Hurricane Gaston (2004)

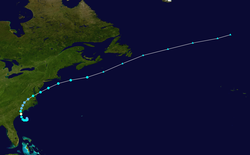

Hurricane Gaston was a minimal hurricane that made landfall in South Carolina on August 29, 2004. It then crossed North Carolina and Virginia before exiting to the northeast and dissipating. The storm killed nine people – eight of them directly – and caused $130 million (2004 USD) in damage. Gaston produced torrential downpours that inundated Richmond, Virginia. Although originally designated a tropical storm, Gaston was reclassified as a hurricane when post-storm analysis revealed it had maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h).

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

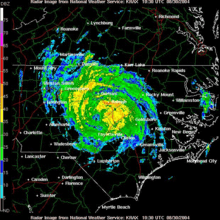

Hurricane Gaston shortly after moving ashore on August 29 | |

| Formed | August 27, 2004 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 3, 2004 |

| (Extratropical after September 1) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 75 mph (120 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 985 mbar (hPa); 29.09 inHg |

| Fatalities | 8 direct, 1 indirect |

| Damage | $130 million (2004 USD) |

| Areas affected | South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Massachusetts |

| Part of the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Meteorological history

On August 22, 2004, a cold front—the same front which eventually spawned Tropical Storm Hermine—moved off the coast of the Carolinas and drifted southward before stalling on August 24. On August 25, Surface observations indicated that a broad low pressure area developed along the deteriorating frontal boundary. Convection remained sporadic and disorganized, until thunderstorm activity began to increase and the system developed banding structure on August 26. At 1200 UTC on August 27, the low organized, and was designated as Tropical Depression Seven while located about 130 mi (210 km) east-southeast of Charleston, South Carolina.[1]

Because steering currents were initially weak, the depression was nearly stationary in movement, although forecasts predicted a ridge to the northeast of the system would gradually steer it to the west. The cyclone was situated over warm ocean waters and contained good anticyclonic flow, leading forecast models to predict at least moderate intensification.[2] Later that same day, it gradually drifted southwest and convective banding continued to increase. At 1100 UTC on August 28, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Gaston.[1] An Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters aircraft completed a flight into Gaston, revealing that the intensity was higher than previously reported. At the time, it was believed that Gaston had reached peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h), placing it very close to hurricane status.[3] However, during post-season analysis, it was discovered that Gaston had briefly attained Category 1 Hurricane intensity at 1800 UTC on August 28.[1]

At 1400 UTC on August 29, Gaston made landfall at Awendaw, South Carolina, between Charleston and McClellanville, as a Category 1 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (121 km/h).[1] The storm quickly weakened to a tropical storm as it continued northward through South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia, and it began to gradually move north-northeastward.[4] At 0000 UTC on August 30, the storm weakened to a tropical depression over northeastern South Carolina. As it accelerated to the northeast, it emerged in the open waters of the Chesapeake Bay and regained tropical storm status late on August 30.[5] Initially, the system maintained a good radar signature, although satellite imagery soon indicated that convection became limited in intensity and coverage. Also, a front-like band appeared to be forming southeast of the center, which indicated signs of weakening.[6] At 0600 UTC on August 31, Gaston crossed the Delmarva Peninsula for the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.[1] The system began to lose tropical characteristics as it became associated with the frontal system, although there was still some thunderstorm activity wrapped around the center.[7] Forward speed increased to about 30 mph (48 km/h),[1] and over 60 °F (16 °C) water[8] the storm lost all of its tropical characteristics early on September 1, and became an extratropical cyclone south of the Canadian Maritimes.[1] The extratropical remnants of Gaston were absorbed by a larger extratropical system on September 3, about 750 mi (1,210 km) south-southeast of Reykjavík, Iceland.[1]

