Indra's net

Indra's net (also called Indra's jewels or Indra's pearls, Sanskrit Indrajāla) is a metaphor used to illustrate the concepts of Śūnyatā (emptiness),[1] pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination),[2] and interpenetration[3] in Buddhist philosophy.

The metaphor's earliest known reference is found in the Atharva Veda. It was further developed by the Mahayana school in the 3rd century Avatamsaka Sutra and later by the Huayan school between the 6th and 8th centuries.[1]

Avatamsaka Sutra

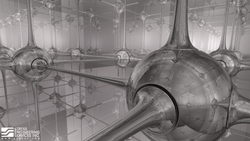

"Indra's net" is an infinitely large net of cords owned by the Vedic deva Indra, which hangs over his palace on Mount Meru, the axis mundi of Buddhist and Hindu cosmology. In this metaphor, Indra's net has a multifaceted jewel at each vertex, and each jewel is reflected in all of the other jewels.[4]

In the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, which follows the Avatamsaka Sutra, the image of "Indra's net" is used to describe the interconnectedness of the universe.[4] Francis H. Cook describes Indra's net thus:

Far away in the heavenly abode of the great god Indra, there is a wonderful net which has been hung by some cunning artificer in such a manner that it stretches out infinitely in all directions. In accordance with the extravagant tastes of deities, the artificer has hung a single glittering jewel in each "eye" of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number. There hang the jewels, glittering "like" stars in the first magnitude, a wonderful sight to behold. If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring.[5]

The Buddha in the Avatamsaka Sutra's 30th book states a similar idea:

- If untold buddha-lands are reduced to atoms,

- In one atom are untold lands,

- And as in one,

- So in each.

- The atoms to which these buddha-lands are reduced in an instant are unspeakable,

- And so are the atoms of continuous reduction moment to moment

- Going on for untold eons;

- These atoms contain lands unspeakably many,

- And the atoms in these lands are even harder to tell of.[6]

Book 30 of the sutra is named "The Incalculable" because it focuses on the idea of the infinitude of the universe and, as Cleary notes, concludes that "the cosmos is unutterably infinite, and hence so is the total scope and detail of knowledge and activity of enlightenment."[7] In another part of the sutra, the Buddhas' knowledge of all phenomena is referred to by this metaphor:

They [Buddhas] know all phenomena come from interdependent origination.

They know all world systems exhaustively. They know all the

different phenomena in all worlds, interrelated in Indra's net.[8]

In Huayan texts

The metaphor of Indra's net of jewels plays an essential role in the Chinese Huayan school,[9] where it is used to describe the interpenetration (Wylie: zung-'jug; Sanskrit: yuganaddha) of microcosmos and macrocosmos.[10] The Huayan text entitled "Calming and Contemplation in the Five Teachings of Huayan" (Huayan wujiao zhiguan 華嚴五教止觀, T1867) attributed to the first Huayan patriarch Dushun (557–640) gives an extended overview of this concept:

The manner in which all dharmas interpenetrate is like an imperial net of celestial jewels extending in all directions infinitely, without limit. … As for the imperial net of heavenly jewels, it is known as Indra’s Net, a net which is made entirely of jewels. Because of the clarity of the jewels, they are all reflected in and enter into each other, ad infinitum. Within each jewel, simultaneously, is reflected the whole net. Ultimately, nothing comes or goes. If we now turn to the southwest, we can pick one particular jewel and examine it closely. This individual jewel can immediately reflect the image of every other jewel.

As is the case with this jewel, this is furthermore the case with all the rest of the jewels–each and every jewel simultaneously and immediately reflects each and every other jewel, ad infinitum. The image of each of these limitless jewels is within one jewel, appearing brilliantly. None of the other jewels interfere with this. When one sits within one jewel, one is simultaneously sitting in all the infinite jewels in all ten directions. How is this so? Because within each jewel are present all jewels. If all jewels are present within each jewel, it is also the case that if you sit in one jewel you sit in all jewels at the same time. The inverse is also understood in the same way. Just as one goes into one jewel and thus enters every other jewel while never leaving this one jewel, so too one enters any jewel while never leaving this particular jewel.[11]

The Huayan Patriarch Fazang (643–712) used the golden statue of a lion to demonstrate the Huayan vision of interpenetration to empress Wu:[12]

In each of the lion's eyes, in its ears, limbs, and so forth, down to each and every single hair, there is a golden lion. All the lions embraced by each and every hair simultaneously and instantaneously enter into one single hair. Thus, in each and every hair there are an infinite number of lions... The progression is infinite, like the jewels of Celestial Lord Indra's Net: a realm-embracing-realm ad infinitum is thus established, and is called the realm of Indra's Net.[12]

Atharva Veda

According to Rajiv Malhotra, the earliest reference to a net belonging to Indra is in the Atharva Veda (c. 1000 BCE).[13] Verse 8.8.6. says:

Vast indeed is the tactical net of great Indra, mighty of action and tempestuous of great speed. By that net, O Indra, pounce upon all the enemies so that none of the enemies may escape the arrest and punishment.[14]

And verse 8.8.8. says:

This great world is the power net of mighty Indra, greater than the great. By that Indra-net of boundless reach, I hold all those enemies with the dark cover of vision, mind and senses.[15]

The net was one of the weapons of the sky-god Indra, used to snare and entangle enemies.[16] The net also signifies magic or illusion.[17] According to Teun Goudriaan, Indra is conceived in the Rig Veda as a great magician, tricking his enemies with their own weapons, thereby continuing human life and prosperity on earth.[18] Indra became associated with earthly magic, as reflected in the term indrajalam, "Indra's Net", the name given to the occult practices magicians.[18] According to Goudriaan, the term indrajalam seems to originate in verse 8.8.8 from the Atharva Veda, of which Goudriaan gives a different translation:[19]

