Writer Rod Serling was brought back to work on an outline for a sequel. Serling's outline was ultimately discarded in favor of a story by associate producer Mort Abrahams and writer Paul Dehn, which became the basis for Beneath the Planet of the Apes.[13] The original film series had four sequels:

Television series

- Planet of the Apes (1974)

- Return to the Planet of the Apes (animated) (1975)

Remake

- Planet of the Apes (2001): The film was a re-imagining of the original film, directed by Tim Burton.

Reboot series

- Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011): A series reboot, directed by Rupert Wyatt, was released on August 5, 2011 to critical and commercial success. It is the first installment in the new series of films.[8]

- Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014): The second entry in the Planet of the Apes reboot series, directed by Matt Reeves, was released on July 11, 2014.[36][37]

- War for the Planet of the Apes (2017): The third film in the reboot series, directed by Matt Reeves, was released on July 14, 2017.[38][39][40]

Documentaries

- Behind the Planet of the Apes (1998) A feature-length making-of documentary on the original film and TV series, hosted by Roddy McDowall.

Comics

- Comic book adaptations of the films were published by Gold Key (1970) and Marvel Comics (b/w magazine 1974-1977,[41] color comic book 1975-76).[42] Malibu Comics reprinted the Marvel adaptations when it held the license in the early 1990s, as well as producing new stories including Ape Nation, a crossover with Alien Nation. Dark Horse Comics published an adaptation for the 2001 Tim Burton film. Currently Boom! Studios has the licensing rights to Planet of the Apes. Its stories tell the tale of Ape City and its inhabitants before Taylor arrived. In July 2014, Boom! Studios and IDW Publishing published a crossover between Planet of the Apes and the original Star Trek series. In 2018, the original 1968 film's unused screenplay by Rod Serling was adapted into a graphic novel entitled Planet of the Apes: Visionaries.[43][44]

In popular culture

A parody of the film series titled "The Milking of the Planet That Went Ape" was published in Mad Magazine. It was illustrated by Mort Drucker and written by Arnie Kogen in regular issue #157, March 1973.[45]

The Simpsons parodied the film in the episode "A Fish Called Selma". Troy McClure (who appeared in such films as Today We Kill, Tomorrow We Die and Gladys the Groovy Mule) starred in a musical version called Stop the Planet of the Apes, I Want to Get Off.[46]

Gallery

The crash of the astronauts' spacecraft was partially filmed in and around Lake Powell.

The crash of the astronauts' spacecraft was partially filmed in and around Lake Powell. Horseshoe Bend on the Colorado River, near Page, Arizona, was a part of the Forbidden Zone, through which Taylor, Zira, and Cornelius fled Ape City.

Horseshoe Bend on the Colorado River, near Page, Arizona, was a part of the Forbidden Zone, through which Taylor, Zira, and Cornelius fled Ape City. Malibu Creek State Park, part of which was formerly the 20th Century Fox Movie Ranch, was the location of the astronauts' initial encounter with primitive humans and superior apes, and of Cornelius, Zira and Taylor's escape from Ape City.

Malibu Creek State Park, part of which was formerly the 20th Century Fox Movie Ranch, was the location of the astronauts' initial encounter with primitive humans and superior apes, and of Cornelius, Zira and Taylor's escape from Ape City.- The final scene was filmed at Point Dume's Westward Beach on the Malibu coast.

The cliff face of Point Dume is obscured by the matte painting of the Statue of Liberty.

The cliff face of Point Dume is obscured by the matte painting of the Statue of Liberty.

See also

- List of American films of 1968

- Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction, about the film genre, with a list of related films

- Survival film, about the film genre, with a list of related films

References

- "Planet of the Apes". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- "The Planet of the Apes (1968) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- Leong, Anthony. "Those Damned Dirty Apes!". www.mediacircus.net. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- Webb, Gordon C. (July 1998). "30 Years Later: Rod Serling's Settling the Debate over Who Wrote What, and When". www.rodserling.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- "Planet of the Apes (1968)". Box Office Mojo. January 1, 1982. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Brian Pendreigh (September 7, 2001). "Obituary: John Chambers: Make-up master responsible for Hollywood's finest space-age creatures". The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Planet of the Apes (1968) A Film Review by James Berardinelli". www.reelviews.net. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Lussier, Germain (April 14, 2011). "RISE OF THE PLANET OF THE APES Set Visit and Video Blog". Collider. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- American Movie Classics (1998). Behind the Planet of the Apes. Planet of the Apes Blu-Ray: 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment.