Preparations

On August 27, shortly after the formation of Gaston, tropical storm watches were issued for coastal locations from Surf City, North Carolina to Fernandina Beach, Florida. On August 28, a tropical storm warning was put into effect from the Savannah River to the inlet of the Little River;[9] shortly after, the tropical storm watch was modified to a hurricane at 0000 UTC on August 29. At 0300 UTC the tropical storm watch issued for north of Little River Inlet to Surf City, North Carolina was upgraded to a tropical storm warning. The tropical storm watch issued for coastal Georgia from south of the Savannah River to Fernadina Beach, Florida remained in effect.[10] At 1500 UTC, all hurricane watches and warnings were discontinued and by 0000 UTC on August 30, all advisories were subsequently discontinued.[1]

In South Carolina, residents living in low-lying Charleston and Georgetown counties as well as those living in mobile homes were urged to evacuate or move to higher grounds.[11] No mandatory evacuations were ordered, although voluntary evacuations were advised for the Barrier Island.[12] In those locations and other coastal counties, it is estimated that 100–200 people sought protection in 6 shelters.[12] In Charleston and surrounding areas, bridges were closed to large vehicles and trucks. In anticipation of Gaston, mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr advised, "The best advice for everyone is to stay put. Stay put, don't go out please. This will be past us quickly and let's just stay out of harm's way and get it behind us."[11]

By August 29, flood watches were in effect for eastern South Carolina and eastern and southern North Carolina.[13] On August 30, flood warnings were issued for portions of central Virginia, and tornado watches were put into effect for parts of southeast Virginia and northern North Carolina.[14] In Charlotte, North Carolina, an estimated 30 National Guard soldiers were activated to assist in helping in flooded areas.[15]

Impact

South Carolina

On August 29, Gaston made landfall near Bulls Bay with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). At the Isle of Palms, a gust of 81 mph (130 km/h) was reported by a storm chaser.[1] The heaviest rain fell from Williamsburg County, through Florence and Darlington counties,[16] where rainfall amounts ranged from 5 in (130 mm) to over 10 in (250 mm).[1] This resulted in flash flooding, up to 5 ft (1.5 m) deep in some cases, which overwashed and closed several roads. One F1 tornado was reported in Marlboro County, although damage was unknown.[1]

Storm surge ranged from 4 to 4.5 ft (1.2 to 1.4 m) feet in Bulls Bay. Widespread wind damage occurred in northern Charleston County and in Berkeley County. The high winds blew down numerous trees and branches, destroying eight homes. In total over 3,000 structures sustained minor to significant damage, and trees fell on several vehicles. Several lamp posts, power lines, mailboxes, signs and fences were damaged or destroyed by fallen debris. The Lumber River crested at a record high of nearly 8 feet above flood stage, forcing the evacuation of many homes and flooding farmlands.[16] In Berkeley County, 20 structures were severely damaged or destroyed, and dozens of other structures suffered minor flooding damage.[1] Overall, damage in South Carolina rose to over $40 million.[1] During the height of the storm over 150,000 customers were without power.[17]

North Carolina

Gaston tracked into North Carolina as a tropical depression early on August 30, producing up to 6.10 in (155 mm) of rain near Red Springs.[1] Wind gusts peaked at 45 mph (72 km/h) at the Laurinburg-Maxton Airport. Also, the Elizabeth City Coast Guard Air Station reported gusts of 39 mph (63 km/h).[18] These winds knocked out power to 6,500 customers.[19] In Chatham County and Johnston County, numerous trees were blown down. A fallen tree landed on a post office, inflicting damage to the roof and back porch.[20] Windspread flooding occurred as a result of the heavy rainfall. In Raleigh, the Marsh Creek overflowed its banks, flooding several trucks and closing numerous onramps to Interstate 40.[21] Persistent rainfall on the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge caused the Linville River near Linville to rapidly rise, flooding a bridge. Many other small creeks and rivers overflowed which forced some evacuations in the early hours of the morning.[22] In Selma, 6 to 12 in (150 to 300 mm) of water was reported on Interstate 95.[23] Additionally, a tornado spawned by the storm damaged several homes in Hoke County.[18]