This world was the net of the great Sakra (Indra), of mighty size; by means of this net of Indra I envelop all those people with darkness.[19]

According to Goudriaan, the speaker pretends to use a weapon of cosmical size.[19] The net being referred to here

...was characterized there as the antariksa-, the intermediate space between heaven and earth, while the directions of the sky were the net's sticks (dandah) by means of which it was fastened to the earth. With this net Indra conquered all his enemies.[19]

Modern and Western references

Gödel, Escher, Bach

In Gödel, Escher, Bach (1979), Douglas Hofstadter uses Indra's net as a metaphor for the complex interconnected networks formed by relationships between objects in a system—including social networks, the interactions of particles, and the "symbols" that stand for ideas in a brain or intelligent computer.[21]

Vermeer's Hat

In Vermeer's Hat (2007), a history book written by Timothy Brook, the author uses the metaphor:

Buddhism uses a similar image to describe the interconnectedness of all phenomena. It is called Indra's Net. When Indra fashioned the world, he made it as a web, and at every knot in the web is tied a pearl. Everything that exists, or has ever existed, every idea that can be thought about, every datum that is true—every dharma, in the language of Indian philosophy—is a pearl in Indra's net. Not only is every pearl tied to every other pearl by virtue of the web on which they hang, but on the surface of every pearl is reflected every other jewel on the net. Everything that exists in Indra's web implies all else that exists.[22]

Writing in The Spectator, Sarah Burton explains that Brook uses the metaphor, and its interconnectedness,

to help understand the multiplicity of causes and effects producing the way we are and the way we were [...] In the same way, the journeys through Brook's picture-portals intersect with each other, at the same time shedding light on each other.[23]

Indra's Net: Defending Hinduism's Philosophical Unity

In Indra's Net (2014), Rajiv Malhotra uses the image of Indra's net as a metaphor for

the profound cosmology and outlook that permeates Hinduism. Indra's Net symbolizes the universe as a web of connections and interdependences [...] I seek to revive it as the foundation for Vedic cosmology and show how it went on to become the central principle of Buddhism, and from there spread into mainstream Western discourse across several disciplines.[24]

See also

- Brahmajala Sutra

- Coincidentia oppositorum

- Fazang

- Hosshin Kingdom

- Indra's thunderbolt

- Macrocosm and microcosm

- Metamodernism

- Rhizome (philosophy)

- Śakra (Buddhism)

- The Net (substance)

- Three Spheres II

References

- Jones 2003, p. 16.

- Lee 2005, p. 473.

- Odin 1982, p. 17

- Kabat-Zinn 2000, p. 225.

- Cook 1977.

- Cleary. The Flower Ornament Scripture A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra, 1993, page 891-92

- Cleary. The Flower Ornament Scripture A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra, 1993, page 44

- Cleary. The Flower Ornament Scripture A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra, 1993, page 925.

- Cook 1977, p. 2.

- Odin 1982, p. 16-17.

- Fox, Alan. The Practice of Huayan Buddhism, http://www.fgu.edu.tw/~cbs/pdf/2013%E8%AB%96%E6%96%87%E9%9B%86/q16.pdf Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Odin 1982, p. 17.

- Malhotra 2014, p. 4-5, 210.

- Ram 2013, p. 910.

- Ram 2013, p. 910-911.

- Beer 2003, p. 154.

- Debroy 2013.

- Goudriaan 1978, p. 211.

- Goudriaan 1978, p. 214.

- "Alan Watts Podcast – Following the Middle Way #3". alanwattspodcast.com (Podcast). 31 August 2008.

- Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1999), Gödel, Escher, Bach, Basic Books, p. 266, ISBN 0-465-02656-7

- Brook, Timothy (2009). Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World. London: Profile Books. p. 22. ISBN 1847652549. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Burton, Sarah (2 August 2008). "The Net Result". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Malhotra 2014, p. 4.

Sources

Published sources

- Beer, Robert (2003), The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols, Serindia Publications

- Burley, Mikel (2007), Classical Samkhya and Yoga: An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge

- Cook, Francis H. (1977), Hua-Yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra, Penn State Press, ISBN 0-271-02190-X

- Debroy, Bibek (2013), Mahabharata, Volume 7 (Google eBoek), Penguin UK

- Jones, Ken H. (2003), The New Social Face of Buddhism: A Call to Action, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-365-6

- Goudriaan, Teun (1978), Maya: Divine And Human, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon; Watson, Gay; Batchelor, Stephen; Claxton, Guy (2000), Indra's Net at Work: The Mainstreaming of Dharma Practice in Society. In: The Psychology of Awakening: Buddhism, Science, and Our Day-to-Day Lives, Weiser, ISBN 1-57863-172-6

- Lee, Kwang-Sae (2005), East and West: Fusion of Horizons, Homa & Sekey Books, ISBN 1-931907-26-9

- Malhotra, Rajiv (2014), Indra's Net: Defending Hinduism's Philosophical Unity, Noida, India: HarperCollins Publishers India, ISBN 9789351362449 ISBN 9351362442, OCLC 871215576

- Odin, Steve (1982), Process Metaphysics and Hua-Yen Buddhism: A Critical Study of Cumulative Penetration Vs. Interpenetration, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-87395-568-4

- Ram, Tulsi (2013), Atharva Veda: Authentic English Translation, Agniveer, pp. 910–911, retrieved 24 June 2014

Web-sources

Further reading

- Cleary, Thomas (1983), Entry Into the Inconceivable: An Introduction to Hua-yen Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1697-1.