- Pulver, Andrew (June 24, 2005). "Monkey business". The Guardian. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- Russo, Joe; Landsman, Larry; Gross, Edward (2001). Planet of the Apes Revisited: The Behind-The Scenes Story of the Classic Science Fiction Saga (1st ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0312252390.

- Tom Weaver (2010). Sci-Fi Swarm and Horror Horde: Interviews with 62 Filmmakers. McFarland. p. 314. ISBN 0786458313.

- "Film locations for Planet of the Apes (1968)". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "Apes Trivia". Theforbidden-zone.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Handley, Rich (2009). Timeline of the Planet of the Apes: The Definitive Chronology. Hasslein Books. p. 11. ISBN 9780615253923.

- Key, Jim (January 1, 1999). "The Flight of the Icarus". Sci-Fi & Fantasy Models International. Next Millennium Publishing Ltd (38): 14.

- "The Greatest Films of 1968". AMC Filmsite.org. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- "The Best Movies of 1968 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- Kael, Pauline (2011) [1991]. 5001 Nights at the Movies. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 586. ISBN 978-1-250-03357-4.

- Ebert, Roger (April 15, 1968). "Planet of the Apes". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Adler, Renata (February 9, 1968). "Monkey Business". The New York Times 55.

- Murphy, Arthur D. (February 7, 1968). "Film Reviews: Planet of the Apes". Variety. 6.

- Thomas, Kevin (March 24, 1968). "'Planet of Apes' Out of This World". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 18.

- Coe, Richard L. (April 12, 1968). "The Simians Take a Planet". The Washington Post. B6.

- "Planet of the Apes (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire Magazine. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- Silverman, Stephen M (1988). The Fox that got away : the last days of the Zanuck dynasty at Twentieth Century-Fox. L. Stuart. p. 327.

- Wiley, Mason; Bona, Damien (1986). MacColl, Gail (ed.). Inside Oscar: The Unofficial History of the Academy Awards. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 768.

- "America's Greatest Movies" (PDF). AFI. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "AFI'S 100 Years 100 Heroes & Villains" (PDF). AFI. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "AFI 100 Years 100 Movies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "AFI Ballot" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Lussier, Germain (October 1, 2012). "Matt Reeves Confirmed to Helm 'Dawn of the Planet of the Apes'". Slashfilm.com.

- Douglas, Edward (December 10, 2013). "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes Moves Up One Week". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- McNary, Dave (January 5, 2015). "Channing Tatum's X-Men Spinoff to Hit Theaters in 2016". Variety. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- Sneider, Jeff (January 5, 2015). "Channing Tatum's 'Gambit' Gets 2016 Release Date, 'Fantastic Four' Sequel Moves Up". Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- Goldberg, Matt (May 14, 2015). "New Planet of the Apes Movie Title Revealed". Collider. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- Planet of the Apes at the Grand Comics Database

- Adventures on the Planet of the Apes at the Grand Comics Database

- McMillan, Graeme (February 1, 2018). "Rod Serling's 'Planet of the Apes' Script Inspires Graphic Novel (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Fitzpatrick, Insha (September 3, 2018). "Planet of the Apes: Visionaries is Unpredictable, Stunning and Wild". Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site - Mad #157". Madcoversite.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Fox, Jesse David (July 17, 2017). "An Oral History of The Simpsons' Classic Planet of the Apes Musical". Slate. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Planet of the Apes |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Planet of the Apes. |

- Planet of the Apes essay by John Wills at the National Film Registry

- Official website

- Planet of the Apes on IMDb

- Planet of the Apes at AllMovie

- Planet of the Apes at Rotten Tomatoes

- Planet of the Apes at Box Office Mojo

- Planet of the Apes essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 632-633

.svg.png)