Virginia

As the storm tracked northward through Virginia as a tropical depression, it produced torrential rainfall, peaking at 12.60 in (320 mm) in Richmond.[24] The storm strengthened over Virginia, as it pivoted from a northerly track to a northeasterly track nearly over the Richmond area, which led to the afternoon of exceptional rainfall, with the epicenter over Richmond. There were also numerous reports of rainfall over 10 in (250 mm), primarily in the central portions of the state.[1] The heavy precipitation caused moderate to severe damage in Chesterfield, Dinwiddie, Hanover, Henrico, and Prince George counties, where 350 homes and 230 businesses were damaged or destroyed, and many roads were closed due to high water. Hanover, Virginia reported almost a foot of rain, 11.7 inches to be exact.[1] The heaviest-hit location was downtown Richmond, where 20 blocks of the city were under water. In the historic district, a brick building collapsed[19] and dozens of other structures received flood damage as water reached 10 ft (3.0 m) in some places.[25] It is estimated that 29 homes were declared uninhabitable.[26] At the Richmond battlefield, a foot of standing water left $32,500 (2004 USD) in damage.[27] Rushing water floated automobiles and crashed them into buildings in some parts of the city.[28] Also, over 120 roads were closed within Richmond, with several more in other areas.[19] The stretch of Interstate 95 in the city was closed as flash flooding caused 20 traffic accidents.[29] An intersection was closed due to a 30 ft (9.1 m) crest as a result of flowing underground water.[30] Along the James River, swift–water rescues were required to bring people who were stranded in their cars to safety. Additionally, at least 1,000 people were forced from their homes.[29] In total, damage from flooding in the city totaled to over $20 million (2004 USD)[25] and nine people were killed, eight directly.[1]

| F0 | < 73 mph | Light damage |

|---|---|---|

| F1 | 73–112 mph | Moderate damage |

| F2 | 113–157 mph | Considerable damage |

| F3 | 158–206 mph | Severe damage |

| F4 | 207–260 mph | Devastating damage |

| F5 | 261–318 mph | Incredible damage |

Gaston touched off numerous tornadoes in the state. In all, 19 tornadoes were confirmed in Virginia.[31] These were mostly weak, commonly ranking F0 or F1 on the Fujita Scale. Damage from the tornadoes was mostly minor, and typically limited to fallen trees and light structural damage.[31] A tornado in Hopewell downed 25–30 trees and damaged a shed.[32] Also, an F0 tornado in Nottoway County tore metal roofing off the roof of a church.[33]

Atlantic Canada

On August 30, the hurricane produced a shield of rain just off the coast of mainland Nova Scotia, although on Sable Island 72 mm (2.8 in) of rain fell in four hours.[34] Other than reports of light rainfall there was no damage and little if any effects in the region.[34]

Aftermath in Richmond

Much of downtown Richmond was a mess; many buildings in the disaster area were condemned. A story in the Richmond Times-Dispatch said, "The air downtown is ripe with the smell of fresh mud and rotting vegetables."[35] On August 31, Governor Mark Warner declared a state of emergency.[36]

Consumer concerns

Approximately 2,000 cars and trucks were reported towed from the disaster area following Gaston. Consequently, the flooded-out cars and trucks, known as "flood cars," were sold on used car lots at a cheap price. There were also isolated reports of scamming.[37]

Economic impact

Many small businesses in the Richmond area were hit hard by the flooding brought by Gaston. While some managed to reopen, some closed for longer periods of time or even permanently. After the storm, city officials cordoned off the historic Shockoe Bottom area (roughly between 15th and 18th Streets, south of East Broad Street), so building inspectors and crews from the Department of Public Utilities and Dominion Virginia Power could ensure that the area's stores, restaurants, warehouses, and apartments were safe to enter and that there were no gas leaks.

"Property insurance by itself probably won't cover damages," said a spokesman for the State Corporation Commission. "However, many businesses in the Bottom have flood insurance, since most lenders would make it a requirement in flood-prone areas..."

"The best other businesses can hope for, in the rebuilding process, is federal assistance through grant money and low-interest loans if Richmond is declared a federal disaster area," he later said.

The flooding from Gaston also affected VDOT's emergency road repair fund. VDOT estimated that repairing the wrecked roads and bridges would cost $10 to $20 million, and that did not cover damage to streets and roads that the city of Richmond and Henrico County maintain.

Already stretching its budget thin, VDOT had to set $16 million aside for major projects other than snow removal, leaving very little to pay for storm damage.

Recovery and criticism

After the storm, the Richmond city government poured money into reconstruction and expansion of the drainage system and new emergency-notification technology that officials said would make Richmond ready for future storms. Beginning in 2006, the city had spent $1.9 million on projects to mitigate the impact of major rainfalls. The city had also stepped up the frequency of its inspections and cleanings of the existing drain system, and has installed a new flash flood warning system.

$8.7 million was spent to help the victims of the storm, much of it from FEMA. In Shockoe Bottom, most of the buildings were rebuilt and most of the businesses were back up and running. Some business owners say that the relief came too late.

This sparked criticism of the city government in response to Hurricane Gaston. Many complained about potholes lining the roads, brick sidewalks that were a mess, and faded crosswalks. Also, because of poor drainage, streets was covered with a thick layer of silt and because of the lack of trash cans, storm debris was everywhere.

Even a year later, some of the damage from Gaston still lingered.

See also

References

- James L. Franklin, Daniel P. Brown and Colin McAdie (2004). "Hurricane Gaston Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- Stewart/Beven (2004). "Tropical Depression 7 Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Franklin (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 7". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- Pasch (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 9". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- Stewart (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 14". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- Beven (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- Pasch (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 17". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- Franklin (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 18". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- "Tropical Storm Gaston Advisory". National Hurricane Center Past Advisories. National Weather Service/National Hurricane Center. August 24, 2004. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

A TROPICAL STORM WARNING REMAINS IN EFFECT ALONG THE SOUTH CAROLINA COAST FROM THE SAVANNAH RIVER TO LITTLE RIVER INLET.

- "TROPICAL STORM GASTON ADVISORY NUMBER 6". Past Advisories. National Weather Service/National Hurricane Center. August 28, 2004. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- Associated Press (2004). "S.C Hit by Tropical Storm Gaston". Insurance Journal. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- Charleston, SC NWS (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Post-Tropical Storm Report". Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- Halbach (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Advisory Number 10". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- Ladar (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Advisory Number 13". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- Associated Press (2004). "Weakened Gaston to bring North Carolina wind, rain". Archived from the original on October 25, 2004. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "Event report for Tropical Storm Gaston (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "Event report for Tropical Storm Gaston". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- National Weather Service, Raleigh NC (2004). "Hurricane Gaston Event Report". National Weather Service. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- The Associated Press. "Gaston Recap". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "North Carolina event report for Tropical Depression Gaston". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "North Carolina event report for Tropical Depression Gaston (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "North Carolina event report for Tropical Depression Gaston (3)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "North Carolina event report for Tropical Depression Gaston (4)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- David Roth (2004). "Hurricane Gaston rainfall summary". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Event Report". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Robb Crocker and Matthew Philips (2004). "Back To Business". Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Civil War News (2004). "Winds And Rain Hit City Point & Richmond". Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Associated Press (2004). "Flooding devastates part of Richmond; Tropical Storm leaves at least 5 dead in Virginia".

- LISA A. BACON (September 1, 2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Kills Five in Virginia". New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Associated Press (2004). "Flooding devastates Richmond, Va.: Five people were killed, businesses destroyed from storm's deluge". Charleston Daily Mail.

- Storm Prediction Center (2004). "August 30, 2004 event reports". NOAA. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Event Report (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- National Climatic Data Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Gaston Event Report (3)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2004). "2004-Gaston". Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- "Where The Newspaper Stands". Daily Press. September 4, 2004. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- Storm 2004 Hurricane Season: Gaston Archived October 22, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ElBoghdady, Dina (September 28, 2004). "The Scam After the Storm?". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Gaston (2004). |